By Ryan Hilger

“There’s a good chance…we’d lose the opening stages of this war,” remarked one high ranking official at a recent conference on Multi-Domain Operations.1 Many senior officials are rightly worried that our potential adversaries have spent the last fifteen years developing capabilities tailored against us as while the U.S. military has been focused on Afghanistan, Iraq, a plethora of other low-intensity operations occurring all over Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, and perpetually overdrawn budget. Staffs in the Pentagon and at the systems commands fret over how we will maintain, much less expand, our competitive advantage as these countries undertake very public campaigns to develop capabilities such as hypersonic weapons and artificial intelligence.

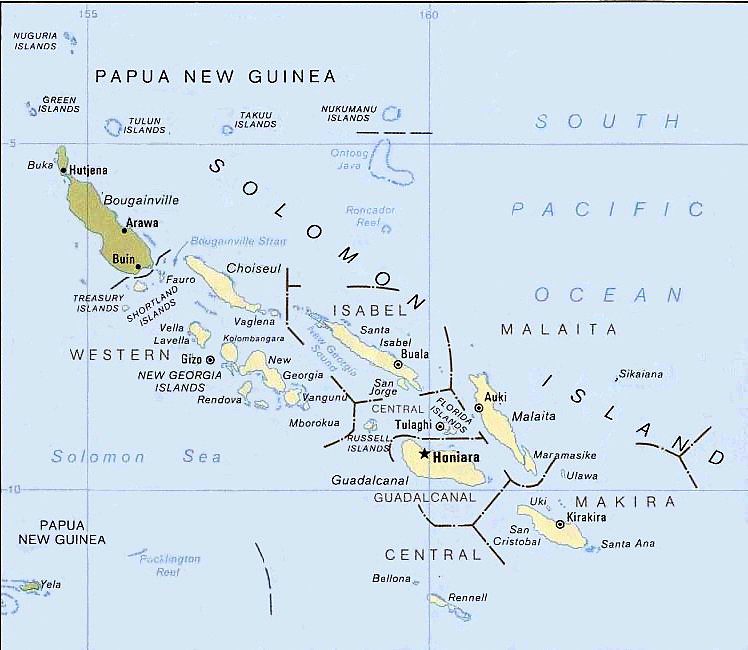

Lost in the moment it is easy to forget that we have been in a similar situation before in the 1930s and 1940s. During the interwar period, the Fleet Problems were strategic proving grounds and tactical classrooms, incubating revolutionary tactics such as carrier warfare. The Navy refined those strategies in the crucible of World War II, and the lessons from those campaigns, not just the battles, are key to maintaining operational superiority in a new era of great power competition. Admiral Scott Swift, while the Commander of U.S. Pacific Fleet, reinstituted Fleet Problems to prepare the Navy for the high-end fight using the tools on hand today.2 Taking the Fleet Problems to the next level by including our joint forces will yield greater dividends and prepare the Navy for fighting campaigns, not just battles—something we haven’t done since World War II.3 Conducting the next one in the Solomons will reinforce the lessons of the campaign there in 1942 and stress the harsh, indiscriminate effects of geography on prolonged maritime campaigns.

Maritime Parallels and Analogues

China, like Japan in the 1930s, seeks to be a major regional, if not global, power. China continues to expand its presence and capabilities in the South China Sea, recently established a naval base in Djibouti, and begun making overtures to Vanuatu in the South Pacific.4 The Chinese, always with the long view, have embarked on a campaign to protect their global supply lines which are needed to fuel their industrializing economy. The Philippines, traditionally an American stalwart, openly denounced ties with us and moved directly toward Beijing.5 This sounds familiar. As early as 1931, the Japanese began pushing out into the same waters, seeking natural resources for their growing economy. By 1941, the Japanese had secured their western and northern fronts with campaigns in China and Manchuria, signed a pact with Russia, and established strong naval bases in the Marshall, Marianas, and Caroline Islands.6 Japanese naval power grew stronger by the day.

The conditions were becoming ripe for further expansion to secure their sea lines of communications and expel all western influence in Asia. After the war, the Japanese told an American survey team that their strategic plan for conducting the war against the Western powers was initially to be a “series of simultaneous and overwhelming surprise attacks on all of the Pacific bases of the western powers.”7 They succeeded brilliantly. The Japanese push to the their second island chain—both through the Marshalls and Gilberts toward Samoa, and through the Solomons with the capture of New Guinea as the final stroke—was predicated on the strategic desire to interdict supply lines between the United States and Australia, provide a defense-in-depth for maritime resource flows back to Japan, and to fight the remnants of the American Navy far from their shores. The same is true of Australia and its pivotal relationship to a Pacific campaign today.

