Read Part 1 on defining distributed maritime operations.

Read Part 2 on anti-ship firepower and U.S. shortfalls.

Read Part 3 on assembling massed fires and modern fleet tactics.

Read Part 4 on weapons depletion and last-ditch salvo dynamics.

Read Part 5 on salvo patterns and maximizing volume of fire.

Read Part 6 on platform advantages and combined arms roles.

Read Part 7 on aircraft carrier roles in distributed warfighting.

By Dmitry Filipoff

Introduction

China’s arsenal of anti-ship weapons is truly a force to be reckoned with, and is superior to that of the United States in many respects. These weapons and the tactics that make use of them can be at the forefront of China’s ability to deny U.S. forces access to the Western Pacific. As both great powers build up and evolve their anti-ship firepower, it is critical to assess their respective schemes of massing fires, and how these schemes may compete and interact in a specific operational context, such as a war sparked by a Taiwan contingency. Whichever side wields the superior combination of tools and methods for massing fires may earn a major advantage in deterrence and in conflict.

China’s Anti-Ship Missile Firepower

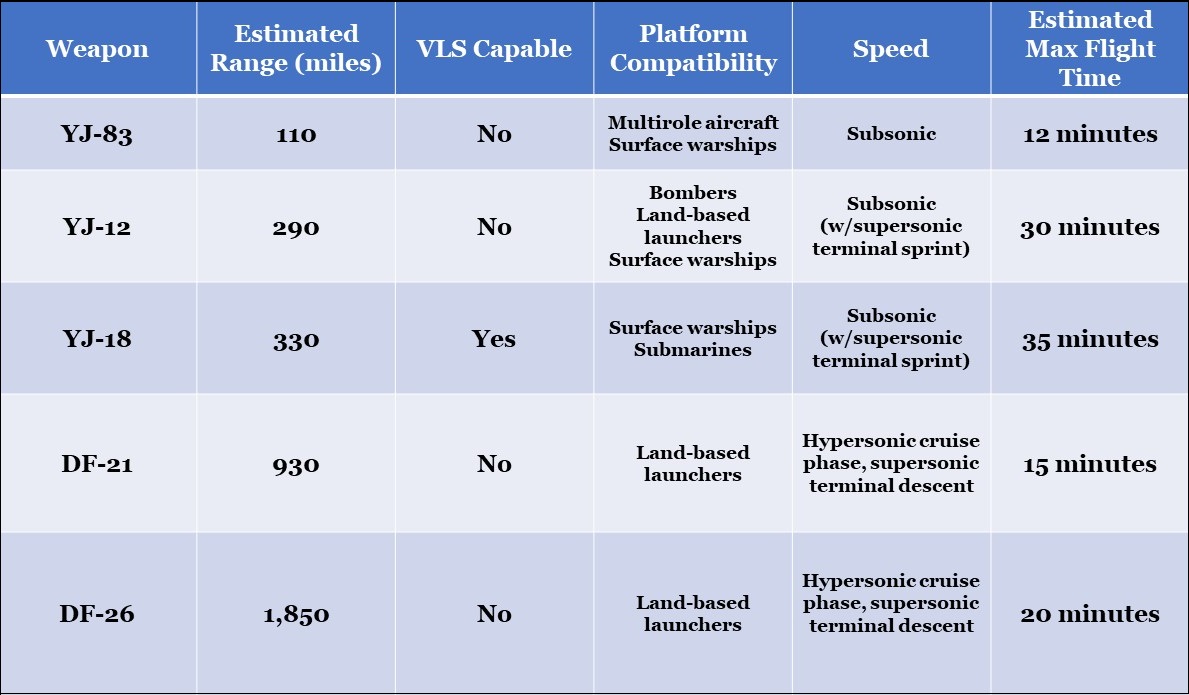

China has assembled a wide array of anti-ship missiles and naval force structure for generating massed fires. These weapons and the way they have been distributed across platform types come together to form an outline for how China can mass fires against warships. These weapons should be assessed through a framework of the specific traits that highlight their mass firing potential, including launch cell compatibility, platform compatibility, range, maximum flight time, numbers of weapons procured, and numbers of weapons fielded per platform.

China’s main anti-ship missiles are the YJ-12, YJ-18, YJ-83, DF-21, and DF-26. The YJ-12 serves as a primary weapon for bombers and coastal launchers; the YJ-18 is a primary weapon for submarines and large surface warships; the YJ-83 is fielded by multirole aircraft and surface warships smaller than destroyers; and the DF-21 and DF-26 ballistic missiles are China’s most long-ranged land-based anti-ship weapons.1 While there are other anti-ship missiles in China’s inventory, those appear relatively uncommon compared to these five weapons.

Each of these weapons, save for perhaps the YJ-83, is relatively modern and introduced into China’s anti-ship arsenal within the past 10-15 years.2 While the recency of introduction suggests the inventory may not be deep enough for a major conflict, China’s precise weapon procurement rates are not as publicly discernible compared to U.S. forces. However, the U.S. Department of Defense has stated that China conducted more than 135 ballistic missile live firings for testing and training in 2021, which “was more than the rest of the world combined,” excluding conflict zones. The DoD made the same remark about 2020, with China firing 250 ballistic missiles that year, and earlier again for 2019, but with no accompanying figure.3 These firing rates suggest that China has invested in a robust missile production industrial base and recognizes the value of building out deep inventories of precision weapons.

The YJ-83 is a relatively common Chinese anti-ship missile that is widely fielded across its surface and air forces. It is similar to the Harpoon in being a smaller, shorter-ranged weapon that is not compatible with vertical launch cells. For warships, it is primarily fielded in box launchers aboard Chinese frigates, corvettes, and small missile boats. Multirole aircraft can field this weapon as well, making it the primary anti-ship missile for non-bomber PLA aircraft, such as land- and carrier-based aviation.4

The lack of launch cell compatibility makes it fielded in relatively low numbers aboard the compatible platforms. The short range and low magazine depth forces the extensive concentration of platforms to mass large enough volumes of fire. The range of the weapon is short enough that aviation can be forced to concentrate in large numbers within or near the limits of modern shipboard air defenses, although attacking aircraft may still have enough space to fire and then dive to spoil semi-active illumination. Like Harpoon, the greater the proportion of YJ-83s in a mass firing sequence, the greater the risk the force will incur.

