By LCDR Christopher Nelson, USN

Consim Press has published a fantastic solo player wargame in Silent Victory: U.S. Submarines in the Pacific, 1941-1945. With game design by Gregory M. Smith, Silent Victory offers a little bit of everything for someone looking for an immersive, historical naval wargame that is easy to play yet detailed enough to be fulfilling for an advanced gamer.

Consim Press has published a fantastic solo player wargame in Silent Victory: U.S. Submarines in the Pacific, 1941-1945. With game design by Gregory M. Smith, Silent Victory offers a little bit of everything for someone looking for an immersive, historical naval wargame that is easy to play yet detailed enough to be fulfilling for an advanced gamer.

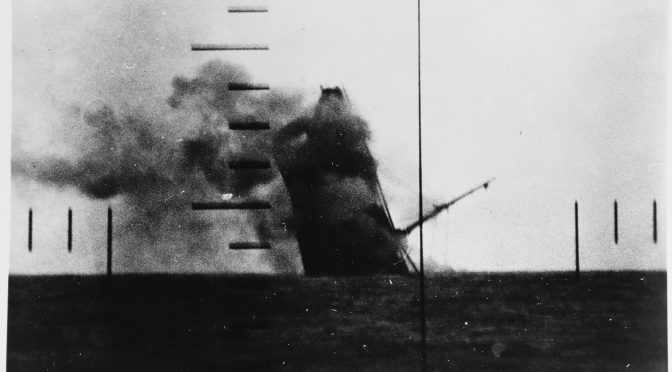

“EXECUTE AGAINST JAPAN UNRESTRICTED AIR AND SUBMARINE WARFARE.”