The geographic conditions are eerily similar to China’s expansion today, and the “range, lethality, and sophistication of [their] new anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities constitute an unprecedented array of A2/AD capabilities that threaten the U.S. model of power projection and maneuver.”8 Additionally, today’s fiscal constraints, aging force structure, and readiness issues lends credence to the fear that the United States and its partners could be overrun in the opening phases of a conflict, just as it was almost eighty years ago with near-simultaneous defeats at Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, Wake Island, and the Java Sea. The subsequent campaign through the Solomons provides many lessons to inform maritime strategy today. Understanding these lessons requires a shift away from celebrating Mahanian naval battles, like Midway, to embracing the need to fight prolonged, joint campaigns to deter aggression or regain access.

Island Chains and the Maritime Siege

Nowhere is the tyranny of distance felt more than in the Pacific. This was true in 1942 and it is just as relevant today. Coming from Asia, both the Japanese in the 1940s and the Chinese today have a number of stepping stones to project power, are able to create overlapping barriers to deter and attrite forces moving west, whether as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere in the 1930s or the Chinese Nine-Dash Line claims today. Captain (Ret.) Sam Tangredi identified these attritional operations as one of the central elements of an anti-access strategy.9 To this he adds four more: perception that the attacking force is superior; the maritime domain is the dominant conflict space; information, intelligence, and deception are critical and; unrelated events elsewhere have a decided impact.10 The Pacific theater, then and now, has many of these elements in abundance.

The Japanese followed up on their successes of December 1941 with a series of rapid offensives through the south-central Pacific, sweeping aside nearly all allied garrisons in the process. At the outset, Admiral Yamamoto believed the American Navy was superior and needed to be reduced before giving in to a decisive battle. Lawrence Freedman notes that the Americans knew that an early attack was probable, but only looked to “the Philippines as a target and had underestimated Japanese capabilities. They had assumed that the strength of the Pacific Fleet would serve as a deterrent.”11

In late January 1942, the Japanese pushed through the Bismarck Archipelago in the southern Pacific and seized a major objective at Rabaul.12 The development of Rabaul would be critical in flowing forces into the region to extend Japanese power into the Solomons and threaten allied supply lines to Australia.13 Subsequent Japanese Army operations in the region developed mutually supporting bases. Chinese movement toward Vanuatu today appears quite similar to the Japanese moves in 1942. Chinese port infrastructure projects in Vanuatu will be able to support warships once complete and the development of Chinese naval presence there would represent a major threat to both intercontinental supply lines and any naval forces moving through the region—the foundations of an anti-access strategy. However, in War Plan Orange, Miller notes that distance, so onerous for the United States to overcome, would prove a fickle mistress for the Japanese should Americans penetrate the barriers and establish advanced bases, giving it the ability to “sever Japan’s trade lifelines, neutralize its outlying stations, overwhelm its fleet in battle, and bombard its homeland. Defeat would follow inevitably.”14 The same could be said in a protracted conflict with China today.

Joint Maritime Campaigns

The Battle of Midway brought the American Navy its first true victory of the war, but it was not the decisive battle of the war. As both navies recovered from the losses sustained, Admiral Nimitz knew that the Japanese buildup in the Solomons had to be stopped and that the course of the next campaign would decide the war. The allied forces had to take the offensive to gain the initiative. In just over one month’s time, American forces planned, organized, and executed Operation WATCHTOWER, or as it was better known given the dearth of resources afforded it, Operation “Shoestring.”15 The next four months following the amphibious landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi on August 7, 1942 would prove pivotal and decisive.