The YJ-18 strongly stands out in the PLA arsenal for being its only widely fielded anti-ship missile that is compatible with vertical launch cells.5 It is fielded aboard China’s large surface combatants, the Type 52D destroyer and Type 55 cruiser, and a torpedo tube-compatible version of the weapon is fielded aboard PLA submarines.6 By combining a long range of more than 300 miles with launch-cell compatibility, the YJ-18 offers a strong capability for the Chinese surface fleet to distribute across wider areas and still combine large volumes of fire. Primarily because of the YJ-18, it is starkly clear that large U.S. surface warships are heavily outgunned by their Chinese equivalents, and must compensate for the disparity in offensive firepower with superior tactics, defenses, and combined arms methods.

The YJ-12 has similar range to the YJ-18 and is compatible with a larger variety of launch platforms, including coastal launchers and bombers, but crucially it lacks launch cell compatibility.7 The range of China’s bombers and the roughly 300-mile range of the weapon could allow bombers to reach out at long distances, concentrate aircraft well beyond the range of warship air defenses, and fire effectively first. By being compatible with bombers, this weapon can be at the forefront of China’s ability to fire on warships at extreme ranges from the mainland.

The YJ-12 and YJ-18 feature terminal sprint capability, a major force multiplier that is absent from U.S. anti-ship missiles. By accelerating to around Mach 2.5-3.0 after breaking over the horizon view of a warship, these missiles can offer less than half the reaction time for the target warship to react compared to subsonic weapons.8 This allows the missile to cross much more distance from the horizon before the warship can make its first intercept, and reduces the time it takes the missile to get inside the minimum engagement range of major warship defenses. By substantially reducing reaction time, terminal sprint allows lethal effect to be achieved with less volume of fire compared to a slower weapon. These weapons still fly at subsonic speed for most of their flight to maximize range, especially when traveling at sea-skimming altitude. This strengthens the imperative to intercept sea-skimming missiles with aviation well before they can activate their deadly terminal sprint capability against warships.

China’s DF-21D and DF-26 anti-ship ballistic missiles offer critical asymmetric advantages by offering a combination of especially high speed and long range, allowing them to be at the forefront of China’s ability to mass fires against warships. This combination of traits also allows these weapons to combine fires with a large variety of other platforms and payloads on a theater-wide scale. If a Chinese platform is firing anti-ship missiles at a naval formation within the second island chain, the defenders cannot discount the possibility that the salvo could be bolstered by high-end ballistic fires launched from the Chinese mainland. However, if the concentrations of these land-based launch platforms are maintained at their widely separated bases across the mainland, then this will lessen the overlap between their fields of fire and dilute their delivery density. 9

With the anti-ship Tomahawk, the U.S. may soon finally have anti-ship firepower that is more widespread and long-range than what resides within China’s arsenal. But it is a major assumption to think China’s anti-ship capability will remain static in the next 10-15 years as the U.S. builds up its anti-ship Tomahawk inventory. The state of advantage could change if China fields anti-ship weapons similar in design to the Tomahawk, or fields more of its novel missile types, such as the YJ-21 anti-ship missile that was reportedly test fired from a Type 55 cruiser in 2022.10 The YJ-21 could stand to be the first hypersonic, launch-cell compatible, anti-ship missile for Chinese surface forces. While forthcoming variants of the SM-6 could stand to offer similar capability to U.S. forces, it will likely be subject to multiple factors that dilute its anti-ship potential as described in Part 2.11 China has clearly demonstrated a strong interest in developing advanced anti-ship missile capability, and will be motivated to maintain its edge.

Key Elements of China’s Naval Force Structure

China’s force structure features much more variety than the U.S. military in terms of the platform types that can field long-range anti-ship firepower. Select elements and traits of this growing force structure deserve to be highlighted in light of their ability to contribute to mass fires.

Within the past decade China’s surface fleet has emerged as a major force in its own right. After producing multiple short-run variants, several modern warship designs entered serial production, dramatically increasing numbers and capability. Today China’s surface fleet is mainly composed of about eight cruisers, 30 destroyers, 30 frigates, 50 corvettes, and 60 fast-attack missile boats.12 Most of the PLA surface fleet’s capability to fire large volumes of long-range anti-ship missile firepower is concentrated in its large surface combatants, a force of nearly 40 warships that was built within the past ten years. If current production trends hold, this force of large surface combatants could double to around 80 warships within the next decade.13

The asymmetry of certain scenarios and force structure can allow PLA surface warships to take on more favorable missile loadouts compared to the U.S. Navy. Given its expeditionary nature, the U.S. surface fleet faces greater pressures to split its magazine depth across multiple missions, including anti-ship, anti-air, anti-submarine, and land-attack missions. If the Chinese surface fleet is operating within the second island chain, much of the demand for land-attack capability could be offloaded to forces on the Chinese mainland, such as by having bombers, multirole aircraft, and ballistic missiles filling the demand for land-attack strikes. While Chinese frigates and corvettes have virtually no long-range anti-ship or land-attack capability, their anti-submarine capability could alleviate further demand on the larger surface combatants. The U.S. Navy by comparison does not feature frigates or corvettes, which concentrates its surface fleet’s division of labor in its large surface combatants.

By being spared of the need to devote considerable magazine space to land-attack and anti-submarine weapons, China’s large surface combatants could allocate a larger proportion of their magazines to anti-air and anti-ship weapons than equivalent U.S. warships. This advantage could give China’s surface fleet more capability and staying power on a ship-for-ship basis when it comes to fleet-on-fleet salvo combat.

China’s surface forces can be significantly bolstered by non-military elements. China’s coast guard and maritime militia feature numerous vessels, and its commercial shipping fleet is massive. While these ships feature little in the way of firepower, they can considerably enhance the distribution of Chinese forces and complicate targeting by allowing the Chinese surface fleet to mask its presence among these more numerous vessels. China could also reap considerable gains in the ability to mass fires and pose a far more distributed threat if it opts to extensively field containerized launchers that could fire weapons and decoys from commercial ships.14 Missile seekers that are programmed to avoid striking contacts that look like civilian vessels may struggle to differentiate these threats. The threat of hidden arsenal ships residing within China’s massive shipping fleet could pose an especially distributed challenge.

China’s naval service fields bombers within its force structure, unlike the U.S. military. The H-6J variant is optimized for maritime strike and can carry up to six YJ-12 missiles, an increase from the four missiles the H-6G can carry.15 This increased carrying capacity translates into fewer platforms needing to concentrate around a target to mass enough fires.

