By Scott Cheney-Peters

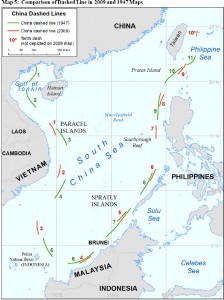

China’s ambiguous claim to the South China Sea, approximately demarcated by a series of hash marks known as the “nine-dashed line,” faced objections from an expanding number of parties over the past two weeks. While a challenge from the United States came from an unsurprising source, actions by Indonesia and Vietnam were unexpected in their tone and timing.

On December 5th, the U.S. State Department released its analysis of the compatibility of China’s nine-dashed line with international law. The report attempted to set aside the issue of sovereignty and explore “several possible interpretations of the dashed-line claim and the extent to which those interpretations are consistent with the international law of the sea.” The analysis found that as a demarcation of claims to land features within the line and their conferred maritime territory, the least expansive interpretation, the claim is consistent with international law but reiterated that ultimate sovereignty is subject to resolution with the other claimants.

On December 5th, the U.S. State Department released its analysis of the compatibility of China’s nine-dashed line with international law. The report attempted to set aside the issue of sovereignty and explore “several possible interpretations of the dashed-line claim and the extent to which those interpretations are consistent with the international law of the sea.” The analysis found that as a demarcation of claims to land features within the line and their conferred maritime territory, the least expansive interpretation, the claim is consistent with international law but reiterated that ultimate sovereignty is subject to resolution with the other claimants.

As a national boundary, the report went on, the line “would not have a proper legal basis under the law of the sea,” due to its unilateral nature and its inconsistent distance from land features that could confer maritime territory. Alternately, although many commentators have indicated China bases its claims on “historic” rights pre-dating the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of 1982, the report argued that the history China points to does not fit the narrow “category of historic claims recognized” in UNCLOS under which historic rights may be conferred. Lastly, the report noted that as China has filed no formal claim supporting its nine-dashed line, the ambiguity over the exact nature and location of the line itself undermines under international law China’s argument that it possesses maritime rights to the circumscribed waters, concluding:

“For these reasons, unless China clarifies that the dashed-line claim reflects only a claim to islands within that line and any maritime zones that are generated from those land features in accordance with the international law of the sea, as reflected in the LOS Convention, its dashed-line claim does not accord with the international law of the sea.”

Although such analysis reflects prior U.S. policy positions, less expected were the pointed signals from Indonesia, which has built a reputation as a mediator among ASEAN states in dealing with China and striven to downplay the overlap by the nine-dashed line of its own claimed exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea from Natuna Island. On Tuesday at the think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, senior Indonesian presidential advisor Luhut Binsar Panjaitan emphasized that the country was “very firm” that its “sovereignty cannot be negotiated,” while stressing the importance of dialogue to peacefully manage matters. Further, in response to a question from an audience member, Panjaitan stated (56:00 mark in the video below) that the development of gas fields offshore Natuna in cooperation with Chevron would “give a signal to China, ‘you cannot play a game here because of the presence of the U.S.’” Meanwhile Indonesian Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Minister Susi Pudjiastuti noted that after sinking Vietnamese vessels the Indonesian Navy said it had captured illegally fishing she was considering sinking 5 Thai and 22 Chinese vessels also caught.

As Prashanth Parameswaran notes at The Diplomat, Indonesia is playing a balancing act – seeking at the same time to protect its sovereign interests as it attempts to align new president Joko Widodo (Jokowi)’s “Maritime Axis”/“Maritime Fulcrum” initiative with Xi Jinping’s “Maritime Silk Road” and play a leading role in China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. To some observers, sinking the Thai and Chinese boats is now necessary to preserve Indonesia’s image of impartiality, while others believe such action may be redundant if China heeds the warning that such behavior will no longer be tolerated.

