Yemen’s state weakness due to fragmentation and ongoing conflicts allowed Al Qaeda and affiliates to take and hold territory, possibly enabling them to seize the Port of Aden. If Al Qaeda establishes safe havens in the southern Abyan province, supported by local Yemeni inhabitants, attacks at sea or in near by ports similar to the “USS Cole bombing” in 2000 could become a threat, increasing the danger to Red Sea shipping. Yet Al Qaeda is of secondary concern for the Yemeni government, with secessionist insurgencies in the north and the south threatening the state’s unity. Only a stable Yemen can effectively deny Al Qaeda a stable base in the long run.

In recent years, international shippers taking the Red Sea route have been primarily concerned with attacks by Somali pirates. Those attacks went down from 237 in 2011 to 15 in 2013 due to the Somali governments’ increased ability to fight and deter piracy, among other causes. However, another threat to international shipping in the Gulf of Aden looms. Yemen’s southern coastline is on the Strait of Bab el-Mandeb which links the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, a critical maritime choke point where roughly 8.2% of global oil supply passed through in 2009. Its oil exports, accounting for 70% of Yemeni government revenue, make the country highly dependent on its declining reserves. Yemen is an Al Qaeda stronghold, second only to Pakistan (and possibly Syria more recently). It was a target of the U.S. “drone campaign,” with 94 strikes between 2002 and 2013 (Pakistan: 368). Al Qaeda aims to enforce rigid Islamic legislation in Muslim countries and establish a global Islamic Caliphate. According to its 20-year plan, Al Qaeda aims to subdue “apostate” Muslim regimes such as Saudi Arabia and Yemen. It hosts a franchise in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), establishing safe havens in the governorates of Al Bayda’, Ma’rib, Shabwah, Lahji and Abyan, where it exerts considerable influence.

Yemen’s weak central state

Yet the Yemeni government, headed by Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi since February 2012 after the 33-year rule of Ali Abdullah Saleh came to an end, has to deal with more than Al Qaeda. In 1990, the Yemen Arab Republic in the north united with the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen in the south. United in name, Yemen, however, remained a fragmented entity rife with internal divisions. In 1994, a civil war between Saleh’s north and the secessionist south broke out. In 1997, a group called “Ansar Allah”, emerging from a Zaidi Shia religious organization, confronted the Yemeni government leading to armed uprisings and several rounds of fighting between 2004 and 2010. In late March 2011, the defection of General Ali Muhsin al-Ahmar, the chief military commander in north Yemen, led to a security vacuum in the northwest that Ansar Allah seized to take control of Saada city where it continues fighting Sunni-Salafist tribes. His defection may, however, only be a symptom of the Yemeni state’s retreat to Sana’a, neglecting the north and the south. As a consequence, Hadi has to cope with internal struggles and two rebel movements, constraining his ability to fight AQAP.

Al Qaeda’s terrorism at sea

Al Qaeda’s terrorism at sea emanating from Yemen has a tradition and method. Abu Mus’ab al-Suri, an eminent jihadi strategist, defined several choke points as a target and outlined methods for disruption: blocking the passages using mines or sinking ships in them, threatening movement at sea through piracy, martyrdom operations and weapons.

On the Earth, there are five (5) important straits, four of them are in the countries of the Arabs and the Muslims. The fifth one is in America, and it is the Panama Canal. These straits are: 1. The Strait of Hormuz, the oil gate in the Persian Gulf. 2. The Suez Canal in Egypt. 3. The Bab el Mandib between Yemen and the African continent. 4. The Gibraltar Strait in Morocco. Most of the Western world’s economy, in terms of trade and oil, passes through these sea passages. Also passing through them are the military fleets, aircraft carriers and the deadly missiles hitting our women and children … It is necessary to shut these passages until the invader campaigns have left our countries. […]. — Abu Mus’ab al-Suri, “The Global Islamic Resistance Call“.

