On August 18th South Korea selected Boeing’s F-15SE Silent Eagle as the sole candidate for Phase III of its Fighter eXperimental Project (F-X) over Lockheed Martin’s F-35A and the Eurofighter Typhoon. The decision has drawn vociferous criticism from defense experts who fear the selection of F-15SE may not provide the South Korean military with the sufficient Required Operational Capabilities (ROCs) to counterbalance Japan and China’s acquisition of 5th generation stealth fighters.

In hindsight, Zachary Keck of The Diplomat believes that Republic of Korea’s (ROK)preference for the F-15SE over two other competitors was “unsurprising.” After all, Boeing won the previous two fighter competitions with its F-15-K jet. In 2002 and 2008, South Korea bought a total of 61 F-15K jets from Boeing. South Korea’s predilection for the F-15SE is understandable given its 85% platform compatibility with the existing F-15Ks.

- The ROK Air Force has 60 F-15K Slam Eagles in service with its 11th Fighter Wing based in Taegu.

However, the most convincing explanation seems to be the fear of “structural disarmament” of the ROK Air Force should it choose to buy yet another batch of expensive fighters to replace the aging F-4 Phantom and F-5 Tiger fighters. Simply stated, the more advanced the fighter jet, the more costly it is. The more expensive the jet, the fewer the South Korean military can purchase. The fewer stealth fighters purchased, the smaller the ROK Air Force.

Indeed, the limitations of South Korea’s US$7.43 billion budget for fighter acquisition and procurement (A & P) seems to have been the primary motivating factor in selecting the F-15SE. As Soon-ho Lee warned last month, “if the F-X project is pursued as planned, the ROK Air Force may have to scrap the contentious Korean Fighter eXperimental (KFX) project, which [may leave] the ROK Air Force [with] only around 200 fighters.”

The F-15SE enjoyed an undeniable price advantage in competition with the F-35A. Though the F-15SE does not actually exist yet, the New Pacific Institute estimates by looking at previous F-15 K sticker pricesthat a sixty plane order would cost $6 billion. The latest estimates from the Pentagon and Lockheed Martin put the unit cost of an F-35A at approximately $100 million, plus $16 million for the engine. Under this new price target (which may prove optimistic), 60 F-35As could cost the ROK over $7 billion.

But now that the decision has been made, how will the purchase of the F-15SE affect the ROK military’s operational and strategic capabilities?

The acquisition of the F-15SE would have little to no impact on South Korea’s current air superiority over the North. The gap in air power is simply too wide. As James Hardy of IHS Jane’s Defence Weekly wrote last year, “Estimates by IHS Jane’s reckon that North Koreahas only 35 or so MiG-29 ‘Fulcrum’ air-supremacy fighters in service, alongside about 260 obsolete MiG-21 ‘Fishbeds’ and MiG-19 ‘Farmers.’” This may explain Jae Jung Suh’s of John Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies claim that “quantitative advantage quickly fades when one takes account of the qualitative disadvantages of operating its 1950s-vintage weapons systems.”

That said, as I noted in my previous article, the factors fueling the arms race among the major East Asian powers are two-fold: the ongoing territorial rows over disputed islands and seas, and the fear of their rival’s future capabilities. These two factors account for the fact that defense budget increases and acquisition of improved capabilities by China, Japan, and South Korea were reactions to perceived threats posed by their rivals’ attempts to rearm themselves.

This helps to explain why many South Korean defense analysts and ROK Air Force officers are outraged by the Park Geun-hye Administration’s decision to stick with plans to purchase the F-15SE. In a recent telephone interview, a friend of mine of who is a retired ROK Air Force major told me that the ROK’s purchase of F-15SE is akin to “buying premium DOS Operating System instead of purchasing Windows 8.” In other words, some ROK defense analysts and many of its Air Force officers believe that the F-15 series is obsolescent and does not measure up to Japan’s planned purchase of the F-35 or China’s indigenous production of the J-20.

But in order to achieve regional strategic parity with its powerful neighbors, South Korea must spend at least 90% of what its rivals spend on their national defense. The ROK’s $31.8 billion defense budget pales in comparison to China’s $166 billion. And it is still substantially smaller than Japan’s $46.4 billion. Exacerbating this problem is the current administration’s reluctance to increase the ROK defense budget in the face of decreasing tax revenues and soaring welfare expenditure.

No matter which stealth fighter the ROK chooses, the ROK’s defense budget is inadequate to achieve strategic and tactical air parity with its rivals or tip the regional balance of power in its favor.

Despite the fiscal constraints imposed by the Park Geun-hye Administration, there are alternative solutions the ROK can consider to meet its strategic needs.