American surface forces had yet to meet their Japanese counterparts in battle. The ferocious fighting in and around the Solomons, a true back and forth affair, shows the grind of the campaign and the absolute necessity for the campaign to be joint. The American Navy could not have won it alone then, nor, as Admiral Swift asserts, will we be able to do so in a future conflict.16 Taking a solely naval perspective of the Solomons campaign would fall into Rear Admiral Joseph Wylie’s strategic trap, in that “[t]oo often the first or blue-water phase of maritime strategy is regarded as the whole process rather than no more than the necessary first half.” The second phase, after adequate sea control is established, is “the exploitation of that control by projection of power into one or more selected critical areas of decision on the land.”17 Our fleet must necessarily remain aligned with our national objectives, supporting other operational campaigns by our joint partners, which force a decision of our adversary on land—neither the Japanese nor Chinese navies can capitulate on behalf of the national government should they choose to continue resisting. Thus, the success of the Marine and Army effort to secure Guadalcanal rested directly on the joint maritime campaign to keep them from being overwhelmed.

The Japanese held a formidable position in the South Pacific. The Solomon Islands were within range of land-based aircraft and naval forces from Rabaul, Buka, and other bases, which could all be quickly reinforced from Truk. Combinations of these forces could deny the seas around Guadalcanal nearly around the clock. American land-based airpower—Army B-17s based at Espiritu Santo, Efate, and Port Moresby—could only provide marginal support, and the aircraft carriers had to steam within range of Japanese air power to effectively use their air wings. The amphibious forces of Task Force 62 under Admiral Kelly Turner, which needed several days of continuous unloading operations, would be exceptionally vulnerable until the airstrip on Guadalcanal could be made operational. Admiral Frank Fletcher, commanding Task Force 61, believed that he could only risk the carriers that close to Guadalcanal for three days at most before the likelihood of Japanese attack was too great to continue. Events forced them to withdraw after only two.18

