This article is part of CIMSEC’s “Forgotten Naval Strategists Week.”

It’s time to discuss the Soviet Navy, so dust off your Norman Polmar guides and your early Tom Clancy novels. Or just ask an old salt and Cold War vet if the Red Fleet used to be a big deal. You might even check with Vladimir Putin, who is well aware of this recent yet quickly forgotten chapter in Russian history. Putin would no doubt fondly recall the man responsible for the rise of the Soviet Navy and for its operational and intellectual direction in its heyday: Admiral Sergei Gorshkov.

Gorshkov took command of the Soviet Navy in 1956 at age 45 and oversaw the Soviet Union’s expansion into a global sea power until his retirement in 1985. By comparison, the U.S. Navy had eight Chiefs of Naval Operations (CNOs) during the same period (and potentially more if not for Arleigh Burke’s own unprecedented longevity). Gorshkov’s career demonstrated that he was both a survivor and an extremely patient man. He made it through five Soviet leaders in the post-Stalin period, so he knew how to play his political cards right with the Kremlin. He also survived a defense structure dominated by WWII-era communist party officials fixated on land power and Red Army marshals who were contemptuous and ignorant of naval matters in equal measure. Thus, Gorshkov clearly understood the limits of inter-service rivalry and intellectual rigor within the Soviet system.

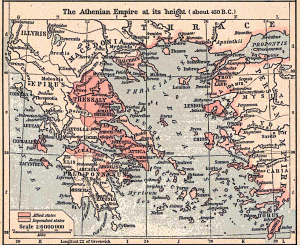

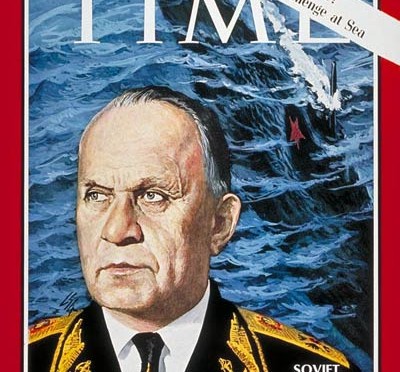

Admiral Gorshkov waited patiently for his opportunity to transform the Soviet Navy from a submarine-dominated, sea denial force with a coastal and defensive orientation into a blue water fleet – though still a sub-centric one – that had strategic strike, power projection, and global presence missions. Above all, the Soviet Navy under Gorshkov had ambitions to challenge U.S. sea supremacy, even if his words did not always match his service’s deeds or capabilities. “The flag of the Soviet navy now proudly flies over the oceans of the world,” the navy chief warned Americans from the cover of Time magazine in 1968, and “[s]ooner or later, the U.S. will have to understand that it no longer has mastery of the seas.” But first, Gorshkov had to achieve mastery over his own navy in the post-Khrushchev era.

An inveterate hater of navies in general, Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev was nonetheless enamored of submarines and presided over the construction of the largest peacetime submarine fleet the world has ever seen (well over 400). After submarines on their own proved to be of limited utility, to put it mildly, during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, Gorshkov capitalized on the humiliation of Khrushchev and of his own navy to press for a more balanced fleet. Gorshkov specifically wanted large surface combatants as well as a greater naval role in Soviet strategy and policy.

It was during the naval expansion period from the mid-1960s through the 1970s under Brezhnev that Gorshkov authored the works that put forth his vision of sea power, Russia’s maritime heritage and destiny, and the naval component of that particular Soviet fixation, operational art. Gorshkov’s writings fueled vigorous debate amongst Soviet naval experts in the West and established a strategic discourse for the superpower naval rivalry that, in hindsight, was truly remarkable.

Contemporary naval leaders and analysts widely acknowledged Gorshkov’s contributions to Cold War naval thought. Gorshkov’s American counterpart in the early 1970s, CNO Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, Jr., encouraged the U.S. Naval Institute to publish Red Star Rising at Sea in 1974. The volume was a collection of 11 articles by Gorshkov published as the series, “Navies in War and Peace,” in Morskoi sbornik (Naval Digest). The article topics spanned from Tsarist times to the Cold War and offered insights on the direction of Soviet naval thinking. Notably, the volume was itself a compilation of earlier Proceedings articles that featured commentary by preeminent American admirals (including four former CNOs) on each of the original Gorshkov articles. As such, Red Star Rising is a time capsule of not only Gorshkov’s ideas but also U.S. perspectives on his philosophy on sea power – as strategist Rear Admiral J. C. Wylie wrote in his commentary, “a rare glimpse into the mind [of the opponent]” – and American reactions to the Soviet naval threat during a crucial period of Cold War naval history.

As the series title implied, Gorshkov presented the case for a strong, balanced fleet with substantial peacetime and wartime missions. The Soviet Navy, in his view, had an especially important role in supporting the Soviet Union’s political objectives and exerting its influence abroad. To not undertake this mission, Gorshkov argued, would cede the ideological battleground to the U.S. Navy as an instrument of “peacetime imperialism.” However, Gorshkov’s real motive, as speculated by experts at the Center for Naval Analyses at the time, was to defend the Soviet Navy’ position internally and to keep its growth trajectory heading upward in the era of SALT and détente.

