As a Christmas gift from our friends at Risk Intelligence, we’re sharing two free articles from the publication Strategic Insights by CIMSECians. This second (also available in Pdf form), originally appeared in the November 2014 issue and provides a background and maritime risk analysis on the Mozambique Channel.

When considering maritime chokepoints worldwide the Mozambique Channel should come to mind; however, because of greater instability and vulnerability in other geographic bottlenecks it is often overlooked. Yet, for the past millennium, the Mozambique Channel has served as a key transit and trade hub linking the Indian Ocean to the world. Today is no different. This article will examine the history of the channel, its growing importance as a source for fossil fuels, the lack of adequate maritime security from regional governments, and the international efforts to mitigate security deficiency.

Pre-Suez Canal History

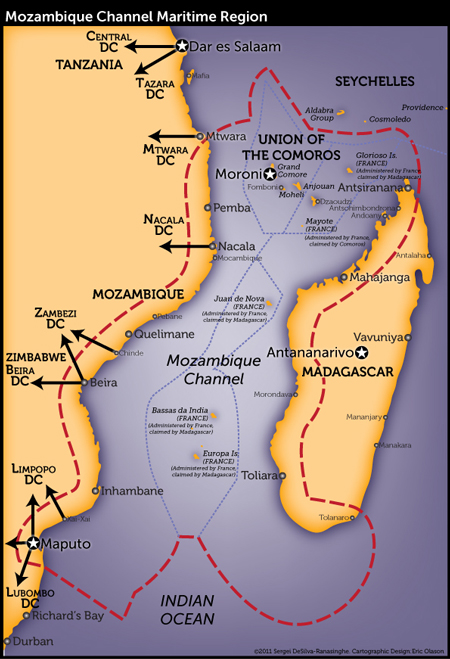

The Mozambique Channel is approximately 1000 nm long and 250 nm wide at its narrowest point. Madagascar, the world’s fourth largest island, forms the eastern boundary, with Mozambique to the west. The volcanic Comoros Islands and the French island of Mayotte lie in the centre of the northern mouth of the channel. The first settlers here were Austronesian seafarers from South-east Asia; next, the great Bantu migration brought Bantu peoples to the Mozambique coast and islands around 1000 CE. In the 11th and 12th centuries, Omani Arab and Persian traders sailed down the East African coast in dhows, establishing trading posts, starting a slave trade from East Africa to the Middle East, and bringing the Islamic faith to what became known as the ‘Swahili Coast.’ The Arab traders were the first, but not the last, to incorporate the Mozambique Channel into the larger Indian Ocean trading sphere.

The Mozambique Channel is approximately 1000 nm long and 250 nm wide at its narrowest point. Madagascar, the world’s fourth largest island, forms the eastern boundary, with Mozambique to the west. The volcanic Comoros Islands and the French island of Mayotte lie in the centre of the northern mouth of the channel. The first settlers here were Austronesian seafarers from South-east Asia; next, the great Bantu migration brought Bantu peoples to the Mozambique coast and islands around 1000 CE. In the 11th and 12th centuries, Omani Arab and Persian traders sailed down the East African coast in dhows, establishing trading posts, starting a slave trade from East Africa to the Middle East, and bringing the Islamic faith to what became known as the ‘Swahili Coast.’ The Arab traders were the first, but not the last, to incorporate the Mozambique Channel into the larger Indian Ocean trading sphere.

Europeans arrived in 1498 when Portuguese explorer Vasco De Gama navigated through the Mozambique Channel on his way to India. In the following centuries the Portuguese established colonies throughout the Indian Ocean basin and East Asia, largely displacing the Arab traders, and used slave labour from Mozambique to supply plantations in Portuguese Brazil and other Indian Ocean destinations. The channel became an international thoroughfare and a critical transit hub for trade linking the Middle East, India, and East Asia with Europe and Brazil.

As the power of France and Britain ascended, ship resupply points in and safe transit through the Mozambique Channel were vital to trade routes with India and the Middle East for both countries. Predictably, pirate havens soon emerged in Madagascar and the Comoros Islands due to their strategic location and the value of passing trade, creating a need for warships to act as protection. Despite prohibition by most countries by 1820, and curtailment of slaving in West Africa, slavers shifted their operations to East Africa and in the 1850s the British Royal Navy and the US Navy regularly patrolled the channel on counter-slave trade deployments.