One option would be to delay purchasing a new aircraft. This option would give Lockheed Martin time to enter mass production of the aircraft, at which time it might be able to offer a more affordable price. Lockheed has pledged to “work with the U.S. government on its offer of the F-35 fighter for [the ROK].” But if that offer does not translate into cheaper unit costs, it is meaningless. Even if Seoul agrees to buy the F-35, the structural disarmament that could result combined with budget shortfalls could cripple the ROK Air Force’s operational readiness.

Another option would be to reduce the size and budget of the ROK Army to accommodate the purchase of either the F-35 or the Eurofighter. But since the ROK Armed Forces remains Army-centric given the military threat from North Korea, this seems unlikely. As Michael Raska of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies has written, “the composition, force structure and deployment of the ROK military have each remained relatively unchanged” and will remain so in the years to come.

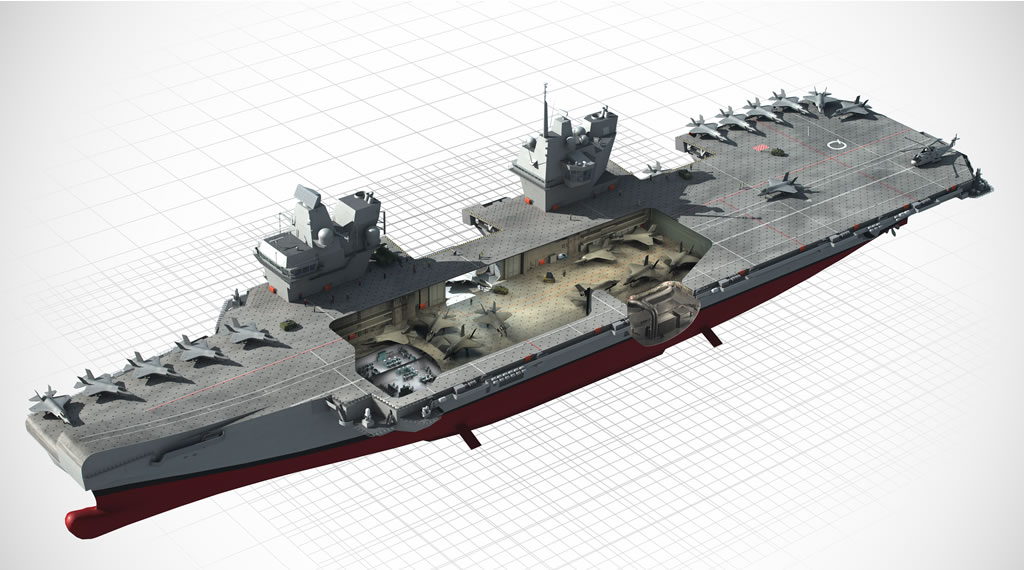

- A computer-generated concept of the proposed KFX stealth fighter (ROK Air Force)

A more pragmatic approach would be to cancel the F-X purchase program and focus on enhancing its indigenous Korean Fighter eXperimental (KFX) program first unveiled in 2011. Since both Indonesia and the United States have agreed to work with the ROK in developing the 5th generation fighter program, the proposed KFX could be less challenging and costly to develop. Such a program could mitigate structural disarmament dynamics and enable a smoother transition if the ROK can eventually afford to purchase the F-35 rather than the F-15SE.

Finally, the ROK could consider a commitment to developing Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAVs) to minimize the potential strategic imbalance. In 1999, when UCAVs were still in incipient stages of development, the Executive Editor of the Air Force Magazine John A. Tirpak predicted that “the UCAV could be smaller and stealthier than a typical fighter…[all at one-third the cost of an] F-35.” Indeed, the ROK plans to revive the “once-aborted program to develop mid-altitude unmanned aerial vehicles (MUAV) to bolster its monitoring capabilities of North Korea’s missile and nuclear programs.”

Contrary to the popular belief among many South Korean defense analysts, the ROK cannot come up with the defense budget to match its rivals. So long as that’s true, the type of stealth fighter chosen will have little or no effect on the ROK’s ability to achieve strategic and tactical air parity with its neighbors. The ROK can, however, avoid severe gaps in air power stemming from potential structural disarmament by reexamining the development of indigenous stealth fighters and UCAVs.

This article was originally published on RealClearDefense and is cross-posted by permission.

Jeong Lee is a freelance writer and is also a Contributing Analyst for Wikistrat’s Asia-Pacific Desk. Lee’s writings on US defense and foreign policy issues and inter-Korean affairs have appeared on various online publications including East Asia Forum, the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, the World Outline and CIMSEC’s NextWar blog.