These bombers are relatively limited compared to their American counterparts with regard to magazine depth. An American B-1B bomber can launch 24 LRASM missiles, a volume of fire that is four times greater than what an H-6J can muster, and with similar weapons range.16 The U.S. can launch a greater volume of fire from its bombers by fielding cruise missiles that are small enough to be compatible with internal rotary launchers, substantially increasing the magazine depth per bomber. By comparison, YJ-12s are large enough weapons that they can only be carried via external hardpoints, limiting the magazine depth of the platform.

However, as mentioned in Part 2, the U.S. Air Force is procuring so few LRASM weapons that long-range anti-ship capability is almost non-existent for the air service.17 The fact that China has dedicated maritime strike bombers within its naval service suggests it is less likely to grossly under-resource their inventory of anti-ship weapons.

The PLAN operates about 50 attack submarines, where all but a few are diesel-electric, which limits their range and endurance compared to nuclear-powered submarines.18 A critical shortfall is the lack of vertical launch cells in all PLAN diesel-electric submarines. They are confined to firing anti-ship missiles from their handful of torpedo tubes, which severely restricts their volume of fire.19 But the ability of these submarines to field anti-ship missiles with terminal sprint capability may allow them to compensate for low volume of fire by launching close-range, high-speed missile attacks against warships.

China fields hundreds of land-based multirole aircraft that could be critical in a naval conflict, including for growing or attriting volumes of fire and securing information advantage.20 Land-based aircraft tend to have longer range than carrier-based aircraft, but most of China’s land-based aircraft are fielded by the PLA Air Force, which will naturally have less familiarity and practice operating over maritime spaces than PLA naval aviation.21 But these aircraft will still likely operate over or near maritime spaces in a Taiwan contingency, making them a considerable factor in naval operations.

Among the many trends of China’s evolving naval force structure, its growing inventory of aircraft carriers stands to substantially tilt the naval balance in critical ways. The U.S. ability to overwhelm China’s naval forces will be enhanced by its expanding arsenal of new anti-ship weapons, but maybe not as much as hoped for because of China’s carriers. A world in which the U.S. military has finally built up enough anti-ship Tomahawks and LRASMs to mass fires against warships is also likely to be a world where China has built around six aircraft carriers, if current production trends hold.22 China is poised to substantially change the balance of naval aviation in the Pacific during the same timeframe it will take the U.S. Navy to field enough weapons to mass anti-ship fires. China’s newfound carrier capability will then be poised to heavily attrit America’s newfound anti-ship capability, which will further drive up the volume of fire the U.S. will have to muster.

But while China may be on track to field more carriers in the Pacific than the U.S. Navy, the U.S. may maintain a critical edge by fielding increasing numbers of the F-35 aboard carriers. It is unclear if China’s carriers will field as many 5th generation aircraft, potentially giving the U.S. major advantages in sensing, networking, and battle management functions that are powerful force multipliers for massing fires.

Nonetheless, the following dueling concepts of operation for mass fires take place in a hypothetical future 10-15 years from now, with both sides fielding considerable carrier aviation capability, and with China able to project a substantial amount of multirole naval aviation over the Philippine Sea.

China versus the U.S. and Competing Schemes of Mass Fires

The U.S. and China have developed forces that assemble massed fires in different ways. In looking at how a potential conflict may play out, it is critical to conceptualize how these different schemes would interact and oppose one another. A comparison of mass firing schemes highlights each nation’s advantages and disadvantages in the context of the other’s capabilities, and forms an outline for how kinetic exchanges could transpire.

