By Joseph O’Connell

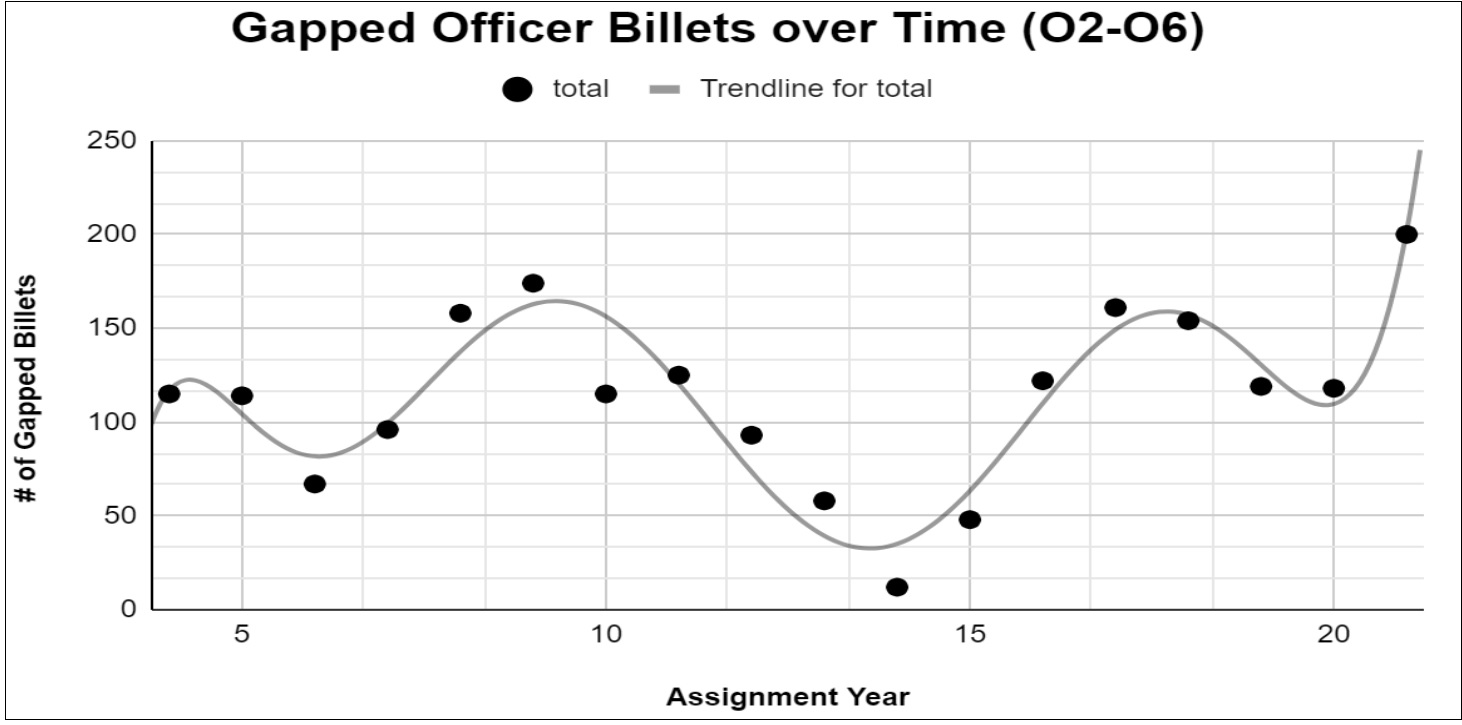

The Coast Guard is facing a looming afloat officer shortage with no good options on the table. With roughly 3.5%* of all CG officer billets currently gapped, and a particular shortfall impacting mid-grade (O3/O4) officers the Coast Guard needs to explore creative solutions to address the pending crisis. At the conclusion of assignment year 2021 (AY 21) the Coast Guard reported being 213 officers short, with a whopping 166 of those being O3 or O4’s, a growing shortfall of experience that cannot be easily resolved.1 While this might seem a rounding error to larger armed services, this represents a significant percentage of the Coast Guard officer corps. To put in context, if the U.S. Navy were facing a similar shortage, they would have gapped approximately 1,960 officer billets, a dearth that would undoubtedly impact operational readiness. This shortage grows more acute when considering the critical billets O3 and O4 officers fill aboard Coast Guard cutters: Operations Officers, Engineer Officers, Executive Officers, and Commanding Officers, depending on the cutter class.

