By Wilder Alejandro Sanchez

Written by Wilder Alejandro Sanchez, The Southern Tide addresses maritime security issues throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. The column discusses regional navies’ challenges, including limited defense budgets, inter-state tensions, and transnational crimes. It also examines how these challenges influence current and future defense strategies, platform acquisitions, and relations with global powers.

Unmanned surface vessels (USVs) are sailing full steam ahead, as evidenced by their (deadly) efficiency in attacks by the Ukrainian armed forces against Russian targets across the Black Sea. Though the security landscape in Europe is dramatically different from that of the Western Hemisphere, new technologies are always of interest to any armed service and USVs should be no exception. Whether USVs have a future in Latin America and the Caribbean merits deeper exploration.

Recent Developments

It is beyond the scope of this commentary to list or analyze all USV developments, but it is important to note that new platforms continue to be built and utilized worldwide. In the Black Sea, Ukraine has continued to use its deadly Sea Baby USVs. Several governments and industries want to develop USVs to add to their fleets. In the United States, the Navy’s “newest Overlord Unmanned Surface Vessel Vanguard (OUSV3), was recently launched from Austal USA’s shipyard in Mobile, Alabama,” the service reported in January. Also, the Louisiana-based shipyard Metal Shark is developing the USV Prowler and the micro USV Frenzy. As for future platforms, in Europe, the Netherlands announced its first domestic design for a USV to be used by the Dutch Navy. And in Asia, Korea’s Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI) and the US software company Palantir Technologies signed a Memorandum of Understanding on 14 April to also co-develop a USV. USV development is flourishing around the globe.

In the Western Hemisphere, US Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) has become a testing ground for USV technology. In late 2023, ten Saildrone Voyager USVs were launched from Naval Air Station Key West’s Mole Pier and Truman Harbor to help improve domain awareness during US Fourth Fleet’s Operation Windward Stack. According to SOUTHCOM, “Windward Stack is part of 4th Fleet’s unmanned integration campaign, which provides the Navy a region to experiment with and operate unmanned systems in a permissive environment … all designed to move the Navy to the hybrid fleet.” The command aims to use its Area of Responsibility (AOR) as an innovation hub for the US military, partners and allies, and the defense industry.

Regarding the late-2023 test, SOUTHCOM’s 2024 Posture Statement explains, “U.S. Naval Forces Southern Command/U.S. Fourth Fleet held its Hybrid Fleet Campaign Event, hosting 47 Department of Defense Commands, 10 foreign partners, and 18 industry partners to foster innovation and experimentation to inform the Unmanned Campaign and Hybrid Fleet.” This experimentation has included advanced kill chains, contested operations, survivability, and sustainment at sea.

Under General Laura Richardson’s command, SOUTHCOM aims to “integrate tomorrow’s technology into our operations and exercises today” by investing in robotics, cyber technology, artificial intelligence, and machine learning to “overmatch our adversaries and assist the region’s democracies.” Expanding SOUTHCOM’s missions to include testing new technologies, including USVs, is another tactic to expand the command’s importance within the US military.