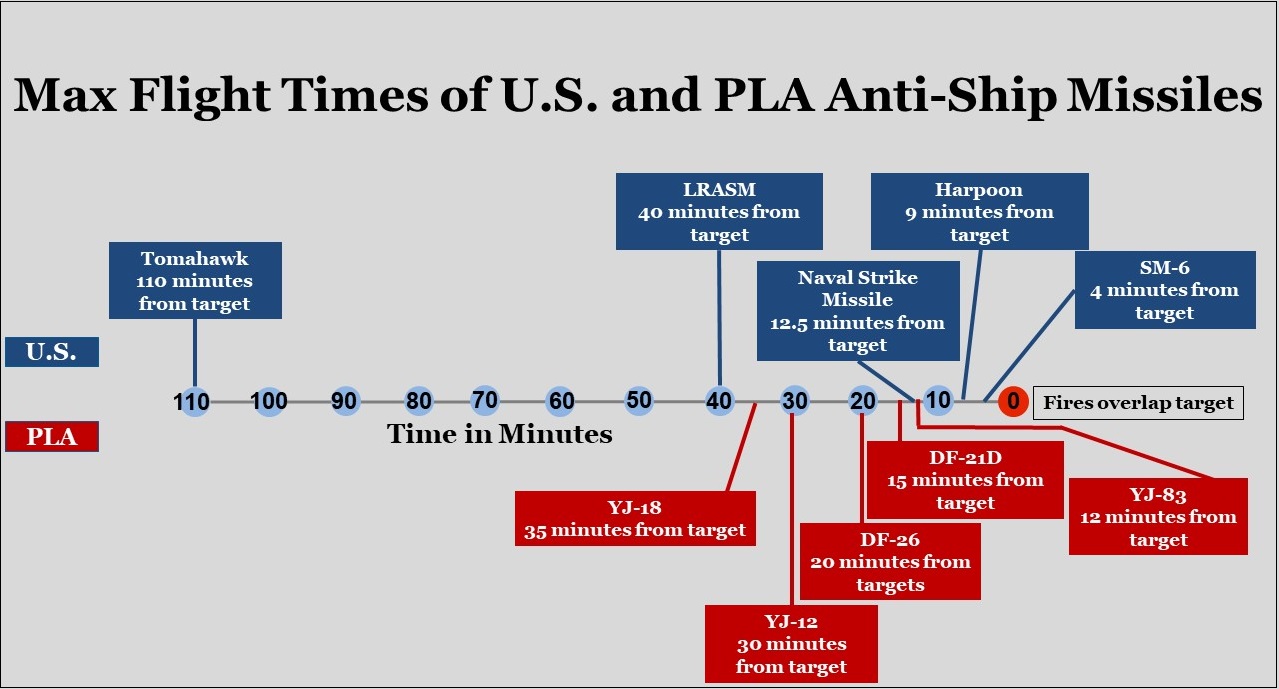

What all of China’s mainstay anti-ship weapons have in common is that they can travel to the limits of their range in roughly 30 minutes. The firing sequences of Chinese massed fires will typically be much shorter and concentrated than that of U.S. forces, such as those that rely heavily on Tomahawks (Figure 1). There will be comparatively less opportunity to counter PLA massed fires after they begin, where a shorter mass firing sequence reduces the defender’s opportunity to reposition defensive airpower to attrit inbound salvos, launch interruptive strikes against waiting archers, and organize last-ditch salvos and their contributing fires. The PLA will benefit from a faster decision cycle compared to forces using much longer firing sequences, where multiple rounds of PLA massed fires could fit into the time it takes to mount a single firing sequence using Tomahawks that are launched near the limits of their range. The emphasis will instead be more about complicating the PLA decision to fire through distribution and other means, carefully pre-positioning airpower to attrit salvos soon after they are launched, and striking PLA archers early enough that they cannot initiate massed fires.

U.S. forces may typically have longer firing sequences by virtue of the Tomahawk’s long range and subsonic speed. However, the longer flight time of the mainstay U.S. anti-ship weapon will give it more opportunity to grow the volume of fire and more ability to leverage waypointing tactics, especially to increase the complexity of threat presentation and to feint attacks in a bid to trigger last-ditch fires. This long range and flight time also translates into more opportunity to maneuver across different salvo patterns, and more ability to recover from deception in pursuit of new contacts. China will be hard pressed to match these advantages, especially when its anti-ship weapons that rival the range of Tomahawk are ballistic missiles that are much more constrained in their ability to maneuver and reorient along their fixed ballistic trajectories.

However, the long range and flight time of Tomahawk gives the defender more opportunity to bring airpower to bear against salvos, and where the range of Tomahawk could outstrip the range of friendly escorting aircraft. Mass firing sequences that heavily depend on Tomahawk will have to strongly emphasize salvo patterns and waypointing tactics to compensate for the weapon’s survivability challenges and to preserve as much volume of fire as possible. These specific challenges and tactics also make Tomahawk especially dependent on naval aviation to provide critical information and air defense support to Tomahawk salvos. If PLA warships manage to get within range of Tomahawk-equipped warships, then many of the advantages that come with Tomahawk’s longer range and flight time will be minimized.

China may hold a critical advantage with respect to interruptive strikes, which are used to disrupt an active firing sequence as it is unfolding. China’s anti-ship ballistic missiles can offer plenty of options for interruptive strikes by virtue of their high speed and long range. Warships that are suspected of being waiting archers in a lengthy firing sequence can be attractive targets for ballistic missile strikes, encouraging those warships to launch earlier and leverage waypointing to artificially increase their time to target. But this comes at the expense of frontloading the firing sequence and reducing the distribution of fires across time. China’s potentially superior ability to launch interruptive strikes could then shift the overall interaction between competing schemes of mass fires. China’s superior interruptive ability can lead to the opponent frontloading their firing sequences, which subsequently affords China more time and opportunity to bring defensive airpower to bear against the incoming salvos, while also giving China more time to organize last-ditch salvos and their contributing fires.

Anti-ship ballistic missiles can cast a shadow over the air defense doctrines of numerous forces operating within the weapons engagement zone, where warships may be forced to split their attention between sea-skimming and ballistic threats simultaneously. Warships deeper in the battlespace may be forced to radiate active sensors for the sake of defending more distant friendly forces from incoming ballistic threats, since being deeper in the battlespace can translate into more opportunity to make midcourse intercepts of those ballistic threats. By being forced to radiate and launch against ballistic threats, these warships could be highlighting their positions to the adversary. But the ability to shoot down ballistic threats will be a critical form of insurance against China’s ability to leverage its potential superiority in interruptive strikes. In this sense, effective ballistic missile defense can interrupt China’s interruptive strikes, and shift the balance of advantage in the ensuing interactions between competing schemes of massed fires.

China’s Multiple Layers of Massed Fires

China’s ability to mass anti-ship fires can be understood in terms of multiple layers. These layers are a function of the range of the weapons and the platforms that field them. Each layer of land-based anti-ship capability adds a new combination of platform types for growing the volume of fire and increasing the complexity of threat presentation. Within these more fixed layers of land-based capability, naval forces can be maneuvered to augment the density of the overlapping fields of fire. While weapons range and platform range are not enough on their own to extrapolate precise concepts of operation, they are an important point of departure for outlining options and limits.

The longest-ranged layer of how China can start to combine anti-ship fires from across land-based platform types is a mix of DF-26 ballistic missiles and bombers. These two delivery systems are China’s most far-reaching options for delivering anti-ship missile firepower, and could come together to threaten naval targets starting at around 1,800 miles from the mainland.23

Massing fires from this limited combination of platforms poses its own set of challenges, especially by having only two main sources of firepower to draw upon. If bombers are destroyed before they can fire, PLA commanders would be forced to compensate by increasing the expenditure of their most high-end anti-ship weapons. Alternatively, if the kill chains enabling the ballistic missiles are undermined or uncertain, the transiting bombers would have virtually no options to increase their volume of fire while in flight, and may be forced to close with targets to secure targeting information for platforms other than themselves.

Bomber sorties could feature large numbers of aircraft to build a greater margin of overmatch to ensure the volume of fire can remain overwhelming in the face of unforeseen challenges and attrition. This was essentially Soviet naval aviation’s doctrine for distant anti-carrier group strikes, where upwards of 70-100 bombers would fly more than a thousand miles from their bases and then heavily concentrate within 250 miles of a carrier battle group to mass fires.24 The need to mass fires at extremely long range confined the Soviet Navy’s options to gambling a major amount of its bomber force structure in each individual carrier attack, while being limited to homogenous force packages to produce mass fires instead of leveraging combined arms tactics. PLA naval aviation is perhaps in the more favorable position of being able to combine bomber fires with ballistic fires at extreme ranges, allowing fewer bombers to be risked per strike, and being able to compensate for bomber attrition in a timely manner with high-speed ballistic weapons.

