This is the third of a three part series on the American occupation of Veracuz in 1914. The first and second installments can be found here and here.

24 April marked the end of the combat phase of the U.S. invasion of Veracruz, with the “ABC Powers” of Argentina, Brazil, and Chile offering to mediate between the U.S. and Mexico. President Wilson agreed to participate in these talks and ordered the troops ashore to refrain from offensive operations.

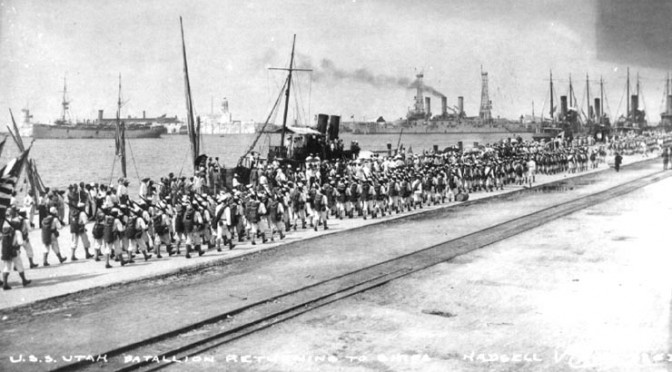

The negotiations proceeded to drag on even though one of Wilson’s original objectives behind the operation was was met in July when Mexican President Victoriano Huerta resigned. However, negotiations with Venustiano Carranza, the head of the Constitutionalist opposition to Huerta who then took power, proved to be not particularly fruitful either, with the parties only coming to a satisfactory agreement for the withdrawal of American troops in November.

Of note, the other main reason for the invasion, preventing the delivery of the weapons onboard Ypiranga to Huerta’s army, was never achieved and did not matter regardless, as they were eventually delivered (the Americans let the ship leave Veracruz in early May and deliver its cargo at Puerto Mexico), but Huerta resigned before they could have any impact on helping the Army keep him in power.

Probably the main reason why some history buffs know about Veracruz is the number of medals awarded to the participants, including men like Smedley Butler and John McCloy who each earned one of their two Medals of Honor there. Members of the sea services earned fifty-five Medals of Honor for heroism or service during the four days of fighting. One reason for that high number was that Veracruz was the first action in which Navy or Marine officers were eligible for the award. Butler was embarrassed by his, stating in his biography that

“I received one, but I returned it to the Navy Department with the statement that I had done nothing which entitled me to this supreme decoration. The correspondence was referred to Admiral Fletcher, who insisted that I certainly deserved the decoration. The Navy Department sent the medal back to me with the order that I should not only keep it this time, but wear it also.”

Another frequently told anecdote has an admiral conducting an inspection in the 1920s, who upon seeing the medal on the chest of a man that had earned it in the First World War exclaimed “Holy smoke! Here’s a Medal of Honor that’s not for Veracruz!”