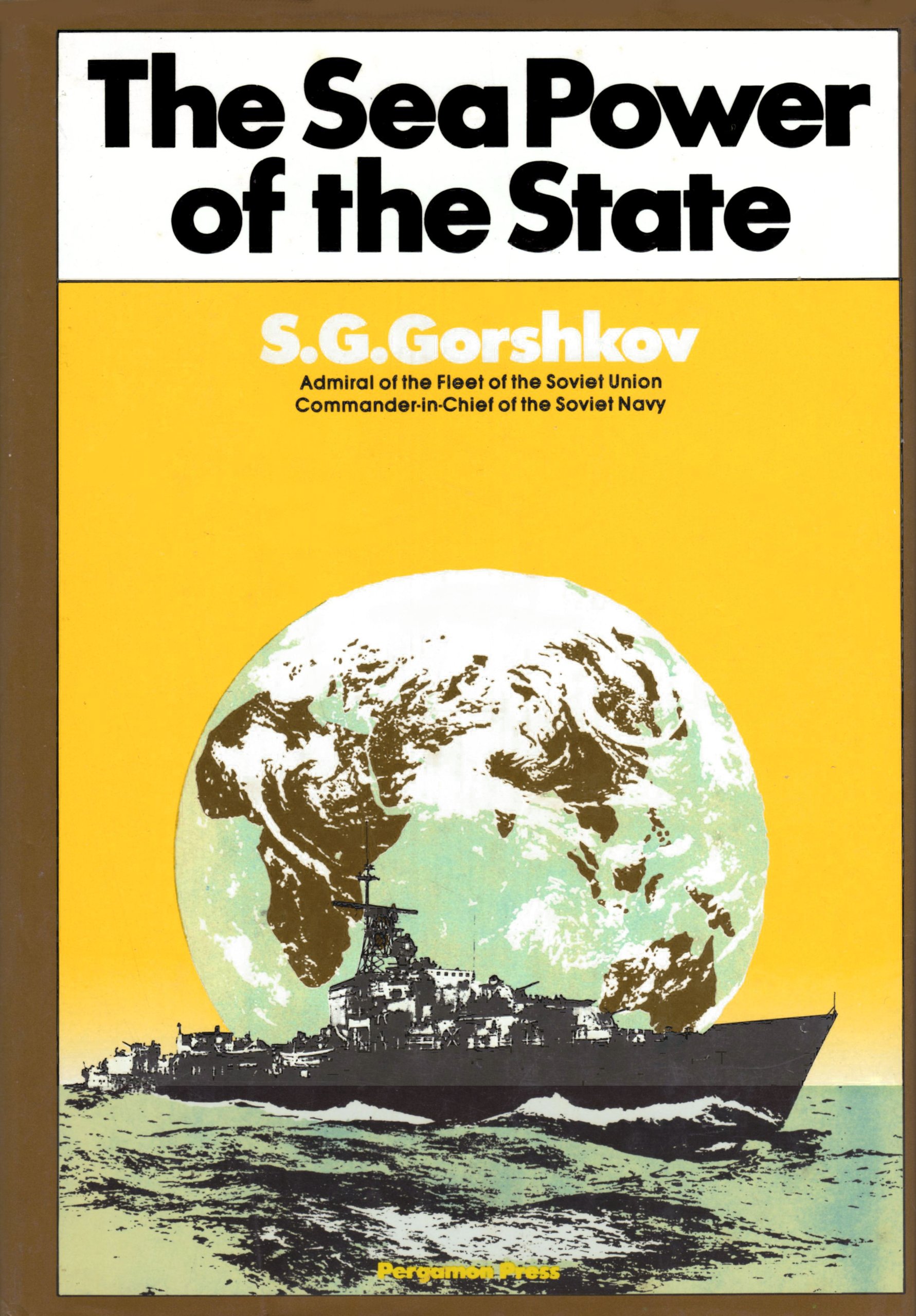

Gorshkov followed up the articles with a book-length treatment of his views, The Sea Power of the State. The book appeared at the height of the post-Vietnam debates over perceived U.S. weaknesses in the face of a growing Soviet naval threat. It also solidified Gorshkov’s reputation as a dominant figure in Cold War naval thought, which was also notable for a Russian’s entry into the maritime strategy realm that was usually dominated by Anglosphere thinkers.

In the book, Gorshkov offered a non-controversial view that sea power provided “the capacity of a particular country to use the military-economic possibilities of the ocean for its own purposes.” He also took the most expansive view possible for what sea power encompasses. His definition not only included the obvious military, merchant, and fishing components, but also the scientific-technical field. Gorshkov emphasized that sea power is also about a link to the ocean environment in an “inseparable union.” To that end, Gorshkov cast himself as an advocate for oceanography and mapping. A visually stunning and expensive series of ocean atlases bore his name as editor during the same period (it was an “opus” that had “all the grandeur and majesty of a Bolshoi production of Boris Gudonov,” according to one American reviewer).