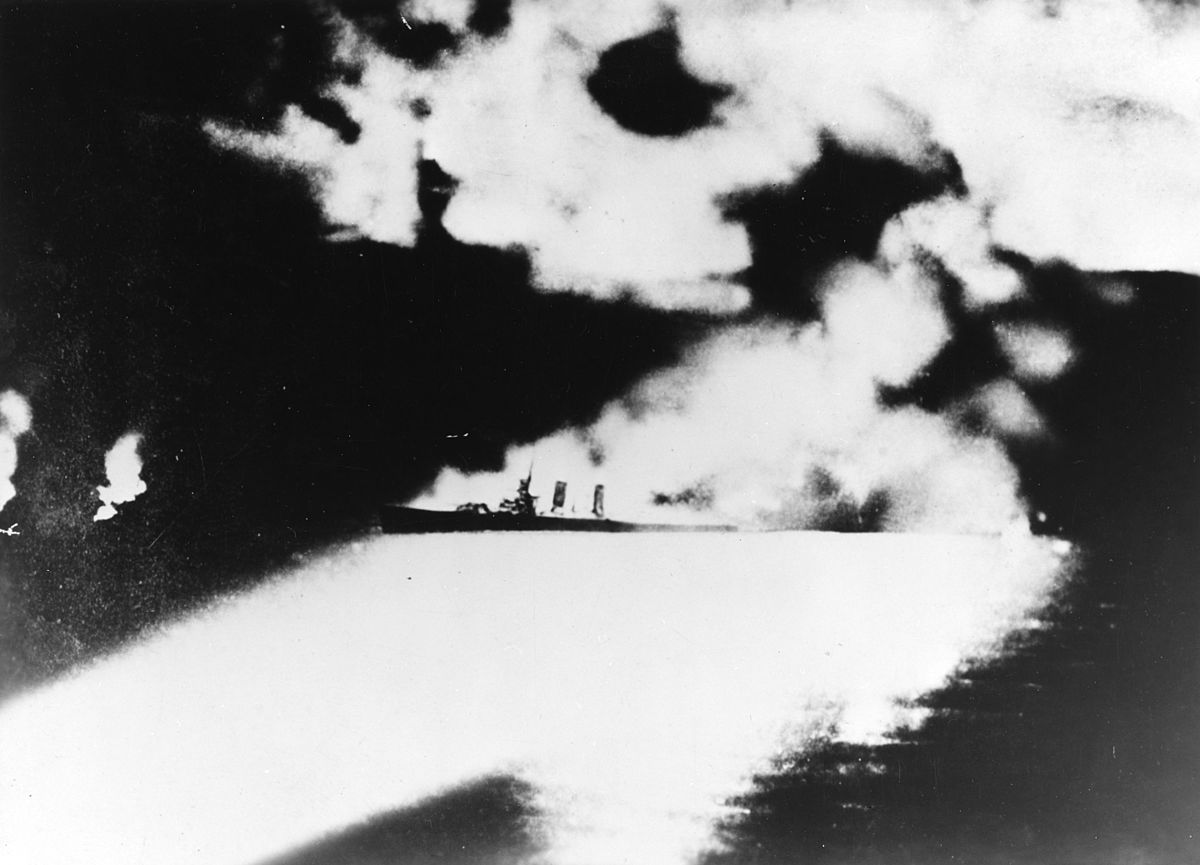

The Japanese, though surprised, responded rapidly. American surface forces patrolled the waters to the north of Guadalcanal near Savo Island, protecting the landing forces. On the night of August 8th, Samuel Eliot Morison writes:

“Sailors onboard the cruisers were still talking of their performance during the two days past. They had helped the Marines to land by chasing Japs into the hills with 8-inch shells; they had protected the transports with anti-aircraft fire. But they were dog-tired after two days of incessant action and excitement…It was a hot, overcast and oppressive night, ‘heavy with destiny and doom’ as a novelist would say, inviting weary sailors to slackness and to sleep.”19

The American technical edge, radar, was ill understood by the senior leadership and ineffectively employed. The Japanese forces, on pins and needles, passed by the radar-equipped Blue around 0143 and surprised the heavy cruisers in the Southern Force when the shutters of their searchlights flicked open. At that same moment, HMAS Canberra shuddered from two torpedoes and the first of 24 shell hits. Her war would be over in less than five minutes. U.S. ships “replied at first only with their antiaircraft batteries and with machine guns. Subsequently a few main battery salvos were fired.” The Japanese, well trained in night surface gunnery, poured a steady stream of shells into the surprised cruisers. The Southern Force was finished as an effective fighting force in less than six minutes as Admiral Mikawa’s forces sighted Vincennes and the Northern Force.20 In less than an hour, Quincy and Vincennes were on the bottom. Astoria, gravely wounded, would succumb hours later. One can imagine a modern day onslaught with anti-ship cruise missiles in the opening engagement.

By August 11th, the American position was critical. The Marines had been able to offload less than half of their supplies. Already exhausted Marines were put on half rations. “The 1st Marine Division was virtually a besieged garrison.”21 Admiral Fletcher’s aircraft carriers had been withdrawn hours after the defeat at Savo Island, much to Marine General Vandegrift’s alarm. None of the Marine defense battalion’s 5-inch coastal defense guns, surface search radars, or fire control radars had made it ashore. Those radars and coastal defense guns, coupled with the Army B-17s in the region, may have helped tip the scales of sea control in the waters north of Guadalcanal at a crucial juncture. Just as Admiral Fletcher’s forces were ordered to protect the landing forces moving ashore, so too the Marines and Army could have assisted the Navy in setting the conditions necessary for their continued survival and success on land.

Geography dictates, according to Tangredi, the need to tailor forces and “that modern counter-anti-access operations need not be the sole province of naval and air forces.”22 Today, the Army, Marines, and Air Force are all investing in maritime warfare systems that can support the Navy. The Army is retooling its Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) for anti-ship missions out to 186-nautical miles.23 The Marines are exploring similar capabilities from their High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS).24 The Air Force recently completed several test firings of the Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM) from B-1B bombers, indicating that they want to play a part in sea control as well.25 Sea control in and around expeditionary advanced bases, which the Marine Corps is reviving, needs to be a joint affair.

In a statement just as relevant today, especially when considering cruise missiles, Admiral Ghormley, commander of the South Pacific Area, foresaw the need for truly joint operations and communicated this to his task forces in the Solomons: “What we wish to achieve is the combination (no matter where the enemy may strike) of our shore-based aircraft and our carrier aircraft against the following targets in order of priority: Carriers, transports, battleships, cruisers, destroyers.”26

The Navy should fully integrate the other services into its Fleet Problems and other exercises to develop the joint capabilities needed for maritime warfare. As Miller notes, despite the hasty tactical planning for Guadalcanal, the Allies “had a broad and well-established base in the doctrines governing landings on hostile shores which had been developed during the years preceding the outbreak of war.”27 We should do the same again, starting by conducting the next Fleet Problem in the Solomons as a joint force on a campaign timescale.

