This essay is the third in the Personal Theories of Power series, a joint Bridge-CIMSEC project which asked a group of national security professionals to provide their theory of power and its application. We hope this launches a long and insightful debate that may one day shape policy.

Defense industrial base [hereafter “industrial base” or “defense industry”] issues are almost always discussed in a contextual vacuum — as if their history begins with World War II factories or with President Eisenhower’s 1961 warning of a growing industrial complex. But manufacturing materiel is as ancient as war itself. This essay attempts to first set a historical narrative for the defense industry and then to propose a theory of its power.

Marching through history

In 1528, Charles V of Spain hired a Genoese firm to supply and operate a fleet of galleys to help control the Italian coast. Due to their increased size and sophistication, the price of galleys grew. By 1570, this led his son Philip II to experiment with having court administrators operate seventy percent of Spain’s fleet. They failed to recruit experienced oarsmen or to provision equipment efficiently. The price of operating galleys doubled without any vessel improvements before the policy was reversed to private enterprise.[i]

In 1603, Charles’s grandson, Philip III paid 6.3 million ducats to Gonzalo Vaz Countinho, a private merchant, for 40 ships and 6,392 men. This eight year contract supplied Spain with its entire Atlantic fleet. Twenty-five years later, Philip IV contracted a Liège company to build cast-iron cannon and shot. By 1640, 1,171 canons and 250,000 shot were built. Until the end of the eighteenth century Spain was self-sufficient in iron guns.[ii]

Contracting was not limited to the House of Habsburg. Governments have always relied on industry to provide materiel. It is not surprising then that in Michael Howard’s classic War in European History private enterprise plays a prominent role. Knights, mercenaries, merchants, and technologists shaped the history of Europe and thus its wars.[iii]

An industry is born

For centuries supply caravans traveled with armies and small, decentralized, enterprises such as blacksmiths were ubiquitous. To profit, merchants repurposed equipment on commercial markets. Other proprietors assumed financial loss for military titles or, when victorious, profited from the spoils of war.[iv]

The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) changed the scale of conflict and the materiel required to conduct it. At last there were “large-scale profits to be made” from the “business of war”.[v] In Genoa, Hamburg, and Amsterdam centers comprised of weapons manufacturers emerged alongside merchants that specialized in capital, financing, and market access. A multinational arms industry was born that “cut across not just national, but confessional, and indeed military boundaries.”[vi]

Berlin based Splitgerber & Daum was one firm born from this system. Formed in 1712, its two proprietors began as commissioned agents. They raised capital to supply munitions first to local arsenals in Saxony and eventually the Prussian army itself. Their growth can be attributed to an early observation: that success in their business “could be achieved only within the framework of a strictly organized mercantilist economy.”[vii] Patriotism became a marketing tool.

By 1722, Splitgerber & Daum was manufacturing “gun barrels, swords, daggers, and bayonets” at Spandau and assembling guns at Potsdam.[viii] By mid-century it was a conglomerate. Frederick the Great, unlike his grandfather the “mercenary king,” was not an admirer of contractors. But after the Seven Years’ War ended in 1763 he guaranteed the company a “regular flow of government orders” as long as it remained loyal to Prussian interests.[ix] He understood that in order to “raise Prussia to the status of great power required the services of merchants, manufacturers, and bankers.”[x]

Pouvoirs régaliens

Twenty-six years later, the French Revolution would change Europe. Until then, states were the property of absolute sovereigns; after they became “instruments of powerful forces dedicated to such abstract concepts as Liberty, Nationality, or Revolution.”[xi] As the nature of the State changed, so did its wars. French armies were now comprised of conscripts. In 1794, France attempted a planned economy. It reasoned that if people could be conscripted so could resources. The experiment failed due to inefficiency; manufacturing reverted back to private enterprise before the year’s end.

Industry would flourish during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1783 to 1815 two thirds of Britain’s naval tonnage was produced by private shipyards. And the Royal Navy began to experiment with managing industry. It sacrificed deals with large lower-cost providers to bolster small contractors that it considered to be more flexible. In the nineteenth century, the birth of nations launched state industries: private, but British shipyards; private, but German steelmakers.

