This is the second of a three-part series. See Jake’s first article here.

China is a Land Power

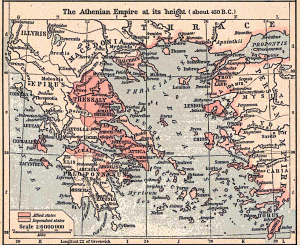

While China continues to invest heavily in a navy, it still remains a continental for several reasons. First, China must maintain a large land force for internal stability and as a deterrent to regional competitors such as India, Vietnam and Russia. It faces demographic, economic and social challenges which threaten the Communist Party’s grip on power. Bernard D. Cole states, “Economic priorities and the need to defend the world’s longest land border with the most nations … still argue against [the PLA(N)’s] ambition for a global navy.”[1] That being said, China continues to develop a navy capable of meeting security interests within the first island chain and most of the South China Sea up to 1,000 nm off the coast.

Second, while China has vastly improved “blue water” capabilities, it has not yet capable of protecting maritime interests beyond the first island chain. Investing heavily in “anti-access/area denial” (A2AD) capabilities is a defensive strategy designed to make the cost of U.S power projection too high. However, A2AD is not a sea control strategy. It does little to prevent the cumulative effect[2] of American (and allied) maritime power to strangle China beyond the first island chain, as outlined by Thomas Hammes.[3] Finally, China’s substantial investment in a navy will likely lead to organizational pressure not to risk it to heavy losses, something which Arquilla and others have also noted. [4]

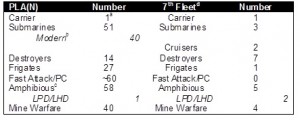

“Quantity has a quality of its own,” and China will enjoy early numerical superiority against forward-deployed American forces. It would take two to three weeks for additional forces to reach the Western Pacific in the event of an unexpected crisis. A comparison of the PLA(N) and forward deployed American naval forces is found below.

Derived from China Naval Modernization (2012) [5]

a- CV 16 “Liaoning”, while commissioned, does not have a carrier air wing.

b- Does not include “Jin” class SSBN or “Ming” class SS

c- Derived from Table 4, pg. 41 of China Naval Modernization (2012)

d- U.S. 7th Fleet derived from public information available at http://www.c7f.navy.mil/forces.htm

Also, while the U.S. has not fought a traditional fleet action since World War II, the Navy has been conducting combat operations around the globe for the past two decades. China, for all the investment and exercises, has not engaged in maritime combat since 1988 in the Spratly Islands with Vietnam. PLA(N) commanders may assume their combat capabilities are better than they actually are, providing unfounded assurance to their own political leadership, increasing the odds of miscalculation.

American Maritime Power and the Strategy to Defeat China

America’s super power status is preserved through the ability to project power across the oceans. While the most obvious component of maritime power is the Navy, it is in jointness with the land, air, space and cyberspace components that makes it formidable. The “pivot” to the Asia-Pacific region must include a reallocation of forces and capabilities. China has continued to aggressively pursue territorial disputes, which have had the effect of driving many Asian countries to seek a greater American presence in the region. A larger land presence is out of the question, but naval and air assets – especially airborne ISR platforms – are much less intrusive and appealing. Space and cyberspace will play a significant (perhaps decisive) role, not only in sensor capabilities but also in defeating A2AD systems and PRC ISR.

The core of American maritime power is built upon destruction of enemy naval forces while preserving its own. Around this core are five pillars: scouting effectiveness, long-range strike, logistics and supply, amphibious assault and coalition warfare.

The Core – Sea Combat and Survivability

The ability to destroy or render inoperable the enemy’s navy – on the surface, in the air or under the sea – is the sine qua non of maritime power. At the same time, the survivability of forces enables the Navy to follow up on success and execute further operations, such as additional combat, blockade, escort or other sea control/sea denial tasks. The introduction of amphibious forces also requires sea combat and may be undertaken in contested waters. A maritime war with China will pit numerically inferior American forces against a formidable yet untested larger PLA(N). U.S. forces must be able to fight, win and survive to carry the war closer to China’s shores.

