By Andreas Kuersten

Shielded by a significant expanse of sea ice, the Arctic Ocean has historically had limited naval strategic relevance outside of submarine and early warning operations. But the process of climate change is increasingly melting away this covering and laying bare previously inaccessible northern waters. As a result, and in concert with the region’s vast natural resource endowments and potential shipping lanes, one of the world’s five oceans and adjacent marine areas are slowly opening to human maritime activity – both in terms of state and private actors. As the military branch responsible for fielding forces “capable of winning wars, deterring aggression and maintaining freedom of the seas,” the United States Navy has understandably turned its attention northward.

In planning for the Arctic Ocean’s opening and its ensuing responsibilities in the region, the Navy researched and published the Arctic Roadmap: 2014-2030. The report lays out how the service views the high north as a theater for operations and its priorities in the area in the near- (2014-2020), mid- (2020-2030), and long-terms (2030-beyond).

The Arctic Naval Strategic Environment

As outlined at the beginning of the Roadmap, the Navy expects the Arctic “to remain a low threat security environment where nations resolve differences peacefully.” It sees its role as mostly a supporter of U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) operations and responder to search-and-rescue and disaster situations. However, the presence of vast resource endowments and territorial disagreements “contributes to a possibility of localized episodes of friction in the Arctic Region, despite the peaceful intentions of the Arctic nations.”

For the most part, this assessment appears accurate. The Arctic has consistently remained an area of peaceful interaction despite periodic disagreements, and its harsh environment minimizes conflict potential. But the region also presents a completely unique geopolitical and military situation for the Navy. As Arctic sea ice melts, the Navy will find itself engaging a theater where it is not the most capable force for the first time in recent history. Russia’s Northern Fleet, designated in 1937, has been based and operating in the Arctic for nearly 80 years. Russian naval and support capabilities in the high north surpass those of the Navy: currently, they possess the only fleet of nuclear powered icebreakers and extensive naval bases.

Direct comparisons with Russia, however, are not very telling in terms of what the Navy’s Arctic priorities should be. Russian interests in the Arctic have always been far greater than those of the U.S. As such, the Roadmap is right to avoid any language seeking American naval predominance in the region, or comparisons to the northern capacities of others. But given Russia’s recent provocative actions in Ukraine and elsewhere, and the fact that the Roadmap was published before these commenced, the Navy would be right to incorporate awareness of Russian activities and capabilities into future Arctic policy publications.

The Navy’s Arctic Capabilities

Turning to the more technical issue of actual Arctic capabilities, the Roadmap presents the region as a unique operational environment. It astutely notes that “Navy functions in the Arctic Region are not different from those in other maritime regions; however, the Arctic Region environment makes the execution of many of these functions much more challenging.” This observation was born out in the Fleet Arctic Operations Game naval exercise of 2011. Unfortunately, so was the reality that the Navy is currently ill equipped to operate in the high north. A report from the U.S. Naval War College on this exercise noted the following:

The U.S. Navy is inadequately prepared to conduct sustained maritime operations in the Arctic region. This assertion is due to the poor reliability of current capabilities as well as the need to develop new partnerships, ice capable platforms, infrastructure, satellite communications and training. Efforts to strengthen relationships and access to specialized capabilities and information should be prioritized.

The Roadmap seeks to take each of these failings into account, though it does so to varying degrees of prudence. It presents the need for strong cooperation and partnership with foreign states, the USCG, and other government agencies. Such interactions are aimed at helping to manage shared Arctic spaces, engage in multilateral training and operations, and develop Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) for the region.

The Roadmap puts a heavy emphasis on the advancement of MDA and logistics capabilities in the Arctic, and these foci are well warranted. The principal restrictive variables in Arctic operations are severe and erratic weather, sea ice, poorly developed nautical charts, remoteness, and the absence of support infrastructure. Tackling these issues begins with extensive data gathering and MDA development. In this regard, the Roadmap asserts that partnerships with government agencies responsible for meteorology and geography – such as the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – are crucial for helping “the Navy better predict ice conditions, shifting navigable waterways, and weather patterns to aid in safe navigation and operations at sea.” A force with a robust understanding of a harsh environment has a significant advantage in any undertaking or confrontation therein.

