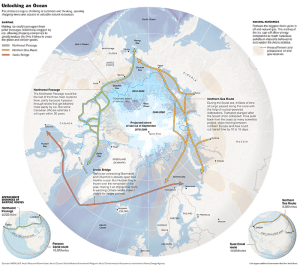

Based on the warming trend in the Arctic Region, large portions of the Arctic Ocean are projected to be seasonally ice free by mid-century; between 2030 and 2050. This warming trend carries with it the risks and opportunities associated with seasonal access to the Arctic Ocean, rivers, and coastline which includes mineral deposits, petroleum resources, fishing stocks, and economically advantageous shipping routes. The central question is how the United States should prepare for the effects of a potential seasonal thaw of Arctic ice by mid-century.

US National Interest

Seasonal access to the Arctic Ocean significantly impacts US national interests. It has the potential to increase national economic security, encourage global economic stability, and create new theaters for global leadership in international cooperation.

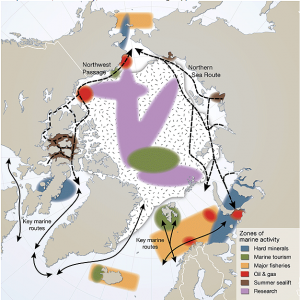

The Arctic region is estimated to have over $1 trillion worth of precious minerals and the equivalent to 812 billion barrels of oil. All of which will become increasingly available for extraction. The U.S. could make great strides toward energy independence by developing these resources within its Arctic territory and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

The Arctic region is estimated to have over $1 trillion worth of precious minerals and the equivalent to 812 billion barrels of oil. All of which will become increasingly available for extraction. The U.S. could make great strides toward energy independence by developing these resources within its Arctic territory and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Actors and Governance

1. Actors

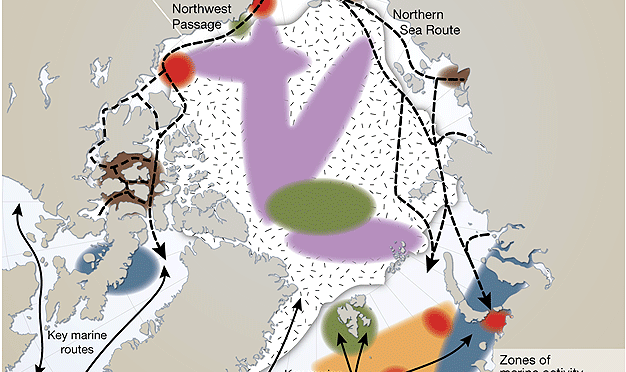

The actors involved in strategic prepositioning for the Arctic thaw fall into two categories. The Primary Actors hold legal rights to Arctic territory in accordance with internationally accepted legal structures. These include the Arctic Nations (United States, Russia, Canada, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Denmark) and indigenous populations (Athabasca, Inuit, Saami, etc.). Influential Actors have significant stakes in Arctic policy outcomes but do not hold legal rights. While some such actors may not yet be apparent, the most obvious are large environmental advocacy groups and multinational corporations in the energy, mining, shipping, and fishing industries.

2. Governance

Governance in the Arctic Region, particularly the maritime domain, remains in nascent form. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) broadly applies international law but does not address unique requirements for Arctic shipping. For example, there are no ship construction specifications or crew proficiency requirements for sailing within proximity to ice fields. Under the United Nations charter, the International Maritime Organization has begun to analyze potential Arctic regulatory actions.

The Arctic Council was established in 1996 as an intergovernmental forum to coordinate Arctic policy and resolve disputes diplomatically. This forum does not establish international law but provides a venue for Arctic Nations to settle bilateral or multilateral disputes as well as coordinate initiatives to be brought before the International Maritime Organization.

At the national level, laws pertaining to environmental protection and the rights of indigenous peoples produce a complicated legal landscape the policy makers will have to navigate in coming years. Shell’s recent decision to postpone drilling operations in the Alaskan Arctic highlights this tension.