Whaling was also common. In 1851, an American whaling brig, Maria, was taken hostage in Anjouan, one of the Comoros Islands. The US Navy sloop-of-war, USS DALE, in the area conducting counter-slave trade patrol, responded by bombarding the Island’s defences to release the Maria. By the 1860s, the Mozambique Channel had for centuries played a dominant role in trade within the Indian Ocean and to East Asia and the Western world. Yet to safeguard channel trade and prevent illicit traffic required an international naval response – the same scenario one sees today.

The Most Significant Day in Mozambique Channel History

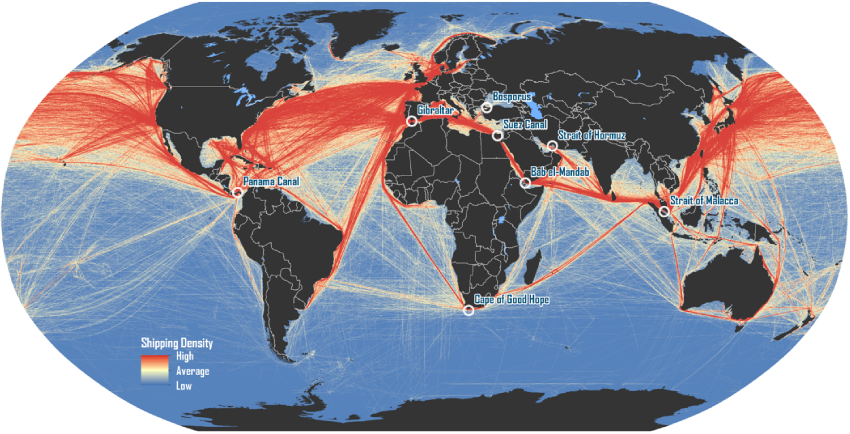

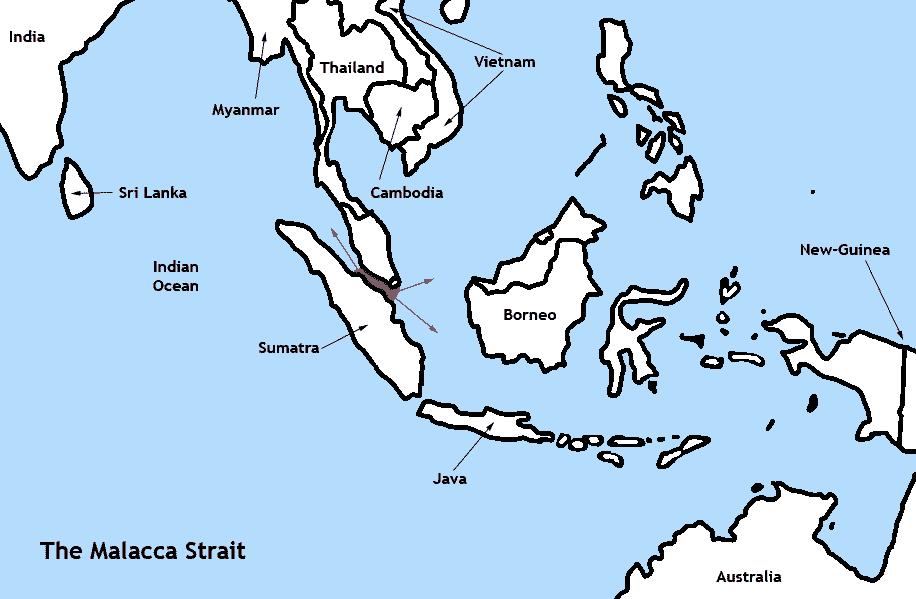

The Suez Canal, opened on 17 November 1869, drastically reduced shipping times and costs for trade between Asia, Europe, and the Americas. This ended the Mozambique Channel’s longstanding and central function as the indispensable link between Asia and the West, relegating it to a supporting role. However, because of the growing threat of terrorism and regional instability, reliance on the Suez Canal causes concern. The September 2013 rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) attack against a merchant vessel transiting the Suez highlighted this. If the Canal closed, the subsequent disruption to trade and immediate increase in shipping costs of re-routing through the Mozambique Channel would significantly increase the price of global consumer goods and oil.

