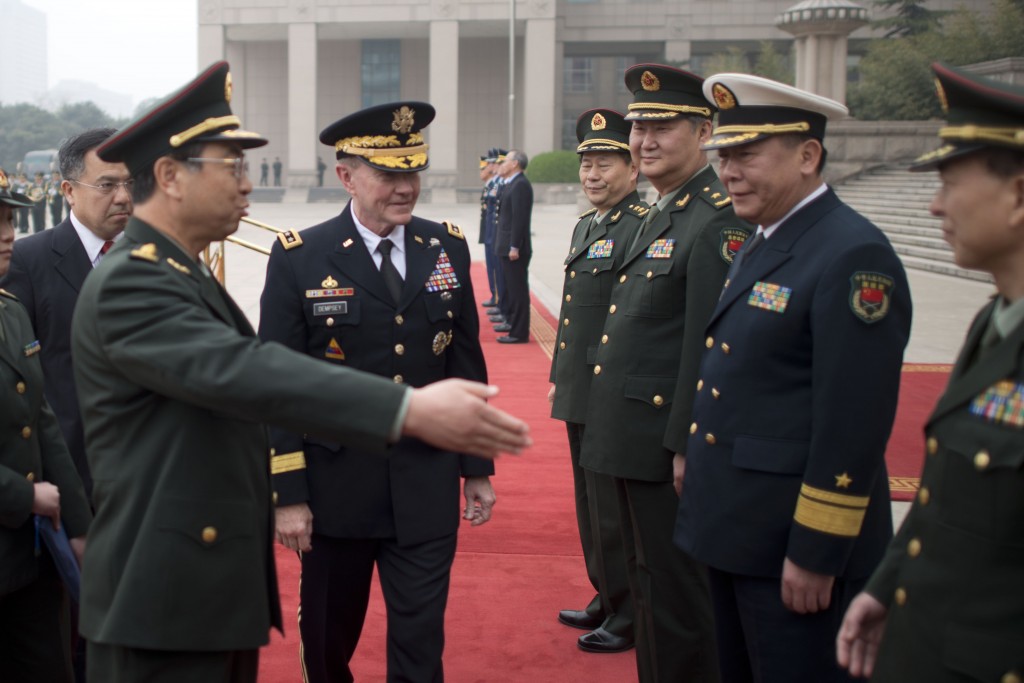

Exhibit 1: Sendoff Ceremony for Danzhou’s Flotilla.

