French and Chinese light icebreakers attempted to close the distance between open water and the beset ship but could not get sufficiently close to break her out. Even the United States Coast Guard’s Polar Star was diverted to assist. The decision was then made to fly a helicopter from the Chinese ship Xue Long to repatriate the hapless high paying passengers and “science party”. A short time later, having never declared a distress, and knowing the ice conditions would change, the Master and crew steamed clear of the ice under their own power. In the end, the Australian government shelled out nearly $2m Australian in “rescue efforts”. Shortly after the Akademik Shokalskiy steamed clear of the ice, the Russians felt the situation had been so distorted as to its danger in the press that a formal statement was made at IMO making it clear that the Akademik Shokalskiy and her crew were well suited to the conditions, and at no time in danger and that the Master of the vessel did not declare distress.

French and Chinese light icebreakers attempted to close the distance between open water and the beset ship but could not get sufficiently close to break her out. Even the United States Coast Guard’s Polar Star was diverted to assist. The decision was then made to fly a helicopter from the Chinese ship Xue Long to repatriate the hapless high paying passengers and “science party”. A short time later, having never declared a distress, and knowing the ice conditions would change, the Master and crew steamed clear of the ice under their own power. In the end, the Australian government shelled out nearly $2m Australian in “rescue efforts”. Shortly after the Akademik Shokalskiy steamed clear of the ice, the Russians felt the situation had been so distorted as to its danger in the press that a formal statement was made at IMO making it clear that the Akademik Shokalskiy and her crew were well suited to the conditions, and at no time in danger and that the Master of the vessel did not declare distress.

The Polar Code

The playing out of the Akademik Shokalskiy incident became a backdrop for more frenzied efforts at IMO to finalize drafts and meet Secretary General Koji Sekimizu’s desire for a mandatory Polar Code as soon as practicable.

Throughout 2014, various committees, sub-committees and working groups struggled to finalize consensus-based drafts of a Polar Code; however, the Secretary General’s strict timetable demanding an adoption before 2017 unfortunately resulted in the gradual streamlining of the initial robust drafts. In order to meet the timelines set down, issues that were remotely contentious or not subject to almost total consensual agreement were watered down or omitted.

Many parties were disappointed to see a much weaker document evolve into what was finally approved by the Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) in November. Others leapt to declare a new age of safety and environmental protection for Antarctic and Arctic waters.

Come the end of 2014, the Polar Code was still some way from actualization. The entire Part II – Prevention of Pollution must still go through the Maritime Environmental Protection Committee adoption, then the Council must approve both parts submitted by MSC and MEPC. Still, given the SG’s direction, there will be a mandatory Polar Code in existence by the first of 2017; however, it will not be the powerful and robust direction it was originally envisioned to be.

As a result, many classification societies and flag states are already issuing “guidance” to close gaps that have been left by the leaner “more friendly” Polar Code. The Nautical Institute is moving forward with their plans to put in place an Ice Navigation Training and Certification Scheme to meet basic requirements of the human element chapter of the Polar Code with defined standards of training and certification.

Ice Conditions

Climatically, 2014 was more in line with 2013 as a heavier ice year overall in the Arctic this summer. This followed a particularly bad year in the North American East coast, where heavier ice trapped ships and lengthened the icebreaker support season into May. In the Arctic, conditions were much tougher than the low record years of the past decade that led up to the last two. No one with any real understanding of global climate change would suggest that 2013 and 2014 can be held as the “end of global warming”; however the variability experienced shows that it will not be easy-going for polar shipping in the near future and that ice conditions will continue to wax and wane.

