The following article originally appeared in South Asia Defence and Strategic Review and is republished with permission.

By Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan, AVSM & Bar, VSM, IN (Retd)

Japan is very much the flavor of the current Indian season. Especially when juxtaposed against China, Japan is acknowledged by New Delhi as being one of the most significant maritime players in the Indo-Pacific. Indeed, Japan’s steadily deteriorating and increasingly fractious relationship with China is a prominent marker of the general fragility of the geopolitical situation prevailing almost throughout the Indo-Pacific. Within this fragile environment, New Delhi is seeking to maintain its own geopolitical pre-eminence in the IOR and relevance in the Indo-Pacific as a whole by adroitly managing China’s growing assertiveness. In this process, Japan and the USA (along with Australia, Vietnam, South Korea, and Indonesia) collectively offer India a viable alternative to Sino-centric hegemony within the region. However, before it places too many of its security eggs in a Japanese basket, it is important for India to examine at least the more prominent historical and contemporary contours of the Sino-Japanese relationship. As India expands her footprint across the Indo-Pacific and examines the overtures of Japan and the USA to seek closer geopolitical coordination with both, it is vital to ensure that our country and our navy are not dragged by ignorance, misinformation or disinformation, into the law of unintended consequences.

The influence of China, with its ancient and extraordinarily well-developed civilization, upon the much younger civilization of Japan1 has been enormous. Even the sobriquet for Japan — the Land of the Rising Sun — is derived from a Chinese perspective, since when the Chinese looked east to Japan they looked in the direction of the dawn. As Japan began to consolidate itself as a nation, between the 1st and the 6th Century CE, it increasingly copied the Chinese model of national development, administration, societal structure and culture. And yet, for all that, there is also a history of deep animosity between the two countries, which manifested itself across of whole range of actions and reactions. At one end was China’s disapproval of Japan attempting to equate itself with the Middle Kingdom (as when Japan Prince Shotoku, in 607 CE, sent a letter to the Sui emperor, Yangdi, “from the Son of Heaven in the land where the sun rises to the Son of Heaven in the land where the sun sets.”) At the other, lay armed conflict. Over the course of the past two millennia, Japan and China have gone to war five times. The common thread in each has been a power struggle on the Korean Peninsula. Even their more contemporary animosity dates back to at least 1894 — during the Meiji Restoration in Japan. It is true that, much like India and Pakistan, relations between China and Japan have witnessed periods of great optimism. For instance, Sino–Japanese relations in the 1970s and early 1980s were undeniably positive and ‘historical animosity’ was not a factor strong enough to foster tensions between the two nations at the time. However, it is also true, once again like India and Pakistan, that these periods of hope have been punctuated by a mutuality of visceral hatred. In the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, China, which was mired in political conflict and civil war, suffered eight months of comprehensive defeats leading, amongst other indignities, to the occupation of Taiwan by Japan. The historical echoes of this horrific conflict and its humiliating aftermath for China resonate to this day.