– Chief of Naval Operations

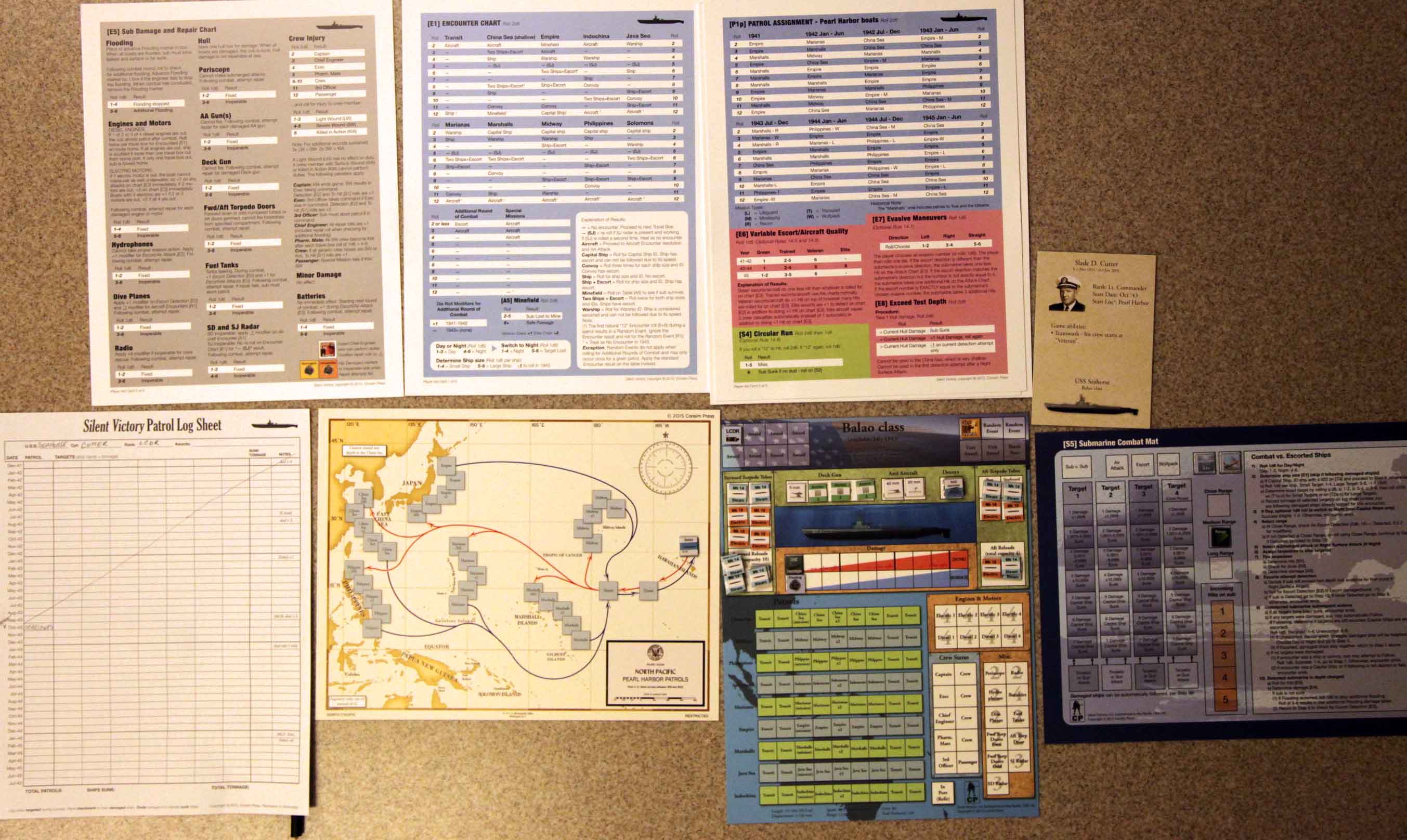

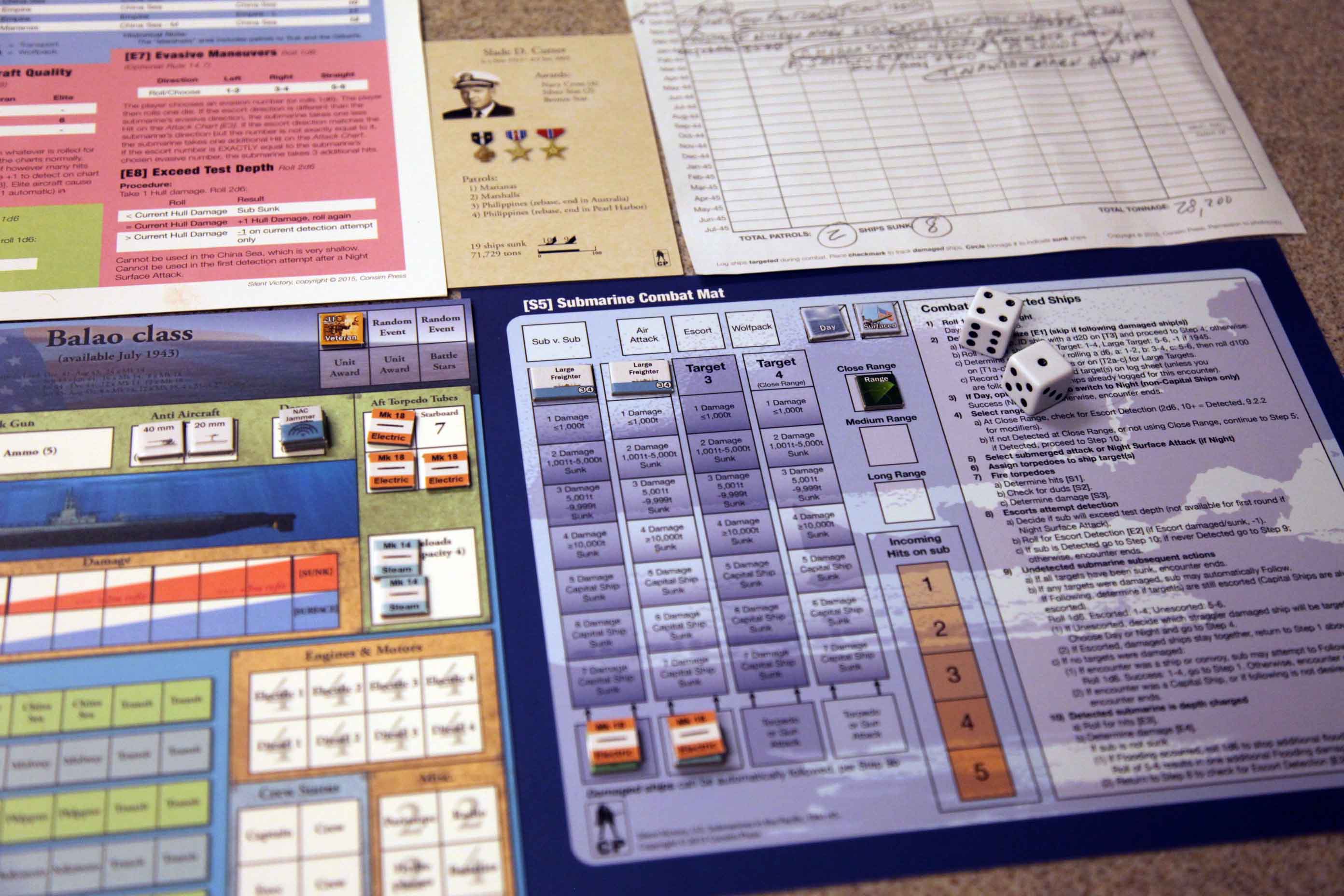

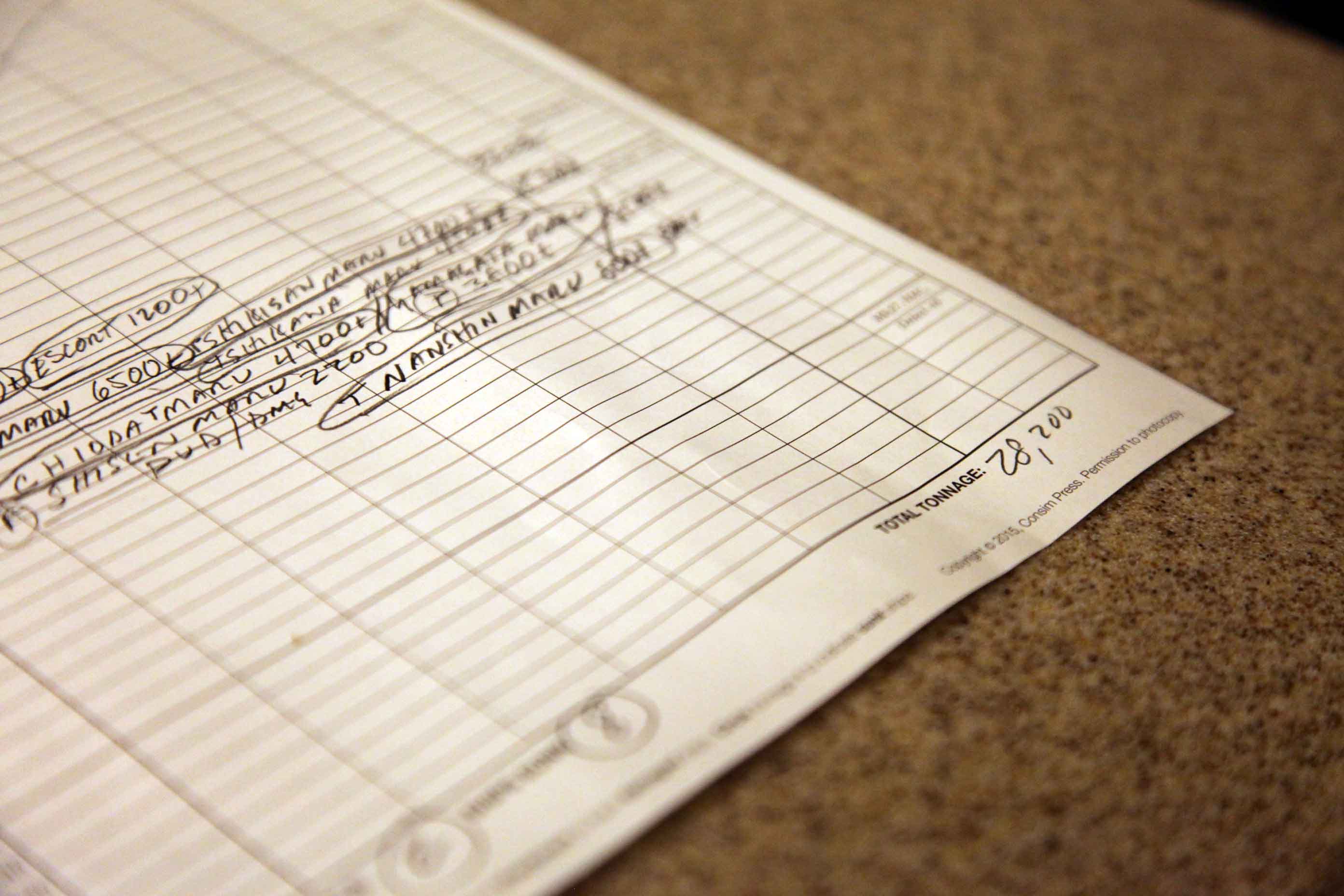

It’s 1941 and you are a U.S. sub skipper in WWII; tasked to sink Japanese ships — tankers, freighters, personnel carriers, escorts, and capital warships — wherever you find them in the Pacific. You can play as a historical WWII sub skipper or, rather, you can simply play as yourself and choose the class of submarine you’d like to command. You can even name the boat. When you crack open the box you’ll be impressed with how well Consim has done here. The patrol maps, captain cards, combat mats, and submarine display mats are all printed on a heavy card-stock and the print quality is excellent. Also included in the box are the required dice and plenty of copies of the Silent Victory patrol log sheet — important, as it is used to record the total number of tons you sink on your combat missions.

Game Setup

