Alternate History Topic Week

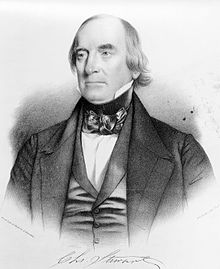

Having just completed his latest assignment as Commodore of the Home Squadron, Charles Stewart had returned to his intermittent business interests that had afforded opportunities to officers without orders. He had seen the flyers, his stately image emblazoned above the appeals for him to run for president of the United States. At the behest of fellow Philadelphian merchants, he agreed to join them in Baltimore where both the Whigs and Democrats held their conventions. Henry Clay was already certain to be the Whig nominee; the fight for the Democratic nomination was far more complex.

Martin van Buren’s lock began to falter based on his position on slavery and opposition to the annexation of Texas. War of 1812 hero Lewis Cass supported annexation. There were other contenders: James Buchanan, John C. Calhoun, and Silas Wright. In the background was the decidedly non-political hero of the War with the French in 1798, the Barbary War, and the War of 1812. Van Buren was gone by the seventh ballot. Massachusetts delegate George Bancroft offered Speaker of the House James Knox Polk as a running mate for Van Buren or Stewart. Polk’s supporters vowed to endorse Stewart if he selected Polk as his vice president.

The matter was offered to Stewart at a dinner. He said nothing, appearing unusually nervous and fidgety. This was the moment of decision. If he turned them away, there would never be another opportunity and he would return to his estate in Bordentown to live out his days as the chance for another sea command – particularly as he had already been commodore of the Mediterranean, Pacific and Home Squadrons – was unlikely.

“If nominated,” he finally said, “I will accept.” His nomination was immediately reported by Samuel Morse’s new telegraph.

With Jackson’s protégé, Polk, by his side, and the delegates from Pennsylvania and New York committing to the ticket, the northern and western states soon followed suit. The sixty-six year old Stewart provided a heroic narrative for the newspapers, much as Jackson’s army experience had vaulted him into the presidency. In the general election, Polk’s Tennessee roots offset Clay’s enough for Stewart to be elected president.

Though his vice president kept pushing an agenda to annex Texas and secure the northwestern territories, Stewart was resistant to fighting on too many fronts for a nation with a small army and navy. He named his friend and navalist James Fenimore Cooper Secretary of the Navy, a move not unprecedented since another of the literary Knickerbocker Group James Kirke Paulding, had held the same position under Van Buren. Cooper’s extensive non-fiction writing in the previous decade about building up the fleet convinced Stewart that he was the right man for his administration. Stewart focused his administration on building and modernizing the navy and providing new markets for the merchant fleet. Westward expansion held no interest to the sailor-president.

Naming Matthew Perry America’s first admiral, Stewart had read his 1839 report on the navies of Europe. A young French ship designer had also come to his attention. The days of wooden frigates and ships of the line designed by Stewart’s former colleagues, the Humphreys, were passing. Stewart realized that the country had to make a leap forward if it was to become a great power. He hired Henri Dupuy de Lome, a French ship designer proposing an iron-hulled-screw-driven frigate. Together with Commodore James Barron, who had designed a steam-powered tri-hulled ram ship in the 1830s, and a young engineer Charles Ellet proposing his own ram ship, the team built a new naval force.

In late 1845, Stewart sent his Secretary of State Richard Rush, a former Minister to Great Britain, to issue demands of the British Empire including accepting U.S. terms on the Oregon Territory. Rush and Stewart alone remained from their Philadelphia schoolyard from where two other friends perished – first Richard Somers at Tripoli and then Stephen Decatur in a duel. Stewart built a coalition of those defeated by the Royal Navy that had allowed it to rule the seas. Spain had a small navy with some ships that remained in harbor since the days of Trafalgar. But France offered Stewart more hope.

In 1836, Louis-Napoleon, the nephew of Bonaparte, had attempted a coup. Failing that, he sailed for the United States. He met in New York with the elite including generals and naval officers. He vowed to poet Fitz-Greene Halleck – one of the Knickerbockers – that he would become Emperor. He was welcomed at the Naval Lyceum at the Brooklyn Navy Yard then he traveled to Bordentown where his uncle Joseph – the dethroned King of Spain – had exiled himself. Here Louis-Napoleon became acquainted with Stewart and his family. Stewart funded Napoleon in 1845 to overthrow the government then sent his own son, Charles Tudor Stewart, as emissary to the throne of Napoleon III.

England rebuked Rush and when he returned, Stewart asked for a declaration of war.

Queen Victoria, Prime Minister Robert Peel by her side, sent the British Fleet under the aged Admiral of the Fleet James Hawkins-Whitshed off to the Americas to put the upstart nation down quickly, lest other nations be inspired by their defiance. The Royal Navy hadn’t been defeated in forty years and its wooden walls would not fail now. Its objective was the Chesapeake Bay where transport ships would land in Norfolk, Baltimore, and up the Potomac River to Washington.

A recognized Constitutionalist, Stewart had averted a war with Algiers in 1805 when he pointed out to the squadron’s Commodore that only Congress could declare war and again in 1815 when notified that the Treaty of Ghent had been signed pressed the crew of the Constitution to continue its wartime footing since only the Senate could ratify a treaty – and there had been no such news. It allowed him just a few weeks later his greatest victory of the USS Constitution over the HMS Cyane and HMS Levant. Now, he followed the Constitution again while anti-British fervor in Congress overwhelmingly supported a third war for American independence and reduce England’s control of the oceans and the trade it dominated. He also knew Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution which stated that the President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy. He would lead the fleet.

