By Matt McLaughlin

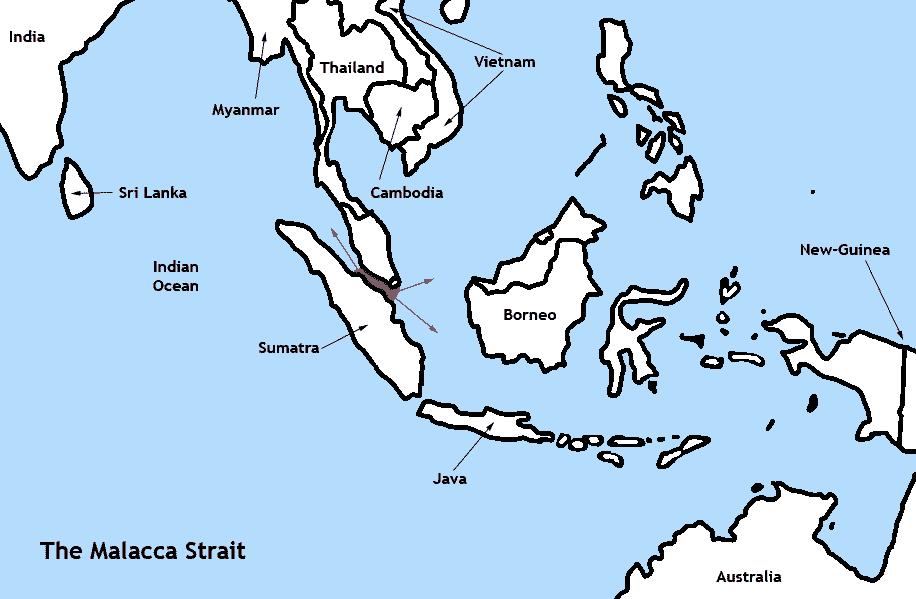

In the opening years of the century, fear of piracy permeated the Strait of Malacca. Every few days, it seemed, there was another boarding, another theft, another hijacking. Merchant sailors, already leery of the narrow sea lanes, were doubly anxious over the identity of the brigands’ next target – could they be next? And, most remarkably, this was not the Eighteenth Century, but the Twenty-First.

It was for the purpose of alleviating this unprofitable tension that the Malacca Strait Patrol (MSP) was established in 2004. Four neighboring states – Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and, in 2008, Thailand – pooled their resources to combat illicit activity in the critical chokepoint on which they all shared coastlines. By 2009, piracy in the area had been so effectively curtailed that the Naval War College Review could justifiably ask if the problem had been solved.1

An observer 600 miles northeast of Malacca would have seen a less harmonious scenario play out, though. In the South China Sea, a different sort of maritime threat challenges the sovereignty of various Southeast Asian states – territorial claims by China. Since as far back as the 1970s,2 various appendages of the People’s Republic of China have been using force, finesse, and everything in between to stake claims to islands (and potential islands) through a wide swath of the South China Sea, in direct opposition to four Southeast Asian claimants – Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam. This behavior continues today.

How were four neighbors able to cooperate concerning one problem but not the other? Is such a cooperative solution unique or is it transferable to other situations?

Three categories of factors generally account for the difference in scenarios: the legal environment, level of effort, and level of risk. This paper will address elements within all three categories, with some that fall under more than one being discussed multiple times.

Legal Environment

It is a time-honored truth that, Jack Sparrow aside, no one likes pirates. They have no constituency, no patron. Stamping out brigandage in its waters is almost by definition a precondition for a state to be considered legitimate. Minimal tears will be spilled if a state apprehends pirates on the high seas.

As a direct result of civilization’s antipathy toward piracy, it is a recognized precept of international law that pirates are stateless. Any state patrolling for pirates is well within its rights to deal with them, via arrest or other means, in accordance with its own law. Counterpiracy operations, in the Strait of Malacca or anywhere else, are on solid legal ground at the broadest level (allowing for some restrictions, perhaps, at the tactical level).

