By Jimmy Drennan

Introduction

Some were surprised by the news that four U.S. soldiers were killed in an ambush in Niger and may have even wondered “why do we have troops in Africa?” Some also agree with the recent bipartisan call from Congress to end U.S. military support to the Saudi Arabian-led coalition’s intervention in Yemen. In this context, the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb, the narrow waterway between the Arabian Peninsula and northeast Africa, might sound inconsequential, but is in fact critical to U.S. national security interests.

Arabic for “the Gate of Tears,” the strait could not be more appropriately named. Situated at the center of the some of the world’s most critical humanitarian disasters and economic issues, it is a decisive point for U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East and the global economy more broadly. To the north lies Yemen, a failed state where 17 million people face starvation, over a million people are stricken with cholera while thousands have died from the disease, a diphtheria outbreak has emerged, and multiple regional actors and terrorist networks vie for power in a bloody conflict that has claimed over 5,000 civilian lives in three years.

To the south lies Africa where fragile states like Somalia battle famine and Islamic militant groups. Atrocities abound at sea as well. Refugees cross the Bab-el-Mandeb to the north and south because both sides seem to be the better alternative. In March 2017, 42 refugees fleeing from Yemen to Sudan were shot and killed by an attack helicopter, which apparently mistook them for militants.1 In August 2017, smugglers threw over 300 Somali refugees into the water near the Yemeni coast, drowning up to 70, in the span of 24 hours after reportedly sighting authority figures on shore.2 Just last week, 30 African refugees drowned en route from Aden to Djibouti, after their boat capsized amid gunfire from smugglers.

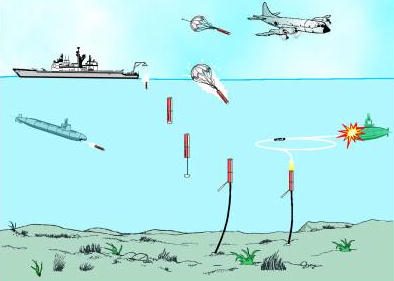

Meanwhile, the Bab-el-Mandeb serves as a critical artery for the global economy. 52 vessels and 4 million barrels of oil transit the strait per day, making it the fourth busiest waterway in the world, and the only one surrounded by chaos. In the last year, two merchant vessels and five naval ships have been attacked with cruise missiles, explosive boats, and small arms in the southern Red Sea, while the very real threat of mines exists lurking in the water.

Yemeni and Somali civil wars, humanitarian disaster, and the economic importance of the Bab-el-Mandeb form a complex dynamic in which to develop U.S. foreign policy. The key for policymakers is to determine what U.S. national interests are at stake and what actions must be taken to protect them. After careful consideration of the issues surrounding the Bab-el-Mandeb, it becomes clear that the U.S. can ill afford to do nothing. On the other hand, it may also be unaffordable to secure U.S. interests by leading multilateral stabilization efforts via intervention within Yemen and Somalia. Fortunately, a third alternative is available via American seapower. Applying maritime influence to enable other elements of national power can contain threats to national security and the global economy, while providing a path to mitigate human suffering in the long term.

U.S. National Interests and the Strategic Calculus

The debate over U.S. national interests will not be settled here, but for simplicity’s sake and the purpose of meaningful analysis, the following definitions from the July 2000 Commission on America’s National Interests will be used:3

- Vital – Vital national interests are conditions that are strictly necessary to safeguard and enhance Americans’ survival and well-being in a free and secure nation. A key example is to “ensure the viability and stability of major global systems (trade, financial markets, supplies of energy, and the environment).”

- Extremely Important – Extremely important national interests are conditions that, if compromised, would severely prejudice but not strictly imperil the ability of the U.S. government to safeguard and enhance the well-being of Americans in a free and secure nation. A key example is to “Prevent the emergence of a regional hegemon in important regions, especially the Persian Gulf.”

- Important – Important national interests are conditions that, if compromised, would have major negative consequences for the ability of the U.S. government to safeguard and enhance the well-being of Americans in a free and secure nation. A key example is to “discourage massive human rights violations in foreign countries.”