The game’s “footprint” is moderate — you’ll need a dinning room table or some floor space to lay out most of the game’s playing mats. However, if you are space constrained, you can simply stack some of the player mats on top of one another and then retrieve them when it is time to reference a mat during a roll. Below you’ll see my setup, and even though I had ample table space, I still stacked some of the mats (namely, the target mats which list all Japanese ships), until I needed them. This is what it looks like:

Game setup is tedious for folks playing the game for the first time. The only reason for this, really, is that you’ll have to punch out all of the game pieces that come with the game. These include everything from Japanese ships to markers that show awards and ranks. Future game setup is much easier if you take the time to organize the game pieces into plastic bags — grouping munitions in one, for example, and then Japanese ships in others, awards in one, torpedoes in another, and so on.

Now, before you start sinking Japanese ships, the basic setup goes like this:

1.) You decide if you want to play a historical skipper, which includes a specific submarine and starting period (you don’t have to start in 1941), to include patrols (e.g,. The Marianas, The Philippines, The Marshalls, and more). Many of these skippers already come with roll bonuses due to experience. The other option is you simply pick a submarine class and starting point (often dictated by when the submarine class enters service) and then roll dice for patrol areas, next;

2.) You’ll load out your submarine with the good stuff — torpedoes in forward and aft tubes, and ammo for the deck mounted guns on your specific submarine type. The game makers made this easy as each submarine combat mat states on the top of the mat exactly the type of torpedoes available for that submarine. For most, this was a mix of MK14 (steam) and MK18 (electric) torpedoes. Finally;

3.) Fill out your Silent Victory submarine log with the name of the sub, your captain’s name, your rank, and place your boat marker at your home port — now you’re ready to begin.