On January 3, 2000, members of Al Qaeda attempted an attack on the USS The Sullivans (DDG-68), an Arleigh Burke-class Aegis guided missile destroyer, while in the Port of Aden. Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, a Saudi of Yemeni descent, called “the Prince of the Sea”, was its mastermind. He learned boat-handling and other skills from seafarers in western Yemen, adopted the tactics of the LTTE Sea Tigers, an Islamist insurgency in Sri Lanka, and developed plans to attack in the choke points of the Straits of Hormuz and Gibraltar. He discussed the idea to attack U.S. vessels with Osama bin Laden who sent him to Aden in southern Yemen where he organized the attack on USS The Sullivans. A small group loaded a boat with explosives near USS The Sullivans, however overloading the boat so that it sank, before it could launch the attack. Nine days later on October 12, Al Qaeda avoided mistakes, successfully bombing the USS Cole. The USS Cole (DDG-67), same model as USS The Sullivans, was being refueled in the harbor at Aden when it was attacked, killing 17 sailors and injuring 39. On October 6, 2002, the same tactic worked again. A small suicide vessel rammed the MV Limburg, a French 157,000-ton crude oil tanker, in the Arabian Sea near the southern Yemeni coastal town of Al-Mukalla. On November 22, 2002, al-Nashiri was captured, and he has been held in Guantanamo ever since. Nevertheless, Al Qaeda-aligned groups remain able to attack ships. In July 2010, the “Abdullah Azzam Brigade” launched a suicide attack against the Japanese oil tanker MV M. Star in the Strait of Hormuz, injuring a crew member.

Al Qaeda’s resurgence through soft power

In January 2009, AQAP dramatically increased in strength by merging its Saudi and Yemeni franchises. It has proclaimed Islamic Emirates in the cities of Shaqra, Jaar, Azzan and Zinjibar since 2011, and controls checkpoints in the south. An autonomous enclave, established by AQAP insurgents in the southern province of Abyan in 2011, was overrun by the military in June 2012, although some militants were reportedly displaced to other areas. Hadi was able to recapture Abyan in 2012 and restore limited control over the coastal city of Zinjibar. Abyan could, however, become a staging ground for operations to seize Aden, should the Yemeni military fail to defeat AQAP (sometimes referred to as “Ansar al Sharia”, an alias) in Zinjibar. AQAP’s leadership has recently adopted a “soft power” strategy to take and hold territory. Is has been the frequent goal of AQAP in the south to establish an Islamic state; however, in early 2011, Osama bin Laden opposed the idea in a letter to leader Nasir al-Wuhayshi due to “lack of popular support on the ground”. In April 2011, Adil al-Abab, Al Qaeda’s chief cleric, expressed the need to provide social services such as food and water, as part of the strategy to hold territory. He stated “first Zanjibar then Aden”. Later in May 2, 2011, bin Laden was killed by a US Navy SEAL team in his mansion in Abbottabad, Pakistan, but Wuhayshi continued with his strategy and made an “unprecedented” effort to develop and provide social services such as water and electricity in Jaar and Zanjibar. Even though President Hadi has been confident in his success ridding Abyan of AQAP, the fighting continues to the present date.

Aden’s centrality and the U.S. approach

Indeed, Aden would be a vital strategic asset for Al Qaeda, providing a secure base for attacks in the Gulf of Aden, Bab el-Mandeb, the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. Aden had been a prosperous maritime hub under the British as shipments through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal became an important part of world trade. Yet Aden declined over the last two decades. Because it was mismanaged by corrupt politicians, and Al Qaeda’s attacks on the USS Cole and the MV Limburg drove up the price of marine insurance, international shippers have neglected Aden since in favor of Jeddah, in Saudi Arabia, Port Sudan and Djibouti. Instead of prospering, Aden could remain a “Cinderella of the East”, so argues author Victoria Clark. The U.S. follows a three-fold strategy in Yemen: combating AQAP, development assistance and international support for stabilization. It has repeatedly targeted and eliminated high-profile targets in Yemen, using UAVs, military-led airstrikes and CIA operations.

