By Ching Chang

The South China Sea has turned into a hotspot for potential regional conflicts in recent years. Nonetheless, parties concerned have already tried their best efforts to establish certain mechanisms to prevent crisis and reduce tension together. The first significant initiative was the “Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea”, known as the DOC, signed by all the members of the ASEAN and the People’s Republic of China on November 4, 2002.

Although the Article Ten of the DOC explicitly noted with “The Parties concerned reaffirm that the adoption of a code of conduct in the South China Sea would further promote peace and stability in the region and agree to work, on the basis of consensus, towards the eventual attainment of this objective.”, yet no substantial progress has been achieved since then. On July 20, 2011, another joint statement signed by the ASEAN members states and the PRC known as the “Guidelines for the Implementation of the DOC” was noted as another milestone for “embodying their collective commitment to promoting peace, stability and mutual trust and to ensuring the peaceful resolution of disputes in the South China Sea.” Nonetheless, the Code of Conduct was never mentioned by the later established guidelines. It may also imply the actual pessimistic situation for formulating the South China Sea Code of Conduct.

According to the present structure for negotiating the South China Sea Code of Conduct, there are several arrangements that can be challenged since they may eventually undermine the legitimacy of the COC as an effective mechanism to affect behaviors of every party involved in theSouth China Sea.

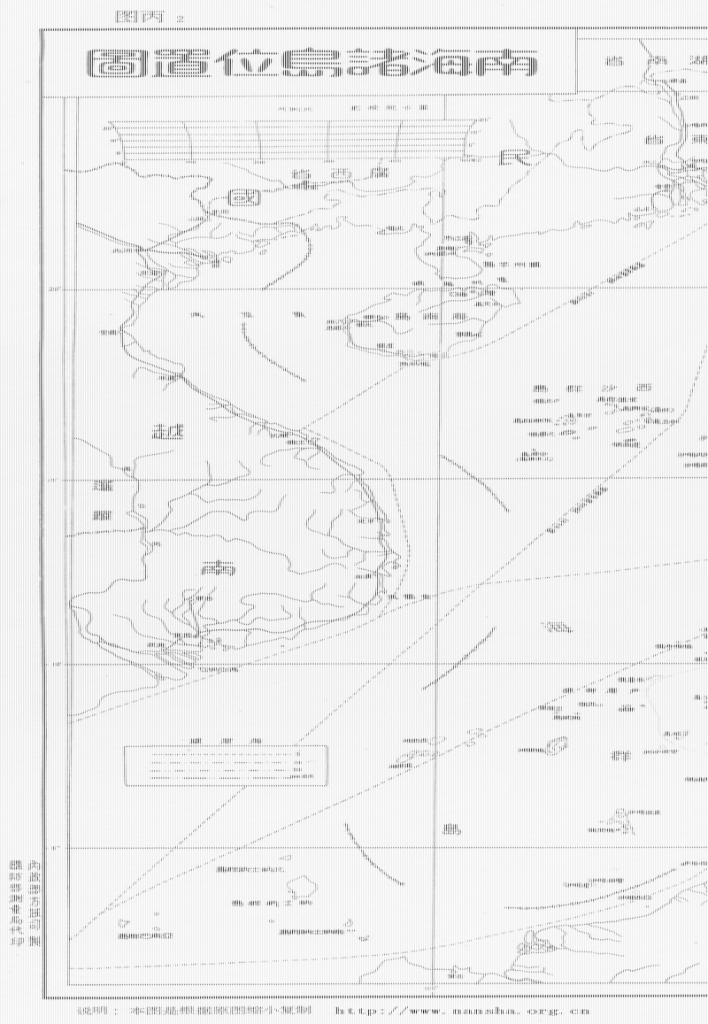

First, the Republic of China now in Taiwan was never invited to join the COC negotiation process. It is obviously opposed by Beijing for negating the ROC presence in the international community. And all ASEAN members follow the “one China” policy as the prior condition when they established the diplomatic relationship with the PRC. It is not surprised to see that the ROC is excluded from the collective effort so far. Nonetheless, the ROC is not only a claimant of the territories and waters of the South China Se,. Taipei is a substantial occupant of a major island, Tai-Ping Island, in the South China Sea. Further, Taiwan also actively conducts various maritime activities in the South China Sea. Without Taipei’s involvement and consent, how can the South China Sea Code of Conduct be a meaningful mechanism to assure the stability and peace in the South China Sea?