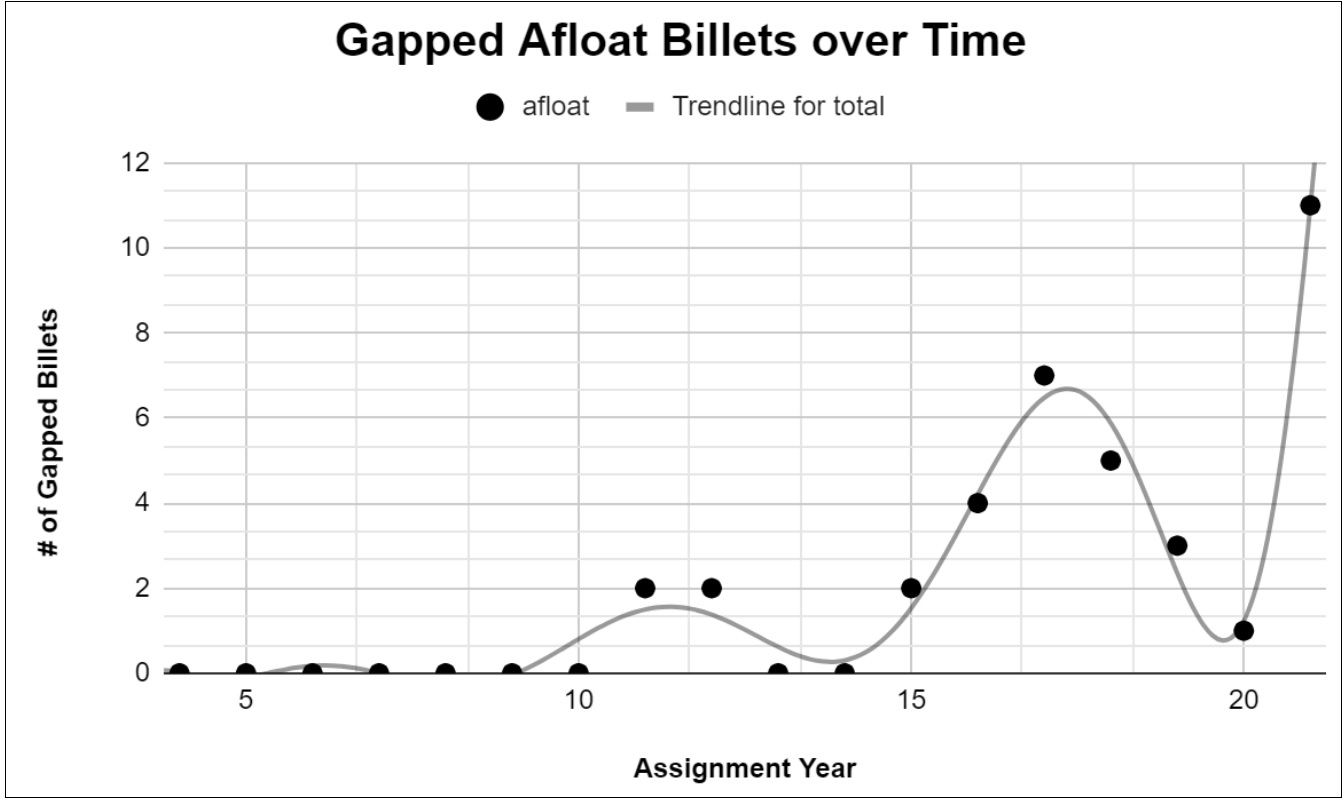

Utilizing the last 18 years of officer assignment data, a picture of a rapidly declining officers corps forms, with current trends indicating that implemented officer retention tools are failing1. Figure 1 shows the rapid increase in missing officers over time, highlighting the unique nature and acuteness of this particular crisis.1,2 As shown in Figure 2, the officer shortage is extremely concerning for the afloat community and was correctly predicted in 2015’s The Demise of the Cutterman2. Of note, AY21 was the highest number of afloat billets gapped, verifying the more pessimistic predictions made by CDR Smicklas. As the Coast Guard continues to bring new hulls online while operating legacy assets the demand for afloat officers will far outstrip the limited and dwindling supply, with projections anticipating a 25% increase in cutter billets from current levels.3