Campaigns Require Sacrifices

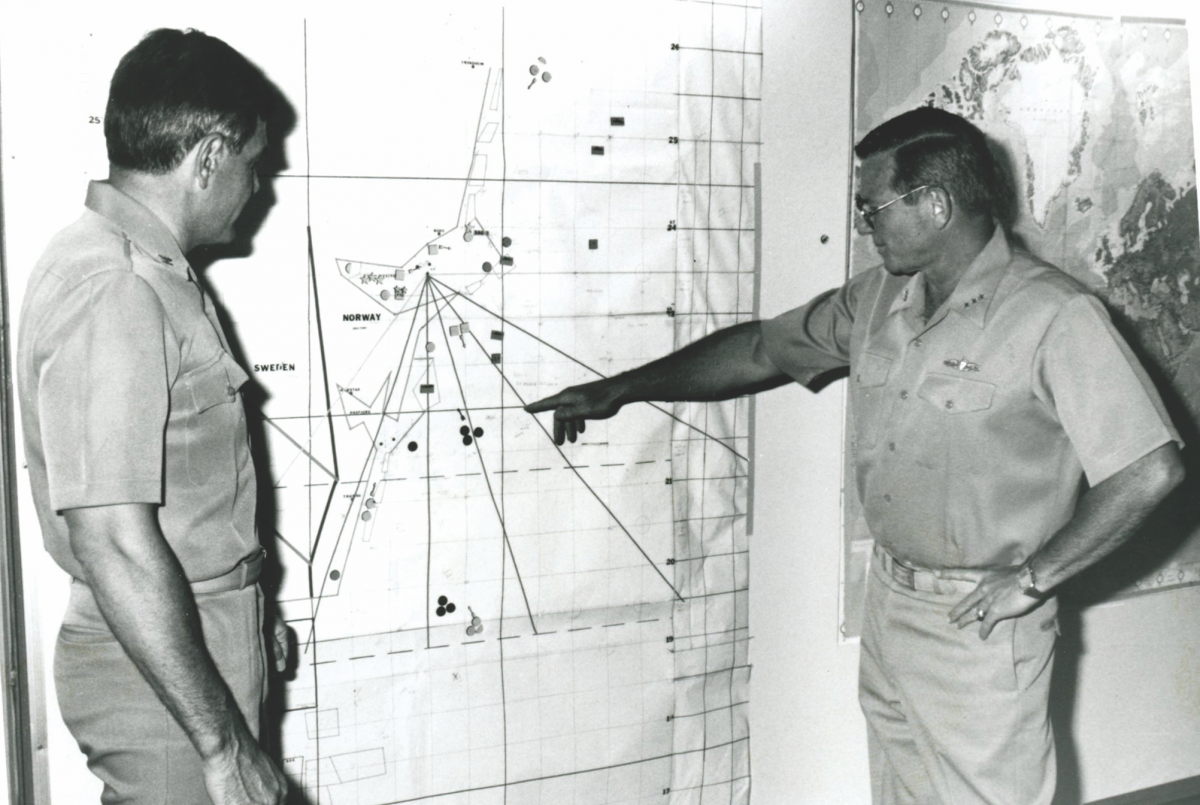

By November 1942, three more major naval battles and countless skirmishes would rack up painful losses for both sides, from aircraft carriers down to destroyers. Each side knew that the final decision for the island, and potentially the war, was drawing near and continued to pour every available asset into the area to sway the outcome. The lessons from those previous battles had been learned, and the new, fiery leadership of Admiral Halsey reinvigorated American forces.

On November 12th, reconnaissance indicated another Tokyo Express run headed to the Solomons to reinforce the Japanese garrison, shell Marine positions, and put Henderson Field out of action—this time with battleships. Admiral Halsey, desperately short on forces but having no other choice, ordered Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan and Rear Admiral Normal Scott to the area in two groups consisting of a few cruisers with a handful of destroyers—a pickup force—against a Japanese force of two battleships, half a dozen cruisers, and a dozen destroyers. Morison remarks that the Japanese force was “obviously too large a bite for Callaghan’s two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and eight destroyers. Yet, with Kinkaid’s carrier-battleship force too far away to help, there was nothing else to be done but for Callaghan to block, and block hard.”28 Captain Cassin Young of the San Francisco remarked to Admiral Callaghan, “[t]his is a suicide mission.” Callaghan replied, “Yes I know, but we have to do it.”29 The Marine position on the shore, and the fate of the campaign, had to be protected at all costs.