Even so, China may not want to risk sending unescorted bombers into distant oceans and risk losing these valuable platforms to opposing carrier air wings, where air wings can better optimize themselves for early warning and air defense when reacting to especially long-range attacks.25 Even with the possibility of combining fires with ballistic missiles, the bombers still have to concentrate their platforms inside a 300-mile radius of the target to launch fires. This could present a lucrative and concentrated target for U.S. carrier aircraft, where only a handful of fighters would be enough to credibly threaten a concentration of unescorted bombers. And the fighters can preserve the anti-air threat to bombers even if the bombers drop below the radar horizons of their target warships. Extensive aerial refueling would be required to ensure the bombers have enough aerial escorts that can accompany them on long-range strikes and contend against carrier air. The limitations imposed by refueling copious amounts of smaller escorting aircraft to extreme range could constrain the range of the larger bomber platforms, despite the extensive reach of those aircraft.

While China certainly has some ability to combine fires at the initial 1,800-mile layer, it remains a highly unfavorable scheme for massing fires, especially due to the challenge of providing extreme range aerial escort to bomber forces and a potentially heavy reliance on its most high-end anti-ship weapons.

With the twin overlapping threats of bombers and DF-26s starting at around 1,800 miles from the Chinese mainland, U.S. naval forces can travel another thousand miles closer to China before encountering the next major layer that adds another combination of land-based air and missile forces. These forces include a mix of hundreds of multirole aircraft such as the JH-7, J-10, and J-16 platforms that can field the YJ-83 anti-ship missile.26 The DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missile also comes into range at around 900 miles from the Chinese mainland, assuming the launchers are near the coastline.27

This distance is still beyond the range of unrefueled U.S. carrier air strikes, allowing air wings to focus mainly on defense. But this distance is also roughly where U.S. warships and bombers would first be able to fire on Taiwan and the Chinese mainland with land-attack cruise missiles, creating a strong incentive for the PLA to mount a strong naval and air defense at this distance.

Attacking Chinese multirole aircraft would need to heavily concentrate in large numbers within 100 miles of their targets to mass overwhelming fires with the short-ranged YJ-83. But these aircraft are much better able to defend themselves against carrier aircraft compared to bombers and can diversify their loadouts to include a mix of anti-air and anti-ship weapons. If U.S. aircraft are unable to prevent these PLA aircraft from firing their anti-ship weapons, then the number of aerial targets will drastically multiply after they launch their volume of fire. U.S. aircraft will be forced to divide their attention and anti-air weapons between firing on enemy aircraft and firing on enemy missiles that are roughly ten minutes away from impacting friendly warships. And once PLA aircraft fire their anti-ship missiles, they could be well-positioned to attack the U.S. aircraft attempting to attrit the salvos.

U.S. carrier aircraft can certainly be in a position to inflict similar dilemmas on an adversary with their own anti-ship strikes. But a critical difference is that the aforementioned PLA land-based multirole aircraft have longer range than the U.S. Navy’s F/A-18 aircraft, and airfields can have a higher sortie generation rate than carriers.28 These advantages can give them more opportunity to inflict these dilemmas and with potentially greater numbers on their side.

However, projecting substantial airpower to nearly 800 miles beyond China’s mainland will still create major demands for aerial tanking capability. To make the most of tankers to extend range, this in-flight refueling would have to take place near potentially contested areas, such as the airspace near Taiwan, the Ryukus, and the Batanes island chain. If the airspace around these locales can be effectively contested, China may be severely limited in its ability to project land-based aircraft in large numbers over the Philippine Sea, forcing China’s carriers to be alone in providing multirole airpower beyond the first island chain.

The next major layer of PLA anti-ship firepower begins roughly 300 miles from the mainland. In this layer, coastal YJ-12 batteries and YJ-83s fired from short-range Type 22 missile boats pose an especially distributed form of massing anti-ship fires. These assets can help the PLA project sea denial over much of the East China Sea, the northern areas of the South China Sea, and over the maritime approaches to Taiwan. The fleet of 60 missile boats in particular could be valuable in contesting sections of the Batanes and Ryukyu island chains and the maritime approaches leading toward expeditionary advance bases posted on those islands.29

These three main layers of combined anti-ship capability have more limited dispositions due to being fielded by land-based forces and small surface warships. On top of these more static land-based layers, China’s surface and submarine forces are able to dynamically extend the scope and concentration of China’s ability to mass fires against warships, and provide a maneuvering base of offensive fire. But these forces have their own limits to survivability and their ability to generate large volumes of fire.

Chinese submarines could arguably pose some of the earliest missile threats U.S. forces face by deploying far and away from the Chinese mainland, but their volume of fire is especially constrained due to the lack of vertical launch cells. Chinese submarines could still stalk certain areas such as Yokosuka, where they could fire on depleted warships returning from the fight, divert frontline assets to local submarine hunting patrols, and generate uncertainty around the maritime approaches to critical naval bases. Chinese submarines could also make major contributions to preserving the broader PLA anti-ship missile inventory by making a priority of torpedoing U.S. large surface combatants, which boast large missile magazines and considerable air defense capability.

China’s fleet of large surface combatants, primarily the Type 52D destroyers and Type 55 cruisers, could add significant volume to a mass firing scheme. However, it is debatable how far forward China is willing to employ these ships from the mainland in a high-end conflict. The need for airpower to be on hand to improve survivability for these ships and their salvos, and to provide critical airborne information functions, limits how far these ships can be confidently deployed. If China extends a surface force from beyond the umbrella of airpower’s critical enablers, those surface forces may be alone in contending with hostile salvos and airpower, especially from U.S. carrier air wings. Sending surface warships beyond the range of supporting aviation and into the weapons range of opposing aviation is a recipe for defeat in detail.

The struggle to maintain a substantial amount of multirole aviation out to a thousand miles from the mainland imposes significant liabilities on any mass firing scheme China can assemble at this distance. But until China can confidently field a significant number of its own carrier air wings, the bulk of naval-enabling airpower will have to come from land-based aviation that may be hard-pressed to fight in distant waters. For now, the U.S. may be heavily advantaged in being able to maintain robust combined arms relationships between its surface and carrier air forces regardless of the distance between those forces and land-based airfields. In the near-term, China’s ability to make the most of its surface fleet’s contributions to massed fires will be heavily constrained by the range and sustainability of land-based airpower, and its limited ability to overlay airpower’s critical enablers over distant maritime spaces.

In designing the overall scheme of massed fires with these limitations in mind, China’s surface fleet fits well within the second main layer of China’s anti-ship firepower. By leveraging a combination of YJ-18s launched by ships and YJ-83s launched by multirole aircraft, China can substantially lessen the burden on its bombers and land-based ballistic missiles to mass fires. Instead, it can focus on using much more common platforms and missiles to generate massed fires while posing a more distributed threat.