Armed with this knowledge, there are several options left to decision-makers. The readily apparent options, from least to most intrusive are: letting the crisis play out, ameliorating critical shipboard habitability shortfalls, prioritizing afloat officers, and major force restructuring.

Wait and See

The least intrusive option the Coast Guard could pursue is a “wait and see” strategy, wherein program managers would assess the impacts of current retention policies impacts on officer retention and the afloat billet gap. In its current form, this exclusively entails the recent afloat bonus program.5 It is possible that the afloat billet gap will shrink as more officers elect to return afloat in pursuit of bonus money or career path incentives (arguably not the right reasons to go afloat).

There is a historical argument in favor of waiting as well, traditionally during economic boom cycles the service has difficulty retaining officers, while during economic downturns the officer corps is closer to full strength, this can be seen in the years following the great financial crisis when the officer billet gap was greatly reduced, only to steadily rise as the economy rebounded in the mid-2010s.9 Just as a prudent mariner would not hazard their vessel based on scanty radar information, Coast Guard programmers and planners cannot place bets on the future of the service based on unknowable economic outlooks. This strategy runs the risk of inaction and a deepening crisis while maintaining current priorities in hopes that new assets will alleviate habitability issues and that afloat bonuses will deepen the afloat talent pool. 8 If an economic crisis fails to materialize, or the officer corps reacts differently than during a financial crisis there is a chance that this strategy fails catastrophically and the afloat gap grows, adversely impacting operations.

Prioritize “Sea Service Attractiveness”

Habitability

The next actionable item the Coast Guard can pursue to mitigate the exodus of afloat officers is prioritizing sea service attractiveness. By and large, this falls into two buckets: 1) addressing egregious shipboard habitability issues and 2) “nice to have” incentives such as Wi-Fi, preserving port calls, and reduced work days. On the latter measure, the Coast Guard has made significant investments in UW connectivity and bandwidth.

These creature comforts do not, unfortunately, extend to legacy Coast Guard assets, namely the Famous and Reliance class, medium endurance cutters, which suffer from debilitating habitability issues. These issues range from the whimsical– water intrusion flooding staterooms every time it rains to such an extent that it was re-christened “the waterfall suite,”—to the downright dangerous 2 ft. diameter holes hidden by appliances such as laundry machines or controllable pitch propeller systems that rely on emergency relief valves to regulate system pressures. Furthermore, it is not uncommon in the medium endurance cutter fleet to hear sea stories of tools falling into the bilge and puncturing the hull.

Compounded, these unappetizing work environments significantly diminish the already austere nature of serving aboard ship. These unfortunate conditions are the result of years of policy decisions de-emphasizing legacy asset sustainment in favor of other priorities, with newer hulls promising to resolve habitability issues once online. Building new cutters has taken longer than anticipated and legacy medium endurance cutters, the bulk of the Coast Guard Atlantic Area’s forward operating assets, are now expected to operate for another 5-15 years4. Given this timeline, one “down payment” the Coast Guard can make for the health of its future afloat officer corps, is addressing the dire habitability issues aboard its medium endurance cutters. Paired with the “nice to have” initiatives, such as shipboard Wi-Fi, money spent on increasing the attractiveness of sea duty could pay significant dividends in the years to come.

The Coast Guard should increase habitability and work-life balance, through major investments throughout the fleet, particularly in the Medium Endurance Cutter (MEC) fleet. Some easy actions to take would be increasing cutter maintenance budgets to repair long overdue crew comfort issues, earmarking funds to upgrade or install rec/morale equipment that can be used underway, increasing maintenance periods to promote work-life balance, and decreasing the amount of homeport maintenance work completed by the crew. While none of these are ‘free’ and come with associated costs (funds being taken from other priorities, reduced operational time, more workload for shoreside maintenance units, etc.), they are worthwhile to explore in order to avert a major afloat staffing issue.