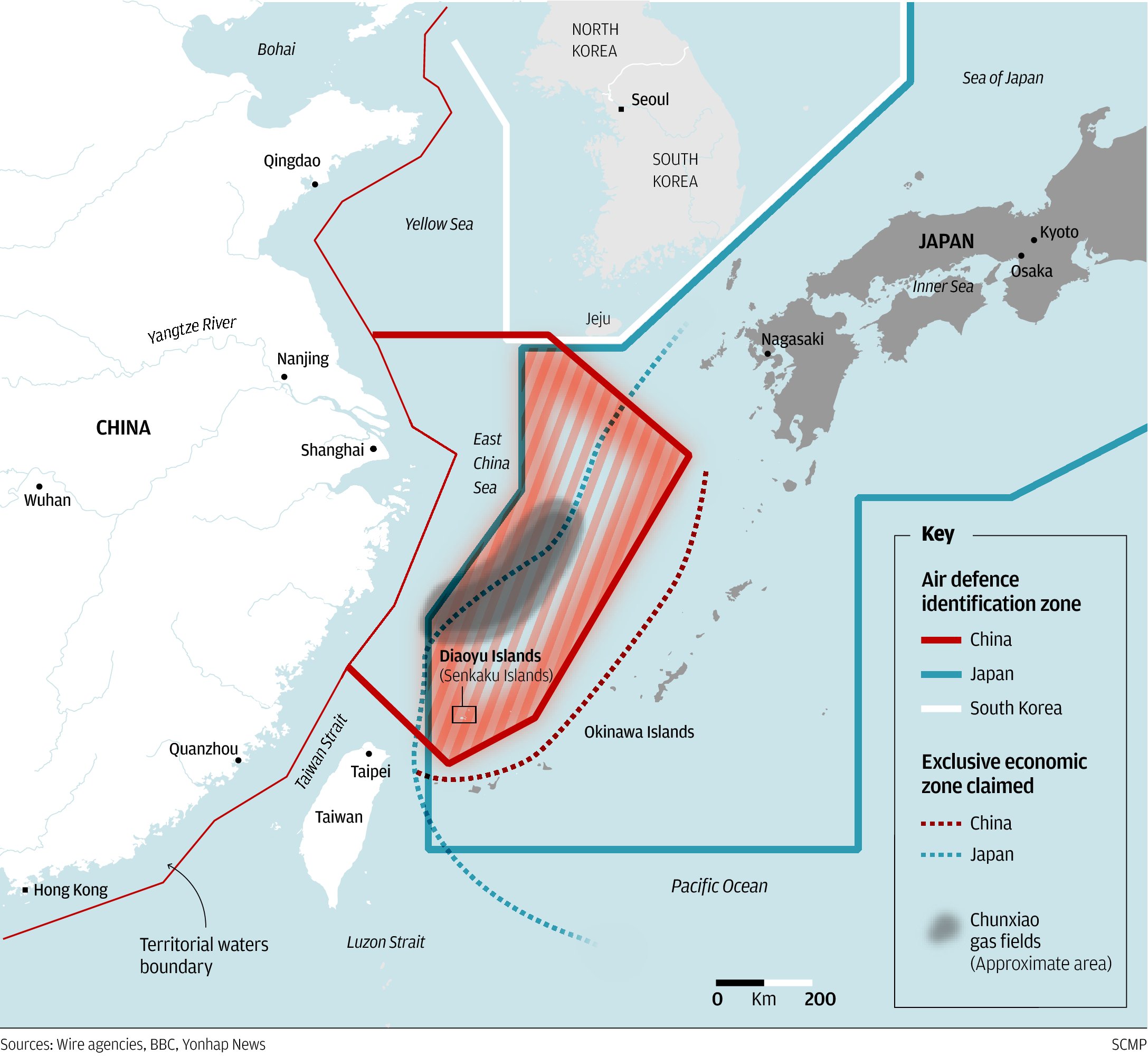

The most prominent Sino-Japanese contributor to contemporary geopolitical fragility is the Senkaku/ Diaoyu Islands dispute. This is an extremely high-risk dispute that could very easily lead to armed conflict, especially in the wake of Japan’s nationalization of three of the islands in September 2013. Reacting strongly to this unilateral action by Japan, China established an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) on 23 November, 2013, encompassing (inter alia) these very islands. This, in turn, was immediately challenged by the USA, Japan, and South Korea. Within days of the Chinese declaration, military aircraft from all three countries flew through China’s ADIZ without complying with the promulgated ADIZ regulations. Perhaps because of the robustness of this response, China has not been enforcing this ADIZ with any great vigour, but has not withdrawn it either. It is appreciated that this is a long-term play, because China would acquire strategic advantage by asserting a maximalist position, then seeming to back down, while preserving some incremental gain — akin to a ‘ratchet’ effect. This is an example of ‘salami slicing’ — of which much has been made in a variety of Indian and Western media.

China’s increased military activities in this maritime area have certainly caused a fivefold rise in the frequency with which Japanese fighter jets have been forced to scramble in preparedness against Chinese aircraft intrusions into Japanese airspace over the East China Sea (ECS). Japanese aircraft have moved up from 150 scrambles in 2011 to a staggering 1,168 scrambles in FY 2016-17. (The Japanese FY, like that of India, runs from 01 April to 31 March.) Given that fighter pilots are young, aggressive, and trained to use lethal force almost intuitively, this dramatic increase in frequency of scrambles causes a corresponding increase in the chance of a miscalculation on the part of one or both parties that could result in a sudden escalation into active hostilities.

Even more worrying is the prospect that once China completes her building of airfields on a sufficient number of reefs in the Spratly Island Group, she would promulgate an ADIZ in the South China Sea. Should she do so, the inevitable challenges to such an ADIZ would probably bring inter-state geopolitical tensions to breaking point.