The similar range of the YJ-12 and the YJ-18 means China’s surface and bomber forces need to concentrate within a similar ring around a target to combine fires. Through combined arms methods, warships could provide critical air defense and sensing support to friendly aircraft and provide a protective screen from which their airpower can leverage. Carrier air wings that pursue bombers and multirole aircraft could be led into Chinese warship air defenses.

The range differential between the the YJ-12, YJ-18, and YJ-83 is small enough to create a disposition where PLA aircraft and warships can readily provide critical enablers to one another, rather than the more divided nature of having U.S. airpower travel far forward to support Tomahawk salvos fired from upwards of a thousand miles away. While the similar ranges of China’s primary anti-ship cruise missiles can certainly increase force concentration, their similar ranges also create a foundation for force-multiplying combined arms relationships and closely integrated force packages.

The second main layer of anti-ship firepower at around 800-1,000 miles from the mainland appears the most preferable to China. But maintaining a robust scheme for massing fires at this distance will not just be a function of the available combinations of capability. For China, it is a critical operational imperative.

Buffering the Pacific: Competing Mass Fires in Operational Context

China’s potential schemes of massed fires have to be assessed in a specific operational context. While there are many dimensions to future contingencies, a core operational challenge for China in a Taiwan contingency is to maintain a maritime buffer zone out to around a thousand miles from the mainland. If U.S. and allied forces can get within this range, they can launch large volumes of land-attack cruise missile fires against China and Taiwan that can considerably complicate PLA operations. If China cannot effectively contest a maritime buffer out to this distance, it would have to devote considerable airpower toward cruise missile defense over oceanic spaces, when that airpower may be sorely needed for operations elsewhere. Preempting the looming threat of hundreds of land-attack cruise missiles launching from U.S. warships and bombers is therefore a critical operational imperative for China. As opposing forces contest sea control, the success of the anti-ship effort will unlock or deny options for follow-on power projection that could have decisive effects on a campaign.

A key question then is what sorts of combined arms relationships can China maintain out to this critical distance from the mainland, what schemes of massed fires those relationships would yield, and how those schemes of massed fires would interact with those of opposing expeditionary forces. The previous section highlighted how at about 800-1,000 miles from the mainland, China’s combined arms relationships for massed fires can consist of bombers, anti-ship ballistic missiles, and land-based aviation. China’s surface and submarine forces can be maneuvered to add to this mix, which considerably increases the potential volume of fire and complexity of threat presentation.

China would be in the challenging position of having to maintain a maritime defense that is forward enough to hold U.S. surface forces at risk before they can launch land-attack fires, but not so far forward that it outstrips the PLA’s ability to add more platform types to its combined arms scheme of massing fires. It also cannot be so far forward that surface forces outstrip their ability to be well-supported by aviation in the critical air defense mission, or else those surface forces could be alone in facing withering anti-ship fires. The need to maintain substantial PLA surface warships near the outer edge of a buffer zone would also limit their maneuver space compared to the opposing expeditionary forces that can leverage the broader expanse of the Philippine Sea and adjacent waters. This asymmetry in maneuver space would simplify the scouting and targeting challenges for expeditionary forces facing warships that are tasked with reinforcing a buffer zone. But these surface warships are critical for providing a major base of fire that can persist at the outer edge of the buffer zone, or otherwise a disproportionately large volume of the available firepower would have to come from more transient platforms such as aircraft.

U.S. forces can impose some of these buffering dilemmas today because the land-attack Tomahawk missile is widely fielded across its surface warships. Those warships would still have to lean very heavily on U.S. submarines and carrier aviation to destroy opposing surface and air forces in advance, where those forces could prevent U.S. warships from reaching firing areas that are within Tomahawk range of Taiwan or China.

The dynamic significantly changes if China’s anti-ship capability remains constant enough that the U.S. can secure a major range advantage with the anti-ship Tomahawk. This range advantage would threaten to split apart the combined arms relationships the PLA is able to maintain in a distant maritime buffer. The anti-ship Tomahawk would force the PLA to depend more on the platforms that are better able to reach out and threaten U.S. warships while circumventing Tomahawk firepower by attacking from different domains. These platforms include aviation, submarines, and ballistic missiles, but each of these has significant disadvantages, such with respect to sustainability, volume of fire, and survivability. This scheme may be the only combined arms mix that could have a chance of attacking distant surface forces before they could fire first against an outranged surface fleet.

A key challenge then is how to maintain a robust mass firing scheme within a forward maritime defense when the defender’s anti-ship capability is heavily outranged. If the defender’s surface force can be more easily fired upon first, then it can threaten to remove a major base of fire that is undergirding the combined arms scheme for much of the maritime buffer.

A surface force that is outranged or at risk of aerial attack must rely on more creative and combined arms tactics to compensate for the inferior ability to fire effectively first. This disadvantage especially requires a force to place heavier emphasis on scouting, counter-scouting, deception, and stealth. By securing distinct advantage in these specific areas, a force can earn vital proximity to an adversary with longer-ranged weapons, or induce them to launch wasteful fires, or complicate their decision to fire at all. Airpower is valuable for executing these specific tactics that help warships compensate for a disadvantage in the ability to fire first, but a distant buffer zone increases these challenges by diluting aviation’s availability while limiting the surface maneuver space.

A force that is more likely to be fired on first may be forced to focus much of its initial strategy on optimizing for defense, so it can absorb enough volume of fire in the hopes of then transitioning to a more offensive posture that has better options against a depleted adversary. But if the adversary is firing with weapons of much longer range, then they can more effectively withdraw from the battlespace without coming under fire themselves. The buffering defenders may have to content themselves with inflicting weapons depletion more so than platform attrition, and maintaining sea denial rather than seizing sea control.

China has unique options for reinforcing a maritime buffer even if its surface forces could one day face major disadvantages in their ability to fire first. By filling the forward edge of the buffer zone with copious amounts of state-owned commercial shipping, China could vastly complicate the sensory picture of the battlespace. China’s surface warships could then lurk among these large commercial vessels, and work with aviation to challenge scouts that attempt to probe and make sense of the morass of maritime contacts. Submarines may struggle to use sonar to isolate warship contacts amidst the heavy churning of many commercial ships. Anti-ship missiles may need to rise above sea-skimming altitudes to dodge commercial ships and discover warship contacts, potentially exposing themselves to more defensive fires and offering more early warning to an adversary. China’s uniquely asymmetric ability to leverage large fleets of state-owned commercial shipping in naval warfare deserves careful consideration, especially within the context of maritime active defense.

