By Heiko Borchert

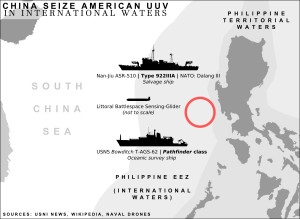

On 15 December 2016, China seized an Ocean Glider, an unmanned underwater vehicle (UUV), used by the U.S. Navy to conduct oceanographic tasks in international waters about 50-100 nautical miles northwest of the Subic Bay port on the Philippines. Available information suggests that the glider had been deployed from USNS Bowditch and was captured by Chinese sailors that came alongside the glider and grabbed it “despite the radioed protest from the Bowditch that it was U.S. property in international waters,” as the Guardian reported. The U.S. has “called upon China to return the UUV immediately.” On 17 December 2016 a spokesman of the Chinese Defense Ministry said China would return the UUV to the “United States in an appropriate manner.”

Initial legal assessments by U.S. scholars like James Kraska and Paul Pedrozo suggest the capture is violating the law of the sea, as the unmanned glider can be defined as a vessel in international maritime law that enjoys U.S. sovereign immunity. China, by contrast, justifies the capture with reference to its national security. According to Senior Colonel Zhao Xiaozhuo of the PLA Academy of Military Science, the glider “could have threatened the interests of China’s islands, or China’s ships and submarines. It must have damaged Chinese interest that caused the seizure.”

As this incident evolves and more information will become available, it might be useful to start thinking about some of the more long-term consequences of this UUV seizure. Building on a previous analysis of the impact on UUV in the Asia-Pacific region, I would like to suggest three observations for further consideration:

Unmanned Assets are Attractive Targets that Challenge Strategic Communication

This is not the first time an unmanned asset has been captured. Defense News reported that “an ‘unknown vessel’ grabbed another underwater vehicle operated by a U.S. ship near Vietnamese waters, but the vehicle was recovered.” In 2011, Iran seemed to have downed a RQ-170 Sentinel unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) by jamming its radar system in order to force the UAV to land in an area it was not supposed to land.

In line with these incidents, the most recent UUV capture reinforces the message that unmanned assets that have been designed with benign operating environments in mind and are attractive targets that can be easily captured or attacked. This is a prime challenge for strategic communications.

Seizing a U.S. UUV during the transition phase of the U.S. administration is a first rate headline grabbing media event, which might explain why it occurred now. It illustrates, as a Chinese scholar quoted by the South China Morning Post said, “the power of the Chinese army.” However, a UUV that hovers at the surface can be more or less easily captured. This time no one shot a picture of the “catch”, but this could be different next time. This might prompt a rethink of the media-related cost-benefit analysis of deploying UUVs in hotspots, which leads to the second thought.

Ready to Catch and Ready to Lose?

Testing the U.S. response certainly was a motive in the UUV capture. As Michael S. Chase et. al. have shown, China closely follows the U.S. use of unmanned assets also in view of justifying its own action and developing its own policies and concepts. The incident underlined China’s growing self-confidence and readiness to seize UUVs. But what about the U.S.?

At first sight, the U.S. response was measured and adequate by prompting China to return the captured asset to comply with international law. ‘We play by the rules, you don’t’ – this was the U.S. message. Apart from the question, if you can deter someone who just broke the rule by reminding him not to do so, there is a more trenchant issue at play.

Unmanned systems are attractive because they are easy pickings, but the emphasis on the need to return the U.S. UUV could undermine this very key advantage. In this case the UUV is treated like a manned asset because the overall message is about norm compliance. However, if you want the other side to hand back a relatively low-cost glider, can you credibly convey the message you would be ready to lose a much more sophisticated Large Displacement UUV?

This is the policy question the new U.S. administration and other governments using unmanned assets will need to work on, because a similar incident could occur in the Arabian Sea, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Black Sea, or the Baltic Sea.

Catch Me If You Can: Thinking About More Nuanced Counter-Responses

Emerging powers have had enough time to study the use of unmanned assets in particular by the U.S. Their first line of defense focused around mimicking U.S. practice in order to catch up. The second line of defense evolves around counter-measures. The seizure of the U.S. glider clearly signals that UUVs need to be prepared to fend off counter-measures as well. Thus more nuanced responses will be needed.

First, more thought needs to be given to when and where to deploy UUV in a non-benign naval environment. The current incident clearly shows that the tactical and strategic benefits of UUVs can quickly turn into a strategic liability if other actors are not willing to back down on their own policy line.Second, this incident should accelerate the development of swarms of Extra Small UUV (XSUUV) that would be radically smaller than current gliders and more difficult to track and trace.

Third, the XSUUV swarm could also help deconflict the policy dilemma. XSUUVs would hardly qualify as vessels enjoying sovereign immunity. Other forms of countering XSUUV notwithstanding, the risk of losing them would be much lower, which could make it far less attractive to catch them.

Fourth, self-protection will become more important in particular for more sophisticated UUVs that execute different missions at the same time. However, solutions should keep the above policy dilemma in mind: if measures to protect the UUV from adversarial interference become too demanding and thus might outstrip the benefits of using UUV, something is probably wrong about the operational concept guiding the respective UUV use.

Dr Heiko Borchert runs Borchert Consulting & Research AG, a strategic affairs consultancy.

Featured Image: A Littoral Battlespace Sensing, LBS, glider (U.S. Navy)