On the night of 23 October 2013, a group of embarked Nigerian policemen on board the tanker HISTRIA CORAL opened fire on a small boat that was approaching a tanker close by on Lagos roads, believing the vessel was under attack by robbers. The small boat, it turned out, was a launch filled with Nigerian Navy personnel, who were about to inspect the ROSE MARY. The episode ended with a stand-off between the Nigerian Navy and the policemen, who eventually locked themselves into the HISTRIA CORAL’s citadel for several days before they were arrested along with the agent who brokered their services.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

This vignette is symptomatic for the state of maritime security in Nigerian waters. Fundamentally, the problem is that, while legislation and capability exist, the patchy enforcement of the applicable laws encourages ship operators, agents, mid-ranking military personnel and private security providers to search for “alternatives” which tend to emphasise practicality over legality. In this they are ably assisted by local “facilitators”.

Responsibilities in Nigerian Maritime Security

The division of responsibilities between the Nigerian Navy and the Nigerian Maritime Police (NMP, a branch of the Nigerian Police Force, NPF) is relatively clear: the NMP has jurisdiction “on the Territorial Inland Waters, (measured from the inward limits of the coastal waterways from the fairway buoy), Ports, and Harbours.” It may extend beyond those limits in hot pursuit or when assisting other agencies.

The Nigerian Navy’s responsibility extends beyond that to include the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), within the bounds of the United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which Nigeria has ratified in 1986. The Navy can also act inshore and to landward based on inter-agency agreements, such as when being a part of the Joint Task Force in the Niger Delta.

However, the lead agency for maritime security, as regards the provisions of the ISPS Code, is actually the Nigerian Maritime Safety Agency (NIMASA). Technically charged with providing port security (in collaboration with Nigerian Ports Authority, NPA) and flag administration, this agency has expanded in recent years to assume a quasi-coast guard role. Some of this is being delivered, controversially, through a private supplier – Global West Vessel Service Ltd, an entity controlled by the former Delta-state militant leader and now billionaire Government Ekpemupolo (Tompolo). NIMASA has also proposed a draft bill on piracy and other unlawful acts at sea in 2012, although that still has to be accepted by Nigeria’s legislators.

Outsourcing Maritime security or Public Private Partnerships?

NIMASA is not alone though when it comes to contracting private companies in order to render what would appear to be asset protection services, but also for maritime surveillance and law enforcement activities. The Nigerian Navy has a tradition of utilising private suppliers to maintain and manage its vessels such as Intels Logistics, who manage the Bonny River convoy or the likes of Ocean Marine Security (OMS) or Protection Plus, who have been supplying escorts vessel services to the Oil & Gas industry for years. Typically, the procedure involves the private companies supplying vessels to the Navy’s specifications. The vessels receive Nigerian Navy pennant numbers and are manned with Nigerian Navy personnel. This has the benefit of providing an effective asset and management outside the Navy’s largely dysfunctional logistical and administrative infrastructure. At the same time, the Navy gains paid-for operational experience. The operational management, although in the hands of the Navy, also places the onus of maintaining situational awareness and response capability on the private partners. As I have described elsewhere, the Nigerian Navy’s organiation in spite of all efforts continues to fail in its ability to generate and disseminate maritime domain awareness information that would enable it to systematically prevent and respond maritime security incidents.

Arguably, the utilisation of Public Private Partnerships (PPP) is best suited to overcome the Nigerian Navy’s organisational shortcomings in the current situation. Nevertheless, like many such decentralised, commercially-tinged activities involving the Nigerian armed forces it bears the risk for abuse, mismanagement and corruption. Above all, it means that the Nigerian Navy relinquishes control and this was exactly what got the Navy in trouble in late 2012 when a merchant vessel, which had hired a Nigerian Navy team, ended up in Togo with the Nigerian soldiers still on board, resulting in some uncomfortable questions being asked of the Navy. As it turned out the Navy’s Western Naval Command had not endorsed the practice of allowing private companies to hire Nigerian Navy teams. To reinforce the point, future co-operation with private partners was based on a standard Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), in which the Nigerian Navy specified that it would provide personnel only for suitably equipped patrol boats. The creation of the Secure Anchorage Area (SAA) outside Lagos in April 2013 in collaboration with OMS was a manifestation of this approach and built on the PPP model that had served the Nigerian Navy well elsewhere.