Arctic MDA will, in turn, aid in the maintenance of critical logistical support for naval assets deployed in remote northern theaters and the alleviation of infrastructure failings. The distribution of fuel and other resources, along with the conservation of these assets, are important considerations in Arctic operations and ones the Roadmap shrewdly highlights.

Beyond MDA and logistics, the Roadmap puts an emphasis on Arctic training and exercises. These are often conducted with other countries and military branches and are touted to “improve knowledge of the Region and provide a positive foundation for future missions.” While this is certainly true, training can only go so far when a force lacks the requisite equipment for operating in a region, and this is the Roadmap’s main problem.

The Naval War College’s assessment of the Navy’s Fleet Arctic Operation Game, noted above, serves to illuminate the branch’s deficiency in terms of material capacity when it comes to the Arctic. In addressing its equipment needs for northern operations, the Navy’s Roadmap is lacking. Rather than stating the need to procure necessary equipment, it simply “directs review and identifications of requirements for improvements to platforms, sensors, and weapons systems.”

For years, the needs of the Navy in terms of Arctic acquisitions and refitting have been extensively researched and presented. Many individuals and organizations have laid out the various basic purchases and upgrades necessary for effective Arctic naval action. Moreover, as reported by the website DoD Buzz through interviews with top Navy Officers, the branch is well aware of its needs and has undertaken numerous research and development projects to address them. Ice-strengthened hulls, topside icing prevention and management, surveillance and reconnaissance sensor establishment and maintenance, and network systems adaptation to northern conditions are all clear areas of need with available remedies.

Training and operating within equipment limitations enhances effectiveness, but being properly outfitted allows for substantially more freedom of action and strategy, as well as for the more likely attainment of superiority in any future confrontation.

Even though the Navy is currently experiencing a time of relative budget constraint and massive asset redistribution – namely to the region of East and Southeast Asia – a policy roadmap encompassing the next several decades must make Arctic-directed equipment procurement an expressed priority. These sorts of undertakings require a good deal of lead-time, and continuing to tread water by solely emphasizing need assessment over need fulfillment is a recipe for future shortfalls in necessary capabilities.

In addition to equipment, the Navy is also lacking in terms of Arctic infrastructure. Aside from Thule Air Base in Western Greenland, American deepwater ports are non-existent above the Arctic Circle. The Navy has utilized temporary ice bases in the past for submarine exercises – the most recent being Camp Nautilus north of Prudhoe Bay in 2014 – but to support the necessity of an increasing naval presence in the next several decades a permanent base and deepwater ports will eventually be needed.

These, however, are incredibly costly undertakings, both in terms of money and capital as well as force deployment to occupy such facilities. The absence of any clear intent to look into permanent presence possibilities, or commit to equipment procurements, evinces the Navy’s desire to hedge its commitments to a remote and relatively minor area in the face of important responsibilities elsewhere. While this is certainly prudent, such policies could become problematic if they result in the inconsequential development of Arctic capabilities over the period the Roadmap encompasses.

The Navy’s Near-, Mid-, and Long-Term Arctic Assessments

The Navy’s concluding presentation on its ambitions over the timeline of the Roadmap lends credence to concerns over its intent to meaningfully prepare for future Arctic obligations.

Within the near-term (2014-2020), the Navy plans to have a limited Arctic presence, “primarily through undersea and air assets.” Surface operations will only take place in open water conditions. More broadly, the Navy states that it aims to “increase the number of personnel trained in Arctic operations,” maintain ongoing exercises, “focus on areas where it provides unique capabilities,” “leverage…partners to fill identified gaps,” and “emphasize low cost, long-lead time activities to match capability and capacity to future demands.” From this information, it appears that the Navy has minimal Arctic ambition in the near-term and is content to expand very little on its current capacities.