All in all, the increased militarization and current involvement of the armed forces of both countries in the Senkaku/ Diaoyu islands have grave implications for geopolitical stability. To cite a well-used colloquialism, “once you open a can of worms, the only way you can put them back is to use a bigger can.” In the case of the Senkaku/ Diaoyu Islands, both Japan and the PRC have certainly opened ‘a can of worms’ and now both are looking for a bigger can. Thus, both countries are jockeying for geopolitical options with both the USA as well as with other geopolitical powers that can be brought around to roughly align with their respective point of view. Japan’s alliance with the USA and its active wooing of India and Australia with constructs such as Asia’s Democratic Security Diamond is one such ‘larger can.’

Yet, Japan’s geopolitical insecurities in its segment of the Indo-Pacific are not solely about the Senkaku/ Diaoyu islands. Japan’s apprehension in 2004-05 that China’s exploitation of the Chunxiao gas field (located almost on the EEZ boundary line — as Japan perceives it) was pulling natural gas away from the subterranean extension of the field into the Japanese side of the EEZ boundary brought the two countries to the brink of a military clash. While the situation has been contained for the time being, it remains a potential flashpoint. Across the Sea of Japan /East Sea lie other historical and contemporary challenges in the form of the two Koreas, a Russia that appears to be in a protracted state of geopolitical flux, and of course, the omnipresent elephant in the room, namely, the People’s Republic of China.

Closer home, Japan’s Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF) is present and surprisingly active in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) as well. Its interest in maintaining freedom of navigation within the International Shipping Lanes to and from West Asia in general, and the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Aden in particular, are well known features of Tokyo’s ‘energy security’ and ‘security-of-energy’ policies. Off the Horn of Africa at the southern tip of the Gulf of Aden, the ‘war-lord-ism’ that substitutes for governance in Somalia is a source of strategic concern at a number of levels. Although rampant piracy and armed-robbery have been checked for the time being, only the most naive optimism can indicate anything but continued strategic instability in and off Somalia — at least for the foreseeable future. The JMSDF’s deployments on anti-piracy missions, involving two destroyers and two long-range maritime-patrol (LRMP) aircraft, have been ongoing since 2009 and will continue through 2017. However, such deployments are at the cost of the JMSDF ORBAT (Order of Battle) within the ECS and the Sea of Japan — areas where, as has already been described, Japan faces far more serious and immediate threats than in West Asia. If India was to explicitly offer the protection of its Navy specifically to Japanese merchantmen in and around the Gulf of Aden, this might free the JMSDF warships and LRMP aircraft from this maritime space and permit them to be redeployed in the ECS to contain and counter China’s naval as well as ‘grey zone’ operations (the latter involving predominantly paramilitary maritime forces). Of course, within the north Arabian Sea, the JMSDF has commitments to the USA-led Coalition Task Force (CTF) 150 (in and off the Persian Gulf) as also to CTF 151 (in and off the Gulf of Aden), which would also have to be factored. These notwithstanding, a specific Indian commitment of Indian naval anti-piracy protection to Japanese trade is likely to go down very well with both Tokyo and Washington, and is something that the Indian Navy with its present warship resources could certainly manage.

As is the case with India, Japan, too, is engaged in a series of ongoing efforts to reduce its energy-vulnerabilities. For both India and Japan, this has brought centrality to the environs of the Mozambique Channel, a sadly neglected chokepoint of the IOR, but one that now offers a great deal in terms of strategic collaboration and coordination between Tokyo and New Delhi. To the northwest of this sea passage, Tanzania is engaged in an intense rivalry with Mozambique over newly discovered offshore gas fields in both countries. Tanzanian offshore discoveries off its southern coast, between 2012 and 2015, have raised the official figure of exploitable reserves to as much as 55 trillion cubic feet (tcf). As a comparator, India’s recoverable reserves are 52.6 tcf. The story in Mozambique is even more promising. Since 2010, Anadarko Petroleum of the US, and Italy’s Eni, have made gas discoveries in the Rovuma Basin in the Indian Ocean that are estimated by the IMF collectively to approximate 180 tcf, equivalent to the entire gas reserves of Nigeria. When developed, these gas reserves have the potential to transform Tanzania and Mozambique into key global suppliers of liquefied natural gas. Indeed, once gas production hits its peak, Mozambique (in particular) could well become the world’s third-biggest liquefied natural gas exporter after Qatar and Australia. Obviously, India and Japan, not to mention China, are deeply interested in this LNG as it will allow each country to ‘wake up’ — at least partially — from their common ‘Hormuz Nightmare’ vis-à-vis the sourcing of LNG from Qatar. Where India is concerned, LNG from Rovumo will additionally negate any Chinese-Pakistani interdiction-possibilities ex-Gwadar. In fact, just as the Gulf of Guinea on the western coast of Africa is a vastly preferred source of petroleum-based energy for Europe and the USA precisely because there are no chokepoints along the route from source-to-destination, a somewhat-similar situation would prevail for India, Japan, and China were they to source their energy from East Africa and the Mozambique Channel.