Gameplay

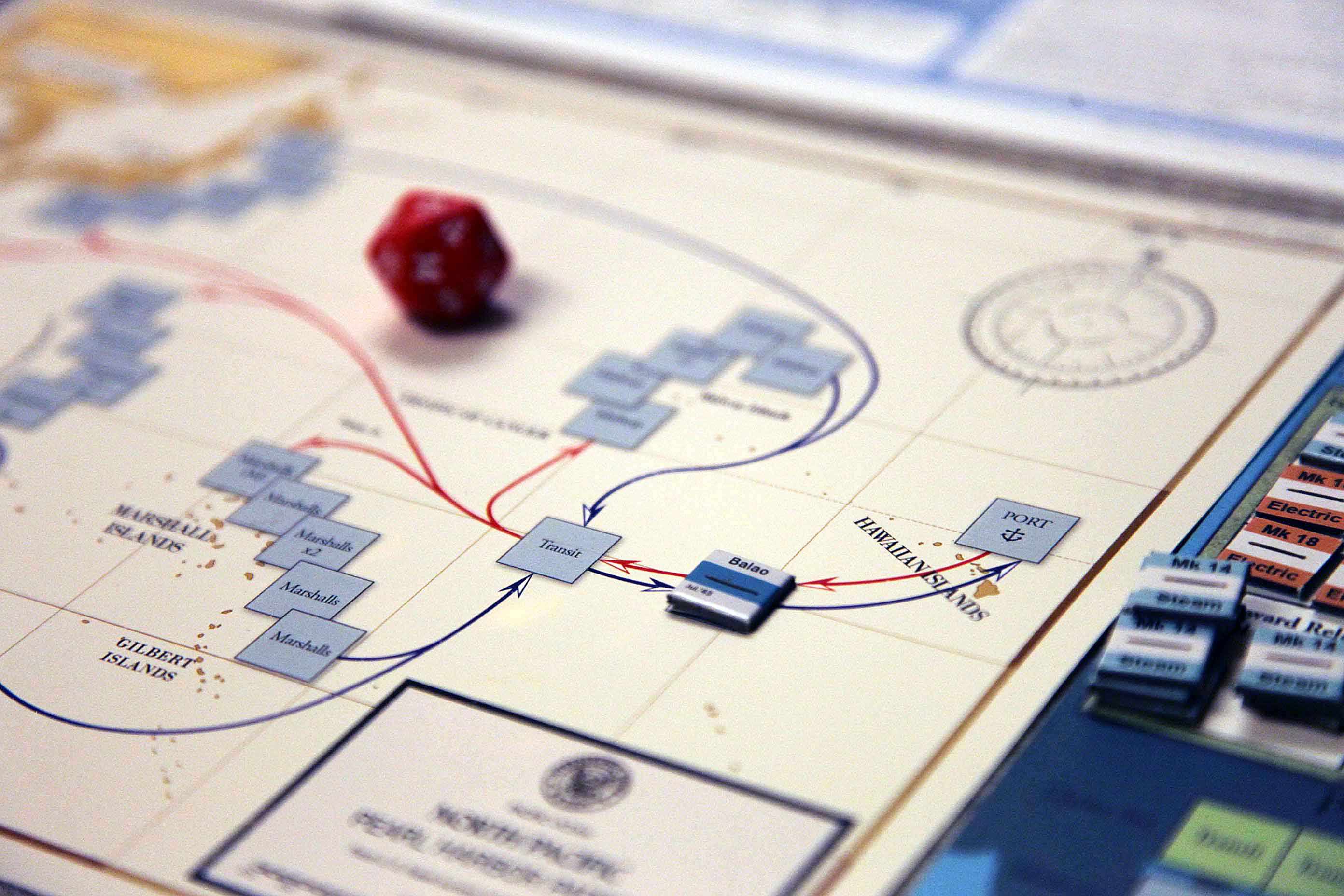

Once you’ve identified your patrol area, you move your submarine marker through the transit points and into the boxes located in your patrol areas. At each point, to include transit points, you’ll roll dice to see if you encounter enemy units.

