By LT Jeff Vandenengel, USN

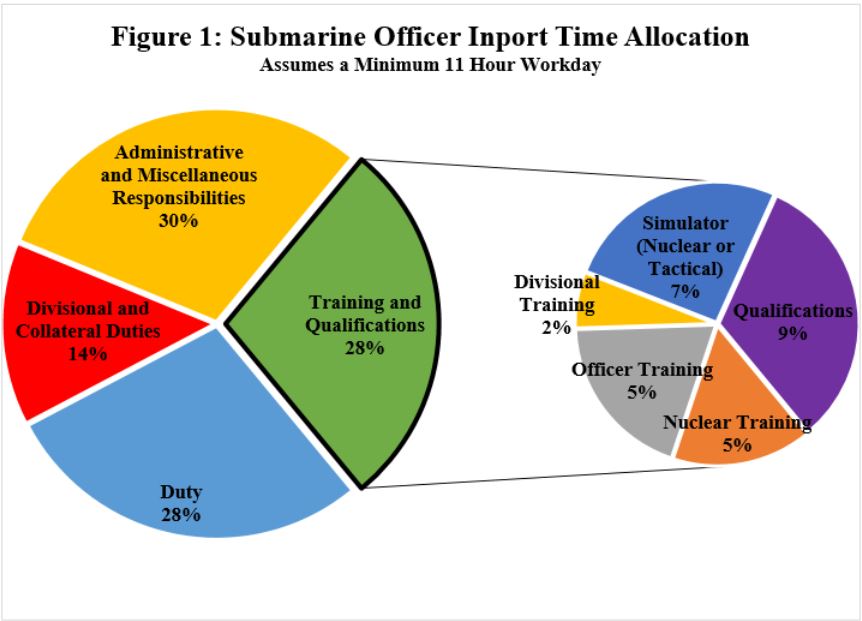

This two-part article focuses on how the submarine force can more effectively prepare for safe deployments in peace and combat-effective operations in war. Part One focused on time constraints affecting the submarine fleet’s ability to focus on training. Part Two focuses on other problems that arise once submariners find time to train, both in their homeports and while deployed. Those problems include limited trainer (simulator) availability and extensive administrative burdens placed on deployed submarines.

Factor 2: Limited Training Resources

“My expectation is that commanders will give high priority to training and developing their junior leaders and teams. No commander can do very wrong if you are training and empowering your junior leaders.”1 – ADM John M. Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations Message on Navy-Wide Operational Pause

As discussed in Part One, time constraints are the first factor limiting submariners’ ability to effectively train for at-sea operations. However, when they fight through that obstacle and allocate time to dedicated in-port practice, scarce trainer resources prove to be another hurdle.

The Navy’s various nuclear, ship-handling, navigation, and tactical trainers are extremely important for submarine training. During long in-port periods, they are the best way to keep officers’ and sailors’ operational skills sharp and to prepare junior personnel for new roles. Trainers also allow submariners to practice evolutions and drills—such as large nuclear casualties, complex wartime engagements, or dangerous ship-handling maneuvers—that cannot be completed at sea, either due to the inability to effectively simulate the scenario or safety concerns. These trainers are also the best way to safely let officers and sailors fail and learn from their mistakes, seldom an option at sea.

Build More Shore-Based Trainers

Submarine force trainers are constantly in high demand. After all the required sessions are scheduled, such as tactical evaluations, courses for boats, schools for sailors and officers, re-examinations, and midshipmen and VIP tours, there are rarely slots available that coincide with a boat’s free time. Busy homeports such as Pearl Harbor, where there are twenty-one submarines sharing very limited trainer time, face an even greater challenge.2 As a result, some Pearl Harbor and Bangor submarines sail to San Diego to use their trainers for tactical evaluations, forcing them to expend some of their hull and reactor life and lose more time with their families simply because there are not enough trainers available in their homeport.

In his Comprehensive Review of recent surface fleet collisions and mishaps, Admiral Philip Davidson cited multiple deficiencies in shore-based team training.3 The submarine fleet should minimize the risk of similar mishaps by building more trainers. These trainers, covering scenarios such as surfaced ship driving, nuclear operations, and submerged warfighting, will cost money. They will cost significantly less than the estimated $600 million required to repair USS Fitzgerald and USS McCain after their collisions.4

Hire More Submarine Greybeards

Even if the submarine fleet does not build any additional shore-based trainers, it should hire more “Tactical Advisors,” or “Greybeards,” to staff them. Greybeards are retired submarine COs attached to submarine homeport training centers. They use their knowledge and experience to provide outstanding senior-level feedback, training, and evaluation to boats with a focus on tactics and contact management.

The problem is that the Greybeards are strapped for time and rarely available. Most submarine homeports have just one Greybeard who must cover all submarine evaluations. As a result, they are generally not available to assist a boat with preparations for these evaluations or for deployment. Even in San Diego, which has just a few boats, the Greybeard is often unavailable because he is travelling to other busier homeports to support their evaluations.

To better use these excellent resources, the submarine fleet should achieve a five-to-one ratio of submarines to Greybeards. This would make them more available for submarine training sessions, courses, and schools. Greybeards would also be available to come down to the waterfront and give requested training, drawing on their vast experience and available time to produce a quality product. Every year, highly successful submarine captains are leaving command, and many of them will go on to retirement or jobs where the Navy is unable to take advantage of their tactical expertise. Hiring a small fraction of these officers as additional Greybeards would produce a markedly safer and tactically proficient force.

Many college courses are taught by very capable graduate teaching assistants (TAs). Although they do a good job at educating their students, TAs are rarely as capable as a full professor due to their relative lack of experience and knowledge. Similarly, most submarine trainer feedback comes from JOs and sailors on their shore duty, dedicated men and women who—through no fault of their own—are not as effective at training as Greybeards. The Navy should hire more Greybeards—professors with a focus in at-sea operations and combat.

Factor 3: Administrative Burdens While Deployed

“We need to get back to owning our jobs, concentrating on the operational excellence piece of what our Navy is about, and reducing these administrative distractions that pull us away from that.”5 – ADM John M. Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations Online All Hands Call

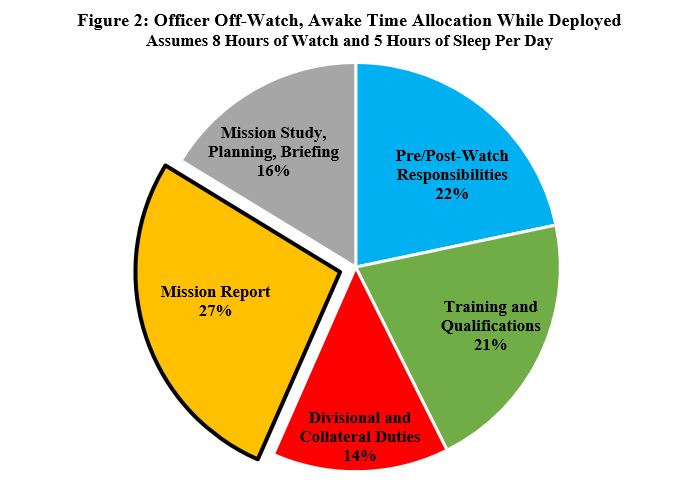

Despite the challenges of Factor 1 (limited training time) and Factor 2 (limited training resources), submarines are fighting through these limitations to safely depart for deployment. While deployed, most off-watch time should be spent studying tactics and preparing for upcoming operations. Instead, as shown in Figure 2, officers are spending approximately 2.5 hours each day—27 percent of their awake, off-watch hours—writing and editing a massive report detailing the ship’s operations.

While deployed, submarines typically employ four officers in control: an OOD, Junior OOD (JOOD), Contact Manager (CM), and Junior Officer the Watch (JOOW). While the OOD, JOOD, and CM fight to keep the ship safe and execute the mission, the JOOW’s sole responsibility is to record everything that the ship is doing. Even though virtually all the required data is already automatically recorded on numerous other systems, the JOOW is required to manually type everything into Microsoft Word. After eight hours of this on watch, the OOD, JOOD, CM, and JOOW all spend several hours refining the document. Some of this time is spent clarifying the ship’s operations and providing important commentary for the report’s end users, but most of the time is spent transcribing data from other systems, fixing grammar, and adjusting formatting. Once complete, the XO and then CO carefully review the consolidated product, often sending it back to the OOD for clarification or corrections and to fix incorrectly transcribed data.

The opportunity cost of the mission report is a degree of submarine safety and warfighting readiness. A typical wardroom, while off-watch, will devote roughly 4,000 officer-hours to the mission report throughout a deployment.6 While they are working on writing, formatting, and editing the report, these officers are not studying tactical references, analyzing external information as it comes in, or preparing the boat for the next operation, forcing them to often sacrifice sleep to complete this task. Deployed submarine officers are generally in a perpetual state of near-exhaustion, and the mission report is the primary reason for that lack of rest. In the surface fleet’s Comprehensive Review, Admiral Davidson cited lack of sleep as a contributing factor to both the USS Fitzgerald and USS McCain collisions.7 The mission report’s massive requirements and lack of automation make it the epitome of an “Administrative Distraction” keeping submariners from focusing on the safe, tactical employment of their warship.8

Consider the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) response to a hypothetical commercial airline using a similar process. In this airline, the pilot, co-pilot, and navigator focus on safely flying to the destination while a fourth flight officer records every change in course, speed, and altitude, every other plane flying by, and countless other details despite the Black Box recording the same data simultaneously. When the plane lands after a long eight-hour flight, the pilot, co-pilot, and navigator then spend several hours reading and editing the document before getting five or six hours of sleep and doing it all over again the next day. The FAA would likely deem that a terrible and unsafe use of time and demand an automated alternative.

The mission report also has important implications for submarine force manning. Submarines do not have enough officers to support a three-section watch-bill with the JOOW. As a result, when detailers send additional officers to boats entering shipyard availabilities, many of those officers get dispatched to deploying units to fill the role of JOOW. Serving as JOOW, essentially acting as a secretary for ship’s operations, negatively affects their ability to complete required nuclear and tactical qualifications, meaning that each wardroom is less knowledgeable and that the submarine fleet needs to recruit and train more officers, a constant struggle.

Despite the substantial effort that its officers are devoting to the mission report, the submarine fleet gains little benefit from the final product. Other boats’ reports could be valuable tools for wardrooms preparing for an upcoming mission, but instead the reports’ size, quantity, and tediousness makes it very difficult to pull out useful information or lessons, limiting the reports’ utility.

Fortunately, the mission report problem could be easily solved. Most of the data the JOOW writes is already recorded by other systems, so the submarine fleet simply needs to devote resources to develop and approve an automated program to combine these sources. Not only would this help the officers, but it would yield a better final product; there would be fewer formatting and transcription errors and the wardroom would have more time to add meaningful commentary. Alternatively, all that data could be left on those separate systems and only be pulled and consolidated if needed, such as during an event of interest. Factor 1 (massive time obligations) discussed how many of the submarine force’s tasks are important to complete, but could be better done by a supporting command. This same approach could be used to solve the mission report dilemma; the submarine fleet could leave all that data on those separate systems and have shore-based end users pull and analyze what they desire. This would allow them to complete this time-consuming administration with staff officers or civilians in a safe office environment instead of demanding unrestricted line officers complete this work at sea while also attempting to keep their ship safe and combat ready.

On August 2, 1945, Commander Eugene Fluckey completed USS Barb’s twelfth war patrol. During this patrol, Commander Fluckey sank 11,000 tons of shipping, conducted the first-ever submarine-launched rocket attack, and destroyed a train, yet submitted a War Patrol Report of just 66 pages.9 Today, our submarines can complete a mission of the same duration without ever encountering a single foreign warship or submarine and still be expected to type and submit a report exceeding 1,000 pages. Just because Commander Fluckey could not use automation and had to manually type his report does not mean today’s submarine force needs to do the same.

Putting Warfighting First

Today’s Navy is faced with serious yet surmountable challenges. The deadly incidents involving Fitzgerald and McCain revealed a hard-pressed fleet fighting to safely operate at sea at the same time that foreign navies rapidly improve their technologies and capabilities. In response, the Navy’s leadership is rightfully charging the fleet with ensuring that warfighting comes first. Yet many submariners, swamped with watch, administration, and collateral duties, are responding with, “Hooyah, but how?”

Consolidated Recommendations

The Navy has devoted incredible time and energy to designing, building, maintaining, and manning its submarine fleet. To maximize that return on investment and ensure those submarines are ready for war, the Navy should address three key factors using the following solutions:

- Reduce time obligations on the officers and crew

- Allow non-ship’s force officers or CPOs to augment EDO watch-bills

- Allow non-ship’s force officers or CPOs to augment SDO watch-bills

- Allow non-ship’s force sailors to augment topside security watches

- Outsource maintenance procedure development and approval

- Shift some QAO responsibilities to regional QA offices

- Remove the requirement for SSNs to man Scuba Diving Divisions

- Shift security clearance investigation responsibilities to squadron SSOs

- Shift in-port Radiation Health Responsibilities to squadrons

- Minimize submarines’ Cryptologic Security Management responsibilities

- Outsource some duties such as manual page updates and gage calibration

- Conduct a holistic review and reduction in submariners’ time commitments

- Improve shore-based training resources

- Build more shore-based team trainers

- Hire more submarine Greybeards

- Reduce deployment administrative burdens

- Reduce the data required in the mission report

- Automate the mission report as much as possible

- Shift some mission report responsibilities to civilians or restricted line officers

- Reduce the number of required reports and naval messages while deployed

If the Navy can adopt these recommendations, it will result in a significantly safer and more combat-effective force. Officers and sailors with significantly higher levels of knowledge will form experienced teams aided by deep benches. Those teams will form the backbone of a truly professional naval force, yielding a fleet made stronger through personnel and administrative changes alone.

As with any profession, there is an abundance of material to study in the submarine force. Mastering topics such as nuclear systems, Nautical Rules of the Road, advanced weapon systems, coordinated fleet tactics, ship maneuvering characteristics, and submerged navigation requires a great deal of time and study. A refocused submarine fleet will have more bandwidth to attack these topics. They could even expand their study into topics such as naval history or geopolitics, which are currently not required but would better the officers and crew. A fleet protected from countless administrative burdens will be able to better study the numerous intelligence products, tactical manuals, lessons learned, and order-of-battle analyses that are currently only being skimmed or skipped altogether due to lack of time.10

Those more knowledgeable officers and sailors would also have more time to train together as a team. Instead of rushing to train watch-sections for the next upcoming inspection, submarines would have the time and resources to maintain a constant strain on learning and practicing. That constant strain would allow teams to try new tactics and approaches—and potentially fail—and still be better prepared for the next challenge.

A submarine force with a higher level of knowledge and better-tested teams will be comprised of true naval professionals instead of jacks of all trades. Doctors, baseball players, engineers, and lawyers all require incredible amounts of time focused on learning and practicing their trade; why do we think the naval professional is any different?

Five decades ago, poor maintenance practices likely led to the loss of USS Thresher and USS Scorpion. The submarine force attacked the problem, greatly improving its boats’ physical conditions through processes such as the SUBSAFE Program.11 In contrast, personnel and training failures were the primary cause of more recent mishaps, including those of USS Hartford, USS Montpelier, USS Jacksonville, USS Fitzgerald, and USS McCain. Our weakness appears to have shifted from equipment to training.

Today’s submarine operations are succeeding not because of robust training programs but rather due to the extremely high-quality people onboard and just-in-time training. That is not a resilient model, and it will invariably lead to failure. Fortunately, there are options to solve the problem before it leads to more fatal mishaps, the loss of an entire boat, or subpar performance in conflict. Those solutions would produce a force ready to safely take their ships to sea in peace, and ready to expertly wield them in time of war.

The Navy’s leaders have directed the fleet to make combat preparations its primary concern. The officers and sailors on the deckplates are wholly committed to that goal. Reduced time demands, increased training resources, and fewer deployed administrative requirements would make that warfighting focus a reality.

LT Vandenengel is the Weapons Officer on USS Alexandria (SSN 757). He developed this paper with a working group of submarine officers. The views expressed here are those of the author alone and do not represent those of the Department of Defense. You can reach him at jeff.vandenengel@gmail.com.

Endnotes

[1] Admiral John M. Richardson, USN. “CNO Richardson Message on Navy Operational Pause,” USNI News, October 6, 2017, https://news.usni.org/2017/10/06/cno-richardson-message-navy-operational-pause.

[2] “SUBPAC Commands,” Submarine Force Pacific, accessed November 11, 2017, http://www.csp.navy.mil/subpac-commands/.

[3] Admiral Philip S. Davidson, USN. “Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents.” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Fleet Forces Command, October 26, 2017), 63.

[4] Sam LaGrone “USS Fitzgerald Repair Will Take More Than a Year; USS John M. McCain Fix Could be Shorter,” USNI News, September 20, 2017, https://news.usni.org/2017/09/20/uss-fitzgerald-repair-will-take-year-uss-john-s-mccain-fix-shorter.

[5] Admiral John M. Richardson, USN and Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy Steven Giordano, USN. “Facebook Live All Hands Call: ‘Administrative Distractions.’” August 30, 2017. YouTube video, 1:33. Posted September 4, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W2QTpnaeqiM.

[6] Estimating each section’s four officers spending 2.5 hours on the mission report each day that it is being recorded, with the CO and XO working on it one hour and two hours per day, respectively. This time is in addition to the roughly 3,000 officer-hours that JOOWs will spend writing the mission report while on watch.

[7] Admiral Philip S. Davidson, USN. “Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents.” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Fleet Forces Command, October 26, 2017), 38.

[8] Rear Admiral Herman Shelanksi, USN. “Taking Action-Reducing Administrative Distractions Implementing Change in Phase III,” Navy Live, September 25, 2013, http://navylive.dodlive.mil/2013/09/25/taking-action-reducing-adminstrative-distractions-implementing-change-in-phase-iii/.

[9] Commander Eugene Fluckey, USN. “USS Barb (SS 220), Report of Twelfth War Patrol.” (Midway Island, August 2, 1945), 97-163, https://www.scribd.com/document/175964974/SS-220-Barb-Part2.

[10] Surface ships can be subjected to as many as 238 separate inspections, certifications, and assist visits per 36-month period, all requiring officer time investment, and the submarine fleet is likely subject to a comparable number. Admiral Philip S. Davidson, USN. “Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents.” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Fleet Forces Command, October 26, 2017), 78.

[11] Sam LaGrone “After Thresher: How the Navy Made Subs Safer,” USNI News, April 4, 2013, https://news.usni.org/2013/04/04/after-thresher-how-the-navy-made-subs-safer.

Featured Image: ARABIAN SEA (April 22, 2012) The Los Angeles-class attack submarine USS Pittsburgh (SSN 720) transits the Arabian Sea. Pittsburgh is deployed to the 5th Fleet area of responsibility. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Tim D. Godbee/Released)