Earlier this year, United States Naval Academy Museum hosted a debate on the future of aircraft carriers (with parallel debate on twitter under #carrierdebate). It is a timely debate as the utility of aircraft carriers is under review in the face of the proliferation of Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2AD) systems. Critics argue that current aircraft carriers are too vulnerable in highly contested environments and too crucial to lose. Indeed, ever more precise, maneuverable, and swift anti-ship missiles (ASM) and silent submarines make certain types of environments overly prohibitive for aircraft carriers. However, this is not an entirely new situation. In fact, sending aircraft carriers close to coastlines and into the littorals has always been dangerous and against their designed purpose.

Ever since the commissioning of the ex-Varyag into the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) as the Liaoning (CV-16), speculations have taken place as to its tactical, operational, and strategic implications. With Taiwan classified as one of China’s “core interests”, and due to the protection (however ambiguous) offered by the US under the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979, Taiwan remains a prime hotspots with the potential to escalate into an all-out great power war. Thus, various analysts have engaged in discussions on the Liaoning’s role in a potential crisis over Taiwan. However, in doing so, it is better not to fall for the allure of focusing on the hardware capability over doctrine, tactics and the nature of the specific theater.

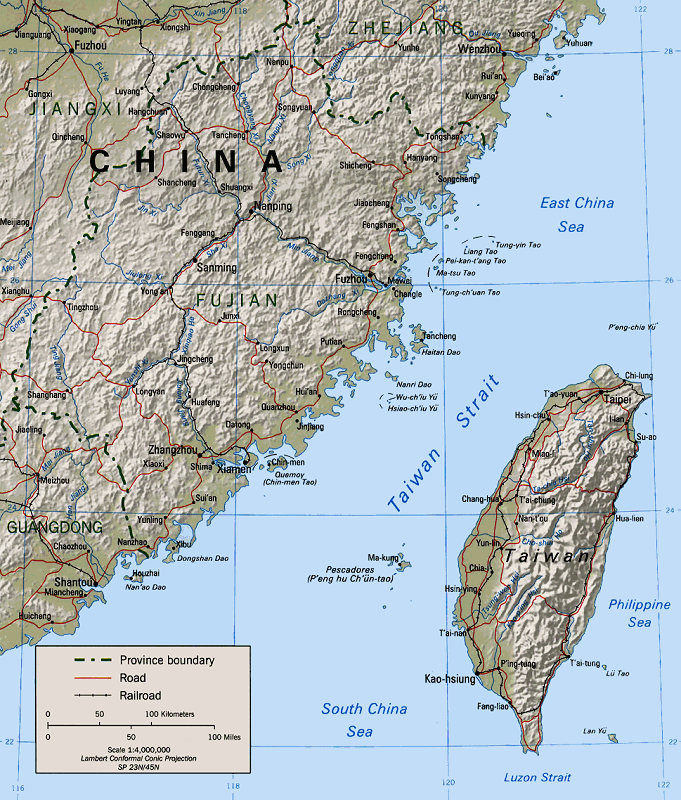

An examination of tactical and operational situations encountered by Carrier Strike Groups (CSG) through the Taiwan Strait reveals that adding a hypothetical Chinese carrier group’s presence does not augment existing the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN)’s strategy. Instead PLAN doctrine relies on assets in the form of saturation missile attacks, submarines, fast missile boats and other Chinese A2AD elements. It is worth mentioning that these capabilities were already present in the the Taiwan Strait during the 1995-96 missile crisis. Being close to an enemy’s land-based assets poses a severe risk to the CSG’s survivability. Its combat effectiveness, is significantly diminished in the narrow waters of Taiwan Strait during high intensity combat conditions. In essence, the PLAN already had sufficient capabilities in place in 1996 such that sending a CSG into the Taiwan Strait would be a suicidal endeavor. The situation has only become more challenging for the US Navy in recent years not because the PLAN has acquired an aircraft carrier of its own, but rather due to the fact that China has greatly enhanced and modernized its existing A2AD capabilities.