By Andrew S. Erickson and Conor M. Kennedy

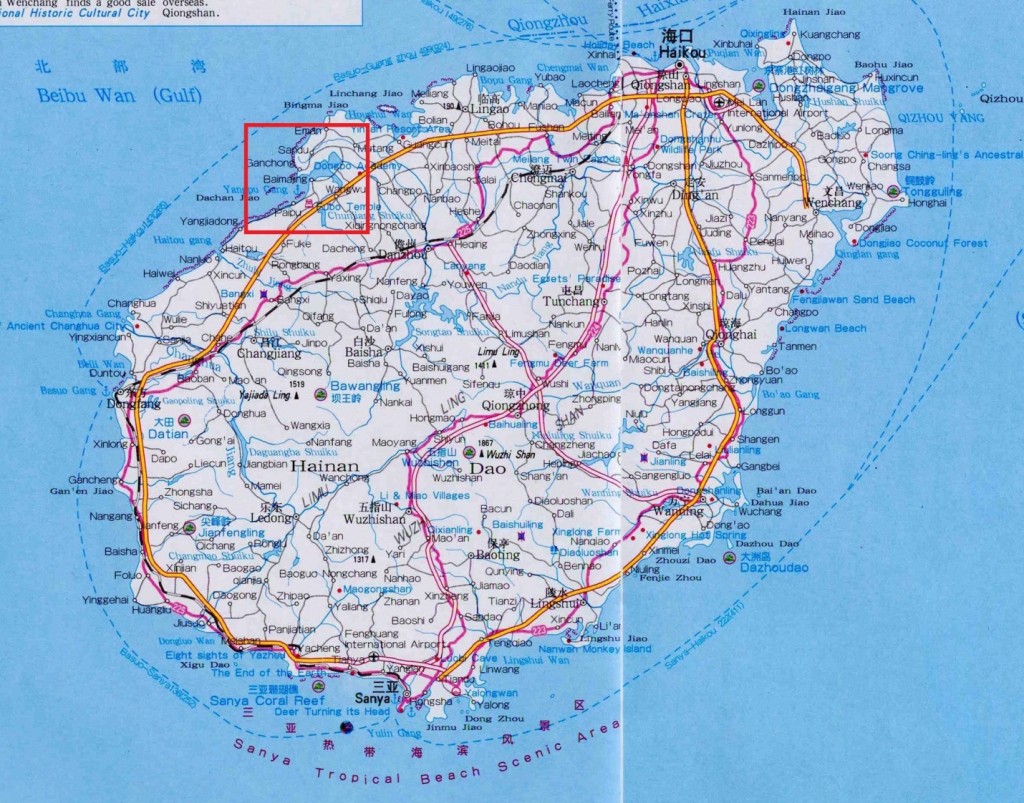

This is the second article in a five-part series exploring Hainan Province’s maritime militia, an important but little-understood player in the South China Sea and participant in its ongoing disputes. Our first article covered the maritime militia of Sanya City on Hainan Island’s southern coast, China’s closest naval and geo-cultural analogue to Honolulu. Now we direct our focus to Hainan’s northwestern shore, home to Baimajing (白马井, lit. “White Horse Well”) Fishing Port in Danzhou Bay. If Sanya and its Fugang Fisheries Co., Ltd. can be considered a wellspring of recent frontline activities by irregular Chinese forces in the South China Sea, Danzhou and its succession of fisheries companies—the current incarnation being Hainan Provincial Marine Fishing Industry Group (海南省海洋渔业集团)—may be regarded as some of the pioneers of military applications for Chinese maritime militia use in recent decades. Examining Danzhou’s forces in detail thus offers a comprehensive window into the origins, contributions, and ongoing development of China’s maritime militia to help elucidate these irregular actors.

China’s maritime militia forces are responsible for both peacetime and wartime roles. Most recently, their peacetime mission has focused on the protection of China’s maritime rights and interests. Maritime militia charged with the peacetime mission of “rights protection” (维权) could engage in the simple flooding of disputed waters with Chinese vessels, resisting foreign vessels’ attempts to drive them away. During wartime, maritime militia detachments might provide logistic support to active duty forces, or even lay sea mines themselves.

In the decades following the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the maritime militia served important coastal patrol functions, providing regular sea monitoring during their normal operations, and preventing Nationalist agents from infiltrating the mainland. While recent examples of irregular forces such as the Sanya maritime militia performing rights protection actions are available for observers to study, the fortunate absence of any recent maritime conflict leaves their potential use during any actual future combat less clear. Open sources can nevertheless help elucidate this important yet understudied issue. The maritime militia’s current training program for wartime missions is well-documented. Further insights may be gleaned by studying its actions during a previous conflict and in particular during a naval battle, which should serve as useful sources of insight into how the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy (PLAN) may undertake any future potential coordination with the maritime militia. This conflict is the PLA Navy’s employment of the South China Sea Fisheries Company’s maritime militia during the 1974 contest between China and South Vietnam (hereafter, “Vietnam”) over the Paracels.

Although the mission roles of the maritime militia have evolved since 1974, they still retain many wartime functions deemed important by Chinese leaders. Considering that both the Paracel and Spratly archipelagoes are widely dispersed; and that some features are occupied by China’s weaker neighbors, with at least one maintaining a military alliance with Washington; any employment of the maritime militia in a limited Spratly conflagration could potentially resemble the 1974 conflict in important respects. Maritime militia activities could conceivably form a tripwire for confrontation that Chinese leaders might believe could confound American intervention, especially if the costs of intervening promised to damage U.S.-China relations significantly.