The legal and moral backing described above ensure that international kudos or, at least, an absence of complaints can be expected by MSP participants. Surely it was widely appreciated when Lloyd’s of London ceased listing the Strait of Malacca as a “war risk area” in 2006 as a result of MSP’s actions.3 Recognition such as this is not, strictly speaking, a legal matter. However, in the realm of international law, where precedent and custom are just as important as written treaties, support from peers is critical in ensuring the legitimacy of an action.

Contrast this with the South China Sea. The Southeast Asian nations whose shores it laps are uniformly exasperated, no doubt, with Chinese fishing, island-building, and other nationalist actions in waters well outside China’s own Exclusive Economic Zone. But what to do? Unlike pirates, China has a cheering section. There will be more on this in the Risk section, but suffice it to say, China’s market is big enough (or potentially big enough) that no nation, not even its rivals in the South China Sea, wants to risk losing access to it. As a result, someone can always be found to support the Chinese position, even if holding their nose while doing so.

Legal understandings concerning pirates are more or less universal; not so with territorial disputes, though. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) are generally recognized as legitimate authorities worldwide – but for China, they only apply when they’re convenient. If Chinese interests contrast with international agreement, it will choose to only recognize its own law, whose interpretation of the status of the South China Sea is markedly different from those of its neighbors. Having a conversation among the claimants is most difficult when their points of reference are completely opposed. It is complicated even further when one notes that Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam have their own claims competing against each other – China can say it is simply one more player in an existing dispute. Even fellow members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) found it too costly to support the Philippines in its successful case against Chinese territorial claims at the PCA; the Philippines solicited ASEAN for co-litigants but found none. Despite emerging from arbitration victorious, the Philippines is left to negotiate the way forward on a bilateral basis in an undeniable position of weakness.4

Because concurrence on the end state in the South China Sea is fleeting, international backing for any party to the dispute is lacking. Nations like Japan and the United States can agree that China shouldn’t do what it’s doing – but at the same time, they take no position on how the Sea’s territorial lines should actually look, which is a matter for the four Southeast Asian claimants to determine among themselves. It is hard to oppose one course of action (the Chinese one) without proposing a credible alternative, but that is the only option available to the international community.

Level of Effort

Legal issues aside, very different resources and activities are required for patrolling the Strait of Malacca as opposed to contesting the South China Sea, and those required for counterpiracy lend themselves to international cooperation.

First, counterpiracy is virtually a completely maritime affair. The ships and aircraft of the MSP can patrol international waters, and, occasionally, fly over territorial waters with proper permission, but no one has to set foot on the land of another country. The lack of “boots on ground” makes such cooperation a much simpler affair; it is out of sight and out of mind for most people ashore. It is expensive to maintain and crew equipment that floats and flies, but it is politically palatable in a way that a troop garrison may not be.

The second point is a corollary to the first – while maintaining naval and air forces may not be cheap, neither do they need to be top-of-the-line warfighters, either. The biggest capability such a counterpiracy force offers is simple presence. By being visible in the commons, they can deter piracy without firing a shot or boarding a single vessel. Such a force is achievable even for a middle-income nation like Indonesia. The country may have more-capable forces available (as Singapore certainly does), but they can be sent elsewhere while the low-end constabulary forces monitor the sea lanes.

Outside support is also minimized in conducting the MSP. Members can conduct the mission themselves, as long as their governments provide the proper equipment through international arms sales (such as for P-3 patrol aircraft). The MSP has no involvement from ASEAN, nor is there an ASEAN role in counterpiracy operations anyplace else.5 Strait security does impact all ASEAN members, if for no other reason than to keep maritime insurance premiums down, but it was urgent enough to MSP members in 2004 that they acted on their own accord without waiting for ASEAN to offer collective support through a process that would have undoubtedly taken years. The mission is focused enough that MSP members correctly judged that participation by ASEAN or extra-regional partners was unnecessary.