It is therefore encouraging to note that by April 2015, an Indian consortium comprising the ONGC, IOL, and BPC had purchased a combined 30 percent stake in Anadarko’s ‘Rovuma’ fields at a cost of US $6.5 billion to be amortised over a four year period. Japan and South Korea, too, — both growing partners of India — have invested with both Anadarko and Eni: the Japanese energy company Mitsui now holds a 25 percent stake in Anadarko’s concession and Korean Gas Corp (Kogas) holds a 10 percent stake in Eni’s concession. Unsurprisingly, China, too, is a major player and the ‘China National Petroleum Company’ (CNPC) has bought into the Italian firm ‘Eni’ to the tune of US $ 4.2 Billion, for a 28 percent stake. Once this LNG begins to be shipped eastwards, the Indian Navy could once again be the guarantor of Japanese Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs) at least from Mozambique to the SCS, if not all the way to Japan.

Another important driver for Japanese strategic maritime interest in the IOR is food security. Often given insufficient attention by Indian analysts, this is, nevertheless a significant factor in Japan’s geopolitics. Even though Japan is amongst the world’s richest countries, her food self-sufficiency ratio is remarkably low compared to other industrialized nations. In particular, Japan’s high cereal import dependency rate and low food self-sufficiency rate make her particularly vulnerable. As of 2015, Japan was producing only about 39 percent of the food it consumed reflecting a major decrease from the 79 percent in 1960, and the lowest food self-sufficiency ratio among all major developed countries. Moreover, Japan depends on a very small number of countries for the majority of its food imports — 25 percent come from the USA alone, while China, ASEAN and the EU account for another 39 percent — and all of it travels by sea. In order to reduce her consequent geopolitical vulnerability and diversify her SLOCs, Japan has invested in agricultural projects (the purchase, from relatively poor nations abroad, of enormous tracts of farmland upon which food is grown and shipped back to Japan). This activity, which has serious ethical issues associated with it, is considered by ethical activists to be ‘land grabbing’, especially as it takes callous advantage of the need for cash-strapped African nations for money, leading the governments of these countries to deny their own (often impoverished) people the agricultural produce of their own land. Nevertheless, ‘farming abroad’ has emerged as a new food supply strategy by several import-dependent governments, including Japan. Where Japan is concerned, several of its large-scale investments are concentrated in Mozambique, causing Japan to concern herself with the geopolitical stability of this portion of the Indian Ocean and the International Sea Lanes (ISLs)/SLOCs leading to Japan. This drives the noticeable fluctuation between Japan’s commitments to contribute to international development policies and the more narrow-minded pursuit of its national interests and intensified efforts to strengthen its position in international politics in relation to China. For New Delhi, however, this represents yet another opportunity to leverage Indian naval capability to commit itself to keeping Japanese ‘Food SLOCs’ open and safe.

Zooming in to India’s immediate maritime neighbourhood, Japan’s willingness to partner with vulnerable countries in planning activities, and also provide for and engage in preventive and curative measures with regard to Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR), holds great promise for an active India-Japan partnership under a joint IONS-WPNS rubric. The benefits that would accrue from such an initiative have very substantial and substantive strategic implications.

With Pakistan remaining a constant spoiler and a global sponsor of terrorism, India’s hugely improved relations with Bangladesh offer additional opportunities for New Delhi to coordinate its own maritime strategic gameplay with that of Japan. Japan, for instance, is poised to provide a viable alternative to the now abandoned Chinese-sponsored Sonadia Port project in Bangladesh, by way of the development of a coal-based 1,200 MW power plant as well as a new deep-water port at Matarbari in Cox’s Bazaar, just 25 km away from Sonadia.