Danzhou Bay’s Baimajing Fishing Port holds a unique place in China’s recent history as the PLA’s first landing site during the Hainan Island Campaign (海南岛战役) in 1950. There, on 5 March, the PLA made the first of a series of landings that collectively allowed it to link up with the local guerilla resistance to achieve an overwhelming victory over Nationalist forces by 1 May and to expel surviving enemy soldiers completely from the island. Subsequently, Baimajing became home to the South China Sea Fisheries Company (南海水产公司). Established in Guangzhou, in neighboring Guangdong Province, it became one of the metropolis’s largest fishing companies before moving to Baimajing in 1958. In a sign of the interconnected nature of such enterprises, the South China Sea Fisheries Company still maintained operations in Guangzhou.

Two trawlers employed by the South China Sea Fisheries Company served in a variety of supporting roles for the PLA Navy during the January 1974 Battle of the Paracel Islands (西沙海战). From the outset, the militia’s presence agitated the Vietnamese naval forces, and served to steal the initiative from them. Vietnamese destroyer commanders were preoccupied with determining how to deal with these trawlers without resorting to armed force, affording the PLA Navy time to coordinate its own forces. The militia was tasked with monitoring the Vietnamese flotilla, and rescue and repair of a badly damaged PLA Navy mine sweeper. After the PLA Navy repelled the Vietnamese flotilla, the two trawlers provided transportation for 500 troops—two companies and an amphibious reconnaissance team from the Hainan military district—onto the remaining Vietnamese-occupied features. The Vietnamese hold-outs on the islands were quickly overwhelmed and surrendered. While small in scale, the important supporting role these irregular forces played during a period of PLA Navy weakness helped China secure ground crucial to supporting its current maritime strategy in the South China Sea.

In 1974, Vietnamese commanders were forced to choose between open conflict and a Chinese fait accompli. When confrontation began and PLA Navy assets became involved, Saigon reached out to its ally, Washington, for assistance. However, perceiving Sino-American rapprochement as more critical than the fate of a few features in the South China Sea, the United States did not come to the aid of the Vietnamese. Today, Second Thomas Shoal presents a similar potential flashpoint. There, Chinese maritime militia forces might seek to dislodge the few Philippine marines stationed on the Sierra Madre. With Mischief Reef—an established Chinese fishing outpost that has recently undergone large-scale reclamation and militarily-relevant infrastructure development—only 15 miles away, maritime militia vessels could be rapidly deployed to Second Thomas Shoal in greater numbers. The Paracels Battle began with the appearance of two Chinese trawlers in the waters around Robert Island, approximately 54 miles from the nearest harbor on Woody Island. Closer in proximity to Second Thomas Shoal, Mischief Reef provides an even more advantageous base of operations and supply for militia action than Woody Island did, should conflict occur.

Building on Glorious History: “Catching Government Fish and Casting Nets of Sovereignty”

Economic and institutional structures, which form the basis and strength of the maritime militia’s organization, quite literally underpin Danzhou’s maritime militia. As a state-owned enterprise, the South China Sea Fisheries Company and its successor organizations have been a major presence, both in Baimajing fishing port and province-wide. Having operated the harbor’s fishing pier for over five decades under various names, currently Hainan Provincial Marine Fishing Industry Group, it is now one of Hainan’s largest marine fisheries companies.

