This article was originally published by the South Asia Analysis Group. It is republished here with the author’s permission. Read the article in its original form here.

“An Opportunity for India to showcase the Capacity, Capability, and Intent of a strong, vibrant, emerging Maritime Nation in the 21st Century.”

The IFR 2016 will indeed be a grand spectacle as more than one hundred ships from the navies of over fifty countries will participate in this exercise that is carried out every five years. The event, which in the initial years was mostly limited to the participation of ships from the Indian Navy, Indian Coast Guard and the merchant navy, has transformed in to an international event with a major maritime event conducted in 2001 under the initiative of then Chief of Naval Staff Admiral Susheel Kumar. The marching of the naval officers and sailors from ships around the world along the marine drive in Mumbai and the presence of ships from around the world signaled a new era in maritime diplomacy. The intentions of a maritime India to occupy center stage in both regional and global missions by using the Indian Navy as an instrument of national policy were explicit.

As the participants of the IFR witnessed scores of indigenous ships of the Indian Navy, it was evident that the Indian Navy was in the process of transforming from a buyer’s navy to a builder’s navy. The process was a prerequisite to assuming greater regional leadership role and responsibilities. This did not escape the attention of the participant nations and motivated them to engage with India at many levels. It is not to be forgotten that this initiative was taken under the leadership of Admiral Susheel Kumar, who succeeded Admiral Vishnu Bhagwat. Admiral Bhagwat was relieved of his duties as CNS on 30 December 1998 by the NDA Government under certain debatable circumstances. The Navy’s morale, which was dented, had to be built up brick by brick and the IFR of 2001 from that point of view provided a launching pad for the force that was fast becoming a blue water Navy. The theme ‘Bridges of Friendship’ was very well received and created an environment that facilitated the process of integration of a regional navy in to a global matrix.

While both the Indian Navy and the Indian Coast Guard have conducted the Fleet Reviews on the east coast (The very first Indian Coast Guard Fleet Review by the Raksha Mantri was conducted off the east coast when the author was the Regional Commander of the Indian Coast Guard, Region East), this is the first time that an international fleet review of this scale is being conducted in the Bay of Bengal. By design, this also complements the ‘Look East’ policy of the Government of India. It also adds value to other maritime initiatives, such as the biannual Milan (established as an initiative for meeting of the naval minds in Port Blair) and the Indian Ocean Symposium (IONS), now a well-established forum among Navies of not just the Indian Ocean but also the rest of the world.