Polar Traffic

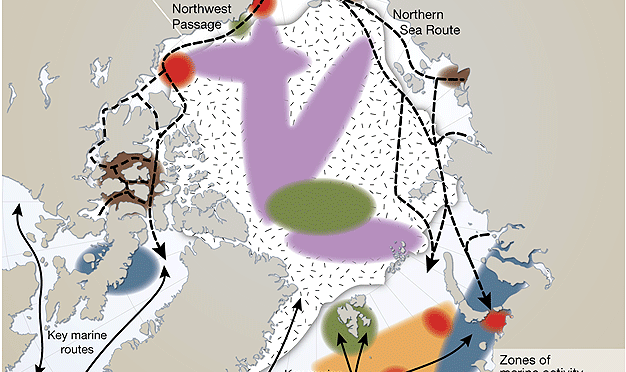

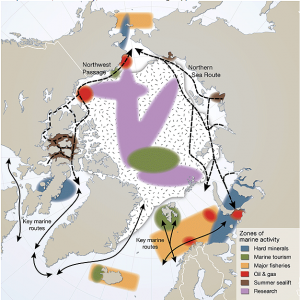

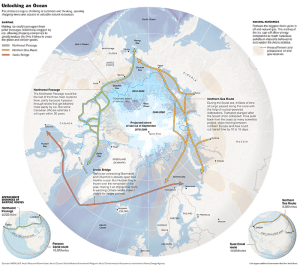

Traffic in the Polar Regions still has not met the expectations of some over-optimistic forecasts. The Northern Sea Route (NSR) experienced a dramatic reduction in traffic this year. Less than two dozen full transits were reported and initial figure indicate only 274,000 tons of cargo moved compared to 2013’s 1,356,000 tons. Though ice conditions in the NSR were somewhat more difficult in 2014, conditions were heavier in the Canadian Arctic.

Notably absent this year was an expected repeat Northwest Passage transit by Nordic Bulk after their landmark Nordic Orion voyage in 2013. Fednav’s latest arrival, MV Nunavik, did however make a westbound transit late in the season.

Routine destination traffic, which includes the resupply of Arctic communities and export of resources, continues to show incremental increases in both the NSR and Northwest Passage (NWP). However there has been some cooling of interest in hydrocarbon exploration over the past year, whether it is as a result of sanctions against Russia for their activities related to Ukraine, or uncertainty of regulatory environment in American waters.

In the Antarctic region, traffic statistics remain static, driven mainly by research, resupply of research stations and the occasional adventure cruise vessel.

Ice Ship Orders and Construction

The growing interest in polar ice shipping is being felt in ship orders and construction. Numerous ice class ships are on the order books, and some notable orders and deliveries are those of Nordic Bulk with their Baltic ice class new builds and Canada’s Fednav with delivery of their newest icebreaker cargo ship Nunavik. The latter made news with the first unescorted commercial cargo vessel transit of the Northwest Passage this summer.

Russia has announced and commenced the construction of their new design conventionally powered icebreakers as well as three LK60 nuclear powered icebreakers. Russia is also building a number of icebreaking search and rescue vessels to meet their commitment to increase SAR capability after wholeheartedly embracing the Arctic Council’s 2010 Arctic SAR agreement.

At the beginning of the year, Russia took possession of the novel oblique icebreaker, Baltica. Shortly after delivering the Baltica, Finland’s Arctech Helsinki Shipyard announced a contract to build three icebreakers for the Northeast Sakhalin oil and gas field. Perhaps the largest Russian driven high ice class construction is the DSME designed 170,000m3 icebreaking LNGCs to be built for LNG export from the new Yamal field. These ships will be operated by a number of companies including SOVCOMFLOT, MOL and Teekay over the life of the Yamal project. A fleet of six support icebreakers for port and channel clearing, as well as line support in heavier coastal ice will also be built. Three more ice class shuttle tankers were ordered from Samsung Heavy Industries by SOVCOMFLOT for delivery by April 2017.

China is building a new icebreaker to complement their secondhand Xue Long, delivery in 2016; Britain has begun the work to acquire a new 130m icebreaker for delivery in 2019; Australia intends to replace the Aurora Australis hoped for by 2018 with the bidding narrowed to three contenders in the fall; Germany is not far behind in plans to replace the venerable Polar Stern; and, Finland has a new Baltic LNG fuelled Icebreaker under construction and has announced a billion Euro plan to replace their current fleet of icebreakers in coming years.