That said, the company’s close ties with provincial and local governments, as well as China’s broader political and economic development, have imposed a complex organizational history. In 1981, the company divided organizationally into separate entities, with personnel, and vessels apportioned between Hainan Island and Guangzhou; to the best of our knowledge, these geographic entities have subsequently enjoyed commercial ties, but have never re-merged organizationally. In 1988, Hainan Island and China’s wide-ranging South China Sea claims were separated from their previous administrative position within Guangdong Province to become a province in their own right. The Hainan branch of the South China Sea Fisheries Company changed its name to Hainan Provincial Marine Fishery Corporation (海南省海洋渔业总公司). Inspired by the designation of Hainan as a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) at the time of provincial formation in 1988, and its subsequent economic boom, the company began investing heavily in real estate. In 1992, Hainan’s real estate bubble burst, sending the corporation into severe debt.

Today’s success is built on yesterday’s reform. Heavily indebted, and entering bankruptcy, Hainan Provincial Marine Fishery Corporation suspended operations in 2003. In 2006, however, Deputy Provincial Governor Wu Changyuan (吴昌元) held special meetings to address the company’s collapse. A new company, the South China Sea Modern Fishery Company (南海现代渔业公司), was established. Several years of restructuring returned the enterprise to profitability.

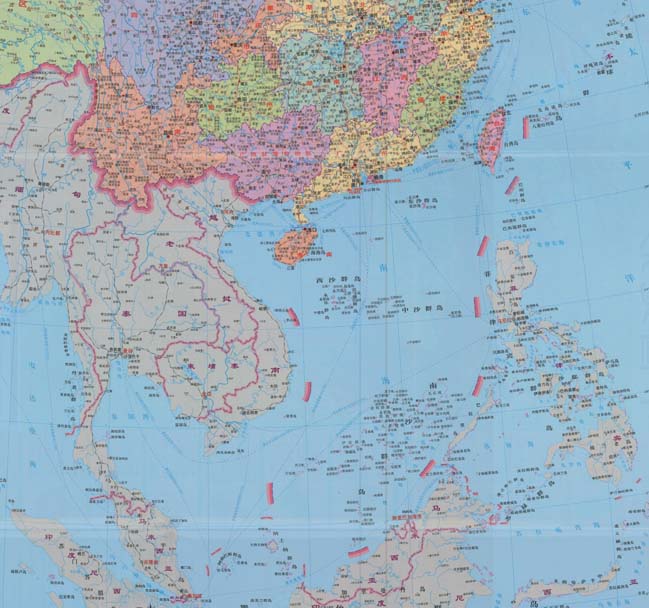

In 2009, Danzhou’s fishing enterprise entered its latest incarnation as Hainan Provincial Marine Fishing Industry Group. It has re-established its presence across Hainan, revamping existing subsidiaries in places like Baimajing and Tanmen Village, as well as initiating development projects elsewhere, such as in Ledong’s Lingtou Port. This new company is intended to serve as a leading platform for government investment into Hainan’s marine fishing industry and fishing harbor development. The company and provincial government have major plans for fisheries development in the South China Sea, starting with fishing harbor infrastructure projects and the organization of multiple fishing flotillas to operate in the Spratlys. The Hainan provincial and Danzhou municipal governments together have reportedly invested over 200 million RMB ($30.4 million) in the construction of Baimajing’s harbor, including expanded piers and deeper berths to facilitate large-scale aquatic product processing. Recent municipal committee meetings reaffirmed the government’s support for Baimajing’s harbor development. The aforementioned flotilla operations were introduced in our last piece analyzing Sanya’s maritime militia, foremost among them the Fugang Fisheries Co. Ltd., also among the province’s five leading fisheries enterprises. All fishing vessels seeking to operate in the Spratlys must join these group formations, according to article ten of China’s “Nansha Fishery Regulations.” The regulations stipulate rules for fishing vessels operating south of 12-degrees North latitude in the South China Sea, including requirements for each formation to designate and operate a command and communications vessel for reporting to shore-based stations. This could be a single trawler, or a larger command and supply ship supervising the other trawlers.