The common reference to the 1996 deployment of aircraft carriers during the Taiwan Strait Missile Crisis as an indication of what could happen should the situation between China and Taiwan escalate into a shooting war suggests that there are two common misconceptions about the 1995-96 crisis. In late December’s piece for The Diplomat, Vasilis Trigkas presented interesting argument on the presence of aircraft carriers in the Taiwan Strait. In particular, he notes:

Memories from 1996 – when Chinese missile tests in the strait prompted U.S. President Bill Clinton to order two fully armed carrier battle groups to pass through the Taiwan Strait – have shaped the strategic operational codes of the Chinese military and the Central Politburo. While China might have had the military resources to sink U.S. naval forces in its close periphery (quantity has a quality of its own) the strategic escalation that an attack against a U.S. carrier would trigger led Beijing to de-escalate. Since the importance of Taiwan’s reunification with the mainland remains an indispensible argument in the PRC’s rhetoric on the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, China’s officials have long strategized about how to neutralize U.S. operational superiority in the event of a new strait crisis. The 2008 acquisition of an old Soviet aircraft carrier from Ukraine should be seen as an extension of this goal. This carrier is the missing piece in China’s strategic puzzle in its first island chain and adds new strategic variables to a Sino-U.S. clash over Taiwan.

First, contrary to popular belief, in March 1996 neither of the two deployed CSGs (Carrier Group Seven headed by CVN-68 Nimitz and Carrier Group Five centered around CV-62 Independence) entered Taiwan Strait (p. 110). Nimitz was deployed in the Philippine Sea ready to assist the Independence Battle Group deployed to the east of Taiwan. Indeed, earlier in December 1995 the Nimitz battle group did pass through the Taiwan Strait, but it was several months after Chinese first missile tests close to Taiwan in July 1995. Moreover, US officials back then believed that the passage went unnoticed by Beijing (p. 104).

Second, in 1995 and 1996, the issue at stake was Beijing displeasure with Taiwan’s effort to establish itself as a new democracy, demonstrated by then President Lee’s visit to Cornell University and the island’s first free presidential election in 1996. Beijing did not de-escalate because of the presence of the two CSGs but because it had made its point. However displeased the Chinese leadership was back then, no one has seriously contemplated further escalation. Moreover, China could very well have another motivation, testing the limits of US strategic ambiguity across the strait as they had tested the 1954 Taiwan-US defense alliance during the 1958 Taiwan Strait crisis. In that sense, deployment of two CSGs gave Beijing the indication that the US would indeed intervene should the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) decide to use deadly force against Taiwan.

Thus, the presence of the Nimitz and Independence CSGs in Taiwan’s proximity in 1996 should be understood as a symbolic gesture of the US commitment to the peaceful solution of cross-strait relations. It is doubtful that the acquisition of the Liaoning would deter Washington should it decide to demonstrate its resolve again. With the other assets that the PLA has been busy deploying in a meantime, now, that is all different story.

Trigkas argues that in 1996 the Chinese backed off because targeting US aircraft carriers would escalate the conflict out of proportion. Having an aircraft carrier and deploying it in advance of an intervening USN CSG would push the escalation ball to the US’ corner. Henceforth, it would be the US who would have to take the first shot because the Chinese CSG would block its way. Given that in 1996 the use of force was off the table and the crisis was all about making a political stance without intention to escalate, would a Chinese aircraft carrier prevent future US intervention by making itself too (politically) valuable to be attacked?

Not since World War II has the world seen any significant battle fought between rival carrier groups, and just as the carrier replaced the battleship through asymmetric means (the range of the onboard aircraft negated the firepower, speed and armor of a conventional battleship.), the effective counter to a CSG is unlikely another CSG, but instead a whole range of asymmetrical means such as strikes against its rear-echelon fast combat support ships (AOEs), land-based airpower or submarine warfare. Moreover, one need not send the aircraft carrier to the bottom, resulting in massive loss of lives of those on board, to neutralize the combat effectiveness of a CSG.