Compared to Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Singapore and Laos, the Republic of China should have more reasons to be involved in the negotiation process since all these ASEAN states noted above are not adjacent to the South China Sea at all. Taipei should also have the better reason than Jakarta to sit together with other claimants of the territories in the South China Sea since Indonesia is not even a claimant but only concerned of its Economic Exclusive Zone. Although Beijing frequently implies that all Taipei’s privileges and interests in the South China Sea will be guaranteed by the People’s Republic of China, the proposal has never been accepted by Taipei. Any assurance like this will not be recognized by ASEAN member states.

Second, nations’ individual interests in the South China Sea have not been totally covered by the negotiation process. As addressed by the Article Nine of the DOC, “The Parties encourage other countries to respect the principles contained in this Declaration;” how can we expect that states never involved in the negotiation process of the future South China Sea COC can be constrained by a mechanism that they never explicitly accept. Many states use the South China Sea as major sea lanes of communication to serve their maritime interests and supporting their national economic welfare. If we expect the South China Sea COC to be a meaningful document to assure the peace and stability in the South China Sea, it should allow more states to be involved in the codification process and even subsequently signing and ratifying the international decree.

Based on the flaws already mentioned, the author would like to propose a “Multi-chaptered South China Sea Code of Conduct” in order to make this document can be more sensible and functional also. The South China Sea Code of Conduct should be categorized into several chapters according to participants’ conditions. In another word, it should be modularized by function and status accordingly.

Those who are concerned with the situations in the South China Sea are encouraged to read the contents of the “Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea” and the “Guidelines for the Implementation of the DOC.” It is obvious that many terms are totally irrelevant to some ASEAN member states since they have no position to engage with those activities. To some extent, these ASEAN member states are so innocent to be kidnapped into a process that may not serve their true interests simply because of the plot to use ASEAN to balance the PRC in the South China Sea. On the other hand, for many states actually involved into activities in the South China Sea, the negotiation process does not consider preparing a document for them to participate so that establishing constraints on their behaviors or activities in the South China Sea is unlikely.

A multi-chaptered South China Sea Code of Conduct may allow states using the South China Sea for whatever reason to choose those chapters they would like to sign and promise to follow the code accordingly. Several chapters like environmental protection, fishery regulation, search and rescue, scientific research, climate report, oceanographic survey, anti-piracy and smuggling, nature preservation, sewage and waste process, navigation aid and regulation can be easily established with no controversy. For those codes that intentionally restrict behaviors enhancing future territory claim position, we should consider to replace the term of “claimants” into “occupants” so reducing the de jure proclamation by more objectively expressing the de facto statement.

This may be the only way to accommodate the Republic of China in Taipei and have it join this mechanism but not provoking Beijing. Beijing is very sensitive to anyone who violates the one China principle by accepting any term that may imply “Two Chinas” or “One China, One Taiwan.” Taipei has no intention to use the South China Sea Code of Conduct as a stage to irritate Beijing. Adopting the term of occupants to replace claimants may allow the specific chapter to be a description of realities in the South China Sea but not a statement of expressing political aspirations. The author would like to remind all the readers that without the Republic of China, the South China Sea Code of Conduct is only a self-deceived paper. Without all other states actually involved in the maritime activities in the South China Sea to promise following the terms noted in the chapters they choose to sign, the South China Sea Code of Conduct cannot be meaningful.

Chang Ching is a Research Fellow with the Society for Strategic Studies, Republic of China. The views expressed in this article are his own.