The South China Sea Modern Fisheries Group’s ties with the military did not begin with the 1974 action in the Paracels. As early as 1961, its predecessor, the South China Sea Fisheries Company, established a People’s Armed Forces Department (PAFD) to be managed directly by the Hainan military district. In 1967, during the Cultural Revolution, the South China Sea Fisheries Company came under direct management by the military and received 80 sailors from the PLA Navy. It officially established a militia headquarters in 1975, possibly linked to its success in the Paracels Battle as well as the national political campaigns of the time.

Called Hainan Provincial Marine Fishing Industry Group today, the company has not forgotten its glorious past. Its website proudly recounts its predecessor organization’s participation in the Paracels Battle, and proclaims that it will carry out the nation’s policy of “protecting sovereignty” and “emphasizing presence” in the South China Sea through its current focus on fishing port development and dispatching supply ships (capable of supporting trawlers from multiple localities) to fishing grounds in the Spratlys. It further states: “Grasp the principles of ‘being both military and commercial, both soldiers and civilians, combining war and peacetime and civilian-military dual use’ to organize a Spratly fisheries supply fleet. [They will] organize and drive the fishermen masses to go to the Spratlys on a large scale and open up new fishing grounds, ‘catching government fish and casting nets of sovereignty’ to display sovereignty and let the Chinese flag wave over waters in the Spratlys” (抓紧以 “亦军亦企、亦兵亦民、平战结合、军民两用” 的原则组建南沙渔业生产补给船队,组织和带动群众渔民大规模地赴南沙开辟新渔场,“打政治鱼、撒主权网”,让五星红旗飘扬在南沙海域,彰显主权).

One news report states that the company plans to establish 20-30 of the aforementioned “Nansha Fishery Regulations”-mandated flotillas, each with a large command and supply ship leading 30 fishing vessels. The article elaborates that these supply ships will “try out militia reserve structures” (实习民兵预备役编制). Together with the local government, the company is focusing on building the necessary infrastructure—deeper harbors, piers, ice factories, etc.—to support these operations. Danzhou’s Baimajing and Sanya’s Yazhou Fishing Port are both officially ranked as “core fishing ports” (中心渔港). China’s fishing ports are divided among four tiers based on their size and capacity; core fishing ports receive national-level investment and guidance. Based on the activities of Sanya’s Fugang Fisheries Company, it can be inferred that the South China Sea Modern Fisheries Group, with its similarly close government ties, may assume future maritime militia responsibilities.

Danzhou’s flotilla made its inaugural “rights protection” expedition to the Spratlys, departing Baimajing’s piers in May 2013. Thirty 100-plus-ton trawlers led by a 4,000-ton command and supply ship and a 1,500-ton cargo ship made a 40-day trip to the Spratly fishing grounds. Interestingly, the two ships leading them—bearing hull numbers Qiong Sanya F8138 and F8198—belong to a Sanya-based company. This indicates a degree of cooperation between areas to mount these fishing expeditions, potentially reflecting broader government guidance. En route to the Spratlys, the flotilla experienced a nighttime encounter with two law enforcement vessels of unknown origin, likely Vietnamese, but were able to proceed without incident.

While the Danzhou excursion was modeled expressly on the formation described above, other entrepreneurs have also promoted ideas to boost local fishing fleets’ ability to operate in the Spratlys, centered on the same concept of using a mobile base of operations to sustain extended fishing expeditions. The Fucun Collective (福村合作社), located in Baimajing township, submitted proposals to the provincial government to help it expand its current fleet of fishing vessels, and to begin a major overhaul of its operations within five years. To facilitate large-scale fishery operations, Fucun requested government assistance for the purchase of a 10,000-ton mother ship and seven 1,000-ton subordinate shuttling supply ships. The mother ship would conceivably function as a command center, floating base, and transfer dock to coordinate, supply, and process the catches of, numerous smaller fishing boats. By contrast, much of Hainan’s fishing fleet is still composed of small, wooden “hook industry” (钓业) vessels incapable of reaching the Spratlys. Relying on such a large platform and accompanying supply ships could potentially allow numerous smaller craft to operate more permanently in the Spratlys, unlike the temporary expeditions of flotillas composed of larger trawlers. The Hainan Oceanic and Fisheries Department’s conditional response to the proposal did not deny assistance outright, but rather underscored and enforced its growth control policies, whereby collectives must first dispose of old, obsolete vessels before building new hulls. This example suggests the extent of local initiatives to increase presence in the Spratlys, as well as what the provincial government deems acceptable measures.