Even if Chinese aircraft carriers were to become targets of the USN’s CSG, it would still be an unequal encounter for the PLAN, facing much more experienced USN CSGs with superior sortie rate and integrated defense. In such an encounter, the US Navy could inflict sufficient damage to incapacitate a Chinese aircraft carrier without actually sinking it. The best way to render an aircraft carrier useless is to limit the effectiveness of its air wing. Liaoning’s air wing is in this respect very modest totaling 30 J-15s fighter jets with compromised range, endurance and armament resulting from a lack of catapult launch systems. This number will most likely be higher for Liaoning’s successors, but the sortie generation rate accumulated through operational experience will take a lot longer to equalize. In comparison, Nimitz and Ford-class supercarriers typically carry 70-80 fixed wing aircraft and helicopters and their designs are much more flexible to accommodate various mission requirements.

Furthermore, the employment of a CSG in an open confrontation would run contrary to the tactics and culture consistently displayed by a sea-denial mindset influenced by the tradition of people’s war that informs so much of the CCP’s naval strategy (p. 37), prominently displayed during the Battle of Dongshan on 6 Aug 1965, where 11 PLAN torpedo boats and 4 patrol boats sunk 2 Taiwanese capital ships in 3 consecutive waves, resulting in 171 missing and 31 deaths, including the commander of the ROCN Second Fleet. The PLAN’s efforts towards becoming a Blue-Water Navy have undoubtedly changed its tactical mindset, but even then deployment of a Chinese aircraft carrier against Taiwan (and presumably against the USN) does not offer advantages that would outweigh the potential costs. If deployed outside of the A2AD protective cover, a Chinese CSG would be too weak to counter its US counterpart, and when deployed within A2AD cover, its capabilities are largely redundant.

Moreover, while the debate focuses on the political significance of sinking a US aircraft carrier, Beijing itself could ill-afford the political consequences of its CSG rendered impotent during combat in or close to the Taiwan Strait where potential adversaries such as Taiwan’s recently introduced Tuo Jiang class missile corvette could fully exploit its weaknesses. Indeed, should China deploy its CSG near Taiwan as a part of combat operations, USN would not need to fire a single shot and China’s capital ship could still end-up incapacitated or sunk. Taiwan’s sea and land-based anti-ship missiles represent a reverse A2AD significant challenge for China.