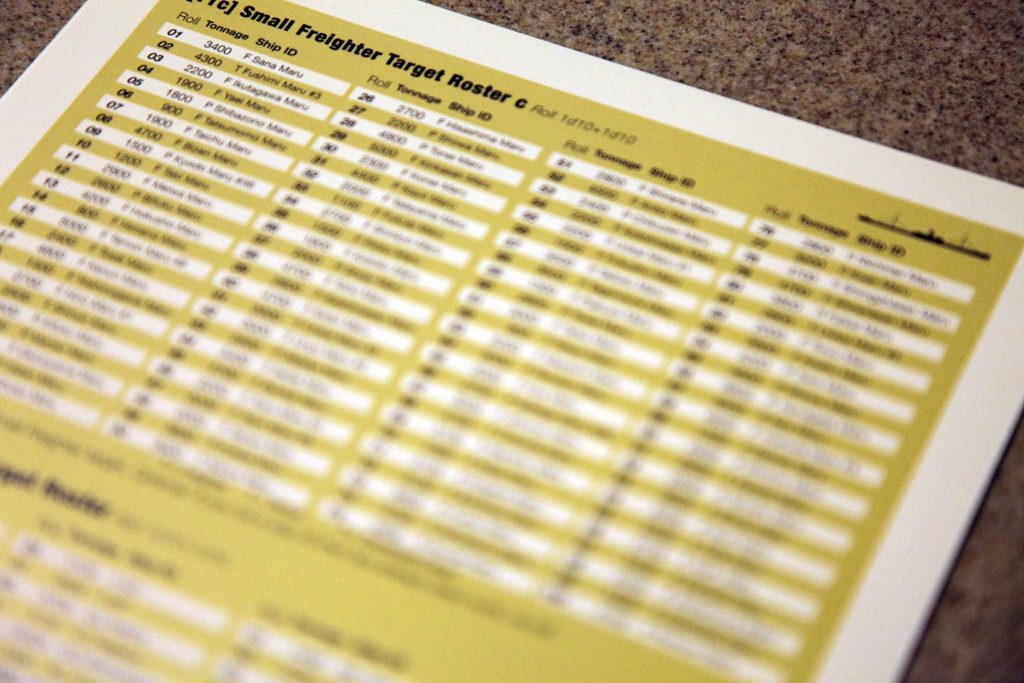

While transiting, you might come across an aircraft or maybe a lone ship, but this is rare as roll of the dice go. Once you enter your patrol areas, however, the possibilities of rolling an encounter increase. For encounters, you can run into warships, convoys with escorts, or unescorted ships.To the game designer’s credit, they’ve assigned different probabilities per year as to what ships a submarine skipper might encounter. For example, it was tough to find a large Japanese freighter or Japanese capital warship still afloat by 1945.

Next, when you encounter a Japanese merchant vessel or Japanese warship, you can attack it (you can also choose to not attack). You will roll for day or night. Are you surfaced or submerged? You then assign the type and number of torpedoes and/or deck gun shots against your target(s). Then you will roll to see how effective each shot is. If not already obvious, dice will determine a lot of what occurs in this game — damage to your ship, damage to Japanese ships, being detected, dud torpedoes, and more. Oh, did I say “dud torpedoes?” Yes. This was a problem in WWII. It is also one of the things that make this a challenging game.