As China attempts to resuscitate its depleted coastal fisheries and becomes increasing reliant on distant water fishing, creative entrepreneurs like those in Fucun are proposing projects that would facilitate the movement of its more numerous smaller-sized fishing trawlers to the Spratlys in search of better fishing grounds. Although this could conceivably alleviate the strain on coastal fisheries, it runs counter to the larger national effort to modernize Chinese fishing fleets overall, and to embed reliable maritime militia capabilities within some of them specifically. Instead of fostering continued reliance on smaller, wooden fishing vessels that cannot sustain operations far from shore, the government prefers to support larger tonnage, steel-hulled vessels that are more capable of distant water fishing—and may effectively double as sovereignty support tools in the South China Sea. Modern fishing vessels can endure rougher seas, collisions with foreign vessels, and employ more advanced equipment (communications), thereby granting maritime militia on such vessels greater capacity to serve in a variety of mission roles. While attempting to manipulate or parry policies from above to better suit one’s local or even personal interest is a time-honored technique vis-à-vis China’s gargantuan bureaucracy, sustained government prioritization of maritime militia development to serve state sovereignty and security interests at sea appears to be winning the day.

In further evidence of sustained, systematic support for maritime militia building, numerous articles on the maritime militia by local military officials urge local governments to establish a legally-based support system to protect the militia and supply much needed economic incentives for militia units to actively fulfill their duties. He Zhixiang, head of the Guangdong Military Region mobilization department, which oversees Hainan’s mobilization work, penned an article in early 2015 exhorting governments to purchase insurance and provide financial assistance according to “Naval Personnel At-Sea Standards” (海军海员出海标准) for fishermen recruited into the maritime militia. The Nansha Fishing Regulations provide rules for fuel subsidies for fishing fleets operating in the Spratlys, as well as compensation if they are harmed by foreign vessels. There are also benefits specific to the maritime militia, such as additional compensation for wages forgone through participation in training or missions. Militia members are eligible to receive superior insurance subsidies, according to a Hainan Daily news article. It states that Hainan’s provincial Department of Human Resources and Social Security plans to include fishermen in the work-related injury insurance system and provides greater insurance subsidies for the maritime militia. Danzhou, for instance, provides its militia with a “disability pension” of 56,400 RMB ($8,636) a year if they become disabled in the line of duty—a sum that might well be considered significant in a fishing village with a relatively low cost of living.

This figure is not much less than the pensions to which People’s Police (人民警察), regular municipal law enforcement) or state personnel/functionaries (国家机关工作人) are entitled if similarly disabled in the course of their work. This is part of a broader pattern of implementation of national-level law entitled “Measures for the Administration of Disability Pensions” (伤残抚恤管理办法), whereby reservists, militia, and migrant workers harmed in war, field exercises, training, or other service duties are categorized together and entitled to equivalent disability pensions. Ongoing PLA legal reforms may further shape these and other laws and regulations concerning China’s maritime militia. The leaders of Danzhou, and many other localities, appear prepared to spend considerable time and effort finding the right mix of economic incentives, aggrandizing propaganda, and patriotism to mobilize the maritime militia under their jurisdiction.