Yet the U.S. counter-strategy depends on the Yemeni state’s ability to maintain national unity. Yemen’s armed forces, including the navy and the air force, are poorly equipped, insufficiently trained and lack morale, limiting the government’s ability to exert control outside of the capital and ensure territorial sovereignty on land or at sea. Al Qaeda’s new soft power strategy requires a different approach in supporting the Sana’a government: assistance to local administrations, building forces to protect local communities and developing basic services. Al Qaeda might be of primary concern for the U.S., but it is only one of many threats to the Yemeni state. Hadi has, however, concentrated his security forces to fight AQAP and neglected demands of the north and the south. As a result, the national dialogue conference is in risk of failure, increasing the secessionist threat. In turn, U.S. support should not primarily focus on combating AQAP but the ability to unite Yemen as a whole, decreasing the group’s attractiveness as an alternative to the central government.

Sources

- Brynjar Lia, “Architect of Global Jihad – The Life of al-Qaida Strategist Abu Mus’ab al-Suri” (Columbia University Press, New York, 2008).

- Martin N. Murphy, “Small Boats, Weak States, Dirty Money” (Columbia University Press, New York, 2009).

- Victoria Clark, “Yemen – Dancing on the Heads of Snakes” (Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2010).

- Gregory D. Johnsen, “The Last Refuge – Yemen, Al-Qaeda, and America’s War in Arabia” (W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 2013).

- Yoel Guzansky, Gallia Lindenstrauss and Jonathan Schachter, “Power, Pirates, and Petroleum: Maritime Choke Points in the Middle East“, Strategic Assessment, 14:2, July 2011, pp. 85-98.

- Martin Rudner, “Al Qaeda’s Twenty-Year Strategic Plan – The Current Phase of Global Terror“, Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 36:12, p. 953-980.

- International Institute for Strategic Studies, “Chapter Seven: Middle East and North Africa”, The Military Balance 113, no. 1 (2013), pp. 353-414.

Niklas Anzinger is a Graduate Assistant at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs in Syracuse, NY. This post appeared in its original form and was cross-posted by permission from our partner site Offiziere.ch.