Perry objected as the honor should have been his as Admiral until Stewart divided the fleet. One squadron under Perry steamed south from Baltimore toward Norfolk. The English fleet of nearly one hundred ships sailed slowly into the mouth of the Chesapeake toward the unmistakable plumes steamships to the north. Stewart’s fleet waited in Gosport. Thirty years before, Stewart was in command of USS Constellation and was prevented from getting underway because of Admiral Sir John Warren’s squadron. This new British fleet had several steamships, but no ironclads. Unfortunately the British, who had always been prone to overpowering their ships at the risk of maneuverability, sent their expedited screw-propelled ships-of-the-line like the QUEEN and ALBION classes at the head of the fleet.

Perry’s squadron was the first to fire upon the fleet while Stewart’s squadron of iron-clad ram ships steamed east into the heart of British fleet. Ships of the line and frigates were holed one after the other while others fell to Perry’s barrage. A quarter of the fleet, including most of the transports, tried to escape to the Atlantic, but soon encountered a joint French-Spanish fleet at the mouth of the Chesapeake. The remaining ships surrendered without firing a shot. In just a few hours with the Battle of the Chesapeake, Stewart had achieved the greatest maritime victory since Trafalgar.

England soon sent diplomats to negotiate a peace. During negotiations, Stewart provided aid to his son-in-law, John Parnell, to foster a rebellion in Ireland as Napoleon III became more active in the English Channel. The Peel government acquiesced to Stewart’s primary demand and lost not only claims to the Oregon territory but all of Canada. Stewart had doubled the size of the country in a short war, secured a western coast for the country with additional ports, increased the number of free states, and assured additional pro-Stewart members of Congress in the 1846 election.

Stewart was able to turn to domestic issues, particularly that of slavery which continued to politically divide the country. With the addition of the new northern states, Stewart had enough support in Congress to outlaw slavery, fomenting revolt in the South. Stewart averted a civil war by listening to his vice president who for years had been advocating Texas annexation and a war with Mexico.

Encouraged by Stewart’s stance, Napoleon III launched an invasion of Mexico claiming the right of free trade was being denied by President Farias and then Santa Anna. Stewart announced support for France as he ordered squadrons to support US operations in Texas and California. After a long-standing feud with General Winfield Scott (Stewart’s marriage of proposal to Maria Mayo, Scott’s eventual wife, was rebuked,) Stewart appointed General Zachary Taylor to command the Army.

Within two months, the US controlled all of Mexico’s territory north of the Rio Grande while France controlled all territories to the south. The final battle occurred outside Mexico City where the French defeated and killed Santa Anna on the fifth of May, 1847, a day still celebrated in 21st century France as “Cinque de Mai.” With this war concluded, Stewart dispatched a squadron under Commodore John Aulick to open trade with Japan and expand trade with China.

After the First Franco-American Coalition War, Stewart knew he could not avert a civil war with pro-slavery and states’ rights forces demanding that Texas and the new territories become slave-holding states. While Congress debated the Great Compromise of 1848, Stewart took preemptive action and sent the fleet under Commodore David Conner to secure southern ports and Admiral Perry into New Orleans to take the Mississippi River. Taylor took his army and advanced them on all federal arsenals and depots before the southern states could organize.

The south began a guerilla campaign led by a young hero of the Coalition War, Robert E. Lee. But Lee, an engineer accustomed to large troop operations was either by temperament or experience unable to conduct the only warfare option available to the south. Within four months, Lee’s Raiders and their associated militias were captured with the loss of nearly one thousand Union troops. Stewart was criticized for such a costly operation but soon found favor from both the north and south with the Stewart Proviso. A delegation composed of Stewart, Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, Lewis Cass, Stephen Douglas, and Nicholas Trist, agreed that: 1) slavery would be abolished in the United States, 2) any freed slaves would be offered five acres of land in the new Canadian states, 3) federal occupation of the port cities would end, and 4) the former slave states would receive exclusive trade rights due to the recent agreements in southeast Asia.

Having gained control of most of North America fulfilling his party’s dreams of Manifest Destiny, diminishing the role of the world’s superpower, increased America’s geopolitical position, and enriching the country – particularly the South which enjoyed unprecedented riches, enabled Stewart to easily defeat his opponent in the 1848 election, the Whig nominee Winfield Scott. The Free Soil Party dissolved before the election because of the resolution of slavery.

His first term marked by rapid military operations and overtures to both Europe and Asia, Stewart’s second term soon took advantage of the European Revolutions of 1848. Stewart’s son-in-law John Parnell took control of an independent Ireland as his wife gave birth to their son, Charles Stewart Parnell. Stewart formed global squadrons to secure America’s interests and expand commerce in South America and Africa as European powers yielded what little control they had in the wake of the revolutions.

In 1852, the seventy-four year old chose to run for a final, third term. James Fenimore Cooper remained one of his closest cabinet members and penned a major treatise on the American navy’s global imperative. The tome was advanced by Stewart in his third inaugural address and embraced by Congress which supported the Naval Expansion Act of 1853 assuring construction of the largest fleet in the world and ensuring global security for nearly sixty years.

Claude Berube is the co-author of “A Call to the Sea: Captain Charles Stewart of the USS Constitution” and has taught in the Political Science and History Departments since 2005. His latest novel, “SYREN’S SONG,” will be published in November by Naval Institute Press.