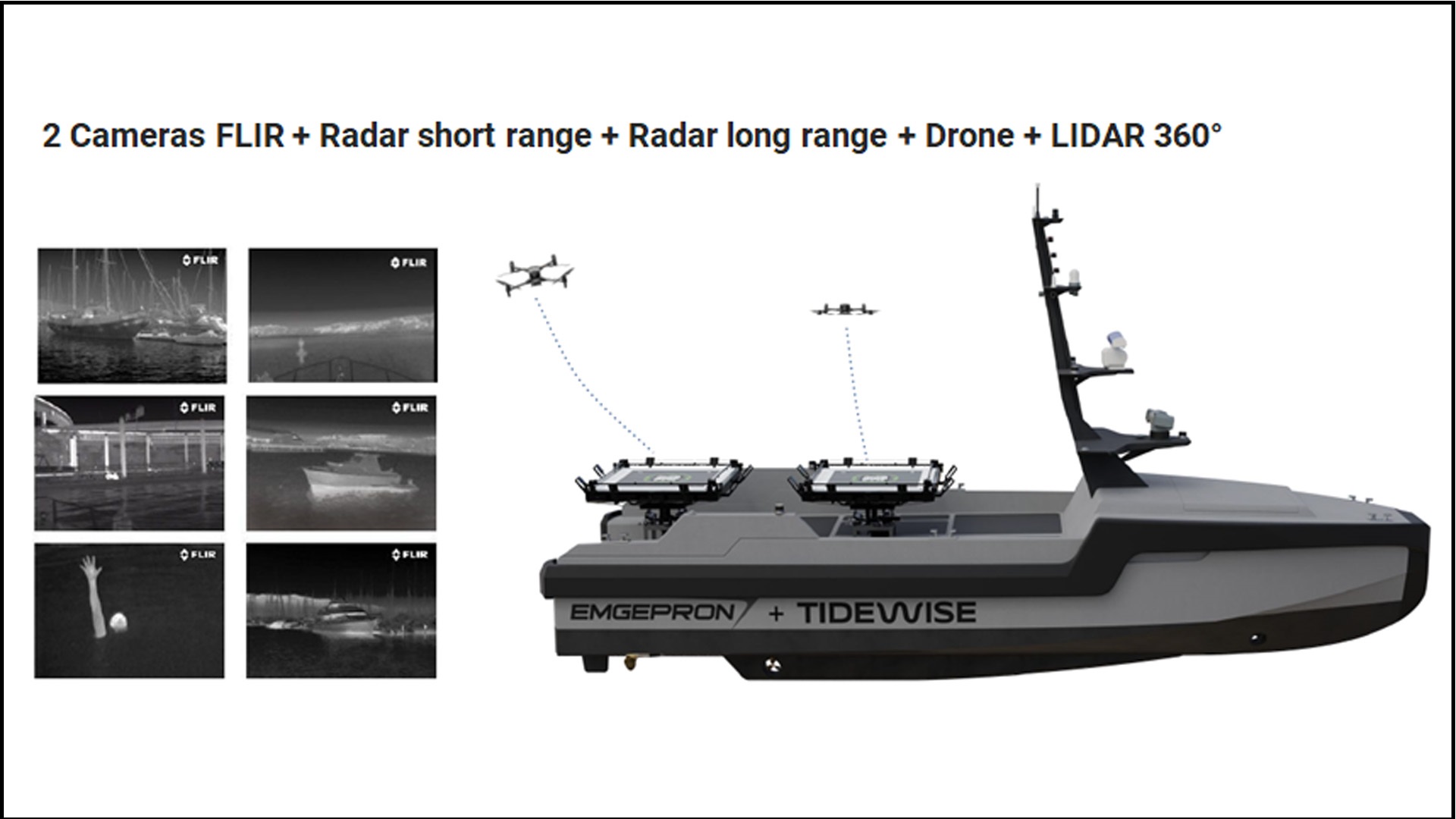

Latin American-made USVs are also on the horizon. In early 2024, the Brazilian shipyard Emgepron announced a partnership with the local start-up Tidewise to manufacture the USV Suppressor. A company press release states that the Suppressor is the first platform developed in the Brazilian or Latin American defense market. Two variants of the Suppressor will be built: the seven-meter Suppress or seven and the 11-meter Suppressor 11. While regional navies have robots for underwater operations like search and rescue, USVs are not yet operated across the region.

Do USVs have a future in Latin America and the Caribbean?

While the possibility of inter-state warfare across Latin America and the Caribbean is minimal (Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro’s belligerent statements notwithstanding), there are several non-combat maritime missions in which USVs could be helpful. Dr. Andrea Resende, professor at Brazil’s University of Belo Horizonte (Centro Universitário de Belo Horizonte: UNIBH) and Una Betim University (Centro Universitário Una Betim: UNA), and Christian Ehrlich, director of the Institute for Strategy and Defense Research and a recent graduate from Coventry University with a focus on maritime security, have both made this argument.

Dr. Resende notes that USVs could be used by the Brazilian Navy and other regional navies as intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) vehicles to locate suspicious vessels. For example, USVs could locate vessels engaged in the trafficking of illicit narcotics, the famous narco-boats or narco-subs. Moreover, USVs could locate illegal, unreported, or unregulated (IUU) fishing vessels. There is a tendency to think that distant water fishing fleets (DFW) are the primary perpetrators of IUU fishing in the Western Hemisphere, particularly from China. But, in reality, DWF fleets primarily operate in the South Atlantic and South Pacific, while local artisanal fishing vessels work illegally across Latin America and the Caribbean. USVs would help locate smaller IUU fishing vessels, which are more challenging to locate than a vast fleet of hundreds of ships.

In other words, USVs offer over-the-horizon capabilities for regional navies and coast guards to locate different types of vessels. Imagine an offshore patrol vessel (OPV) deploying a helicopter, a rigid inflatable boat, and a USV; quickly becoming a small fleet with vast surveillance and interception capabilities.