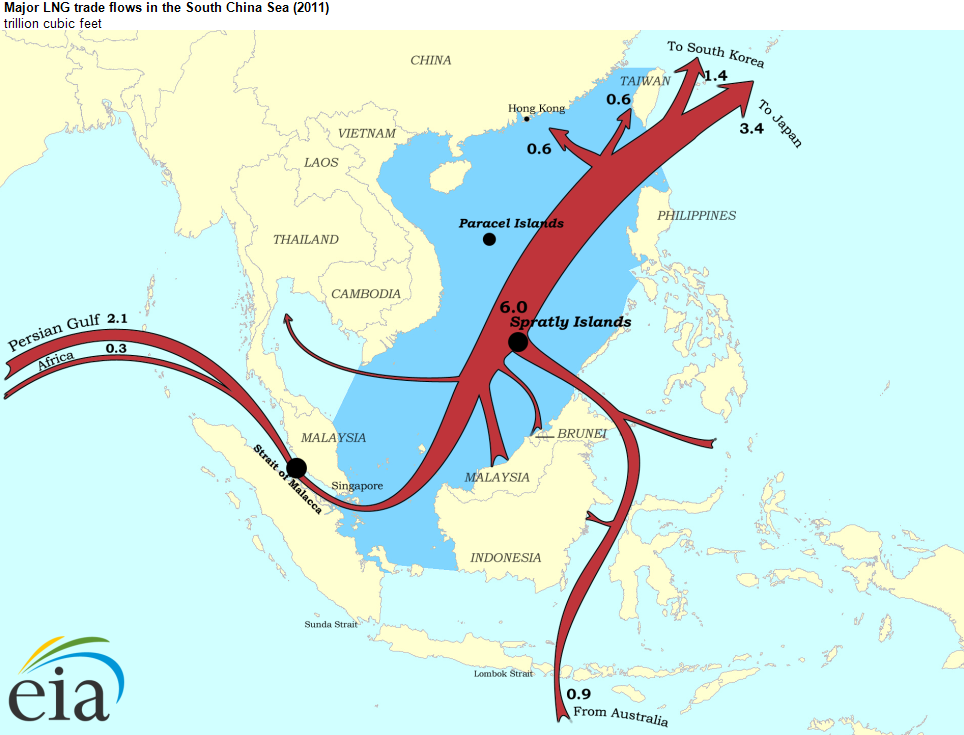

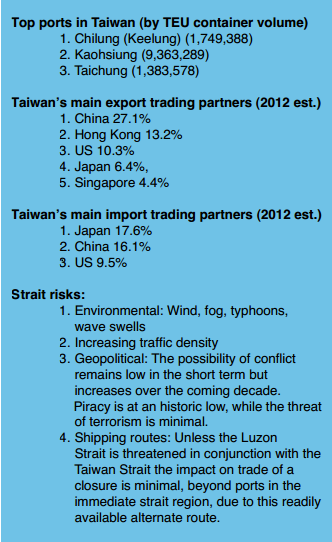

Hence it is reasonable to conclude that the Chinese acquisition of the Liaoning and the further expansion of the Chinese aircraft carrier fleet, while significant, has very little direct impact on a potential crisis deployment in the Taiwan Strait. Instead one should look toward the prestige factor of presenting itself as a Blue Water Navy and a CSG’s value in prosecuting the territorial ambitions displayed by the Chinese government in recent times, e.g. in the South China Sea or the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands, where Chinese land-based airpower does not enjoy the same advantage as in the case of Taiwan-related contingency.

In a potential crisis across the Taiwan Strait, the PLAN’s goal would be better served through a deterrence formed by a combination of guided missiles destroyer-led surface action groups, land-based airpower utilizing supersonic ASMs coupled with over the horizon (OTH) targeting, and high-end attack submarines rivaling the low noise level of even US Seawolf-class SSNs. All of this could successfully prevent US reinforcements from accessing littoral regions of the theater (A2) and impede their movement along the First Island Chain (AD).

Aircraft carriers will maintain its role as a blue water force projector in the foreseeable future. Indeed, they are indispensable for a global sea-control navy tasked with missions to protect sea lines of communication. But the carrier battle groups were never meant to physically present itself in an environment similar to the Taiwan Strait. Granted, ASMs and submarines are problem on the open seas too but any potential opponents would be limited by the storage capacity of their onboard ordnance, with PLAN having limited ability of underway replenishment. In other words, open sea offers no advantage of a compressed engagement battlespace that littoral contestant such as China possesses against the limited range of present day CSG, bearing in mind that as China’s A2AD capabilities make it difficult for US Navy CSGs, PLAN’s own aircraft carrier faces the very same risk from the its neighbors, Taiwan included.

Michal Thim is a Ph.D. candidate in the Taiwan Studies Program at the China Policy Institute (CPI), University of Nottingham, a member of The Center for International Maritime Security, an Asia-Pacific Desk Contributing Analyst for Wikistrat and a Research Fellow at the Prague-based think-tank Association for International Affairs. Michal tweets @michalthim.

Liao Yen-Fan is Taipei-based defense analyst specializing in airpower and Taiwanese military. He can be reached for comment at [email protected].