A Chinese military website, ostensibly sponsored by the People’s Liberation Army, quoting Sri Lanka media has reported that a Chinese Type 039 diesel-electric Song-class submarine along with Changxing Dao, a submarine support ship from the North Sea Fleet was sighted berthed alongside at the Colombo International Container Terminal. Although the pictures of the submarine and the support vessel together in the port have not been published either by the Sri Lankan or the Chinese media, it is believed that the submarine arrived in early September just before the Chinese President Xi Jingping’s visit to Sri Lanka. The report also states that the submarine was on a routine deployment and had stopped over for replenishment. Further, a Chinese naval flotilla would call at a Sri Lankan port later in October and November.

In the past, reports about the presence of Chinese submarines in the Indian Ocean have been announced in the media. For instance, the Indian media reported that a type-093 attack nuclear submarine was on deployment (December 2013 to February 2014) in the Indian Ocean and that the Chinese Ministry of National Defense (Foreign Affairs Office) had informed the Indian military attaché in Beijing of the submarine deployment to show ‘respect for India’. Apparently, the information of the deployment was also shared with the United States, Singapore, Indonesia, Pakistan and Russia.

A few issues relating to the presence of Chinese submarines in the Indian Ocean merit attention. First, the Chinese submarine visited Sri Lanka and not Pakistan, a trusted ally of China whose relationship has been labeled as ‘all weather’. The reason for the choice of Sri Lanka could be driven by concerns about Pakistan domestic political instability, which had prompted Xi Jinping to cancel his visit to Islamabad during his South Asia tour last month. Further, the high security risks in Karachi harbour and Gwadar port add to Chinese discomfort.

In the past, there have been a number of terrorist attacks on the naval establishments in Karachi. In 2002, 14 workers of the French marine engineering company Direction des Constructions Navales (DCN) were killed and in 2011, attack on PNS Mehran left three P3C-Orion damaged. The recent report about an attempt to hijack a Chinese-built Pakistani frigate by a terrorist group linked to the Al Qaeda has only reinforced these apprehensions. The Gwadar port is perhaps not yet ready to take on submarines; besides, in the past, three Chinese engineers working in the Gwadar port project were killed in a car bombing and two Chinese engineers working on a hydroelectric dam project in South Waziristan were abducted.

The second issue that warrants attention is that the deployment of the Song-class submarine in the Indian Ocean would be the first ever by a Chinese conventional submarine. This could be a familiarization visit, keeping in mind that the Chinese do not have sufficient oceanographic data about the Indian Ocean. After all, submarine operations are a function of rich knowledge about salinity, temperature and other underwater data. It is plausible that the Pakistan Navy, which has a rich experience of operating in the Arabian Sea, may have shared oceanographic data for submarine operation with the Chinese Navy. Further, the submarine would also get an opportunity to operate far from home and it is for this reason that it was escorted by a submarine tender. It will be useful to recall that China had deployed a number of ships, aircraft and satellite in the southern Indian Ocean in its attempt to locate the debris of MH 370. These factors may have encouraged the Chinese Navy to dispatch the submarine to the Indian Ocean.

Third, if the Chinese are to be believed that they informed Singapore and Indonesia about the deployment of type-093 attack nuclear submarine in the Indian Ocean earlier this year, then the purpose for that was to address the issue of the Southeast Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone (SEANWFZ) also referred to as the Bangkok Treaty signed on December 15, 1995, during the fifth Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit. The nuclear submarine would have entered the Indian Ocean through any of the three straits i.e. Straits of Malacca, Sunda Strait and the Lombok Strait and transited through the SEANWFZ.

The ASEAN countries have been urging the five nuclear weapon states (NWS) – China, France, Russia, United Kingdom and the United States – who operate nuclear powered submarines / warships carrying nuclear weapons, to sign various protocols of the SEANWFZ but have expressed reservations partly driven by the fact that the SEANWFZ curtails the movement of nuclear propelled platforms such as submarines. Indonesia has been at the forefront to ‘encourage the convening of consultations between ASEAN Member States and NWS with a view to the signing of the relevant instruments that enable NWS ratifying the Protocol of SEANWFZ’.

If the presence of Chinese submarines in the Indian Ocean is true, it is fair to suggest that Chinese forays have graduated from diplomatic port calls, training cruises, anti-piracy operations, search and rescue missions, to underwater operations. Further, the choice of platforms deployed in the Indian Ocean has qualitatively advanced from multipurpose frigates to destroyers, amphibious landing ships and now to submarines. The Indian strategic community had long predicted that China would someday deploy its submarines in the Indian Ocean and challenge Indian naval supremacy in its backyard; these concerns have proven right. The Indian Navy has so far followed closely the Chinese surface ships deployments in the Indian Ocean but would now have to contend with the submarines which would necessitate focused development of specialist platforms with strong ASW (anti-submarine warfare) capability.

Dr Vijay Sakhuja is the Director, National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Maritime Foundation. He can be reached at director.nmf@gmail.com.

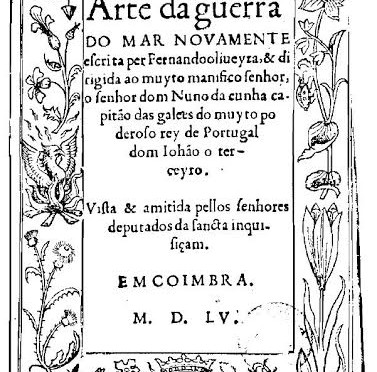

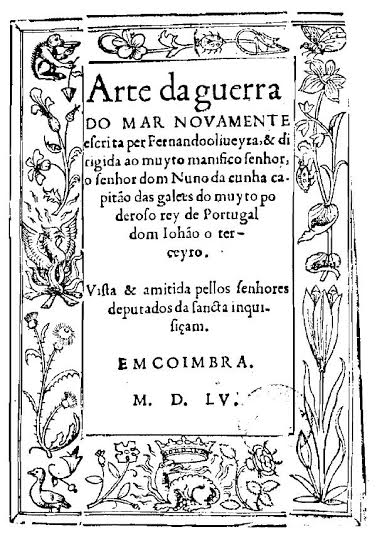

“Art of War at Sea” has one prologue and two parts, each of them containing fifteen chapters. It addresses a broad array of topics, such as naval construction, ship’s commissioning, navigation, seamanship, meteorology, oceanography, logistics, recruitment, training, education, command skills, maritime ceremonial and intelligence.

“Art of War at Sea” has one prologue and two parts, each of them containing fifteen chapters. It addresses a broad array of topics, such as naval construction, ship’s commissioning, navigation, seamanship, meteorology, oceanography, logistics, recruitment, training, education, command skills, maritime ceremonial and intelligence.

We cover the

We cover the