The Gray Zone

Hainan’s maritime militia are assigned an important role in protecting China’s sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea, but they could also be of service in a variety of roles that fall somewhere between peace and war. Fishing flotilla formations deployed with increasing frequency in the South China Sea greatly increase the organizational efficiency of the maritime militia units that sometimes participate in their operations. For China’s maritime law enforcement and naval forces, these formations can increase their ability to monitor large numbers of vessels, since the command and supply ships provide dedicated on-site management and communications with the fishing fleet. Furthermore, even if only the supply ships had militia organizations on-board, those militia members could conceivably requisition some of the flotilla’s trawlers and mobilize them for specific operations. On scene requisition could enable reconnaissance or rights protection actions without delay, allowing for an immediate response to foreign incursions into Chinese-claimed waters. Maritime militia participating in a flotilla operation in the Spratlys could also provide an excellent source of reserve manpower and vessels for assisting PLA Navy operations farther away from the support of their bases on China’s southern coast.

In recent years, like many other Hainan province localities, Danzhou has increased emphasis on maritime militia building. Danzhou’s leadership regularly issues statements to support strengthening the maritime militia. One example is that of former PAFD head Fu Huaming, who included maritime militia building as an important focus when giving orders to the heads of Danzhou’s grassroots PAFDs in 2011. To gain the military’s support for Danzhou’s development, Fu joined a delegation of Danzhou officials to the provincial military district headquarters in early 2014. Zhang Qi, formerly Party Secretary of Danzhou and now Party Secretary of maritime militia powerhouse Sanya City, reportedly included in his remarks during the visit the full extent of Danzhou’s maritime militia building efforts. This suggests that the performance of local officials in militia building, already one of their responsibilities, helps to some degree in currying favor with local military officials. PLA support could bring greater benefits to Danzhou’s development projects—especially since, located on Hainan’s relatively arid, isolated west coast, they receive far less tourism than popular destinations like Sanya City. Perhaps in part thanks to his militia-building efforts, PAFD head Fu Huaming was subsequently promoted to Deputy Chief of Staff of the Hainan provincial military district. As the political tide of the “Maritime Power” development strategy officially promulgated by paramount leader Xi Jinping himself swells, it appears that maritime militia building may be an important link in the machinations of local political and military officials looking to rise up the provincial ranks.

Amid these broader trends, Danzhou’s new leadership has taken up the mantle of local militia building. During a PAFD transfer-of-leadership meeting in late 2014, in which Danzhou Party Secretary Yan Chaojun was appointed first secretary of the PAFD, Yan extolled Danzhou’s location on the “frontier” (前沿) of the South China Sea. He called for “strengthening the national defense reserve forces, with maritime militia building of particular importance” (加强国防后备力量建设尤其是海上民兵建设极其重要). In early 2015, Danzhou’s leadership held a meeting on militia reserve work, declaring that the city would strengthen the maritime militia and land-based emergency response militia in “preparation for military struggle in the South China Sea” (南海军事斗争准备). The support of both local party and military leaders will determine Danzhou’s maritime militia growth and effectiveness, as they share a direct responsibility for militia building within their jurisdiction.

The Central Government has signaled the importance of maritime militia building to local governments. In January 2014, the State National Defense Mobilization Committee held the “Maritime Mobilization – 1312” symposium in Hainan’s Qionghai City to discuss the province’s maritime militia. During this event, maritime militia rights protection and warfighting support exercises were held at Tanmen Village with Danzhou’s maritime militia detachment featured prominently. The exercises extended from October 2013 to January 2014. Former Danzhou Deputy Party Secretary Wang Qiongzhu convened a meeting in Danzhou to review the results of the symposium and their maritime militia’s participation. Wang Qiongzhu declared maritime militia building to be a part of national maritime strategy and “an act of the state.” With plans to build three new maritime militia units, Danzhou has completed construction of its first unit in Baimajing. It has been over four decades since trawlers from Baimajing were dispatched to the Paracels, where they supported China’s victory against the Vietnamese. Today, we are witnessing a maritime militia revival, with the avowed purpose of both protecting China’s rights and supporting active duty forces in military struggle.