Due to the importance of the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait to the global and, consequently, U.S. economies, the U.S. has a vital national interest in maintaining the free flow of commerce through the Strait. Even if the U.S. did not depend on the 1.5 billion barrels of oil (currently $98B) annually that flow through the Strait, allies in Europe would certainly feel the economic impact if shipping companies re-routed their vessels around the Cape of Good Hope in the event of crisis or conflict. Inflated maritime insurance rates and an additional 10 days transit time from the Middle East to the U.S. would have considerable worldwide ripple effects to which the U.S. economy would not be immune. Moreover, as one of two primary sea lines of communication to the CENTCOM AOR, the U.S. also has a military interest in maintaining freedom of navigation through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait. In October 2016, the U.S. was forced to respond with Tomahawk missile strikes into western Yemen when the USS Mason came under anti-ship missile fire from the Yemeni coast. Further attacks would increase risk and necessitate additional escorts for Bab-el-Mandeb Strait transits.

Conversely, the U.S. has no vital national interest in broader involvement in the armed conflicts in Yemen and Somalia; however, its interests are clearly impacted by the growing threat emanating from Yemen. In western Yemen, Saudi Arabia along with eight other regional allies, are fighting a brutal war against separatist Houthi rebels who aim to establish an anti-Western Shia government in Yemen. In December 2017, U.S. Ambassador Nikki Haley provided material evidence to the international community that Iran provides missiles and advanced weaponry to the Houthis, enabling them to target vessels transiting the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and strategic locations inside Saudi Arabia, threatening the U.S. national interest in free flow of commerce and advancing its own interest in promoting its regional hegemony.4,5 In January 2018, the Houthis threatened to close the Red Sea to international shipping if the Saudi-led Coalition continued its advance toward Hudaydah, a strategically important Houthi-held port critical to the flow of humanitarian aid. If the Houthi threat is credible, Iranian-aligned forces could now threaten another vital maritime chokepoint, in addition to the Strait of Hormuz which Iran has often threatened to close. Growing Houthi influence and capabilities in Yemen also impose costs and shift the balance of power in relation to Iran’s regional opponents, primarily Saudi Arabia, and allows Tehran to expand its influence elsewhere. Saudi Arabia may have felt compelled to intervene in Yemen’s civil war as the tide shifted in favor of the Houthis because the prospect of bordering an Iranian-aligned state would prove strategically disadvantageous.

In eastern Yemen, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and ISIS-Yemen maintain presence, despite UAE-led counterterrorism operations, due to lack of effective governance and internal security. Despite pressure from the West, AQAP remains a threat to the U.S. homeland, and the prominence of ISIS-Yemen continues to grow as the extremist caliphate is gradually eliminated in Iraq and Syria. Without a doubt, the U.S. has a vital national interest in supporting its Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) partners in their counterterrorism efforts and in defense of their borders, but it does not benefit from becoming directly entangled in the fight.

Similarly, Somalia provides a safe haven for terrorists who would do harm to U.S. interests at home and abroad. Fighting rages on between the Federal Government of Somalia, which was only recently established after two decades of near-anarchy, and the Al-Qaeda aligned militant group Al Shabaab, while the civilian population suffers the consequences. Meanwhile, criminals continue to recruit disenfranchised young men, desperate and angry with perceived (and sometimes real) illegal fishing in Somali territorial waters, to become pirates. Still, even though Somalia is a hallmark of instability in the region and a safe haven for terrorist organizations, the U.S. has no vital national interest in establishing security and governance in the African country. From Vietnam, to Somalia itself in the 1990s, America has learned through experience the high cost of entering into regional and internal armed conflicts in proxy pursuit of national interests. Becoming directly entangled in the conflicts surrounding the Bab-el-Mandeb is counter to U.S. national interests, but so is ignoring them. U.S. vital national interests in Somalia and in Yemen are limited to ensuring instability is contained within territorial borders so that the free flow of commerce is maintained, attacks against the homeland and assets abroad are prevented, and American influence in the region is sustained.