The Pillars

Scouting effectiveness. Wayne Hughes defines scouting as “the gathering and delivery of information,” a more compact and encompassing term than the currently used “ISR.”[6] It also includes the processing and analysis of vast quantities of all-source information – including space and cyberspace – to provide commanders the best picture possible from which they can make timely decisions. Scouting effectiveness is judged by how quickly information can be turned into actionable intelligence. If commanders can remain inside the decision-making loop of their enemy, they can have a distinct advantage.

Long-range strike. American military development continues to pursue the goal of projecting power from extreme distances or from a position of stealth or sanctuary. Long-range strike should be thought of as a “family of systems,” including land-based bombers, carrier-based strike aircraft (manned and unmanned), rail guns, cruise missiles and supporting airborne electronic attack aircraft.[7] The ability to strike the PRC’s A2AD systems, which are located not only on the coast but also far inland, will be crucial in a maritime fight. In this case, space and cyberspace offensive operations should also be considered in the family of “long range” strike.

Amphibious assault. War is ultimately decided by the “man on the scene with a gun.” The ability to insert land forces onto hostile shores in contested seas may be the ultimate arbiter in a maritime conflict with China, especially in the scenario described above. Even if not used immediately, the credible threat of an amphibious landing could have the effect of tying down Chinese naval, land and air forces hundreds of miles away.

Logistics and supply. In a conflict with China, we should expect that forward supply bases such as those in Japan, South Korea and Guam will become targets, along with supply ships. The flow of food, fuel, forces and ammunition will be the determining factor in our ability to sustain a long-term conflict, so our defense of “sea lanes of communication” (SLOCs) will be tested. Concurrently, the ability to restrict or deny China’s SLOCs should be an early objective of operational planning. A prolonged conflict will test both American and Chinese logistical capacity. The longer America is able to sustain a conflict while controlling SLOCs, the more untenable the Chinese position becomes.

Coalition warfare. The scenario we introduced highlights the importance of coalition and allied warfare. From a perspective of legitimacy, American national security policy has largely adopted the position that the unilateral use of force, while retained, is undesirable. World, and more importantly American, public opinion matters significantly in our ability to conduct and sustain military operations. More importantly, the participation of allies is necessary to offset the quantitative advantages of the PLA(N). The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) and the Republic of Korea Navy (ROKN) are significant forces in their own right, and combined with the U.S. Navy, would match up well against the PLA(N). Third, while some of our coalition partners and allies such as the Philippines, Thailand, Australia, New Zealand or Singapore may not directly participate, they may provide critical logistical hubs or basing. The pillars described above – scouting effectiveness, long-range strike, amphibious assault and logistics and supply – will hinge on the participation and/or support of our allies and friends.

Preparing to Pivot – Restructuring Forward Deployed American Forces

Former Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta suggested that approximately 60 percent of the U.S. naval forces will be postured toward the Pacific region by 2020. How those forces are configured remains a central question.[8]

Current maritime forces are centered on the USS George Washington carrier strike group and a large amphibious task force, CTF 76. The Air Force, Army, Marines and special forces also have a significant presence in the region in Japan, South Korea and Guam.

Future force realignment in the region should include an increase in the number of forward deployed U.S. submarines. The immediate availability of subsurface assets would tip the balance against the numerical advantage of the PLA(N) and allow commanders the option to operate immediately in the first island chain without risking large surface combatants.

In that vein, the development and construction of small fast and stealthy surface missile combatants would provide another avenue to commanders for operations closer in to Chinese waters.[9] Significant investment has already been made in both the littoral combat ship (LCS) and joint high speed vessel (JHSV), which represents a starting point. If equipped with next-generation anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCM’s) such as the Harpoon Block III, advanced capability (ADCAP) torpedoes and SM-2 missiles, these surface combatants could sortie into the East China and Yellow Seas conducting “hit and run” attacks on the PLA(N) surface units as well as protect Japanese and Korean home waters. Further out from the first island chain, they can also be utilized from the Philippines to the Spratly Islands and Singapore to participate in off-shore blockade of the Malacca strait.