Vietnam too took surprise action over the nine-dashed line, in a move long-mooted but unexpected in its timing. Vietnam’s foreign ministry announced last week that it had filed papers with the Hague arbitral tribunal overseeing the case submitted by the Philippines, asking that its rights and interests be considered in the ruling. Vietnam supported the Philippines position arguing that China’s nine-dashed line is “without legal basis.” While a regional source in The South China Morning Post noted that the action was as much about protecting “Vietnamese interests vis-à-vis the Philippines as it is directed against China,” and Professor Carlyle Thayer described it as “a cheap way of getting into the back door without joining the Philippines’ case,” Thayer also told Bloomberg News that it “raises the stature of the case in the eyes of the arbitrational tribunal.”

If the actions taken by the United States, Indonesia, and Vietnam were surprising, China’s reactions were not. On December 7th, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a white paper of its own on the Philippines’ arbitration case. The document states that China’s policy, as established in its 2006 statement on UNCLOS ratification, is to exclude maritime delimitation from compulsory arbitration. Additionally, the paper says that while the current arbitration is ostensibly about the compatibility of China’s nine-dashed line with international law, “the essence of the subject-matter” deals with a mater of maritime delimitation and territorial sovereignty. The paper goes on to say that until the matter of sovereignty of the land features in the South China Sea is conclusively settled it is impossible to determine the extent to which China’s claims exceed international law.

If the actions taken by the United States, Indonesia, and Vietnam were surprising, China’s reactions were not. On December 7th, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a white paper of its own on the Philippines’ arbitration case. The document states that China’s policy, as established in its 2006 statement on UNCLOS ratification, is to exclude maritime delimitation from compulsory arbitration. Additionally, the paper says that while the current arbitration is ostensibly about the compatibility of China’s nine-dashed line with international law, “the essence of the subject-matter” deals with a mater of maritime delimitation and territorial sovereignty. The paper goes on to say that until the matter of sovereignty of the land features in the South China Sea is conclusively settled it is impossible to determine the extent to which China’s claims exceed international law.

In effect, China is taking the position that only after it has conducted and conclude bilateral sovereignty negotiations will its nine-dashed line be open to critique. While the foreign ministry may be right that the Philippines is attempting to force the issue of territorial sovereignty, its argument that this prevents scrutiny of the nine-dashed line’s accordance with international law rings hollow.

At the end of the day, China has repeatedly stated, and its new policy paper affirms, that it will “neither accept nor participate in the arbitration” initiated by the Philippines. Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Hong Lei likewise remarked of Vietnam’s filing with the tribunal that “China will never accept such a claim.” So it is prudent to ask what benefit will come of the legal maneuvers. Some, such as Richard Javad Heydarian, a political-science professor at De La Salle University, point to the economic harm already incurred by the Philippines in opportunity costs and the danger of having created a worse domestic and international environment for settling the disputes. Yet given the lengthening list of states willing to stake a legal position on the matter and the moral weight of a potential court ruling, China can claim and attempt to enforce what it wants, but it will be increasingly clear that it is doing so in contravention of international law.

Scott Cheney-Peters is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy Reserve and the former editor of Surface Warfare magazine. He is the founder and president of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), a graduate of Georgetown University and the U.S. Naval War College, and a member of the Truman National Security Project’s Defense Council.

. Also, for those who are interested in all things historical (and naval)

James Goldrick’s latest book, Before Jutland, will be available circa May 2015 through USNI Press. It provides an historical analysis of one of the key periods in naval operations during the First World War.

The Center for International Maritime Security is pleased to announce our first annual Maritime Security Scholarship Essay Contest. In an effort to further our mission of spreading awareness of security issues impacting the ocean commons, CIMSEC is issuing a call for papers from secondary school students around the world. It’s time to put on your

The Center for International Maritime Security is pleased to announce our first annual Maritime Security Scholarship Essay Contest. In an effort to further our mission of spreading awareness of security issues impacting the ocean commons, CIMSEC is issuing a call for papers from secondary school students around the world. It’s time to put on your