In Pursuit of National Interests

Considering U.S. vital national interests in the Bab-el-Mandeb and surrounding territories – maintaining the free flow of commerce, preventing attacks against the homeland and assets abroad, and sustaining American and allied influence in the region – the challenge arises when deciding how to apply the instruments of national power (diplomatic, informational, military, and economic) to secure those interests. The U.S. could secure its interests by:

1) Leading a large-scale multilateral stabilization effort for Yemen and Somalia

2) Containing threats to national interests via maritime influence; or

3) Taking no action (Isolationism)

Option 1: U.S.-led Stabilization Effort

Bringing all instruments of national power to bear on the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait by leading multilateral stabilization efforts in Yemen and Somalia is a thorough, long-term approach to securing U.S. national interests; however, it would come at significant cost. Securing national interests via stabilization could involve, in varying degrees: state building, military intervention, occupation, and inevitably comparisons to “neo-imperialism” and “adventurism.” In theory, these activities could give rise to effective governance, which would serve to eliminate the threats to U.S. national interests spilling out of Yemeni and Somali borders. The governments, in this case the Federal Government of Somalia and Republic of Yemen Government, ideally would be able to aid in securing the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, stamp out terrorist safe havens, and provide adequate food and medical care to their populations, all while acting in alignment with U.S. foreign policy objectives.

The trouble is that stabilization has rarely turned out the way the U.S. intended. The most striking examples are Iraq and Afghanistan, where the U.S. remains after intervening to eliminate threats to the homeland and the region. Supporting Contra rebels in Nicaragua in the 1980s or the present-day Syrian Opposition are two examples where the U.S. applied pressure indirectly with less than desirable results. Meanwhile, it’s been 25 years since the U.S. first led a UN coalition into Somalia, tasked with stabilizing the war-torn country whose central government had collapsed. Clearly, stabilization efforts are no sure thing. Even when stabilization is successful, the cost is immense. Following World War II, in addition to the over $14B ($140B in today’s dollars) given in aid to Germany and Japan for economic recovery, the U.S. maintained a significant military presence to help stabilize those countries.6,7 It is reasonable to assume that a concerted effort to stabilize Yemen and Somalia would lead to indefinite military presence in those countries as well. Fortunately, there is an alternative to stabilization for securing U.S. national interests in the Bab-el-Mandeb region: maritime influence.

Option 2: Containing Threats to Yemen and Somalia – Maritime Influence

Rather than directly stabilizing Yemen and Somalia, the U.S. can ensure the free flow of commerce and secure its foreign policy objectives in the region by exerting maritime influence and projecting its power landward. Through a combination of naval operations, international cooperation, and engagement with industry, the U.S. can mitigate the risk to commercial and friendly naval vessels transiting the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, albeit not without the presence of forces as a credible deterrent to would-be attackers. Securing the critical waterway can help secure U.S. foreign policy objectives in the region by eliminating maritime attacks as an option for belligerents in internal conflicts and forcing their attention inward, but airstrikes or other direct action may be required to drive home the point that the Bab-el-Mandeb is “out of bounds” and the consequences for attacking neutral parties are severe. Ultimately U.S. maritime influence could contribute to international pressure to peacefully end the Yemeni Civil War, and fortify the fragile Somali government. Meanwhile, maritime assets could act as seabases for forces providing humanitarian aid or conducting raids on terrorist networks. The agility the Navy provides – in the form of hospital ships, aircraft carriers, amphibious ships, various surface combatants and patrol craft, sealift and logistics ships, landing craft, helicopters, and other aircraft – has been on display in disaster relief efforts such as the Indonesia tsunami in 2004 and the Haiti earthquake in 2010. These same assets can be used to support counterterrorism efforts as expeditionary mobile bases, allowing special forces to conduct short-duration operations with minimal footprint on land. Lastly, interdiction of lethal aid flowing into Yemen, enabled by UN Security Council Resolutions, would be a key element of maritime influence.

