This publication was originally featured on Bharat Shakti and is republished with permission. It may be read in its original form here.

By Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan AVSM & Bar, VSM, IN (Ret.)

Editor-in-Chief’s Note

Part I of this two-part article introduced the geoeconomic and geostrategic imperatives that shape China’s geopolitical drives. It also presented the overarching concept of “reach” as an aid to understanding the international import of China’s military strategy. Read Part I here.

In this second and concluding part of the article series the author explores Chinese strategic intent and its ramifications. The article provides an account of the naval facilities China is promoting or constructing on disputed islands among littoral states of the Indian Ocean; assesses China’s economic linkages with African nations; and projects the growth curve of the Chinese Navy, all of which are important to keep in view while analyzing the trajectory of Chinese geo-strategic intent.

By emphasizing the factor of temporal strategic-surprise (in contrast to spatial surprise), the author offers clues to understanding the links between China’s military strategy and her geopolitical international game-moves as they are being played out within a predominantly maritime paradigm. As in the famous Chinese game of Go—perhaps a more apt analogy than chess—the People’s Republic is putting in place the pieces that will shape her desired geopolitical space. The author explores the spatial and temporal dimensions of the Chinese strategy and the related vulnerabilities of the opposing Indian establishment.

In his 2006 dissertation written at the US Army War College then-Lt. Col Christopher J. Pehrson, USAF, termed the Chinese geostrategy the “String of Pearls.” This expression, first used in January 2005 in a report to U.S. military officials prepared by the U.S. consulting firm of Booz Allen Hamilton, caught the attention of the world’s imagination. Pehrson posited China as a slightly sinister, rising global power, playing a new strategic game, as grandiose in its concept, formulation and execution as the “Great Game” of the 19th century. Despite vehement and frequent denials by Chinese leadership of any such geostrategic machinations designed at the accumulation of enhanced geopolitical and geoeconomic power and influence, the expression rapidly embedded itself into mainstream consciousness.

As a net result, for over a decade, China has chafed under the opprobrium heaped upon it for a concept that (to be fair) it had never once articulated by the state. However, in a brilliant rebranding exercise by Beijing in 2014, the world’s attention is being increasingly drawn away from the negative connotations associated with the phrase String of Pearls and towards the more benign-sounding 21st century Maritime Silk Route Economic Belt, also known as “One Road, One Belt.” This presents an alternative expression, while it nevertheless covers essentially the very same geostrategic maritime game-plays that Colonel Pehrson explained a decade ago. The new expression emphasizes transregional inclusiveness and evokes the romance of a shared pan-Asian history with the implied promise of a reestablishment of the economic prosperity that the Asian continent’s major civilizational and socio-cultural entities, namely China and India, enjoyed until the 18th century.

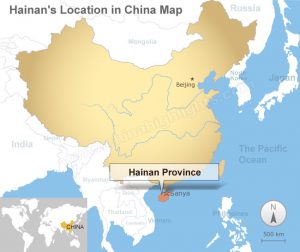

Each “pearl” in the String of Pearls construct—or in more contemporary parlance, each “node” along the Maritime Silk Route—is a link in a chain of Chinese geopolitical and geostrategic influence. For example, Hainan Island, with its recently upgraded military facilities and sheltered submarine base, is a pearl/node.

It is by no means necessary for a line joining these pearls/nodes to encompass mainland China in one of the concentric ripples typified by the Island Chains strategy. In fact, since the Maritime Silk Route is a true maritime construct, it is highly unlikely that the nodes would do so.

Other pearls/nodes include the recent creation of artificial islands in the Paracel and Spratly islands incorporating, inter alia, the ongoing construction/upgrade of airstrips on Woody Island—located in the Paracel Islands, some 300 nm east of Vietnam—as also on Mischief Reef and Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly Islands. Additional pearls/nodes have been obtained through Chinese investments in Cambodia and China’s continuing interest in Thailand’s Isthmus of Kra.