Use and Abuse of the System

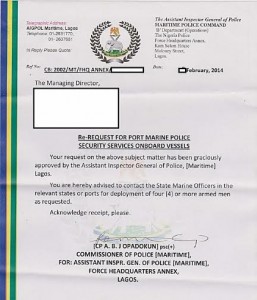

At least 42 security companies registered in Nigeria have signed the MoU with the Navy, although only a fraction have provided the patrol boats as stipulated in the document while the majority of companies thought that they were allowed to use embarked Navy teams. When the Navy pulled the rug from underneath what had apparently become a source of considerable income for local agents, fixers, mid-ranking naval officers and budding Private Maritime Security Companies (PMSCs), it left the shipping industry with only one recourse: to hire Nigerian Police who conveniently offered themselves for this task, although this too was never officially sanctioned by the Inspector General of the Police (IGP) or formalised through anything resembling a MoU. Instead, local police commissioners issued “permits” to agents, PMSCs and ship operators if they wished to embark NMP, ostensibly on behalf of the IGP.

Again, this practice went on for some time for lack of enforcement until the incident involving the HISTRIA CORAL. Under pressure from the political leadership to clean up their act as well as getting a handle on the illegal bunkering and related piracy situation the Navy reacted. This process of reasserting the Navy’s pre-eminence in maritime security (along with NIMASA) was underlined by the politically-induced re-shuffle of the Nigerian armed forces leadership in February 2014 with a clear presidential mandate to enhance the efficiency of the three services.

On 21 March 2014 the Navy arrested an NMP team aboard the tanker CRETE along with two expat advisors from the security firm Port2Port who had accompanied the ship from Lagos to Warri. Although they were held on the whimsical charge of being engaged in illegal bunkering the incident highlighted the increased awareness of the Navy of the use of rogue NMP teams and the determination to intervene when they had knowledge of the practice. The inability of an embarked NMP team to detect an attack in a timely manner and to prevent casualties on the SP BRUSSELS on 29 April 2014 off the Niger Delta also highlighted the low effectiveness of such “rent-a-cop” teams. However, a large number of shipping agents and PMSCs were now firmly wedded to the concept of using NMP and the chronically underfunded NPF also saw a good opportunity in generating some extra income also for their senior personnel who are held in lower regard (and receive a lower pay) than their Nigerian Navy counterparts.

In early June the Nigerian Navy’s Western Naval Command (as well as the two sister commands Central and East) decided to enforce the ban on the use of NMP inside Nigerian territorial waters as directed earlier by the Chief of Naval Staff. Confusingly, the general assertion of authority by the Navy which includes the EEZ (which is part of the Navy’s jurisdiction) was interpreted to imply that the Navy would also enforce this ban on NMP outside territorial waters, which would be in contravention to UNCLOS, leading organisations like the IMO and BIMCO to question the legality of that measure. So far, the Navy has limited itself to inspecting vessels in territorial waters. On 13 June 2014 the Nigerian Navy interrogated a tanker on Lagos roads who first admitted to having embarked security personnel and later denied it. A closer investigation on the 14th revealed the presence of NMP personnel on board and one expat adviser from the same PMSC as on the CRETE. The NMP team was detained and replaced with a Nigerian Navy team so as not to leave the vessel vulnerable to attack.

It is not without irony that within days of the arrests on Lagos roads agents and certain PMSCs signalled their clients in the shipping industry that they had obtained permission to use Nigerian Navy teams – allegedly signed off by a senior naval officer. It is quite plausible that this officer is not yet aware of the “reversal” of the Navy’s enforcement plan that has been enacted in his name and will experience the same surprise as the IGP of Lagos state.

Conclusion

The provision of maritime security services in the Gulf of Guinea is handled more closely by the West African states than has been done by those on the east coast. At the same time effective implementation is slow and frustrating for the shipping industry and the international community.

However, sabotaging the process by playing off law enforcement agencies, or their officers, against each other is unlikely to be helpful in a situation where one of the key problems are fragile states and institutions in the first place. While engaging in collusive corruption (i.e. facilitation payments) the shipping industry is technically not in breach of most anti-corruption legislation, however obtaining an unlawful or “improper” performance from a government agency – even through a third party – might well be subject to more recent anti-bribery legislation such as the UK Bribery Act of 2010 which takes the broader OECD approach to corruption. Furthermore such behaviour perpetuates a system whose unpredictability is a major source of complaint when doing business in Nigeria.

The current modus operandi employed in renting Nigerian government security forces “on the sly” often in contravention of existing but unenforced law and condoned by mid-ranking (and some senior) officers may seem like a good idea now, but in this case it betrays ignorance or casual disregard of the power politics in Nigeria. Choosing to bypass or subvert the Nigerian Navy means antagonising a comparatively influential security service (as opposed to the Nigerian Police) in the Nigerian political system, which is something that is likely to create a backlash in the mid-term as the Nigerian Navy’s organisation continues to strengthen and become more robust as it has, if from a very low level, over the past 7 to 8 years.

Dirk Steffen is the Director Maritime Security for Denmark-based Risk Intelligence. He has been covering the Gulf of Guinea as a consultant and analyst since 2004. He recently deployed to the area with the German Navy in the course of OBANGAME EXPRESS 2014.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]