While China’s commercial fleets can vastly increase the complexity of its naval threat presentation, the U.S. has its own unique advantages that can provide similar effects. The long reach of the Tomahawk broadens the geography of firing areas enough to where the U.S. can capitalize on alliance advantages. The Tomahawk has long enough range to where it can be fired from within the complex littoral geography of the Japanese and Philippine home islands and into a variety of Indo-Pacific maritime spaces. This could allow U.S. forces to circumvent maritime buffers or fire upon them from their littoral margins, which are mostly allied territories. This concept is somewhat similar to the Cold War-era concept of hiding carriers within Norwegian Fjords to launch strikes against the Soviets.30 Warships traditionally rely on broad oceanic maneuver to be a major enabler, but operating from labyrinthine littoral terrain can also complicate detectability and enhance the complexity of threat presentation even if it comes at the expense of maneuver space.

While operating within fixed geography can certainly help adversaries localize naval forces, it may be more difficult to mass fires against warships residing within these littorals. Operating from these areas substantially increases the opportunity for warships to leverage friendly land-based air defense and aviation for support, increasing the volume of fire required to overwhelm warships. The challenges of navigating over littoral terrain can also force missile salvos to engage in tactically unfavorable behavior. Anti-ship missiles may have to depart from sea-skimming altitudes when flying over land, or burn more range to maintain themselves over water at low altitudes while taking more circuitous routes toward littoral contacts. Although it may increase warship findability in some respects, littoral firing areas could improve defensibility enough to compensate. The U.S. can carefully consider how the Maritime Strike Tomahawk opens up vast opportunity for launching massed fires against opposing fleets from friendly littorals.

Figure 2 highlights how these competing fields of fire overlap, and how firing areas located within these island littorals offer key advantages. These littorals can help U.S. forces circumvent a PLA buffer zone and bring those forces within Tomahawk range of Taiwan and the mainland coast. These separate areas also offer a substantial degree of overlap for combining fires over key geography. Tomahawk-equipped forces lurking within the complex littorals of Kyushu and the central Philippines will be able to combine and mass fires with one another over Taiwan and a substantial area of the Philippine Sea.

These dueling schemes of massed fires therefore look to increase their complexity of threat presentation with unconventional means. China’s navy could aim to preserve its maritime buffer by lurking within a vast array of commercial vessels, and the U.S. Navy may seek to circumvent or damage the buffer from within a web of allied island geography. While this hardly makes for a traditional view of maneuvering battle fleets exchanging heavy fire, modern navies may be driven toward such methods by the unforgiving ferocity of naval salvo combat and its overriding insistence on firing effectively first.

Conclusion

China’s ability to mass fires against warships is a product of a truly historic evolution. China was a third-rate maritime power only two decades ago, but it has transformed into a force that heavily outguns the U.S. Navy in major respects. China has clearly stolen a march on the U.S. when it comes to developing advanced anti-ship firepower, and now the U.S. is racing to close the gap. But it will still be many years before the U.S. has the tools in place to have decent options for massing fires. By then, the Chinese naval arsenal may have become something even more fearsome.

Part 9 will focus on the force structure implications of DMO and massed fires.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content and Community Manager of its naval professional society, the Flotilla. He is the author of the “How the Fleet Forgot to Fight” series and coauthor of “Learning to Win: Using Operational Innovation to Regain the Advantage at Sea against China.” Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. For PLA anti-ship cruise missile capabilities and platform compatibility, see:

Dr. Sam Goldsmith, “VAMPIRE VAMPIRE VAMPIRE The PLA’s anti-ship cruise missile threat to Australian and allied naval operations,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, pg. 10, April 2022, https://ad-aspi.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/2022-04/Vampire%20Vampire%20Vampire_0.pdf?VersionId=tHAbNzJSXJHskd9VppGNRcTFC4hW7UqD.

For ballistic missile capabilities, see:

“Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 64-67, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF/.

2. For Y-18 and DF-26 introduction timeframes, see:

Michael Pilger, “China’s New YJ-18 Antiship Cruise Missile: Capabilities and Implications for U.S. Forces in the Western Pacific,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, October 28, 2015, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/China%E2%80%99s%20New%20YJ-18%20Antiship%20Cruise%20Missile.pdf.

For YJ-83, YJ-12, and YJ-18 introduction timeframes, see:

Dennis M. Gormley, Andrew S. Erickson, and Jingdong Yuan, “A Potent Vector: Assessing Chinese Cruise Missile Developments,” Joint Force Quarterly 75, September 30, 2014, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/577568/a-potent-vector-assessing-chinese-cruise-missile-developments/.

For DF-21D introduction timeframe, see:

Andrew S. Erickson, “Chinese Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile Development and Counter-intervention Efforts,” Testimony before Hearing on China’s Advanced Weapons Panel I: China’s Hypersonic and Maneuverable Re-Entry Vehicle Programs U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, February 23, 2017, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Erickson_Testimony.pdf.

3. For assessments of PLA ballistic missile firing rates across China Military Power Report editions, see:

“Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 64, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

“Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 60, 2021, https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/03/2002885874/-1/-1/0/2021-CMPR-FINAL.PDF.

“Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 55, 2020, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Sep/01/2002488689/-1/-1/1/2020-DOD-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT-FINAL.PDF.

4. For YJ-83 capabilities, see:

Dr. Sam Goldsmith, “VAMPIRE VAMPIRE VAMPIRE The PLA’s anti-ship cruise missile threat to Australian and allied naval operations,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, pg. 10, 13, 16, 20, April 2022, https://ad-aspi.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/2022-04/Vampire%20Vampire%20Vampire_0.pdf?VersionId=tHAbNzJSXJHskd9VppGNRcTFC4hW7UqD.

5. Michael Pilger, “China’s New YJ-18 Antiship Cruise Missile: Capabilities and Implications for U.S. Forces in the Western Pacific,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, October 28, 2015, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/China%E2%80%99s%20New%20YJ-18%20Antiship%20Cruise%20Missile.pdf.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. For terminal sprint capability, see:

Michael Pilger, “China’s New YJ-18 Antiship Cruise Missile: Capabilities and Implications for U.S. Forces in the Western Pacific,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, pg. 2, October 28, 2015, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/China%E2%80%99s%20New%20YJ-18%20Antiship%20Cruise%20Missile.pdf.