Considerations

1. Unclear Impacts of the Thaw

While a seasonal ice-free thaw by mid-century is generally accepted, several second order effects remain controversial or unpredictable. The total magnitude of shipping traffic, intensity of mineral and oil extraction, as well as weather impacts on fishing stocks and agricultural growing conditions are not commonly understood.

Most shipping estimates focus on the economically viable trans-Arctic shipping traffic between North Asia and Europe. By 2030, 1.4 million TEU (twenty-foot equivalent unit) could be transported across the Arctic on 480 total transits. By 2050, a potential 2.5 million TEU could be transported across the Arctic on 850 total transits. The wide array of other potential waterborne activities (i.e., commercial fishing, offshore drilling/exploration service traffic, and tourism) is not adequately captured in shipping estimates.

Most shipping estimates focus on the economically viable trans-Arctic shipping traffic between North Asia and Europe. By 2030, 1.4 million TEU (twenty-foot equivalent unit) could be transported across the Arctic on 480 total transits. By 2050, a potential 2.5 million TEU could be transported across the Arctic on 850 total transits. The wide array of other potential waterborne activities (i.e., commercial fishing, offshore drilling/exploration service traffic, and tourism) is not adequately captured in shipping estimates.

The Arctic warming trend could increase fishing stocks and shift populations northward, thus bringing with it commercial fishing fleets. This trend also may improve agricultural growing conditions across the Siberian plain and allow waterborne bulk transport of product via Arctic rivers. All of these activities could sharply increase the seasonal shipping density in the Arctic.

2. Delicate and Extreme Environment

The Arctic is an extremely fragile ecosystem. The risk of ecological disasters associated with resource extraction and transport will greatly impact the legal framework as well as rate and costs of development for exploitation of Arctic natural resources.

Human disasters will be just as likely. As Arctic infrastructure and maritime traffic increases, so increases the need for responding to human distress. Relief or Search and Rescue efforts in a region with significant radio interference and decreased satellite and GPS coverage will require a multi-national collaboration.

Policy Path Options

The United States can choose from three policy paths: a market-led policy, a regulatory-led, or a blended policy. A market-led path would place the government in more of a reactionary role by regulating as industries develop. A regulatory-led path would establish constraints or enablers ahead of industry to guide market development. The blended path would regulate areas of critical priority ahead of industry but otherwise allow the markets to develop naturally.

Potential Naval Efforts

While national policy seeks to minimize the militarization of the Arctic, the United States Navy could still play a significant role in the development and organization of Arctic maritime shipping management.

1. Lead an Interagency effort to develop infrastructure and regulations to ensure safe navigations of Arctic waters.

At the national level, the Navy could identify site and asset requirements for comprehensive Maritime Domain Awareness across all U.S. arctic territory and EEZ to include weather and ice forecasting suitable for navigation. Once these requirements are identified, the Navy could lead efforts to construct a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the U.S. Coast Guard, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management in order to develop definitions of roles and responsibilities as well as set the framework for burden sharing agreements.

2. Develop multilateral opportunities to enhance disaster response.

At the international level, the Navy could lead the effort to build an increasingly complex set of Search and Rescue and Emergency Response training exercises that include multiple U.S. agencies as well as those from other Arctic Nations.

The aforementioned efforts would ultimately lead to the development of an International Arctic Management Center. This center, with operational nodes near the Bering Strait and Iceland-UK Gap, would be multinational and interagency in nature. The primary roles of this center would be to manage safe shipping transit throughout the Arctic and coordinate multinational emergency response efforts. Management of shipping would include organization of convoys as well as activation and dynamic adjustment of approved shipping corridors based on traffic density, weather, and ice.

Proactive international management of commercial activities in the Arctic will greatly reduce the risk of catastrophic events and improve response to those that occur. Additionally, coordination efforts stand to strengthen cooperation and relations across all Arctic and participant nations, including Russia.

Ryan Leary is a U.S. naval officer and Federal Executive Fellow at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. His opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Navy, or any command.