Incentives

If sea duty attractiveness is increased, then an organic shift in officer billet preferences may occur and naturally fill the afloat gap. Increasing sea duty attractiveness is complex and difficult, and a myriad of solutions are currently being explored by the Coast Guard, namely afloat department head and XO bonuses5. Given that these bonuses may not prove to be effective the Coast Guard should be investigating additional incentives, starting with the least desirable afloat units. While monetary incentives through bonuses are very cogent, additional incentives could also be explored, such as offering geographically stable follow-on tours, weighing sea time when considering candidates for post-graduate studies, or more drastically increasing promotability for afloat officers. While none of these is a panacea for increasing sea duty desirability, these among other proposals should be explored.

Select and Direct

The proverbial easy button is to simply fill all afloat billets at the expense of the other communities, forcing sector officers, aviators, and support officers to be chronically understaffed while mandating that all afloat billets be filled. While this solution is theoretically easy to implement from a policy perspective, it may backfire as other operational and support communities suffer more acutely under staffing shortages, degrading joint mission capabilities and depleting the CG ‘brand’. More concerning is forcing officers into billets they have no interest (or expertise) in, leading to dissatisfaction at work, poor performance, and incompetence, all of which can congeal into toxic workplace environments aboard cutters, exacerbating the cutterman shortage through a vicious cycle. However, if afloat billets are prioritized while taking concrete steps to promote afloat habitability and work-life balance, there could be a natural shift in billet preference among the officer corps.

Prioritizing afloat billets at the expense of other communities puts ‘butts in seats’, averting the critical crisis of a rapidly dwindling afloat officer corps, but is not a sustainable long-term solution. It is worth noting, a solution that quickly closes the afloat officer gap while incentivizing officers to return afloat still proves elusive, as the Coast Guard started utilizing monetary incentives over the past 2 assignment years without tangibly reducing either the pending staffing shortage or reducing the number of ‘afloat’ billets gapped.1

Major Overhaul

Finally, if the Coast Guard is unable or unwilling to fill billets and can still meet its statutory mission objectives, it could pursue more extreme options involving a major force restructure of officer billets. This restructuring could take multiple forms, including heavier reliance upon automation technology, reducing afloat officer billets, replacing officers with senior enlisted, reducing shoreside support billets, and mandating additional rotations into the cutter fleet. Each of these solutions harbors unique pitfalls.

A forward-looking solution is to reduce officer manning on future platforms such as the OPC, while simultaneously reducing officer billets on existing high-technology platforms, such as the WMSLs and HEALY. Given that industry vessels operate with manning in the teens for similarly sized vessels, it is entirely feasible to sail Coast Guard cutters with a fraction of the existing billet structure. These vessels rely heavily upon automation technology such as machinery control software (MCS) and utilize a different maintenance philosophy that emphasizes heavy depot periods and limited organization (crew) level maintenance6. However, by doing this the Coast Guard would accept significantly increased operating risks (by reducing organic crew casualty response capabilities), reduced operational effectiveness (fewer personnel to staff operational missions, such as law enforcement teams, migrant watchstanders, or defense missions) a reduced talent pool, among other serious consequences. Over-reliance on technology to reduce manning has proven troublesome in the recent past (see LCS and original WMSL manning concepts), and current automatic control systems do not replace a trained technician. 7

Another major restructuring action would be to fill O3 and O4 billets with more junior (to the billet) officers or senior enlisted personnel. While pursuing either action would serve as a temporary salve, both options harbor risk, officers junior to the traditional grade may lack the appropriate experience to serve as an Operations Officer or Executive Officer for example. Meanwhile, filling junior officer billets with qualified warrant officers or senior enlisted personnel stymies the training pipeline for future commanding officers.