For every torpedo you fire, you’ll roll a 1d6 dice for a dud. Roll a 1 or 2, well, you are out of luck. It might have hit, but it didn’t explode. Dud. This happened to me at least three times in two patrols. It was a fact — the U.S. Navy had a torpedo problem. Clay Blair Jr.’s magisterial book Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War against Japan made this clear:

“…[T}he submarine force was hobbled by defective torpedoes. Developed in peacetime but never realistically tested against targets, the U.S. submarine torpedo was believed to be one of the most lethal weapons in the history of naval warfare. It had two exploders, a regular one that detonated it on contact with the side of an enemy ship and a very secret “magnetic exploder” that would detonate it beneath the keel of a ship without contact. After the war began, submariners discovered the hard way that the torpedo did not run steadily at the depth set into its controls and often went much deeper than designed, too deep for the magnetic exploder to work.”

Blair notes that not until late 1943 would the U.S. Navy fix the numerous torpedo problems.

For my recent game play, I decided to play as Lieutenant Commander Slade Cutter, USN. Cutter, who originally intended to be a professional flutist, ended the war with four Navy Crosses, two Silver Stars, a Bronze Star with combat “V,” and a Presidential Unit Citation. He sank over 140,000 tons of Japanese shipping. In two hours of gameplay I couldn’t come close to that number. But we had a good run. I played the first two patrol areas listed on Cutter’s captain card: The Marianas and The Marshall Islands.

To summarize two patrols and two hours of play, these were the highlights:

- I encountered an escorted ship in The Marianas. I rolled a dud for one MK 18 but assigned enough torpedoes to sink the freighter and its escort on subsequent rolls.

- I encountered an aircraft. I rolled a successful crash dive and staved off any damage.

- I was rebased to Australia following a “random event” roll. (These may occur once in a patrol.)

- I refit my submarine when I rebased in Australia.

- On my Marshall Islands patrol I encountered a three ship convoy with an escort. I sunk all three merchant vessels, but had to finish the last merchant vessel off with the deck gun (5”) — which I assigned at the last moment.

- I encountered a warship which I decided not to engage.

- And I returned to base after two successful patrols and earned two battle stars, a navy cross, and rolled for promotion to Commander — which was successful.

I was fortunate. During my two patrols, when I encountered escorts and rolled for detection, I always rolled “no detection.” If I had been detected, I would have had to roll for depth charge destruction. This includes flooding, damage to systems, hull damage, and sailors injured or killed. Not good. But I managed to get everyone back home after two patrols with all fingers and toes. Still, the risk was there every time I decided to engage a convoy with escorts. So, why is this game so much fun?

Conclusion

There are three reasons why this game succeeds.

First, historical accuracy. From the problems with torpedoes, to the detailed lists of Japanese merchant and capital ships, or to the specific weapons load out of each U.S. submarine in WWII, it is all there. The makers of this game did not cut any corners. They did their homework and tried, I think successfully, to incorporate significant historical facts into the gameplay.

Second, a risk/reward based gameplay experience. Every decision you make — from the torpedoes you use to deciding if you want to attack submerged and at close or long distance — incurs risk. There are numerous tradeoffs. For instance, you can attack from long distance submerged, but you suffer a roll modifier and risk not hitting your target. Or, you can be aggressive, and attack at close range, surfaced at night, which may increase your chance of hit but also increase your chance of detection. It just depends.

Finally, simple game rules. Complicated games are no fun to play. As a player, I don’t want to spend 10 minutes looking up rule after rule in a rulebook the size of a encyclopedia. In Silent Victory, the designers have done us a favor. The rules are clearly written and extensive, and after a single read through I referred to them occasionally. But more important, the combat mat has the dice roll encounter procedures printed on it, all within easy view. Also, the other mats all have reference numbers and clearly identify which dice should be rolled for what effects. It is all right there on the mats. This makes for a fun, smooth playing experience. And finally, if I were add another reason why this game is worth your money, it is the game’s replay value. You can conduct numerous patrols and no two patrols will ever be the same.

Silent Victory is a fun naval wargame that will appeal to the novice or expert gamer – and maybe you’ll learn something along the way.

Lieutenant Commander Christopher Nelson, USN, is a staff officer at the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The opinions here are his alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Navy or the Department of Defense.