International maritime operations are already underway in the region that the U.S. could leverage to build a maritime influence strategy. U.S., allied, and other international navies, such as China, Russia, and Iran, maintain presence in the Gulf of Aden. These navies already work with organizations such as the U.S. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and U.K. Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO) to advise industry of potential threats to shipping. The key to success of a maritime influence strategy will be cooperation of these international navies, especially since the U.S. cannot afford to take on this security burden alone. The U.S.-led Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) offers a viable model for bringing to together naval forces of 32 countries, some of whom would not normally form military partnerships with each other, to provide maritime security in the Middle East. Mutual participation of both Saudi Arabia and Iran, although seemingly unlikely, should be a goal for U.S. policymakers, as this could set the stage for dialogue to mitigate the humanitarian crisis in Yemen. Additionally, contrary to conventional U.S. foreign policy, U.S. leaders should consider recognizing Iran for their contribution to international counter-piracy efforts off Somalia, while holding Saudi Arabia accountable for their role in contributing to the devastating humanitarian conditions in Yemen.

The international campaign to combat the Somalia piracy epidemic in the early 2000s provides an ideal example of how maritime influence has been proven to effectively eliminate threats at sea. From 2005 to 2012, pirates attacked nearly 700 ships in the Somali basin, and collected $400M in ransom payments. Over that time, the international community gradually came together to address the problem. The U.S. established a multinational maritime coalition to counter piracy threats, and participated in EU and NATO task forces as well. As many as 20 international warships patrolled the waters around the Horn of Africa at any given time. Simultaneously, the U.S. coordinated with the International Maritime Organization (IMO) to establish a set of industry best practices, the latest of which, Best Management Practices, Rev. 4 (BMP4), officially endorsed unarmed embarked security teams.[8] Other maritime influence efforts included establishing an internationally recognized transit corridor, real-time vessel tracking and communication with maritime agencies, and development of mechanisms for transfer of detained pirates to cooperative local governments. This international effort to push piracy back to land was effective – pirates did not successfully hijack a single vessel in the Somali Basin from 2013 to 2016. It is important to note, however, that piracy will remain a threat until it becomes cost prohibitive. Criminals still take advantage of poverty and conflict in Somalia to recruit disenfranchised young men. In 2017, a series of six attacks raised concerns that the piracy epidemic had returned. Instead, it turned out that industry had become lax in applying best practices and about half as many warships patrol the area as in 2012. Not coincidentally, NATO concluded its counter-piracy operation in December 2016. Pirates seemingly sensed an opportunity. Fortunately, no ransoms were paid and the international community once again applied maritime influence to beat back the piracy threat.

Maritime influence was effective in pushing piracy back to shore, and it essentially removed piracy as an option for financial gain in Somalia. In fact, judging from the improvements in Somalia over the last decade, from growing GDP and livestock exports and a democratic presidential election in 2017, one could argue that maritime influence contributed to better conditions on land. Still, the root conditions in Somalia that led to the problem in the first place persist. Maritime influence is not a foreign policy panacea. In the Bab-el-Mandeb region, the U.S. would need to apply maritime influence while supporting international stabilization efforts to make meaningful progress toward resolving the humanitarian crises in Yemen and Somalia, eliminating terrorist safe havens, and effectively securing its national interests. Thus, the U.S. still risks becoming entangled in foreign wars. The U.S. needs to consider whether investing in the security of Yemen, Somalia, and the Bab-el-Mandeb is worth the cost. Of course, the third option is to invest nothing and accept the potential consequences.

Option 3: Isolationism

It can be tempting to assume the U.S. should do nothing at all to stabilize the region around the Bab-el-Mandeb, especially amid the rising tide of nationalism and isolationism in America. After all, many argue that the U.S. should withdraw from the Middle East completely. The danger is that the humanitarian crises in Yemen and Somalia may reach the point of catastrophe, at which the U.S. could be compelled to act purely on the basis of respect for humanity. On a grand enough scale, the alleviation of human suffering, much like the prevention of genocide, can in fact be a vital national interest. There are already 20 million people starving and over one million people suffering from cholera and diphtheria in the two countries surrounding the Bab-el-Mandeb, an unparalleled concentration of human suffering. A particularly heavy rainy season, or even a single cyclone, could rapidly exacerbate shortages of food and medical care. At some point, the loss of life could become so immense that the U.S. has no choice but to intervene, regardless of its security or economic interests. Such an intervention would inevitably come at great cost in terms of dollars and foreign policy objectives, not to mention the risk to American armed forces and civilians on the ground.