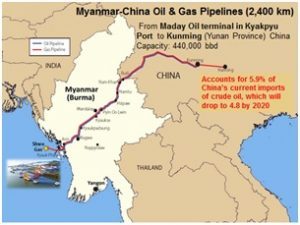

China’s development of major maritime infrastructure abroad—the container terminal in Chittagong, Bangladesh; the Maday crude oil terminal in Myanmar’s Kyakpyu port; the development of ports such as Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Gwadar in Pakistan, Bagamoyo in Tanzania, Beira in Mozambique, Walvis Bay in Namibia, Kribi in Cameroon, the Djibouti Multipurpose Port (DMP), and the offer to even develop Chabahar in Iran (checkmated by a belated but vigorous Indian initiative), along with the successful establishment of a military (naval) base in Djibouti—all constitute yet more pearls/nodes. The development of an atoll in the Seychelles, oil infrastructure projects in Sudan and Angola, and the financing of newly discovered massive gas finds in offshore areas of Mozambique, Tanzania and the Comoros, are similarly recently acquired pearls/nodes. Even Australia yields a pearl/node, as does South Africa, thanks to Chinese strategic investment in mining in general and uranium-mining companies in particular, in both countries.

From an Indian perspective, China’s new strategic maritime-constructs (by whichever name) are simultaneously operative on a number of levels, several of which are predominantly economic in nature and portend nothing more than fierce competition. At the geostrategic level, however, the economy is at its apex and is China’s and India’s greatest strength and greatest vulnerability, at the same time; therefore, the economy is the centerpiece of the policy and strategy of both countries. This is precisely why, as the geographical competition space between India and China coincide in the Indian Ocean, there is a very real possibility of competition transforming into conflict, particularly as the adverse effects of climate change on resources and the available land area becomes increasingly more evident.

“Reach” has both spatial and temporal dimensions. The spatial facets of China’s geopolitical moves are evident, as illustrated in the preceding String of Pearls discussion. It is critical for India’s geopolitical and military analysts to also understand the temporal facets of this construct. The terms short term, medium term and long term are seldom used with any degree of digital precision. A nation tends to keep its collective “eye on the ball” in the short term and, by corollary, tends to assign far less urgency to something that is assigned to the long term. This ill-defined differentiation is how strategic surprise may be achieved in the temporal plane. For instance, in China, the short term generally implies 30 to 50 years. This is an epoch that is far in excess of what in India passes as the long term. Consequently, India fails to pay as close attention to developments in China as she might have were the developments to unfold in a duration corresponding to India’s own short term of 2-5 years. This distinction permits China to achieve strategic surprise, and this is as true of military strategy as it is of grand strategy and geoeconomics.

On the one hand, it should be remembered that these strategic constructs are not only about maritime infrastructure projects, involving the construction of ports, pipelines and airfields, though these developments constitute their most obvious and visibly worrisome manifestation. The strategy is equally about new, renewed or reinvigorated geopolitical and diplomatic ties between the People’s Republic of China and nation states across a very wide geographical swath (including the African littoral and the island nations of both the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean). On the other hand, China’s strategic maritime constructs have some important military spin-offs, which closely align to the furtherance of geostrategic reach. Thus, by developing friendly ports of call (if not bases), facilities and favorable economic dependencies in the various pearls/nodes, the logistics involved in the event of an engagement in maritime power-projection are greatly eased.

Supplementing the pearls/nodes are the Chinese Navy’s five impressive stores/ammunition supply ships of the Dayun Class (Type 904) and six underway replenishment tankers of the Qiandaohu Class (Type 903A). In addition, China requires ground control stations to meet her satellite-based needs of real-time surveillance. Unlike the United States, China simply does not have adequate ground control/tracking stations within the Indian Ocean to affect requisite ground control and real-time downlinking of her remote-sensing satellites. This forces her to deploy a number of ships (the Yuanwang Class) for this purpose. These constitute a severe vulnerability that China certainly needs to overcome. One way to do so is to establish infrastructure and acceptability along the IOR island states and along the East African littoral, as China is currently attempting to do.