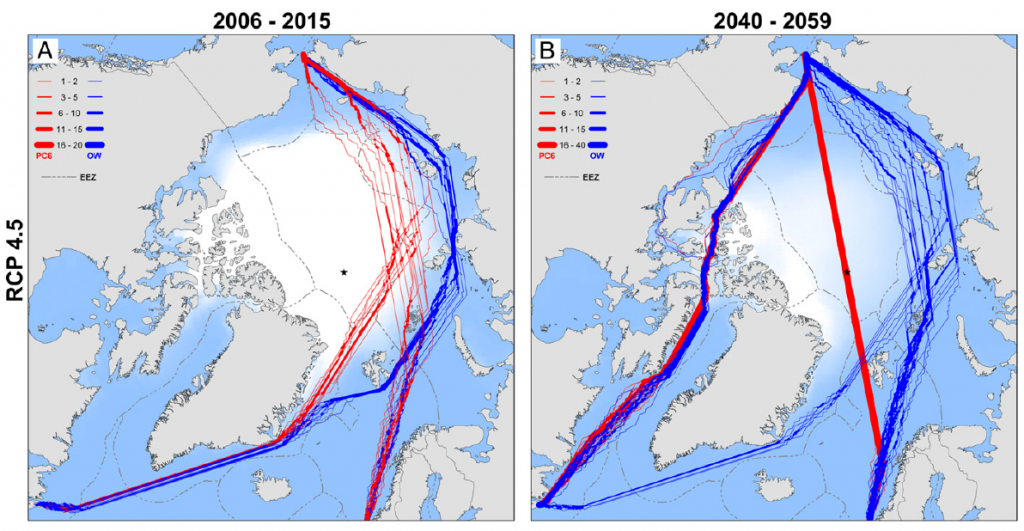

In the mid-term (2020-2030), the Navy predicts that it “will have the necessary training and personnel to respond to contingencies and emergencies affecting national security.” Its “surface vessels will operate in the expanding open water areas” and the Navy “will work to mitigate the gaps and seams and transition…from a capability to provide periodic presence to a capability to operate deliberately for sustained periods when needed.” Although this language may be interpreted to push for accelerating Arctic initiatives in the mid-term, it actually simply shows the Navy moving at the speed of climate change. Surface-wise, it will expand into the high north wherever the melting ice allows, but no real impetus is noted to engage the region outside of those areas that become like other environments in which the Navy already operates. Furthermore, there is not even an ambiguous expression as to how the Navy plans to facilitate “deliberate and sustained” Arctic operations.

In the far-term (2030-beyond), the Roadmap asserts that the “Navy will be capable of supporting sustained operations in the Arctic Region as needed to meet national policy guidance” and “will enable naval forces to operate forward.” Once again, however, no clear avenue, let alone a vague one, is presented through which these capabilities will be developed. Consequential investment in region-adapted equipment and infrastructure are needed before the Navy can meaningfully operate in a forward capacity in the Arctic. Unfortunately, as noted throughout this analysis, there is scant mention of any such commitment.

Conclusion

The Roadmap ultimately shows the Navy having a keen understanding of the capacities it must develop to be a truly Arctic-capable force, but also evinces an organization weary of any real commitment to a region currently possessing little national security importance. As the Navy puts it in the report’s final sentence: “The key will be to balance potential investments with other Service priorities.” The Roadmap, however, currently shows that balance tipping away from any substantial Arctic engagement. Hopefully the Navy’s fiscal apprehension will not hamstring its ability to operate in a future Arctic environment requiring its capable presence and leadership.

Andreas Kuersten is a lawyer working in international law who has previously held positions with NOAA and the U.S. Navy and Air Force JAG Corps.