Much like the Navy, the Air Force will operate at a numerical disadvantage to the Chinese air and naval air forces. It will fight further from bases, requiring tanker support making them vulnerable and limiting their attack depth. Both the Navy and Air Force will depend on advantages in electronic warfare to blind China’s air forces and air defense systems while fifth generation stealth fighters, such as the F-22, will be critical to achieve air superiority.

Land forces in a maritime conflict are naturally built around maritime assault. However, the presence of a significant force on the Korean peninsula serves as both a deterrent to North Korea attempting to take advantage of a conflict as well as representing a pool of forces to draw from to conduct amphibious operations. Soldiers and Marines stationed on Okinawa, Guam, Korea, Japan and Australia, have to be sufficient in number to conduct a forced entry and capture of any number of island-war scenarios, whether in the tiny Spratly, Paracel or Senkaku Islands to larger ones such as Taiwan.

Land forces also have a role in our own ability to contest the seas and defeat PRC A2AD systems. They can be used to station our own ASCM capabilities among the many islands and littorals in the East and South China Seas. Coupled with land-based rail or traditional gun systems, they could provide an effective deterrence against a PLA(N) sortie and give the PRC leadership pause before initiating conflict.

The opening stages of a maritime conflict with China will be a contest of sea denial. Large American surface combatants will not be operating within the first island chain until Chinese land-based ASCM capabilities are sufficiently neutralized. Control of the undersea, air and space will be bitterly contested. The PRC will attempt to “blind” American ISR and “command and control” capabilities using cyber attacks and anti-satellite (ASAT) missile systems.

U.S. submarines will play a crucial role attriting Chinese naval forces as well as executing strikes against ports and logistic facilities. U.S. land-based and carrier aircraft will begin to contest the skies. With stealthy, fast missile boats, surface forces could sortie out into contested seas. America will not have initial sea control within the first island chain, but should pursue sea denial to limit the PLA(N)’s freedom of action.

At the same time, larger surface action groups made up of guided missile destroyers and cruisers can begin to choke off China’s economic lifelines, especially south of the Spratly Islands and in the Western Pacific. Long-range strike platforms and airborne electronic attack, coupled with space and cyberspace warfare operations, will attempt to roll back China’s formidable integrated air defense (IAD) and A2AD systems. This will create an ever-tightening grip on Chinese economic activity and achieve air superiority in areas critical to the conflict.

About the Author

LT Robert “Jake” Bebber USN is an information warfare officer assigned to the staff of the United States Cyber Command. He holds a Ph.D. in Public Policy from the University of Central Florida. The views expressed here do not represent those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Navy or the U.S. Cyber Command. He welcomes your comments at jbebber@gmail.com.

Sources

[1] Cole, Bernard D. The Great Wall at Sea: China’s Navy in the Twenty-First Century (2nd Ed). Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2010. Pg. 201.

[2] Wylie outlined two types of strategies: sequential and cumulative. A sequential strategy is one in which each success is built upon the other in a march toward victory. He suggests the “island hopping” campaign in the middle Pacific as an example. A cumulative strategy is “made up of a series of lesser actions” which are not “sequentially interdependent.” See pg 22-27 of Military Strategy.

[3] Hammes, T. X. Offshore Control: A Proposed Strategy for an Unlikely Conflict. Washington DC: Institute for National Strategic Studies, National Defense University, 2012.

[4] However, this risk aversion may apply only to newer, modern platforms. The PLA(N) may be more willing to sortie older surface combatants which are still heavily armed anti-ship cruise missile (ASCM) platforms

[5] O’Rourke, Ronald. China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities – Background and Issues for Congress. CRS Report for Congress, Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2012.

[6]Wayne P. Hughes, Jr. “Naval Operations: A Close Look at the Operational Level of War at Sea.” Naval War College Review, 2012: 23-47. Pg. 32.

[7] Gunzinger, Mark A. Sustaining America’s Advantage in Long-Range Strike. Washington DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2010. Pg. ix.

[8] Neisloss, Liz. U.S. defense secretary announces new strategy with Asia. June 2, 2012. http://edition.cnn.com/2012/06/02/us/panetta-asia/index.html (accessed December 1, 2012).

[9] Huges, op cit., Pg. 29.