Gorshkov followed three broad principles when marketing his strategic ideas. First, ideas on sea power must be grounded in history. Gorshkov had slim pickings, admittedly, upon which to build a case for Russia as a great maritime nation – unlike Alfred Thayer Mahan’s embarrassment of riches with British history and the Royal Navy – beyond what Peter the Great briefly attempted several centuries ago. Gorshkov also burdened his readers with the usual clichéd Marxist-Leninist dialectic contortions of historical truth. Not surprisingly, his abuses of the historical record were mainly intended for domestic consumption and to overcome the strong land power dogma within Soviet society. Gorshkov vigorously promoted the idea that great powers needed great navies, and so he used history as an appeal to a national identity and a purpose far away from Russian littorals.

Second, Gorshov’s writings indicate that he understood that naval power aspirations must be firmly grounded in theory. Whether it was his earlier use of the term “naval science” in the 1960s, or his later discussions of “naval art,” Gorshkov focused on putting Soviet naval developments and the USSR’s growth as a maritime nation into a larger intellectual framework. This practice was particularly important when Soviet leaders imposed force structure decisions on the Soviet Navy that did not make for sound strategy or even operational sense. To that end, it is possible that Gorshkov likely needed ghost writing help from some brilliant theoreticians and fellow naval officers like Vice Admiral K. Stalbo to reverse engineer theory to fit a desired reality. Gorshkov, helped by allies in the Soviet leadership and by the course of world events, succeeded in carving out a strategic role for the Soviet Navy. Gorshkov made his case most strongly for the wartime missions of long-range naval operations against the enemy’s shore, such as strategic strike and amphibious landings, an area chronically neglected Soviet army strategists.

Finally, Gorshkov grasped what could be called the “optics” of sea power. He believed that ideas are best illustrated with powerful images. He knew, in the best Mahanian tradition, that navies were symbols of great power status and should be used as an instrument of policy. Gorshkov pushed the Soviet Navy’s peacetime role in promoting the interests of the Soviet state and spreading communist influence through presence missions around the globe. An impressive Soviet warship in a foreign port did not raise the same alarms as Soviet tanks or missiles showing up in distant lands. Moreover, navies with a transoceanic reach were an excellent, albeit tremendously expensive, way to coerce allies and confound adversaries. Gorshkov proved to be a master of both outcomes.

In the final analysis, Admiral Gorshkov as a naval strategist is a paradox: his impact on naval thought is at once considerable and negligible. To be sure, Gorshkov ranks among the great naval leaders of the 20th century. He was a consummate planner and innovator in addition to his political skills. He was also a proponent of salami-slicing to achieve his goals long before it became fashionable in the South China Sea. Analysts and historians asked if Gorshkov was a Russian Mahan or a Red Tirpitz to better fit him into the Western canon of naval strategy. There is also no denying that Gorshkov profoundly influenced not only the Soviet thinking on sea power, but also impacted the course of the U.S. Navy during the Cold War. So, as befits the mark of an important naval strategist, Gorshkov’s ideas mattered and were carefully weighed by allies and adversaries alike.

Yet, Gorshkov’s writings lacked the longevity of Mahan’s or Sir Julian Corbett’s works. His appeals to Russia’s sea power potential and its tenuous claims to naval greatness proved ephemeral – and likely helped to push the Soviet state to collapse. Gorshkov’s ideas, in retrospect, reflected a particular aspect of the Cold War and fulfilled their strategic purpose. As a result, Gorshkov is not a source today for timeless lessons on naval strategy, nor are his works still widely read or even discussed in the maritime nations that once followed him so closely. He has been “forgotten” in that sense. Perhaps in the case of Admiral Gorshkov, it is not his writings but his overall approach to the dilemma of a weaker navy challenging a stronger naval power, while at the same time building a maritime foundation and pursuing regional and global ambitions, that is truly instructive.

Chinese naval watchers in the U.S. naturally looked for a Chinese Mahan in Admiral Liu with the rise of China as a naval power. Another potential issue is a Gorshkov-style naval leader and thinker in Asia who understands the limits of his authoritarian state’s naval power, knows how to finesse its lack of maritime heritage, is politically adroit, and can successfully craft the words and images to at least appear to challenge U.S. naval supremacy. Gorshkov’s specific ideas may be of limited use today, but the legacy of his persistence in pounding the square peg of sea power into a land power-centered round hole lives on. His brand of strategic leadership and intellectual engagement could once again tie the U.S. in analytical and operational knots for years to come.

Jessica Huckabey is a researcher with the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA) and a retired naval reserve officer. She is writing her doctoral dissertation on American perceptions of the Soviet naval threat during the Cold War. The opinions are her own and not those of IDA or the Department of Defense.

Join our DC Chapter for its October DC-area informal meet-up/happy hour. We will be meeting at the Hotel Tabard Inn’s Lounge and Bar near the Dupont Circle / Farragut North and West Metro stops to discuss the events of the day (see below) and meet new folk.

Join our DC Chapter for its October DC-area informal meet-up/happy hour. We will be meeting at the Hotel Tabard Inn’s Lounge and Bar near the Dupont Circle / Farragut North and West Metro stops to discuss the events of the day (see below) and meet new folk.