A final drastic option would be to reduce current staff, support, and other non-afloat billets for critical pay grades and enforce an afloat tour requirement at those grades. While a guaranteed way to fill vital afloat jobs, this could have cascading effects on the afloat community, and the officer corps writ large. Reducing the number of support billets could degrade the quality of cutter support and sea duty attractiveness may suffer. This move could lead to an exodus of officers who joined the Coast Guard for different reasons than pursuing a career afloat.

Similar to ‘prioritizing the cutterman’, this would reduce the afloat officer gap, but may end up damaging the officer corps more than it helps. On the surface, alternative solutions are capable of solving the afloat officer gap, but a quick analysis reveals that they would have significant costs that may outweigh their benefits.

Shoal Water on Port and Starboard

On paper there are a variety of straightforward solutions to reduce the U.S. Coast Guard’s afloat and overall officer shortage, including leaning into automation/optimization technology, replacing current afloat officer billets with senior enlisted or more junior officers, restructuring the support officer billets and forcing pay grades to go afloat. Unfortunately, all of these solutions have deleterious consequences that increase the risks of operational units, (while decreasing effectiveness), and potentially damage the long-term health of the Coast Guard officer corps.

To avoid the worst of these consequences, the “least bad” option for the Coast Guard is to prioritize cuttermen and fill afloat billets at the expense of other officer specialties, while simultaneously increasing sea duty attractiveness to mitigate the consequences of selecting and directing. These measures are contingent upon increasing cutter habitability and sea duty attractiveness. Here, the Coast Guard must look to the least habitable cutters —the medium endurance cutter fleet— and work to make these units more desirable by increasing crew comfort underway and maximizing homeport downtime.

Lieutenant Joseph O’Connell is a port engineer for the medium-endurance cutter product line, tasked with planning and managing depot maintenance on five Famous-class cutters. He previously served in USCGC Healy (WAGB-20) as a student engineer and USCGC Kimball (WSML-756) as the assistant engineer officer. He graduated from the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in 2015 with a degree in mechanical engineering and from MIT in 2021 with a double master’s of science in naval architecture and mechanical engineering.

These views are presented in a personal capacity and do not necessarily represent the official views of any U.S. government department or agency.

Note: due to the opaque nature of available billet vacancies, vacant afloat billets may not be true shipboard assignments, afloat training organization (ATO), select CG-7 jobs and others may be coded as “afloat,” obfuscating the true shortage.

*3.5% was calculated in the following manner: (Total # of officers-total gapped billets)/(total # of officers). This formula assumes there are no over-billeted positions, which is not entirely accurate, but serves as a decent proxy.

References

1. Assignment Year Data from Coast Guard Messages: ALCGOFF 142/04, 062/05, 048/06, 048/07, 082/08, 072/09, 064/10, 038/11, 030/12, 029/13, 025/14, 025/15, 043/16, 057/17, 032/18, 061/19, 068/20, 048/21, 023/22

2. Demise of the Cutterman, CDR Smicklas, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2015/august/demise-cutterman

3. State of the CG 2021, https://www.mycg.uscg.mil/News/Article/2533882/sotcg-get-all-the-details-on-the-commandants-announcements/

4. Report to Congress on CG Procurement, April 2022, https://news.usni.org/2022/04/05/report-to-congress-on-coast-guard-cutter-procurement-15

5. All Coast Notice: 105/20 Officer Afloat Intervention

6. CFR 46 Part 15: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2017-title46-vol1/xml/CFR-2017-title46-vol1-part15.xml

7. Unplanned costs of unmanned fleet, Jonathan Panter, Jonathan Falcone, https://warontherocks.com/2021/12/the-unplanned-costs-of-an-unmanned-fleet/

8. Federal Reserve, Financial and Macroeconomic Indicators of Recession Risk, June 2022;

10. https://www.npr.org/2011/07/29/138594702/a-weak-economy-is-good-for-military-recruiting

Featured Image: A member of Maritime Security Response Team West watches as a Sector San Diego MH-60 Jayhawk helicopter approaches the flight deck of the Coast Guard Cutter Waesche (WMSL 751) cutter off the coast of San Diego, March 29, 2023. (U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Taylor Bacon)