India’s own maritime engagement with Japan is being driven along at a brisk pace by a strong mutuality of interests, and a number of institutional mechanisms at both Track-1 and Track-2 levels are now functional. At the Track-1 level, maritime engagement per se is provided focus through the ‘India-Japan Maritime Affairs Dialogue,’ which was established in January 2013. Spearheaded by India’s MEA (Disarmament and International Security Affairs [DISA] Division) and Japan’s Foreign Policy Bureau, the dialogue covers a wide ambit, including, inter alia, maritime security including non-traditional threats, cooperation in shipping, marine sciences and technology, and marine biodiversity and cooperation. However, the bilateral maritime-security engagement is probably the most relevant to the Indian maritime interest under discussion, namely, the obtaining and sustaining of a favourable geopolitical position. It is vital to bear in mind that, contrary to many Indian pundits who examine geoeconomics in isolation, geoeconomics is a subset of geopolitics, as is geostrategy. To reduce it a simple equation, Geopolitics = Geoeconomics + Geostrategies to attain geoeconomic goals + Geostrategies to attain non-economic goals + Interpersonal Relations between the leaders of the countries involved.

Within the Indian EEZ, India-Japan-USA maritime-scientific cooperation is already in evidence in one of the most exciting and promising areas of energy, namely, gas hydrates. Gas hydrates, popularly called ‘fire-ice,’ are a mixture of natural gas (usually methane) and water, which have been frozen into solid chunks. In 1997, in recognition of the tremendous energy-potential in gas hydrates, New Delhi formulated a ‘National Gas Hydrate Programme’ (NGHP) for the exploration and exploitation of the gas-hydrate resources of the country, which are currently estimated at over 67,000 tcf (1,894 trillion cubic meters [tcm]). Once again, as a comparator, India’s exploitable reserve of conventional LNG is a mere 52.6 tcf. The two exploratory expeditions (NGHP-01 and NGHP-02) that have thus far been mounted have been in conjunction with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (J AMSTEC). They have yielded extremely encouraging results that border on the spectacular, confirming the presence of large, highly saturated, accumulations of gas hydrates in the Krishna-Godavari (KG) and Mahanadi Basins that are amongst the richest in the world. Production of even 10 percent from this natural reserve would be sufficient to meet the country’s vast energy requirement for a century or more — a cause of considerable optimism for energy-starved India and Japan. The 2015 edition of the ‘India-Japan Science Summit’, too, has reiterated the intent of both countries to continue joint surveys for gas-hydrates within India’s EEZ, using the Japanese drilling ship, the Chikyu.

Military interaction with Japan is progressing at the policy level through the Japan-India Defense Policy Dialogue, while operational-level engagement proceeds under the aegis of the Comprehensive Security Dialogue (CSD) and Military-to-Military Talks (initiated in 2001). Naval cooperation is by far the most dynamic and is steered through the mechanism of annual Navy-to-Navy Staff Talks.

Tokyo and New Delhi are also actively expanding their defense trade and the acquisition by India of Japanese ShinMaywa US-2i amphibious aircraft remains very likely. Japan is also looking to undertake the construction of maritime infrastructure in the Andaman and Nicobar (A & N) Islands. An eventual aim could well be to integrate a new network of Indian Navy sensors into the existing Japan-U.S. “Fish Hook” Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) network to monitor the movement of Chinese nuclear-powered submarines.

As Satoru Nagao of the Tokyo Foundation, writing in the ORF’s publication Line in the Waters succinctly puts it, “Tokyo and New Delhi have an important role to play to advance peace and stability and help safeguard vital sea lanes in the wider Indo-Pacific region. Since Asia’s economies are bound by sea, maritime democracies like Japan and India must work together to help build a stable, liberal, rules-based order in Asia.”

Clearly, there is a mutual yen for a closer maritime engagement.

Vice Admiral Pradeep Chauhan retired as Commandant of the Indian Naval Academy at Ezhimala. He is an alumnus of the prestigious National Defence College.

[1] Chinese civilizational framework prevailed throughout the East Asian region, but the Japanese version of it was distinctive enough to be regarded as a civilization sui generis.

Featured Image: Group photograph on board INS Shivalik with Japanese Naval Seadership at Port Sasbo, Japan on 24 Jul 14 (Indian Navy)