9. Gerry Doyle and Blake Herzinger, Carrier Killer: China’s Anti-Ship Ballistic Missiles and Theater of Operations in the early 21st Century, Helion & Company, pg. 49, 2022.

10. Amber Wang, “Chinese military announces YJ-21 missile abilities in social media post read as warning to US amid tension in Taiwan Strait,” South China Morning Post, February 2, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3208763/chinese-military-announces-yj-21-missile-performance-social-media-post-read-warning-us-amid-tension.

11. “U.S. Hypersonic Weapons and Alternatives,” Congressional Budget Office, pg. 45, January 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-01/58255-hypersonic.pdf.

12. For Chinese surface fleet ship types and numbers, see:

“Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 53-54, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

Ronald O’Rourke, “China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, pg. 8, 27-33, December 1, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33153/265.

Tayfun Ozberk, “China Launches Two More Type 052DL Destroyers In Dalian,” Naval News, March 12, 2023, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2023/03/china-launches-two-more-type-052dl-destroyers-in-dalian/.

13. Based on the aforementioned sources listed in reference #12, China built roughly 30 destroyers and eight cruisers in a ten-year period from 2012-2022.

14. Ronald O’Rourke, “China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, pg. 13-14, December 1, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33153/265.

15. “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 60, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

16. Oriana Pawlyk, “B-1 Crews Prep for Anti-Surface Warfare in Latest LRASM Tests,” Military Times, January 3, 2018, https://www.military.com/dodbuzz/2018/01/03/b-1-crews-prep-anti-surface-warfare-latest-lrasm-tests.html.

17. “Department of Defense Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 Budget Estimates,” Navy Justification Book Volume 1 of 1 Weapons Procurement, Navy, Page 1 of 10 P-1 Line #16, (PDF pg. 261), April 2022, https://www.secnav.navy.mil/fmc/fmb/Documents/23pres/WPN_Book.pdf.

18. Ronald O’Rourke, “China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, pg. 8, December 1, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33153/265.

19. Captain Christopher P. Carlson, “Essay: Inside the Design of China’s Yuan-class Submarine,” USNI News, August 31, 2015, https://news.usni.org/2015/08/31/essay-inside-the-design-of-chinas-yuan-class-submarine.

20. The Military Balance 2022: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defense Economics, The International Institute of Strategic Studies, Routledge, pg. 259-261, February 2022, https://www.iwp.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/The-Military-Balance-2022.pdf.

21. Ian Burns McCaslin and Andrew S. Erickson, “Selling a Maritime Air Force The PLAAF’s Campaign for a Bigger Maritime Role,” China Aerospace Studies Institute, pg. 15-16, April 2019, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Research/PLAAF/2019-04-01%20Selling%20a%20Maritime%20Air%20Force.pdf.

22. For PLA carrier production rates, see: “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 55, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

23. For DF-26 range, see:

“Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 64, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

For H-6J bomber range, see:

“Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 60, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

24. Maksim Y. Tokarov, “Kamikazes: The Soviet Legacy,” U.S. Naval War College Review, Volume 1, 67, 2014, pg. 13, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1247&context=nwc-review.

25. Lieutenant Commander James A. Winnefeld, Jr., “Winning the Outer Air Battle,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, August 1989, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1989/august/winning-outer-air-battle.

26. For JH-7 YJ-83 compatibility, see:

Dr. Sam Goldsmith, “VAMPIRE VAMPIRE VAMPIRE The PLA’s anti-ship cruise missile threat to Australian and allied naval operations,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, pg. 13, April 2022, https://ad-aspi.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/2022-04/Vampire%20Vampire%20Vampire_0.pdf?VersionId=tHAbNzJSXJHskd9VppGNRcTFC4hW7UqD.

For J-16 compatibility, see:

Andreas Rupprecht, “Images show PLAAF J-16 armed with YJ-83K anti-ship missile,” Janes, February 18, 2020, https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/images-show-plaaf-j-16-armed-with-yj-83k-anti-ship-missile.

For J-10 compatibly, see: “New Cruise Missile Confirmed For China’s J-10C Fighter: An Anti-Ship Weapon to Boost Export Prospects?” Military Watch Magazine, March 4, 2022, https://militarywatchmagazine.com/article/new-cruise-missile-confirmed-for-china-s-j-10c-fighter-an-anti-ship-weapon-to-boost-export-prospects.

27. For DF-21 range, see:

“Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 64, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

28. Air bases can employ “elephant walks” where large numbers of aircraft are surged from an airfield in a back-to-back manner that is not feasible for carriers. Damaged airbase runways are also generally easier to repair than damaged carrier flight decks, such as by using fast-drying concrete that can be ready in several days.

For considerations for air base sortie generation, see:

Christopher J. Bowie, “The Anti-Access Threat and Theater Air Bases,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2002, https://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/2002.09.24-Anti-Access-Threat-Theater-Air-Bases.pdf.

For carrier sortie generation rates, see:

“CVN 78 Gerald R. Ford Class Nuclear Aircraft Carrier (CVN 78),” December 2021 Selected Acquisition Report (SAR), pg. 4, April 28, 2022, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/FOID/Reading%20Room/Selected_Acquisition_Reports/FY_2021_SARS/22-F-0762_CVN_78_SAR_2021.pdf.

“Appendix D: Aircraft Sortie Count,” (for Operational Desert Storm), https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/u/us-navy-in-desert-shield-desert-storm/appendix-d-aircraft-sortie-count.html.

29. Ronald O’Rourke, “China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, pg. 40, August 1, 2018, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33153/222.

30. “Vice Admiral Hank Mustin on New Warfighting Tactics and Taking the Maritime Strategy to Sea,” Center for International Maritime Security, April 29, 2021, https://cimsec.org/vice-admiral-hank-mustin-on-new-warfighting-tactics-and-taking-the-maritime-strategy-to-sea/.

Featured Image: The Type 55 guided-missile destroyer Nanchang (Hull 101) attached to a naval vessel training center under the PLA Northern Theater Command steams in tactical formation to occupy attack positions in an undisclosed sea area during a recent 10-day maritime training exercise. (eng.chinamil.com.cn/Photo by Zou Xiangmin)