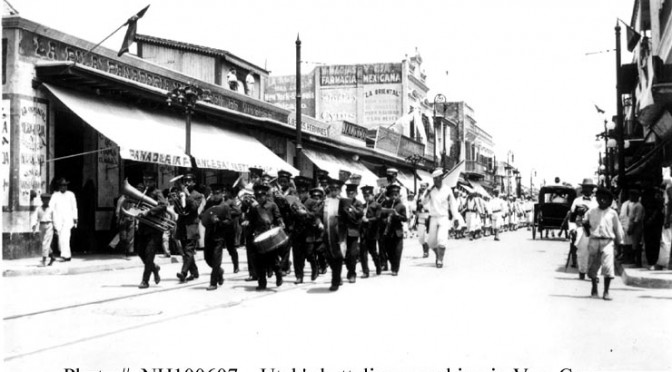

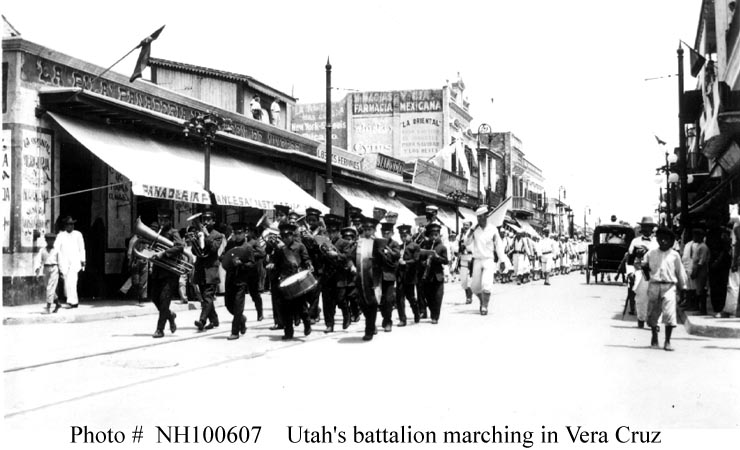

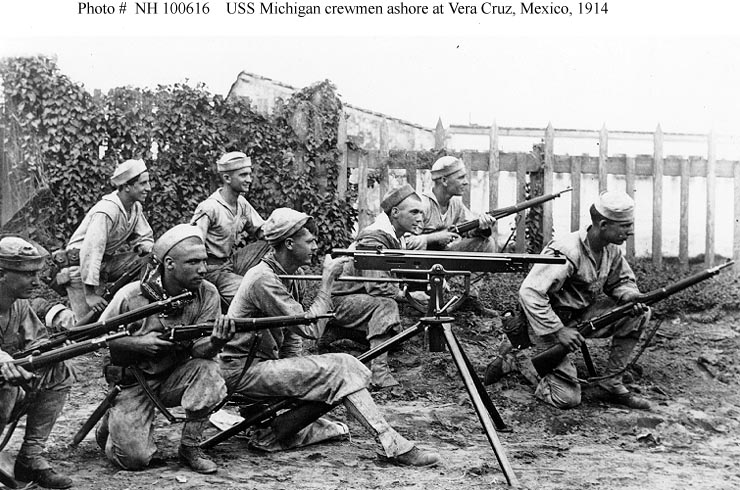

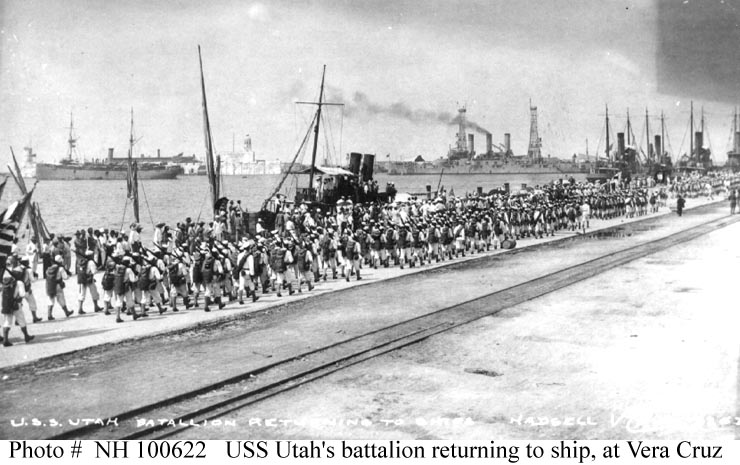

The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps both learned some lessons from Veracruz. It marked Naval aviation’s first involvement in anything resembling combat. It also marked one of the last instances that ship’s company sailors fought ashore as infantry, something that had been relatively common up to that time, with U.S. sailors having recently fought ashore in Latin America, Hawaii, Korea, Samoa, China, and the Philippines. As for the Marine Corps, the 3,000 Marines eventually assembled and sent ashore was “the largest concentration of Marines in the history of the Corps, to date.”

While U.S. memories of Veracruz are almost non-existent today, it had a massive and lasting impact on Mexican attitudes towards its northern neighbor. In Jack Sweetman’s the Landing at Veracruz: 1914, he describes the occupation as “a kind of Caribbean Pearl Harbor.” Even the Constitutionalists fighting against Huerta opposed U.S. military intervention in Mexican affairs, with Pancho Villa the only leading figure in Mexican politics who did not oppose the U.S. landing, ironic in light of him being the main target of another U.S. invasion a few years later. Just as the niños heroiques of 1847 entered the pantheon of national heroes, martyred defenders of the Naval Academy like Cadet Virgilio Uribe and Lieutenant Luis Felipe José Azueta are remembered to this day. A new adjective was added to the title of the Naval Academy, now known as the Heroica Escuela Naval Militar in honor of the cadets’ resistance to the norteamericano invasion. This year the Mexican Navy is participating in a months-long series of events to mark the centenary of an event that the service actually played little part in.

Whether or not the Veracruz operation was a success is difficult to determine. Huerta was forced from office, but one would be hard pressed to prove that the American attack against Veracruz caused his removal. It did not end the Civil War, with Mexico undergoing several more years (or decades, depending on when one believes that the Civil War actually ended) of chaos and violence. A prominent event in Mexican history, it remains mostly a source of obscure service lore to Americans.

Lieutenant Commander Mark Munson is a Naval Intelligence officer currently serving on the OPNAV staff. He has previously served at Naval Special Warfare Group FOUR, the Office of Naval Intelligence, and onboard USS Essex (LHD 2). The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official viewpoints or policies of the Department of Defense or the US Government.