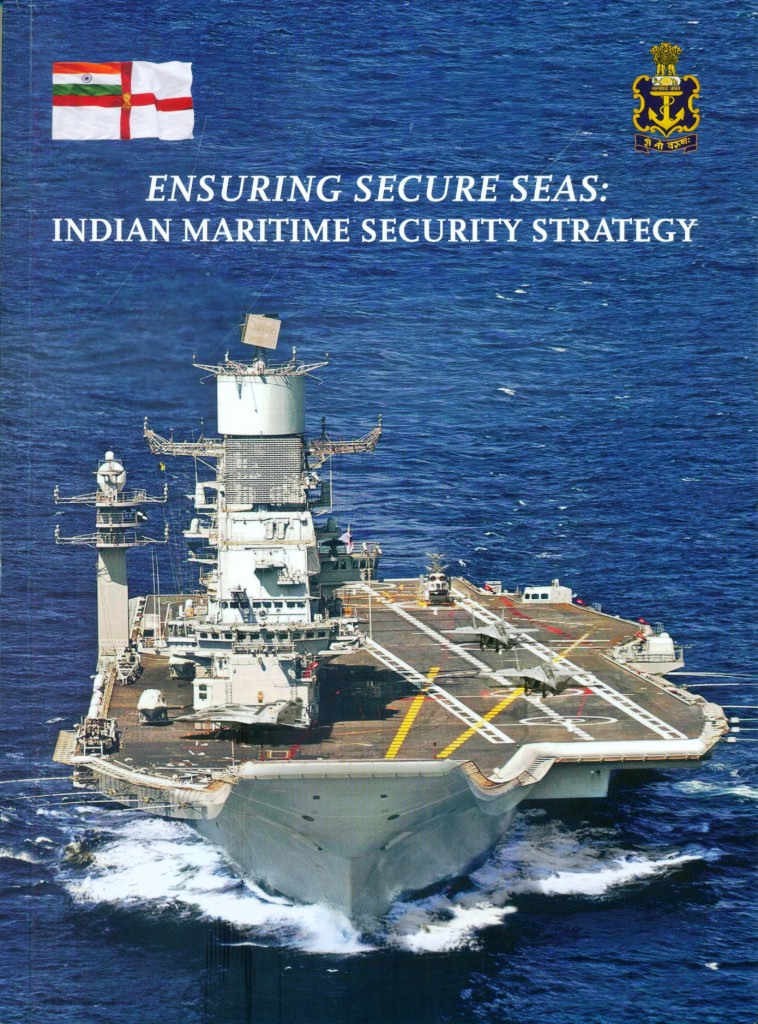

By all expectations, China will be a first-time participant in the Indian Fleet Review. From the point of view of PLA-Navy, participation signals its intention to be a part of global initiatives in the Indian Ocean. The anti-piracy patrols by PLAN units, which are still underway off the coast of Somalia, provided ample opportunity for the Chinese Navy to assert its intention to be part of the international mechanisms to combat piracy. Both the Indian Navy and the Chinese Navy worked shoulder to shoulder in warding off this threat, though India was concerned about the presence of another extra regional player in its traditional back yard. The visit of the Chinese submarines both conventional and nuclear last year again caused ripples in Delhi. There are no doubts that India and China will jostle for power and influence in the Indian Ocean Region. While India does have geography on its side, the surplus funds that can be channeled for initiatives such as the Maritime Silk Road and the One Belt One Road will change the strategic landscape of Indian Ocean Region. The IFR also comes at a time when there are great initiatives being taken by China in Asia, Africa and Europe in terms of connectivity. The fact that the PRC plans to build a naval base in Djibouti and has huge investments in the maritime sector in Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Bangladesh, and Pakistan are of concern to India, which appears to have conceded strategic space to China in its areas of influence. The presence of the INS Vikramaditya and India’s nuclear submarines would send a message to observers about the might of the Indian Navy that can be brought to bear as and when required in areas of interest. The presence of a P-8i surveillance aircraft could also generate interest in the capability of this newly acquired platform, capable of locating and tracking submarines and surface assets of extra-regional powers in the Indian Ocean. The message that the Indian Navy is net-centric warfare capable as a result of plenty of indigenous efforts would be very clear.

The Indian Navy has inherited many of the traditions and practices from the Royal Indian Navy while adding its own local flavor. The President of India, by virtue of being the Supreme Commander of the Armed forces, reviews the fleet invariably before he or she demits office during the tenure of five years as the President. It is a mega-event by any standards, and even the state Government has committed more than 83 crores in beautifying the city of Vizag, which houses the Eastern Naval Command and important maintenance facilities of the Navy. It is also the base for the nuclear submarines of the Indian Navy, including strategic assets. All the arrangements have been reviewed at the level of the Raksha Mantri and the Navy and nation are geared up for this event in the first week of February that will showcase the prowess of the Indian Navy. A successful conclusion of the IFR will reinforce the position of the Indian Navy as a professional arm that can be used as a powerful instrument of national policy both in war and peace.

Historically, the role of the Indian Navy after the spectacular missile attacks on ships and oil tank farms Karachi in 1971, with the then-only Asian carrier Vikrant enforcing a blockade off then East Pakistan indicates how it is important to possess and use a strong navy for furthering national objectives. The fact that the Indian Navy was not used at all during the war in 1965 therefore comes as a surprise. The role of the Indian Navy during the tsunami of 2004, its evacuation of Indian nationals from war torn areas, and its ability to relief and succor to the flood and cyclone affected victims on many occasions highlights strength of the Indian Navy that has proved its mettle.

The Mumbai terror attack in November 2008 changed the way maritime threats were perceived and brought about a paradigm shift in the maritime security architecture (MSA). The Indian Navy was placed at the apex of the MSA and made responsible for both coastal and oceanic security. Without going into the details, suffice it to say that the entire gamut of maritime threats and response mechanisms have undergone a sea change.

It is not out of place to recollect that it was the Indian Navy that first brought out a National Maritime Doctrine in 2004 revised it in 2007, 2009, and 2015. Even in terms of indigenization, the Indian Navy is way ahead of its sister services, having embarked on indigenization in the late 60s. The first indigenous frigate Nilgiri and its follow-ons have provided the nation with options for ship building in both PSUs and private yards. The fact that the Indian Navy was able to even design a carrier and orchestrate its construction in the Cochin Shipyard Limited is a tribute to the leadership, the naval designers, and in-house capability to produce warships of different size. The design of stealth ships such as the Shivalik, large destroyers such as the INS Kochi, construction of corvettes, and the completion of the naval off-shore vessels are all praiseworthy. The most notable feature of the Indian Navy’s indigenization process is the addition of INS Arihant which provides that strategic deterrence capability that eluded India for many decades. The construction of improved versions of Arihant and also the Indigenous Aircraft Carrier (IAC) are logical

conclusions to the aspirations of a blue water navy that has both regional and global roles. However, the dwindling strength of conventional submarines has been a source of great concern to the planners in Delhi. There are some recent efforts to ensure that this serious deficiency is overcome both by accelerating the Scorpene production and also embarking on the indigenous production of project 75A submarines for which more than 60,000 crores has been earmarked.

The shape and size of the Indian Navy is formidable as India moves in to the next century. With geography and a growing economy on its side, India’s Navy will continue to complement the ambitions of a maritime India. A powerful Navy will promote maritime safety and security in the Indian Ocean. As a guarantor of net security at sea, safeguarding the global commons, maritime interests, and the sea lines of communications that represent the life lines and arteries of global trade and commerce will be a top priority for the Indian Navy.

India is conscious of the fact that there are rich dividends in forging strategic alliance with other like-minded nations on a case by case basis while retaining its strategic autonomy. The trilateral treaty with Sri Lanka and Maldives and Exercise Malabar or other such exercises are all measures to ensure that the maritime domain remains manageable and the Indian Navy is in a position to control the happenings in areas of interest. Maritime engagement with Mauritius, Seychelles, Mombasa, Oman, and other maritime nations are all significant in ensuring that there is seamless integration of the maritime domain, and that all the maritime nations in the region are under one umbrella and can work in unison to serve the interests of the century of the seas. The IFR will be a keenly watched event around the world and the navies who are part of this Indian initiative will carry back cherished memories from this mega-event. From the point of view of the Indian Navy, it will again provide an opportunity to take the initiative from “Building Bridges of Friendship” in 2001 to an architecture that is “United through Oceans” in 2016 and beyond.