Helena first detected the Japanese force at 27,000 yards and immediately sent warnings to Admiral Callaghan in San Francisco. That was the first and last thing to go completely right. San Francisco’s inferior radar left Admiral Callaghan with an incomplete tactical picture, and he was unable to discern whether the returns were his ships or the Japanese. In the ensuing melee, both Admirals Scott and Callaghan and twelve of the thirteen American ships were sunk or damaged. But the desperate action saved Henderson Field from bombardment by two Japanese battleships and kept the airfield in service. Admirals Callaghan and Scott and Lieutenant Commander Bruce McCandless, who assumed command after Admiral Callaghan was killed, would all receive the Medal of Honor for their actions that night.

Non-Linear Effects

The next day, Enterprise, the only remaining carrier in the theater and not fully capable of sustained air operations because of previous battle damage, flew off some of her air wing to operate from Guadalcanal under General Vandegrift.30 Over the next few days, U.S. joint air forces in the region, including the B-17s, would ravage Japanese surface forces. The crew of the battleship Hiei, whose ship was hit more than 85 times the night before and marooned near Savo Island with a jammed rudder, would scuttle their ship on the 13th after a prolonged day of repeated aerial assaults from Marine, Army, and Navy air forces.

On November 14th, Enterprise steamed within range and launched coordinated strikes against Admiral Tanaka’s transport force, which was still steaming south to land reinforcements at Guadalcanal. The Americans launched a combined twelve sorties from Enterprise, Henderson Field, and Espiritu Santo, sinking seven of the eleven transports, with Enterprise pilots flying sorties from both Henderson and the aircraft carrier in the same day—the joint force operated fluidly to achieve a higher sortie rate than Enterprise alone could have generated.31 The remaining transports, though heavily damaged, continued on to Guadalcanal attempting to unload while being constantly harassed and further damaged by Marine fighters and B-17s. Admiral Halsey knew that the carriers could not be readily replaced and thus shepherded the platforms carefully. Air power was the critical capability, but the aircraft and aircrews were expendable. In this three-day battle, Admiral Halsey showed the novel fighting concepts of disaggregating the air wing and how effectively using the joint force in the maritime domain could reduce the risk to irreplaceable forces that needed to defend the objectives on land.

After four months of vicious, close-in fighting on land and sea, the Battle of Tassafaronga on November 30th brought the initial campaign to a close. The United States had penetrated the Japanese barrier and gained a foothold in the region—the anti-access strategy had been broken. A captured Japanese document, reflecting on the campaign, put the case plainly: “It must be said that the success or failure in recapturing Guadalcanal Island, and the vital naval battle related to it, is the fork in the road which leads to victory for them or for us.” President Roosevelt would note, “It would seem that the turning point his this war has at last been reached.”32 Admiral Nimitz and his forces had gained the initiative only through a joint campaign.

Conclusion

As the Navy returns to conducting Fleet Problems and increasing readiness, the lessons from the campaign in the Solomons should be imbued into them.33

Geography reveals cold, hard truths about the ability to sustain a fleet beyond a single engagement. Campaigns at a distance require good stewardship of resources, national level commitment for support, and demands well-founded strategies at the strategic and operational levels to succeed. It drives how battles and wars are fought and won.

Resources will never be as plentiful as you would like. Learn to operate on a “shoestring” budget and still achieve your objectives. It requires tactical and operational level innovation and the freedom to experiment to prevail. Sometimes precious resources—ships and Sailors—must be sacrificed to protect the greater good. Do not forget the desired strategic outcome that put you there in the first place.

The pace of technological advancement and deployment is accelerating, but it cannot be allowed to drown our ability to fight. Officers and Sailors, on ships and shore alike, must embrace and thoroughly understand these technologies, and marry them with well-rehearsed, innovative doctrine to stay ahead of the enemy and prevail.

Maritime campaigns are fundamentally a joint effort at the strategic level. Failing to practice more creatively without joint (or even interagency) partners will harm combat effectiveness as a nation. Well-honed, integrated doctrine and tactics will deliver the non-linear effects in combat capabilities that we need to successfully deter aggression in the Pacific.

Our Navy plies the historic waters off the Solomons now; we need learn to fight there again. Send the joint force there now to figure it out.