Moreover, USVs have practical applications for other non-combat and non-security operations, like search and rescue missions and scientific operations. Ehrlich noted that USVs can also be helpful for offshore infrastructure, “particularly to protect offshore oil platforms.” The platforms can also be used for near-shore operations, like port security.

POV video captured by Saildrone Explorer SD 1045’s onboard camera showing large waves and heavy weather conditions inside Hurricane Sam in the Atlantic Ocean at 1414UTC, Sept 30, 2021.

USVs vs UAVs and UGVs

Will USVs eventually be a component of Latin American and Caribbean fleets? The short answer is yes, but when exactly this will occur is debatable as acquisition programs vary depending on each service and, unsurprisingly, budgetary issues.

A parallel can be made with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), which have become quite popular with regional militaries. Virtually every service across the region operates UAVs. In May alone, the United States donated six Aerovironment UAV systems to El Salvador’s military for border patrol operations. Meanwhile, the Brazilian UAV company Xmobots announced the training of 21 Brazilian Army personnel to operate the company’s Nauru 100C UAV. There is a clear proliferation of UAVs across Latin America and the Caribbean.

On the other hand, as this analyst wrote in Breaking Defense, unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) have not found much interest in Latin America. The Brazilian Army is reportedly interested in European-made UGVs; however, UGVs have yet to become popular among Latin American armies compared to the United States, Europe, and elsewhere.

Will USVs become the next UAV or the next UGV? So far, there are not enough data points for a proper prediction. Emgepron’s Suppressor project suggests that at least one company is willing to test the water, so to speak, to see if there is regional interest. If successful, Emgepron could quickly corner the Brazilian defense market with its homegrown USV.

In his comments to CIMSEC, Ehrlich brought up an important issue: long-term vision. For the maritime security expert, “the culture of regional navies” is the major obstacle to acquiring (or attempting to develop locally) USVs. Regional ministries of defense and navies continue to be focused on “operating traditional systems due to a doctrine that does not foment innovation.” Ehrlich mentioned that only the Brazilian Navy is interested in acquiring or developing USVs, including for potential combat missions.

Meanwhile, Dr. Resende explained that a critical factor is the budget of regional armed forces, which tend to suffer “cyclical crises” for various reasons. “Hence, the budgets for investing in the acquisition and training to utilize USVs may be limited.” Moreover, for Dr. Resende, the future of USV technology is part of a broader discussion of the present and future missions of armed forces since they face “greater restrictions as compared to the armed forces in the Global North.”

Ehrlich’s comments about vision and institutional ambition to develop new capacities are a useful lens for gauging these developments. Unsurprisingly, a Brazilian company, Emgepron, is the first in the region to attempt to develop a USV, given the Brazilian Navy’s strong interest in developing the defense industry. Several other South American shipyards are engaged in ambitious projects, including constructing frigates, offshore patrol vessels, transport vessels, and even an icebreaker; however, the Brazilian defense industry still leads the way. Perhaps if the Brazilian Navy positively reviews the Suppressor USV, other regional navies may also be interested in acquiring it.

Finally, there are obvious physical and technical requirements for a ship to transport and operate a USV, which means some basic adaptations will be needed for any ship to utilize this new technology. Navies with older vessels or a surface fleet composed of small vessels will be less likely to acquire USVs, though they could be utilized for port security and other near-shore operations, so they do not have to voyage far from a naval base.

As the war in Ukraine continues, a revolution regarding military technology is underway, and the word “Unmanned” has become very popular. Latin American and Caribbean militaries have quickly adopted UAV technology; however, UGVs have yet to be widely utilized. Likewise, regional naval forces have yet to show major interest in unmanned surface vessels beyond Brazil, and budgetary, doctrinal & technical issues are still obstacles to greater adoption. While USVs could help Latin American and Caribbean naval forces achieve their missions, not all services are in a position to acquire them. More research is necessary to understand which navies, and ministries of defense, have the long-term vision and interest in this technology. In Latin America and the Caribbean, USVs are on the horizon, but they are not yet ready to dock.

Wilder Alejandro Sánchez is an analyst who focuses on international defense, security, and geopolitical issues across the Western Hemisphere, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe. He is the President of Second Floor Strategies, a consulting firm in Washington, DC, and a non-resident Senior Associate at the Americas Program, Center for Strategic and International Studies. Follow him on X/Twitter: @W_Alex_Sanchez.

Featured Image: RNMB Harrier USV. (Royal Navy photo)