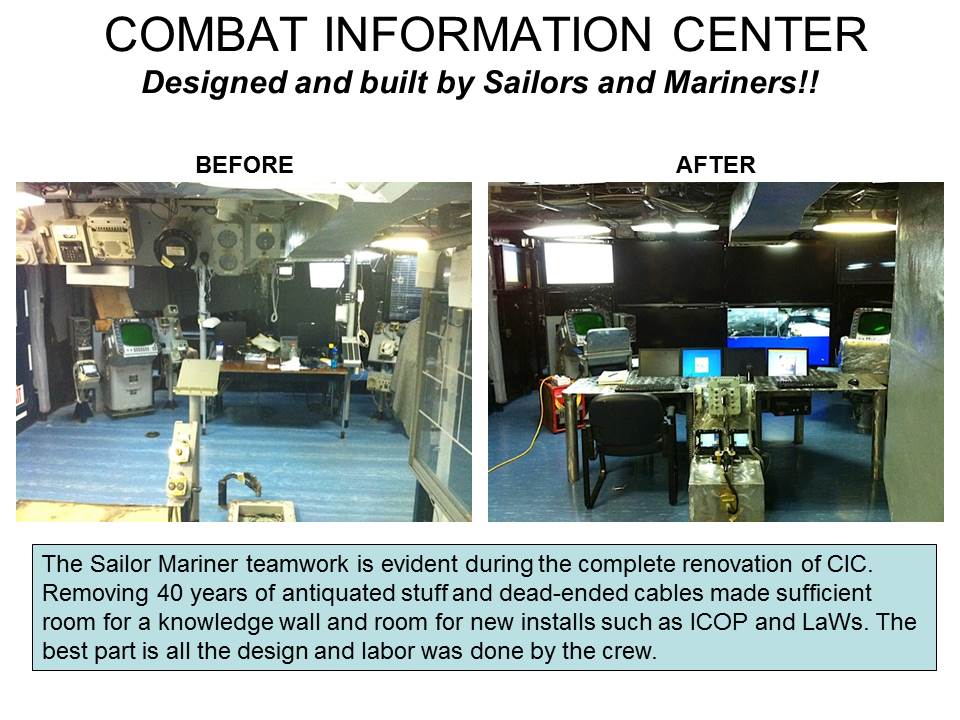

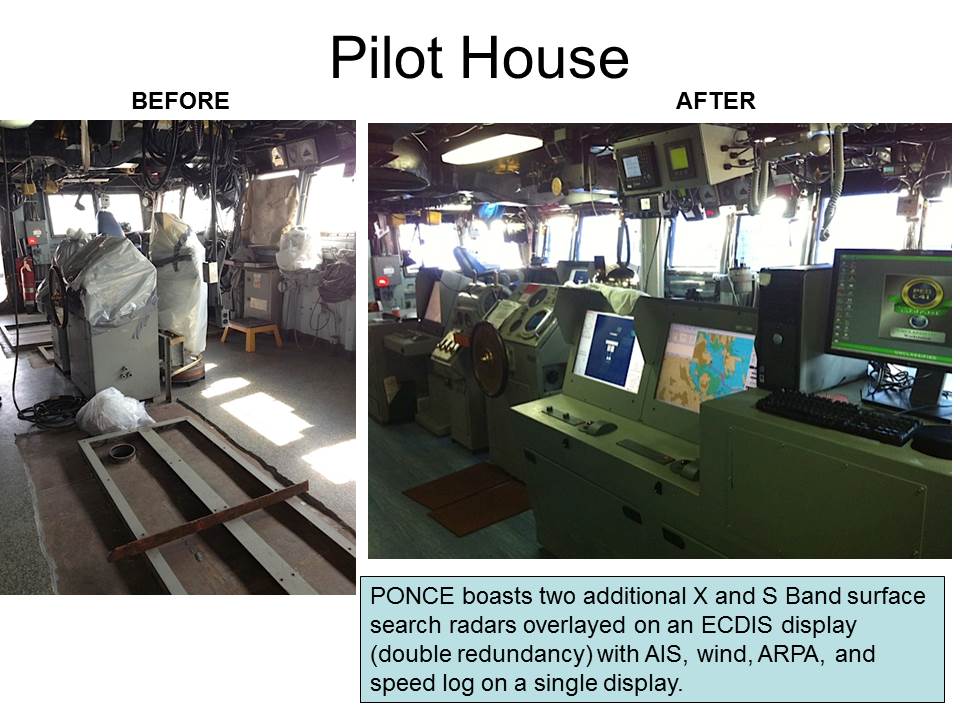

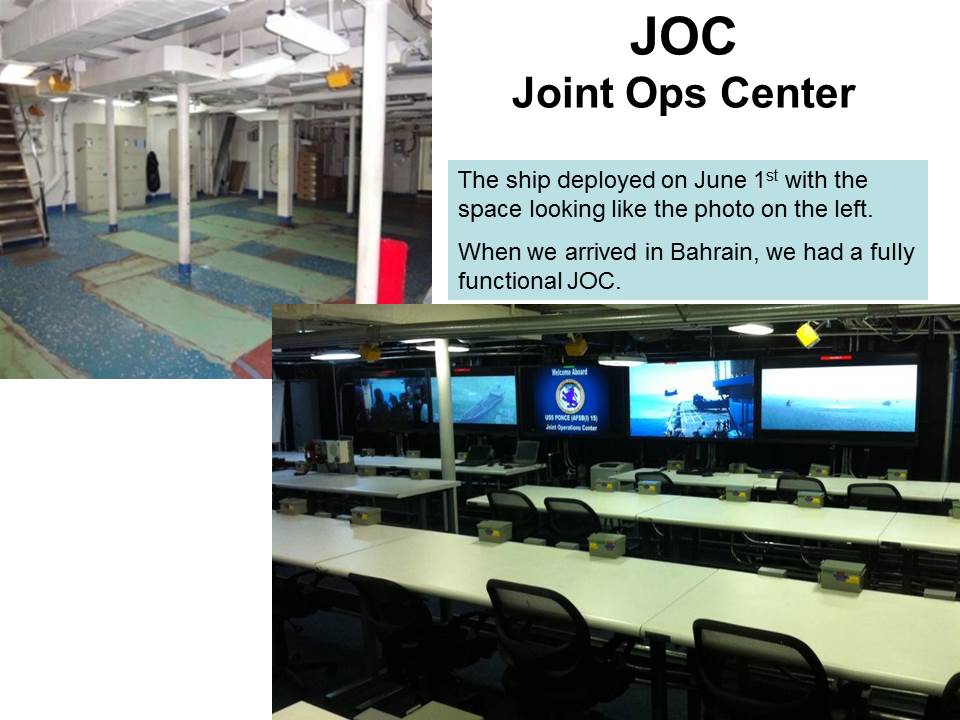

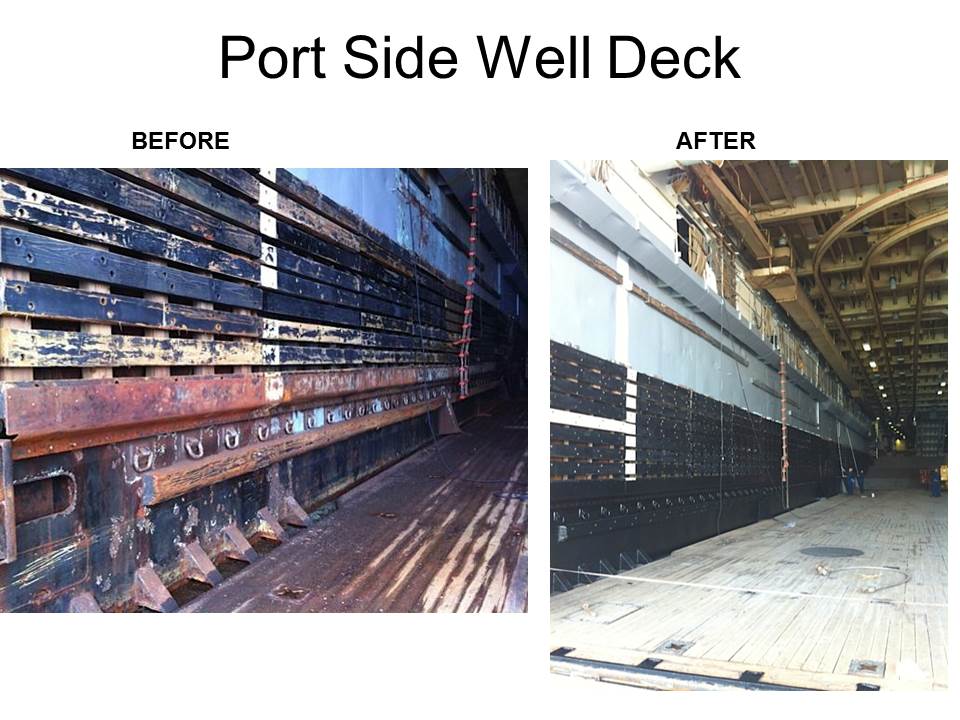

CAPT Rodgers, former CO of the USS PONCE Afloat Forward Staging Base, discusses how his ad-hoc crew of Sailors and civilian mariners plucked a 40 year old ship from decommissioning’s doorstep and turned it into the most in-demand platform in the Arabian Gulf.

CAPT Rodgers, former CO of the USS PONCE Afloat Forward Staging Base, discusses how his ad-hoc crew of Sailors and civilian mariners plucked a 40 year old ship from decommissioning’s doorstep and turned it into the most in-demand platform in the Arabian Gulf.

WarPlan Crimson was the War Department’s operational plan for the invasion of Canada, it is also the long-view schedule for NextWar and its

WarPlan Crimson was the War Department’s operational plan for the invasion of Canada, it is also the long-view schedule for NextWar and its