Ryan Hilger is a Navy Engineering Duty Officer with the Strategic Systems Program in Washington, DC. His views are his own and do not reflect the opinion of the Department of Defense.

References

[1] Sydney Freedberg, “Generals Worry US May Lose in Start of Next War: Is Multi-Domain the Answer?” Breaking Defense, May 14, 2018, https://breakingdefense.com/2018/05/generals-worry-us-may-lose-in-start-of-next-war-is-multi-domain-the-answer/

[2] Scott Swift. “Fleet Problems Offer Opportunities.” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 144, No. 3, March 2018, https://www.usni.org/print/92920

[3] Scott Swift. “A Fleet Must Be Able to Fight.” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 144, No. 5, May 2018, https://www.usni.org/print/93518

[4] David Wroe, “China eyes Vanuatu military base in plan with global ramifications,” The Sydney Morning Herald, April 9, 2018, https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/china-eyes-vanuatu-military-base-in-plan-with-global-ramifications-20180409-p4z8j9.html

[5] “Duterte: Philippines is separating from US and realigning with China,” The Guardian, October 20, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/20/china-philippines-resume-dialogue-south-china-sea-dispute

[6] Naval Analysis Division, Marshalls-Gilberts-New Britain Party. The Allied Campaign Against Rabaul. United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific), 1946, p. 5.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Michael Hutchens, William Dries, Jason Perdew, Vincent Bryant, and Kerry Moores. “Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons: A New Joint Operational Concept.” Joint Forces Quarterly, Volume 84, 1st Quarter 2017, p. 135.

[9] Samuel Tangredi. Anti-Access Warfare. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2013), p. 13.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Lawrence Freedman. The Future of War: A History. (New York, NY: Public Affairs, 2017), p. 65.

[12] John Miller. Guadalcanal, The First Offensive. (Washington, DC: Department of the Army Historical Division, 1949), p. 4.

[13] The Allied Campaign Against Rabaul, p. 7.

[14] Edward Miller. War Plan Orange. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2007), p. 32-33.

[15] Elmer Potter. Nimitz. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1976), p. 177-179.

[16] Scott Swift, A Fleet Must Be Able to Fight.

[17] Joseph Wylie. “On Maritime Strategy.” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 7, No. 5, May 1953, p. 468.

[18] John Miller, pp. 20-79.

[19] Samuel Eliot Morison. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II: The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942-February 1943. Volume V. (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Co., 1949), p. 32.

[20] Ibid, p. 40.

[21] John Miller, p. 81.

[22] Tangredi, p. 16.

[23] Jeremy Hsu. “The Army Gets back in the Ship-Killing Business.” Wired, March 1, 2017, https://www.wired.com/2017/03/army-converting-missiles-ship-killers-china/

[24] Sydney Freedberg. “Marines Seek Anti-Ship HIMARS: High Cost, Hard Mission.” Breaking Defense, November 14, 2017, https://breakingdefense.com/2017/11/marines-seek-anti-ship-himars-high-cost-hard-mission/

[25] Ben Werner. “Pentagon Tests Next-Gen Anti-Ship Missile from Air Force B-1B Bomber.” USNI News, December 14, 2017, https://news.usni.org/2017/12/14/pentagon-tests-next-gen-anti-ship-missile-air-force-b-1b-bomber

[26] James Steele. “Running Estimate and Summary, 7 December 1941 – 31 August 1942.” War Plans and Files of the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet. American Naval Records Society, 2010. Vol. 1, p. 605.

[27] John Miller, p. 58.

[28] Morison, 235-6.

[29] James Hornfischer. Neptune’s Inferno. New York, NY: Bantam Books, 2012, p. 254.

[30] John Miller, p. 186.

[31] Morison, pp. 264-269.

Naval Analysis Division, Marshalls-Gilberts-New Britain Party. The Campaigns of the Pacific War. United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific), 1946, p. 126.

[32] Morison, p. 287.

[33] Swift, Fleet Problems.

Featured Image: STRAIT OF HORMUZ (Dec. 21, 2018) An MH-60R Sea Hawk helicopter assigned to Helicopter Maritime Strike Squadron (HSM) 71 takes off from the flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS John C. Stennis (CVN 74) during a transit through the Strait of Hormuz, Dec. 21, 2018. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Grant G. Grady/Released) 181221-N-OM854-0135