Krupp would embody this development. Founded in 1811 in Essen (by then Prussia), it would first develop steel. By 1851 it became the primary provider of Prussian arms and, after German unification, the country’s preeminent defense firm. By 1902, Krupp managed the shipyards in Kiel, produced Nassau-class dreadnought armor, and employed 40,000 people.[xii]

Defense Industrial Base Power

Defense industries evolved from distributed providers, to unaligned enterprises, and finally to state-managed industries. They became consortiums of private or government-owned entities that translate the natural, economic, and human capital resources of a state into materiel.[xiii]

World War II stretched this logic to its absolute; all state resources were translated into the machinery of war. In 1940 the US only built 2,900 bombers and fighters; by 1944 it built 74,000 on the back of industry. From 1941 until the war’s end 2,711 Liberty ships were built; welded together from 250,000 parts, which were manufactured all over the country. And from 1942 to 1946, 49,324 Sherman tanks were built by 11 separate companies such as Ford and American Locomotive — built by the “arsenal of democracy.”[xiv]

After the war, all countries began to balance national security objectives with resources via defense industrial base policies. A country’s industrial base capability could be measured as a combination of its scope (how many different cross-domain technologies it could develop), scale (at what quantity), and quality (battlefield performance).

The path to independence

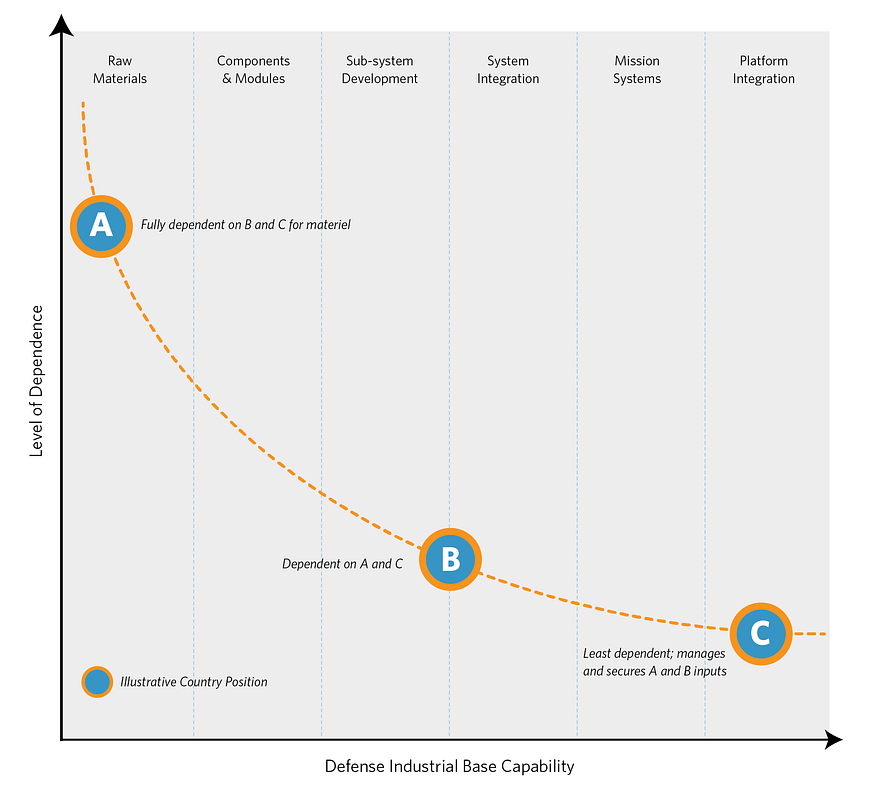

National resources limit capability. Less capable countries are more dependent on allies than more capable ones (see Figure 1). As countries develop an industrial base their level of dependence decreases, but never goes away. This can be best understood through industry itself. Prime contractors rely on their supply chains. But a widget supplier is more dependent on its customer, than its customer is on it.

Figure 1: Interdependence in the International System

Industry developed a science for managing the inherent risk of dependence — supply chain management. However, corporate practices do not translate to international politics. Country A may find new allies; Country B may seek to act on its own. And all countries shift along the curve depending on their level of investment.