The principal lack in the Chinese strategy to provide military substance to the country’s geoeconomic and geostrategic reach comes in the form of integral air power through aircraft carriers. China is rapidly learning that while one can buy or build an aircraft carrier in only a couple of years, it takes many more years to develop the human, material, logistic and doctrinal skills required for competent and battle worthy carrier-borne aviation. For nearly a decade now, China has demonstrated her ability to sustain persistent military (naval) presence in the Indian Ocean—albeit in a low threat environment. Combat capability is, of course, quite different from mere presence or even the ability to maintain anti-piracy forces, since the threat posed to China by disparate groups of poorly armed, equipped and led pirates can hardly be equated with that posed by a powerful and competent military adversary in times of conflict.

Despite the impressive growth of the Chinese Navy and the vigor of the Chinese military strategy, China may not, in the immediate present, have the combat capability to deploy for any extended period of time in support of its geoeconomic and geostrategic reach were they to be militarily contested by a major navy. However, as James Holmes points out, if India were to continue to cite shortfalls in current Chinese capability and conclude that it will take the PLA Navy at least fifteen years to station a standing, battle worthy naval squadron in the Indian Ocean, this would lull Indians into underplaying Chinese determination and the speed of that country’s military growth. This would carry the very real consequent possibility of India suffering a massive strategic surprise. Is that something that India can afford?

Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan retired as Commandant of the Indian Naval Academy at Ezhimala. He is an alumnus of the prestigious National Defence College.

However, to meet the ever-growing demand for mineral

However, to meet the ever-growing demand for mineral  An ever-increasing demand for energy fuels China and India’s economic growth. Although the share of coal is still the largest in the energy-basket of both countries, oil consumption is growing so rapidly that it is driving the foreign policy and security perspectives of both China and India. In 1985, China was East Asia’s largest exporter of oil. In 1993, China became a net importer, and in 2015, she became the largest importer of crude oil on the planet. By April 2015, China was importing a staggering 7.4 million barrels per day (bbd) and by 2020, China will be importing an estimated 9.2 million bbd of crude-oil.

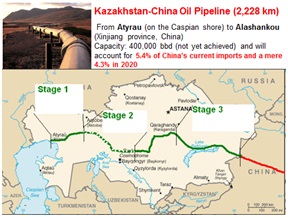

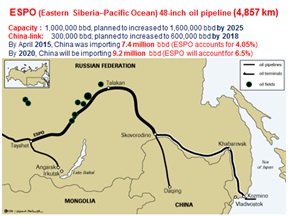

An ever-increasing demand for energy fuels China and India’s economic growth. Although the share of coal is still the largest in the energy-basket of both countries, oil consumption is growing so rapidly that it is driving the foreign policy and security perspectives of both China and India. In 1985, China was East Asia’s largest exporter of oil. In 1993, China became a net importer, and in 2015, she became the largest importer of crude oil on the planet. By April 2015, China was importing a staggering 7.4 million barrels per day (bbd) and by 2020, China will be importing an estimated 9.2 million bbd of crude-oil. For all the marvelous engineering, the three main crude oil pipelines into China (the Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean pipeline (ESPO), the Kazakhstan-China oil Pipeline and the Myanmar-China oil pipeline), taken in aggregate, cater for a mere 15% of China’s crude oil imports. Almost all of the enormous quantity of crude oil that China imports either lies within or must travel across the Indian Ocean and must transit one or more of the chokepoints that connect the Indian and the Pacific Oceans. These are: the Malacca Strait, the Sunda Strait, the Lombok strait, and the Ombai-Wetar strait. Of these, the Malacca Strait and the Lombok Strait of are particular importance to China and constitute what Chinese leaders term the “Malacca Dilemma.”

For all the marvelous engineering, the three main crude oil pipelines into China (the Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean pipeline (ESPO), the Kazakhstan-China oil Pipeline and the Myanmar-China oil pipeline), taken in aggregate, cater for a mere 15% of China’s crude oil imports. Almost all of the enormous quantity of crude oil that China imports either lies within or must travel across the Indian Ocean and must transit one or more of the chokepoints that connect the Indian and the Pacific Oceans. These are: the Malacca Strait, the Sunda Strait, the Lombok strait, and the Ombai-Wetar strait. Of these, the Malacca Strait and the Lombok Strait of are particular importance to China and constitute what Chinese leaders term the “Malacca Dilemma.”