India has also announced plans to build a polar research icebreaker to be operational before the end of the decade. Columbia has announced plans to build and send an ice-capable research ship to Antarctica while Chile’s president announced in December plans to build an ice-capable research ship for Antarctic service as soon as practicable.

Though the American built light icebreaker research vessel Sikiluaq entered service this past year, the United States and Canada continue to be mired in indecision or delays with respect to ice-capable ship construction. There are no clear plans to consider replacing the ageing United States Coast Guard’s polar class ships, and Canada’s much vaunted announcement of the acquisition of the new generation polar icebreaker, which was named by the government as the John G. Diefenbaker, has seen cost increases and delays in delivery. The original delivery of 2017, for the Diefenbaker has slid to the right, first to 2020 and now rumored to be 2022. Reports now indicate the original construction cost of $750m CDN has climbed to well over $1.2B CDN. Given the advancing age of Canada’s venerable icebreaking fleet, it is surprising that only one replacement has been approved.

The Royal Canadian Navy’s plans to build 6-8 ice-class Arctic Offshore Patrol vessels has experienced similar cost overruns and delays even before steel has been cut. News reports at the end of 2014 indicated the number of ships that could be obtained would likely be fewer than originally announced, and only three vessels could be built for the allocated budget.

Changes in Arctic Offshore

Russia’s almost frantic growth in Arctic exploration and exploitation over the past decade has taken a downturn in the past months. As a result of increasing sanctions put in place by European Union, the United States and other nations, and the rapidly dropping price of oil in the last weeks of 2014, Russia has either seen the gradual pulling away of western partners, or has terminated contracts themselves (such as the recent termination of contracts with Norwegian OSV operators), and reduced projections for hydrocarbon export. As a result, hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation activities in the Russian Arctic began to slow in the latter part of the year.

In the midst of pullbacks from exploration, Russia has continued to bolster their Arctic presence, opening the first three of ten Arctic search and rescue centers in 2014, taking delivery of the first of six icebreaking search and rescue ships and increasing naval presence capability.

Risks Remain Evident

Just as the situation with the Akademik Shokalskiy indicated in the Antarctic in the beginning of the year (in the latter part of the Antarctic shipping season), an incident with a Northern Transportation Company Limited barge adrift in the Beaufort Sea at the end of the Arctic shipping season highlighted the remote nature of polar shipping operations. In each case, the situations were exacerbated by the lack of nearby rescue resources. While the Akademik Shokalskiy eventually broke free on her own, the NTCL barge was left to freeze into the ice over the winter as the tug initially towing was unable to reconnect and no other resources were close enough to recover the nearly empty fuel barge.

Discovery of the Wreck of HMS Erebus

One long standing search and recovery mission did result in a very successful search this year as the Canadian Coast Guard ship Sir Wilfrid Laurier and onboard researchers from Canadian Hydrographic Services and Parks Canada discovered the well preserved remains of Sir John Franklin’s flag ship HMS Erebus in the waters near to King William Island in the Canadian central Arctic.

Under command of Sir John Franklin, HMS Erebus and Terror set out from England in the mid 1800’s in what was thought to be the most technologically advanced and therefore “bound to be successful” effort to discover and sail the Northwest Passage. Tragically, both of Franklin’s ships became hopelessly trapped in the ice, the crews eventually abandoned both vessels and were never seen alive again. Most of the Canadian Arctic was charted in the many searches at sea and from ashore in search of survivors, many relics were discovered including a note that described the abandonment, but the vessels themselves remained lost until this summer when HMS Erebus was discovered.

This post originally appeared in The Maritime Executive.

The Arctic region is estimated to have over $1 trillion worth of precious minerals and the equivalent to

The Arctic region is estimated to have over $1 trillion worth of precious minerals and the equivalent to  Most

Most