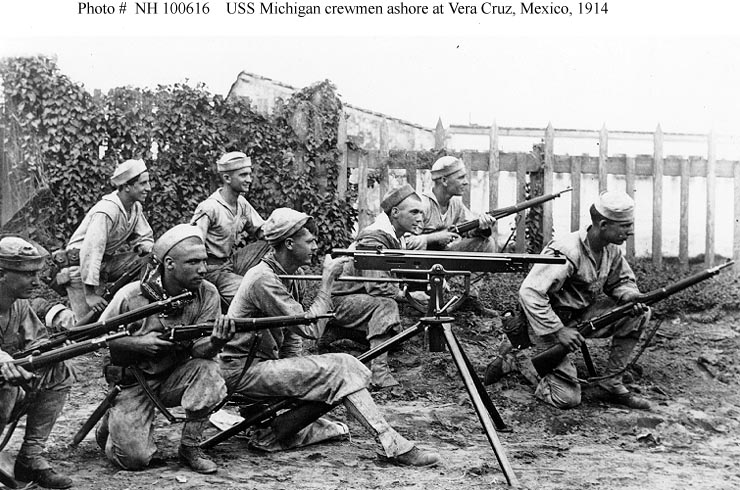

This April marks the 100th anniversary of one of the strangest episodes in the history of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, the mostly forgotten 1914 occupation of Veracruz.

A relatively minor event during the lengthy and violent Mexican Revolution, it is also overshadowed by another American armed intervention in Mexico, the 1916 “Punitive Expedition” led by General John Pershing in pursuit of Pancho Villa. The Veracruz occupation is remembered, if at all, for the embarrassingly large quantity of medals awarded to its participants, and as one of the numerous “small wars” conducted by the Marine Corps in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The roots for the 1914 occupation of Veracruz started a few years earlier, in the chaos caused by the Mexican Revolution. Porfirio Díaz had ruled Mexico as a dictator since the 1870s (re-elected as President through periodic sham elections), but was finally forced from office in 1911 in the face of an opposition coalition that represented the whole spectrum from liberals to warlords and bandits. His successor, the aristocratic but principled liberal Francisco Madero, was soon overthrown and murdered during a 1913 coup led by General Victoriano Huerta, who proceeded to declare himself President.

The U.S. first began creeping towards possible military intervention in Mexico in 1911, with President Taft instructing the Army to create a “Maneuver Division” for use in potential contingencies south of the border. Madero’s death during the Ten Tragic Days (La Decena Trágica) of February 1913, weeks before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration following his defeat of both Taft and Theodore Roosevelt in the 1912 election, resulted in the deployment of U.S. Navy ships to ports on both the east and west coasts of Mexico to observe the situation and protect American citizens and interests.

A month later, in March 2013, Venustiano Carranza established the “Constitutionalist” opposition to Huerta’s government by bringing together another coalition of liberals, regional leaders, and warlords/bandits. By the next spring, Constitutionalist forces had made their way to the vicinity of Tampico, where there was a substantial American presence (mostly due to Tampico’s central role in the Mexican oil industry). Rear Admiral Henry T. Mayo commanded the U.S. Navy forces offshore Tampico.

The direct cause of the U.S. seizure of Veracruz was enabled by the convergence of the U.S. Navy and Constitutionalist army on Tampico. On 9 April 1914, personnel from USS Dolphin were mistakenly and briefly detained by Mexican soldiers (Federales loyal to Huerta) while buying fuel from a warehouse along the river near the front line between the two opposing Mexican armies. Although the Mexican General in command of Huerta’s forces quickly released the American sailors and apologized, Mayo would only be appeased by the Mexicans giving a 21-gun salute to the U.S. flag after it was raised ashore in Tampico; a stipulation that would be unacceptable to any Mexican patriot.

In the following days, tensions were also raised by additional minor insults to U.S. honor, including the arrest of a “mail orderly” from USS Minnesota ashore in Veracruz, and the detention of a courier working for the embassy in Mexico City. In response, on 14 April, President Wilson, whose personal and political distaste for Huerta and his manner of assuming power in Mexico was well known, ordered that the entire Atlantic Fleet immediately proceed from Norfolk to Mexico’s Gulf coast.

By 20 April the stakes had been raised even higher, as the President secretly informed a small group of Congressional leaders that he had been informed by the U.S. consul in Veracruz that a shipment of arms for Huerta’s army was on its way to Veracruz onboard a German cargo ship, Ypiranga. Although Wilson wished to ask for congressional authorization for the use of force against Mexico, he did not wish to publicly disclose his knowledge of the Ypiranga shipment.

Later that night, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels (most historically notorious for outlawing drinking onboard Navy ships) sent a warning order to Rear Admiral Frank F. Fletcher, commander of the ships off Veracruz, to “be prepared on short notice to seize customs house at Vera Cruz. If offered resistance, use all force necessary to seize and hold city and vicinity” The following morning, Fletcher received the order from Daniels to “Seize customs house. Do not permit war supplies to be delivered to Huerta government or any other party.”

This is the first of a three part series on the 1914 invasion and occupation on Veracruz.

Lieutenant Commander Mark Munson is a Naval Intelligence officer currently serving on the OPNAV staff. He has previously served at Naval Special Warfare Group FOUR, the Office of Naval Intelligence, and onboard USS Essex (LHD 2). The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official viewpoints or policies of the Department of Defense or the US Government.

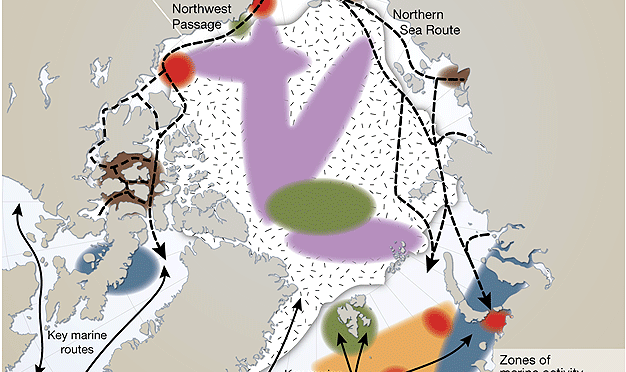

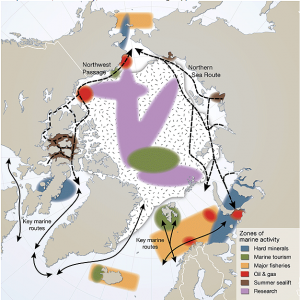

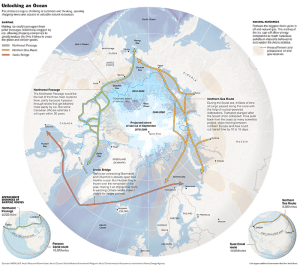

The Arctic region is estimated to have over $1 trillion worth of precious minerals and the equivalent to

The Arctic region is estimated to have over $1 trillion worth of precious minerals and the equivalent to  Most

Most