For example, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have invested into defense since the first Gulf War. They are now capable of “manufacturing and modernizing military vehicles, communication systems, aerial drones, and more.”[xv] Through offset agreements and foreign partnerships they have acquired “advanced defense industrial knowledge and technology” and are expected to rely on their “own manpower and arms production capabilities to address national security needs” by 2030.[xvi]

To borrow from Henry John Temple — Britain’s Prime Minister from 1859 to 1865 — in the international system, states have temporary friends, but permanent interests.[xvii] Over time, it is thus in the interest of each country to increase its independence by investing into defense capabilities (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Ability to Achieve Political Objectives Over Time

Without such investment, Country Z capabilities erode. Country Y may attempt to sustain its capabilities, but as other countries develop new technologies, sustainment also leads to capability erosion. Only countries that invest into industrial bases over time are able to achieve political objectives independently.

One more supper

The United States has never shown, over a sustained period of time, “a coherent long-term strategy for maintaining a healthy domestic defense industry.”[xviii] American defense budgets are cyclical; they have contracted after every war. Every time, the Pentagon intervened with reactionary strategies to manage industry. And each time, as one former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense noted, the Pentagon got it wrong.[xix]

This was most evident in 1993 when the Pentagon held a dinner, known as the “Last Supper,” with top defense executives. It told them that after the Cold War, America no longer needed nor could it afford the same volume of materiel. But it left it up to industry to decide its overcapacity problem. Industry began to consolidate, based on rational business sense, but not a national strategy.

The 1990s were focused on consolidation, commercialization, and dual-use technology. Today, as budgets are again tightened, new strategies such as increased competition and international expansion have emerged. This may help save some companies, but how will it impact our ability to act independently over time?

In 2003, after decades of following a similar industrial base approach, the UK realized that it no longer had the design expertise to complete development of its Astute-class nuclear submarine.[xx] And in 2010 the UK’s Strategic Defence and Security Review, by listing the capabilities it will have, spelled out what it can no longer accomplish independently. Although the UK received American support for its submarine, what would happen if it did not?

As the US argues over budgets or program cuts, a theory of defense industrial base power could help set priorities. Commercial diversification or international expansion are tactics by which defense firms gain new revenues to save themselves in a downturn. We need a national defense industrial base strategy to maintain our capability for independent action.

[i] Parrott, David. The Business of War: Military Enterprise and Military Revolution in Early Modern Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2012.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Howard, Michael. War in European History. New York: Oxford University Press. 1976.

[iv] Parker, Geoffrey. The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500-1800 (2nd Edition). Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. 1996.

[v] Parrot, The Business of War.

[vi] Howard, War in European History.

[vii] Henderson, W.O. Studies in the Economic Policy of Frederick the Great. Oxon: Routledge. 1963.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Clark, Christopher. Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 2006.

[x] Henderson, Studies in the Economic Policy.

[xi] Howard, War in European History.

[xii] James, Harold. Krupp: A History of the Legendary German Firm. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 2012.

[xiii] Peck, Merton J. and Frederic Scherer M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis. Boston. Harvard University. 1962.

[xiv] Gansler, Jacques S. Democracy’s Arsenal: Creating a Twenty-First-Century Defense Industry. Cambridge. The MIT Press. 2011.

[xv] Saab, Bilal Y. “Arms and Influence in the Gulf: Riyadh and Abu Dhabi Get to Work.” Foreign Affairs, accessed May 5, 2014.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Gartzke, Erik and Alex Weisiger. “Permanent Friends? Dynamic Difference and the Democratic Peace.” International Studies Quarterly (2012): 1-15

[xviii] Harrison, Todd and Barry Watts D. “Sustaining Critical Sectors of the U.S. Defense Industrial Base.” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. 2011.

[xix] Marshall C. Tyrone Jr. “Pentagon Revamps Approach to Industrial Base, Official Says.” American Forces Press Service. February, 20 2013, accessed May 16, 2013.

[xx] Harrison, Sustaining Critical Sectors.

Your monthly East Atlantic edition of Sea Control brings you Alex Clarke with a panel on the state of NATO’s defense spending in the UK and Continental Europe, and whether this spending is sufficient to face our modern threats.

Your monthly East Atlantic edition of Sea Control brings you Alex Clarke with a panel on the state of NATO’s defense spending in the UK and Continental Europe, and whether this spending is sufficient to face our modern threats.