Lastly, with a non-controversial mission being conducted offshore, direct military-to-military coordination is suitable for the MSP. A headquarters and operations center was built in Singapore6 but, other than that, no new structure or apparatus needed to be created. Simple cooperation among preexisting military organizations was sufficient. Best of all, it is non-provocative – there is no rival state getting perturbed at the sight of its neighbors performing joint military operations. Pirates may have been surprised to see it when the MSP began, but aren’t really in a position to complain.

The South China Sea, however, presents a great many obstacles to cooperation in contrast to the items described above that facilitate the MSP. For example, while it is mostly a maritime affair, it isn’t entirely – there are actual land masses in play, many of which are large enough to be inhabited. Even rocks and shoals matter, as the long-suffering Philippine LST executing a claim to Second Thomas Shoal in the Spratly Islands can attest.7 So while the typical citizen of an ASEAN state will consider this to be offshore just as the MSP is, the fact is there is still ground to be defended, and China cannot be successfully deterred solely with naval operations. This is a dicey matter since many islands have multiple ASEAN claimants – so who has the responsibility to defend them? Drawing up plans to defend these points from outside aggression will provide frequent flashpoints for internal conflict. It can only be done jointly, or not at all.

Back at sea, naval operations need to be of a higher level than picking up unsophisticated pirates. China must be made to think that, if it comes to war, the costs will outweigh the anticipated gains. Such a credible deterrent requires wholly different equipment and doctrine than that used in the Strait of Malacca. This is expensive and time-consuming. Capabilities vary by country, and in no case do assets come in great numbers. Thus, in contrast with the MSP, outside military assistance is a vital component of Southeast Asian efforts to resist Chinese aggression. Any credible strategy must rely on forces from the United States, at minimum, and probably also Japan, Australia, and perhaps others from outside the immediate region, like India.

Level of Risk

The factors described all figure in to calculations of risk. The bottom line is that counterpiracy is considered to be low-risk; confrontation with China is a dicier proposition. Largely this is because pirates are simply out to make a living, however illicitly; China, on the other hand, appears to be spoiling for a fight.

The People’s Republic of China acts provocatively because it wishes to be provoked. Even if it chooses not to use an incident as a casus belli, it can still use perceived affronts as sanctimonious diplomatic cudgels against their neighbors and rivals. Over time, other countries may subtly shift their behavior to avoid such Chinese outbursts, even if war never actually comes. This means that even quite legitimate expressions of national sovereignty, like the Philippines patrolling its own internationally-recognized waters, might be done infrequently or not at all in order to avoid antagonizing the PRC. A 2015 statement by the U.S. Seventh Fleet commander about the potential about ASEAN counterpiracy patrols in the South China Sea – where, recently, piracy has also been picking up – earned the observation by The Diplomat that “these ASEAN states deal with the South China Sea issue quite differently, and the idea itself may seem too controversial for some for fear of angering Beijing.”8 There is no such restraint in patrolling the Strait of Malacca.

Besides threatening war with the largest military in the region, the PRC can also make economic threats against countries that annoy it. Its market is huge; no country with hopes of growing its economy can afford to ignore it. Thus, a Chinese threat to shut out a certain country or trade bloc carries a certain weight, and gives the PRC substantial leverage in its international dealings. A rival state would have to be pushed thoroughly to the edge by Chinese behavior before it would allow a bellicose response to threaten its access to the Chinese market. This sets a high bar for even one country to oppose Chinese maritime activity in the South China Sea, let alone several of them. Proactive measures against Malacca piracy, though, carries no such risk – as noted earlier, the pirates have no constituency whom rivals must flatter. Individual situations may be difficult (such as those involving hostages) but the impetus to suppress piracy in the first place is unobjectionable as it carries very low risk of blowback.

In fact, counterpiracy has the active encouragement of China and every other maritime nation. The Strait of Malacca is a globally-important chokepoint of trade – disruption there raises the cost of virtually everything, as maritime insurance rates rise and ships are rerouted on longer voyages. China well recognizes its “Malacca Dilemma”9 and pays close diplomatic attention to the area. In fall of 2015, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visited Malaysia and specifically the port of Malacca, giving speeches and offering infrastructure loans along the way. Unlike in the South China Sea, Chinese and Southeast Asian goals are decidedly aligned in the counterpiracy mission and overall security of the Strait.10

Lastly, there is a level of military risk involved, especially as we recall that China is actively looking for grievances. As noted earlier, habitable and buildable islands (and reefs that could become islands) are at issue in the South China Sea – this is not the case in counterpiracy operations. With actual ground on which boots can be disembarked, the stakes are higher than simple maritime cat-and-mouse at sea and in the air. Claiming and holding land by force brings a sort of primacy to a claim that just isn’t achievable by coast guard patrols of open water. Thus ground troops’ use by Southeast Asian states is even more of an incitement to China than maritime operations, and, although it is the only way they can truly enforce their claims, there will be great reluctance to employ such forces. But that leaves the land open for Chinese claims. And the ratchet again clicks ahead one notch.

Additionally, the military-to-military cooperation so prevalent in the MSP would be called out as warmongering if practiced in the South China Sea. Mil-to-mil liaison and cooperation is the order of the day in Malacca; however, if practiced similarly in the South China Sea, a diplomatic row will surely ensue in which China accuses its southern neighbors of ganging up against it (there is a grain of truth to this, of course, even if it’s a defensive arrangement at heart). So, left to their own devices, Southeast Asian states will minimize even simple coordination among their units in the South China Sea in order to avoid rocking the boat and implicitly threatening their economic interests.

Caveats

Discussion of the Malacca Strait Patrol is not meant to sell it is a model example of effective cooperation – simply an example of existing and enduring cooperation. The very fact the MSP was organized and is still extant when so few such international efforts exist in the ASEAN region is, by itself, remarkable. However, questioning its mission effectiveness is perfectly valid. While it did have great success reducing piracy in its earliest years, illicit activity is again on the rise. Southeast Asia was the world’s number-one region for piracy as of 2015, accounting for 55 percent of all cases tracked by the International Maritime Bureau (IMB), with much of it occurring in the Strait of Malacca.11 A check of the IMB’s website12 at any given time will likely show a recent case in the Malacca area (as of this writing, case 071-17, an armed robbery, fits this description).

Contributing to piracy’s resurgence is poor resourcing and rules for cross-border pursuit. Surface ships are not permitted to enter other countries’ territorial waters. Patrol aircraft may make limited incursions of up to three nautical miles; however, they have been “criticized for the low number of flights actually taking place, and the limited resources available to respond to incidents spotted during aerial patrols.”13

It is reasonable to conclude that the great drop in piracy in the first few years of the Malacca Strait Patrol was due to the shock effect among pirates who had to contend with organized resistance for the first time. MSP was able to tackle the “low-hanging fruit” through simple deterrence, and made a big difference. Those who remained in the business were more resilient and innovative in achieving their illegal ends, allowing them to exploit holes in MSP coverage and eventually expand their activities. That, combined with MSP’s inevitable bureaucratic sclerosis and loss of urgency after more than a decade on the same mission contributed to a long-term loss of effectiveness for the counterpiracy effort.

Nevertheless, MSP’s mere existence and the very real success it has had in the past compel its use as an example for other security initiatives – no better ones exist. This has been noted by such figures as the chief of Singapore’s Navy, who in 2015 suggested adapting the MSP model to patrol the recent pirate hotspot in the south end of the South China Sea.14 This specific initiative may be a non-starter for diplomatic reasons described above, but not because the organizational model wouldn’t work.

Courses of Action

MSP states act in the Strait of Malacca because they have undisputed legal authority, only need to expend a moderate amount of funds and manpower, and assess there is low risk of unintended effects. In contrast, China seems to hold all the cards in the South China Sea. Is there anything that neighboring states, or ASEAN as whole, can do to mitigate this?

There may be a way to thread this needle. First, a coalition, optimally but not necessarily ASEAN-based, must be formed to act in the South China Sea. Second, the emerging pirate threat in the South China Sea must clearly and repeatedly be emphasized as the object of efforts in the area. Third, Southeast Asian coalition members must take a page from the Chinese playbook and simply be present there, conducting their counterpiracy mission, to be sure, but also pointedly making their existence a well-known fact. Chinese island-building and occupation must be dealt with diplomatically, as forcibly removing them is a bridge too far, but Southeast Asian presence in the waters concerned will increase Southeast Asian leverage in such discussions.

It is natural to question whether ASEAN has a role in this initiative that affects all of Southeast Asia. Ideally, perhaps it would, and there has certainly been talk of finding ways to accomplish this.15 However, the fact that ASEAN has had no role in the Malacca patrol and has made little substantive contribution to other security matters indicates that this may be an unrealistic expectation. Because of possible diplomatic repercussions from China, it is nearly impossible to even get a joint ASEAN statement concerning the South China Sea, as witnessed in June 2016 with the released-then-retracted statement about Chinese claims.16 Thus, a solution with a better chance of coming to fruition would involve just the directly-involved states, likely Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam (perhaps with Singapore, too). It is unlikely ASEAN would give its blessing, but nor would it get in the way.

When this coalition does kick off its activities, it needs to show in word and action that counterpiracy really is its mission. This is as much a matter of strategic communication as it is maritime tactics, techniques, and procedures. Broadcasting far and wide the news of every apprehended pirate will serve to deter further piracy and also make the point to China that this is, indeed, how the patrols are spending their time. Over time, joint Southeast Asian/ASEAN patrols will become routine and part of the accepted pattern of life in the area.

China will not passively accept this, though. If it does nothing, that would equate to tacit acknowledgment that the affected areas of the South China Sea are either international waters or subject to the claims of nations other than itself, so action is more likely. The Chinese Coast Guard could attempt to keep Southeast Asian patrols out of the area by maneuvers, both diplomatic and naval. But this would beg the question, why is China enabling pirates? It is then possible that China would establish its own counterpiracy operation in order to be seen as doing a service for the region. Piracy, at least, would be mitigated. It would still leave open the thorny issue of the illegitimacy of Chinese actions in ASEAN countries’ claimed seas. Southeast Asian coalition patrols would have to continue, sharing the waters with Chinese ones, in order to show, at the very least, the international nature of the South China Sea.

And, in a roundabout way, we have arrived at the limit of what ASEAN or its member states can expect to accomplish in the South China Sea. They will never resolve their internal claims and counterclaims – but they will never forcibly disabuse China of its claims, either. However, it is just possible they may be able to create conditions in which all sides can agree to disagree. Just as in the Strait of Malacca, the solution is not perfect – as rising rates of piracy show, there are still gaps and the problem is not in any way “solved” – but it is achievable, and the hypothetical outcome is better than it would be otherwise. Let the perfect not be the enemy of the good, and the “good” in this case is a state of tolerable ambiguity.

Conclusion

The mere existence of the Malacca Straits Patrol is remarkable for a region notably protective of sovereignty and averse to interstate cooperation in the wake of colonial rule, and this will be hard to replicate in the South China Sea or elsewhere. The MSP has succeeded because it has a narrowly-defined mission fitted within that paradigm of state sovereignty. It may not have stamped out all piracy, but it’s eliminated quite a bit. Any organization designed to supporting Southeast Asian claims in the South China Sea will need to have a similarly focused mission and expectations to match. No combination of ASEAN member states will be able to in any way “solve” the problem of Chinese maritime claims on their own. But they can act to create the facts necessary to facilitate other efforts, diplomatic and otherwise. The fact that it is the Malaysian or Philippine governments, and not the Chinese government, arresting pirates or helping stranded fishermen could go a long way. But expectations must be limited; any such organization can and should do no more than this.

MSP succeeded by virtue of focusing on goals achievable within the political and resource constraints it faced. In a sense, adapting the MSP organizational model to another mission is easy. MSP’s far bigger lesson is the value of achievable objectives. Setting those objectives requires not money, nor ships, nor men, but rather the most precious resource of all: plentiful reservoirs of discipline.

Matt McLaughlin is a Navy Reserve lieutenant commander, strategic communications consultant, and Naval War College student whose opinions do not represent the Department of Defense, Department of the Navy, or his employer. This post is based on a Naval War College paper submitted in summer of 2016 and is republished with his permission.

Endnotes

1. Catherine Zara Raymond, “Piracy and Armed Robbery in the Malacca Strait: A Problem Solved?”, Naval War College Review, Summer 2009, Vol. 62, No. 3. https://www.usnwc.edu/getattachment/7835607e-388c-4e70-baf1-b00e9fb443f1/Piracy-and-Armed-Robbery-in-the-Malacca-Strait–A-.aspx.

2. Donald E. Weatherbee, Southeast Asia: The Struggle for Autonomy (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015).

3. “Malacca Strait Patrols,” Oceans Beyond Piracy. http://oceansbeyondpiracy.org/matrix/malacca-strait-patrols.

4. Benjamin Kang Lim, “China, Philippines to start South China Sea talks: ambassador”, Reuters, 14 May 2017, accessed 8 Jun 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-silkroad-southchinasea-idUSKBN18A07P.

5. Laura Southgate, “Piracy in the Malacca Strait: Can ASEAN Respond?”, The Diplomat, 8 July 2015, accessed 17 May 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2015/07/piracy-in-the-malacca-strait-can-asean-respond/.

6. “Malacca Straits Patrol: Member States Commemorate 10 Years of Cooperation,” Singapore Ministry of Defense, 21 April 2016, accessed 17 May 2016, http://www.mindef.gov.sg/imindef/press_room/official_releases/nr/2016/apr/21apr16_nr.html#.V3lCerh97IV.

7. Manuel Mogato, “Exclusive: Philippines reinforces rusting ship on Spratly reef outpost – sources,” Reuters wire service, 13 July 2015, accessed 3 July 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-southchinasea-philippines-shoal-exclu-idUSKCN0PN2HN20150714.

8. Prashanth Parameswaran, “ASEAN Patrols in the South China Sea?”, The Diplomat, 19 March 2015, accessed 17 May 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2015/03/asean-patrols-in-the-south-china-sea/.

9. Malcolm Davis, “China’s ‘Malacca Dilemma’ and the Future of the PLA,” China Policy Institute Blog, The University of Nottingham, 21 November 2014, accessed 25 June 2016, https://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/chinapolicyinstitute/2014/11/21/chinas-malacca-dilemma-and-the-future-of-the-pla/.

10. Shannon Tiezzi, “China Promotes Trade, Maritime Silk Road in Malaysia”, The Diplomat, 24 November 2015, accessed 18 June 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2015/11/china-promotes-trade-maritime-silk-road-in-malaysia/.

11. Prashanth Parameswaran, “Over Half of World Piracy Attacks Now in ASEAN,” The Diplomat, 25 April 2016, accessed 17 May 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2015/04/over-half-of-world-piracy-attacks-now-in-asean/.

12. Live Piracy & Armed Robbery Report 2017, International Maritime Bureau, accessed 8 June 2016, https://www.icc-ccs.org/piracy-reporting-centre/live-piracy-report.

13. Laura Southgate, “Piracy in the Malacca Strait: Can ASEAN Respond?”, The Diplomat, 8 July 2015, accessed 17 May 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2015/07/piracy-in-the-malacca-strait-can-asean-respond/.

14. Prashanth Parameswaran, “ASEAN Joint Patrols in the South China Sea?”, The Diplomat, 12 May 2015, accessed 17 May 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2015/05/asean-joint-patrols-in-the-south-china-sea/.

15. Ibid.

16. Robert Held, “South China Sea Clashes Fracturing ASEAN,” The National Interest, 24 June 2016, accessed 25 June 2016, http://nationalinterest.org/feature/south-china-sea-clashes-are-fracturing-asean-16699.

Featured Image: Naval ships on the Strait of Malacca. (Xinhua)