In probing potential wartime applications of China’s maritime militia, it is important to consider that China’s militia is an official component of its armed forces. Militiamen are not independent citizens independently organizing themselves into militia, or self-directed fishermen driven extemporaneously by personal patriotic fervor. Rather, in today’s China, local government and PLA organs are responsible for militia building, and will mobilize their local militia in times of emergency, as directed by higher authorities in a process involving the PLA chain of command. The idea of the militia often evokes old Maoist ideas about People’s War, an approach to conflict that utilizes Chinese traditional advantages in terrain, population, and fighting stratagems. China’s military still embraces the concept, and has adjusted its content to suit changes in modern warfighting. Beijing included the concept of “Maritime People’s War” (海上人民战争) in its 2006 Defense White Paper, stating that its navy was “exploring the strategy and tactics of maritime people’s war.” Ge Yonghong, head of the Nanjing Military Region’s mobilization department, formulated the military actions encompassed by Maritime People’s War, or the related concept of “People’s War at Sea” (海上的人民战争), most of which assign important roles to the militia. While official Chinese sources typically do not describe the Paracels Battle explicitly as an example of Maritime People’s War, the clear use of classic People’s War tactics in the battle itself may further inform our understanding of possible Chinese employment of maritime militia in a potential future crisis or conflict in the South China Sea. Specifically, the combined employment of the main forces (the PLA Navy) with mobilized local civilian forces (the militia) using unconventional tactics to overcome a superior enemy force exemplifies the People’s War approach. Despite the marked differences in China’s armed forces between 1974 and the present, its continued emphasis on the maritime militia suggests the possibility of a repeat scenario today vis-à-vis disputed flash points such as the Spratly Islands.

Today Danzhou’s maritime militia forces and the fishing organizations in which they are based are being revitalized and developed further, even as they enjoy increasing interconnections with counterparts in Sanya and Tanmen. The last is home to another major maritime militia, the subject of the next article in our series on the leading maritime militias of Hainan Province. This third, forthcoming, article will explore the maritime militia of Tanmen Village, north of Bo’ao on Hainan’s east coast. It will build on our previous scholarship in this area, which traces a Tanmen maritime militia company’s designation as a “model militia work unit” (民兵工作模范单位), “militia advanced grassroots work unit” (民兵基层建设先进单位), and “advanced border and coastal work unit” (边海防工作先进单位) following an official visit to Tanmen’s fishing harbor and maritime militia by Xi Jinping in April 2013. Different levels of PLA command have all recognized the Tanmen maritime militia for their perseverance, bravery, and patriotism in protecting China’s claimed sovereignty in the South China Sea. In keeping with general incentives for Chinese officials to learn from Party-and-government-sanctioned examples, a delegation including Sansha City’s Mayor and Party Secretary Xiao Jie has visited Tanmen, and then-Danzhou Party Secretary Zhang Qi led a delegation there in November 2013. Beyond the basics of militia development and mobilization, what might these officials be learning about and be planning for their own forces to prepare for? We have traced direct Tanmen militia involvement in international controversies and incidents, including “island construction” in the Spratlys and the 2012 Scarborough Shoal Standoff.

Stay tuned for further analysis of China’s leading irregular forces at sea!

Dr. Andrew S. Erickson is a Professor of Strategy in, and a core founding member of, the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. He serves on the Naval War College Review’s Editorial Board. He is an Associate in Research at Harvard University’s John King Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies and an expert contributor to the Wall Street Journal’s China Real Time Report. In 2013, while deployed in the Pacific as a Regional Security Education Program scholar aboard USS Nimitz, he delivered twenty-five hours of presentations. Erickson is the author of Chinese Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile Development (Jamestown Foundation, 2013). He received his Ph.D. from Princeton University. Erickson blogs at www.andrewerickson.com and www.chinasignpost.com. The views expressed here are Erickson’s alone and do not represent the policies or estimates of the U.S. Navy or any other organization of the U.S. government.

Conor Kennedy is a research assistant in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the US Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. He received his MA at the Johns Hopkins University – Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies.