By Bill Glenney

Articles Due: March 5, 2018

Week Dates: March 12–March 16, 2018

Article Length: 1000-3000 Words

Submit to: Nextwar@cimsec.org

The U.S. Naval War College’s Institute for Future Warfare Studies is partnering with CIMSEC to solicit articles putting forth concepts for warfare on and from the seabed as part of the larger maritime battle.

While the broad matter of economics and sea lines of communications should drive a national and Navy interest in securing the seabed, the transformative nature of warfare on and from the seabed should capture the imagination and be of concern to the Navy.

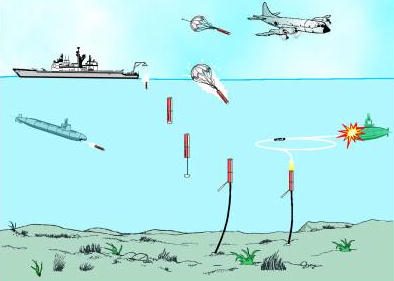

Systems operating from the ocean seabed – to include unmanned systems, mini-submersibles, smart mines, special forces, and others – will one day be deployed against surface, air, and land systems and not just traditional undersea forces – adding yet another dimension to cross- or multi-domain warfare. Navies will be forced to consider not only the role of the seabed and undersea forces in seabed combat, but also how effects from the seabed can shape the behavior of forces on the surface, in the air, and on land.

At its heart, the assumption of U. S. undersea supremacy based on owning the top 1,000 feet of the water column will become invalid, ineffective, and wrong, just as aviators once assumed air supremacy was assured from owning airspace above 30,000 feet. Similarly, the Submarine Force will have to abandon its traditional assumptions about how operating within the undersea domain enhances survivability. Seabed threats may mean the U.S. Navy could have to fight its way out of CONUS home waters before it could project power abroad, and allow adversaries to persistently threaten the U.S. Navy’s flanks and rear support areas. Warfare under the sea may come to look more like tunnel warfare of World War One or suppression of enemy air defenses in Syria than ASW of the Cold War.

The seabed has already long suffered from neglect by the U. S. Navy. For example, modern sea mines can already project power from the seabed with little to no warning, but since the end of the Cold War the Navy and the Submarine Force “whistled past the graveyard” and routinely dismissed the threat from sea mines out of hand. This neglect was reflected in continual lack of substantive funding related to USN mine warfare capabilities and associated tactical development. This trend continued even as more U.S. warships were sunk or damaged in the aftermath of WWII by sea mines than by any other weapon while potential adversaries have tens of thousands of mines. Weapons on the seabed exacerbate the problem even more.

Nations and commercial entities can be expected to routinely map seabed terrain to support their interests and activities. Available seafloor bathymetry may become comparable to a typical topographic map available in hard copy. This level of detail will facilitate planning for and the placement of systems on the ocean floor, especially with a focus on ensuring they could not be readily detected or attacked. Weapons and supplies could be hidden in seabed caves, trenches, and other geographical features within the complicated seabed landscape.

The threat posed by systems operating from this part of the maritime environment will only grow with technological change and proliferation. The impending proliferation of commercially-developed undersea and seabed systems will make these systems readily available to anyone with even a modest amount of funding. These systems had long ago departed being a resource only for a rich nation-state or billionaires intent on finding the resting place of sunken ships.

Authors are invited to write on the tactical and operational challenges, and potential solutions, that may emerge as maritime warfare expands onto the seabed. How can the Navy’s future force adapt to this coming reality? Authors should send their submissions to Nextwar@cimsec.org.

Professor William G. Glenney, IV, is a researcher in the Institute for Future Warfare Studies at the U. S. Naval War College.

The views presented here are personal and do not reflect official positions of the Naval War College, DON or DOD.

Featured Image: Undersea submersible (Brian Skerry, National Geographic Creative)