Another consequence of doing nothing to stabilize the region is the power vacuum that will likely continue to grow. In Yemen, AQAP and ISIS will unquestionably continue to plot and orchestrate attacks against U.S. interests, barring a concerted U.S. or international effort. In Somalia, the U.S. and other allies provide military support to the government’s fight against Al Shabaab and other militant groups. Without American involvement, both countries would be safe havens for those who would do Americans harm. Further, wherever the U.S. has withdrawn presence and influence throughout the Middle East, states such as Iran, Russia, and China predictably increased their operations in those areas. In August 2017, China opened its very first overseas naval base just south of the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait in Djibouti, signifying the strategic importance China places in the region. With American withdrawal, the U.S. and global economies would be dependent on foreign efforts to secure the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, whatever those may be. In any case, increasing maritime threats may inevitably force the U.S. foreign policy hand, only the response would be reactive instead of proactive, dictated by the enemy’s actions.

Conclusion

The U.S. can afford neither to ignore the threats emerging from the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and surrounding territory, nor can it afford to aggressively intervene in Yemen and Somalia wholesale to fully stabilize the region. The most affordable approach to securing U.S. interests in the region is through maritime influence to enable regional and international partner efforts. By leading an international naval, diplomatic, and economic campaign, augmented with key activities internal to Yemen and Somalia, the U.S. can ensure the free flow of commerce, prevent attacks on American citizens, and preserve its influence in the region, while setting the stage for resolution of internal conflicts and humanitarian crises. It may seem heartless to take such a calculated approach to secure one’s own interests in the face of so many others’ suffering. It is helpful, however, to consider that the best way to mitigate that suffering and secure U.S. national interests may be one and the same. Under the wholesale intervention and stabilization approach, humanitarian conditions will not improve at all unless the U.S. is willing and able to adequately resource an international effort, which seems unlikely. Stabilization of Yemen and Somalia through U.S. intervention is simply not a feasible option. The U.S. may not be able to keep the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait from living up to its Arabic name, “the Gate of Tears,” but the best approach to securing its national interests, by exercising maritime influence, also happens to represent the best opportunity to positively impact humanitarian and security conditions in the long run without risking excessive entanglement.

Jimmy Drennan is the President of the CIMSEC Florida Chapter. These views are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of any government agency.

CIMSEC is committed to keeping our content FREE FOREVER. Please consider donating to our annual campaign now so we can continue to provide free content.

References

[1] Beaumont, Peter (17 March 2017). “More than 40 Somali refugees killed in helicopter attack off Yemen coast.” The Guardian. Retrieved 24 Aug 2017.

[2] UN News Centre (10 August 2017). “Smugglers throw hundreds of African migrants off boats headed to Yemen – UN.” United Nations. Retrieved 24 Aug 2017.

[3] Ellsworth, Robert, Andrew Goodpaster, and Rita Hauser, Co-Chairs (July 2000). “America’s National Interests: A Report from The Commission on America’s National Interests, 2000.” Commission on America’s National Interests.

[4] Tillerson, Rex (19 April 2017). “Secretary of State Rex Tillerson Press Availability.” U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 24 Aug 2017.

[5] AFP (25 August 2016). “Iran arms shipments to Yemen ‘cannot continue’: Kerry.” AL-MONITOR. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

[6] U.S. Department of State Historian. “Milestones: 1945–1952 – Office of the Historian”. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

[7] U.S. Bureau of the Census. “Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1954 (1955),” table 1075 pp 899-902.

[8] The U.S. officially recommends armed security teams.

Featured Image: Bab-el-Mandeb Strait (via Eosnap.com)