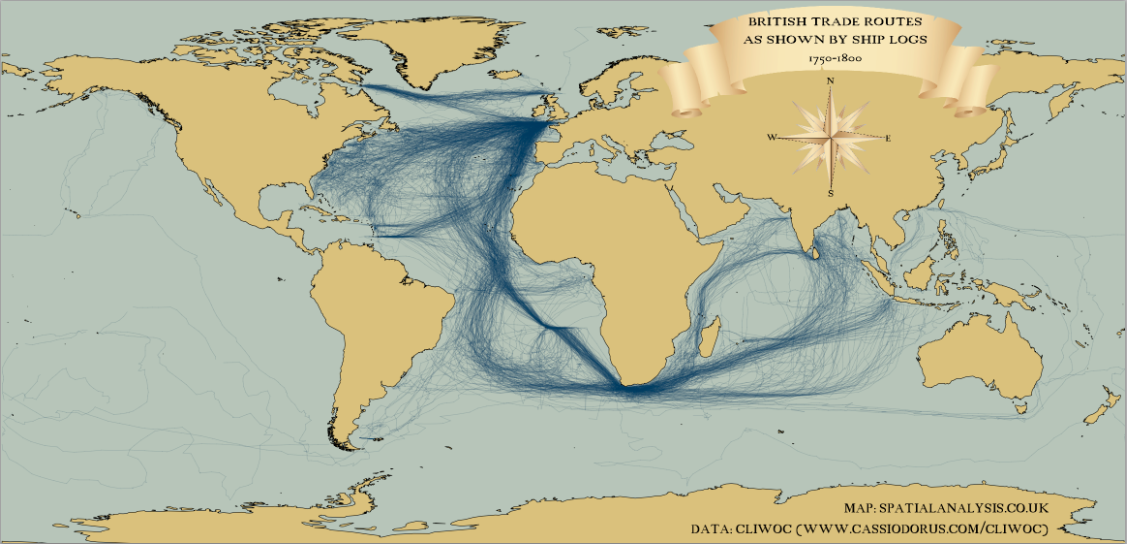

Of course, before the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal, no one questioned the Mozambique Channel’s significance to global commerce – it was understood to be essential. One can see the Mozambique Channel’s role in international trade and traffic from pictured map of British trade.

Post-Suez Canal History

In the 1890s France’s territorial ambitions in the Mozambique Channel set off few alarm bells in Britain, as the French brought Comoros (including Mayotte) and Madagascar into their Empire – Britain’s primary focus had shifted to securing the route to India and the Middle East through the Mediterranean, Suez and Gulf of Aden. However, during World War II, Axis forces in the Mediterranean and North Africa threatened the British supply route to the Indian Ocean, forcing them to use the Mozambique Channel extensively. In fact, the British became so concerned that Vichy France’s Madagascar territory might be used by the Japanese Imperial Navy to harass their vital sea line of communication (SLOC), that they successfully invaded Madagascar in 1942 to ensure Allied control of the Mozambique Channel.

Post-war independence movements reached the Mozambique Channel in 1960 when Madagascar separated from France. Mozambique gained independence in 1975, after fighting a brutal, decades-long guerrilla war against Portugal. The Comoros Islands eventually broke away from France in 1978, with the notable exception of Mayotte, which remains French. After independence, instability continued to plague Mozambique as a violent civil war ensued until the 1990s. Comoros fared only marginally better, experiencing a series of 20 coups from 1978 to 2008 when the African Union intervened militarily to restore order. Madagascar only emerged from its 2009 coup in late 2013. Most of the world viewed these up heavals as internal security struggles that required little attention from the international community, since global maritime transit had shifted to the Suez Canal. Yet today the Mozambique Channel is regaining its status as an important chokepoint, and the resulting maritime security challenges demand international attention.

From Afterthought to Global Hydrocarbon Hub

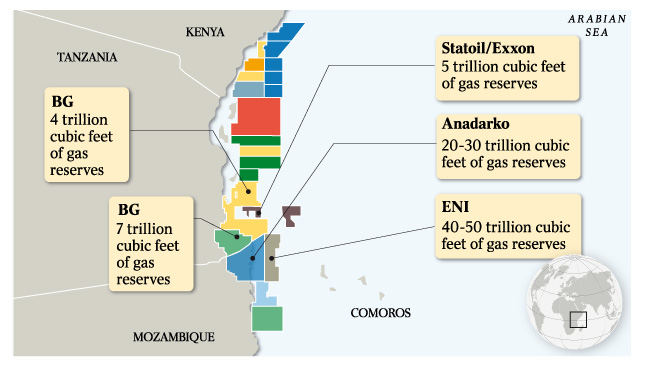

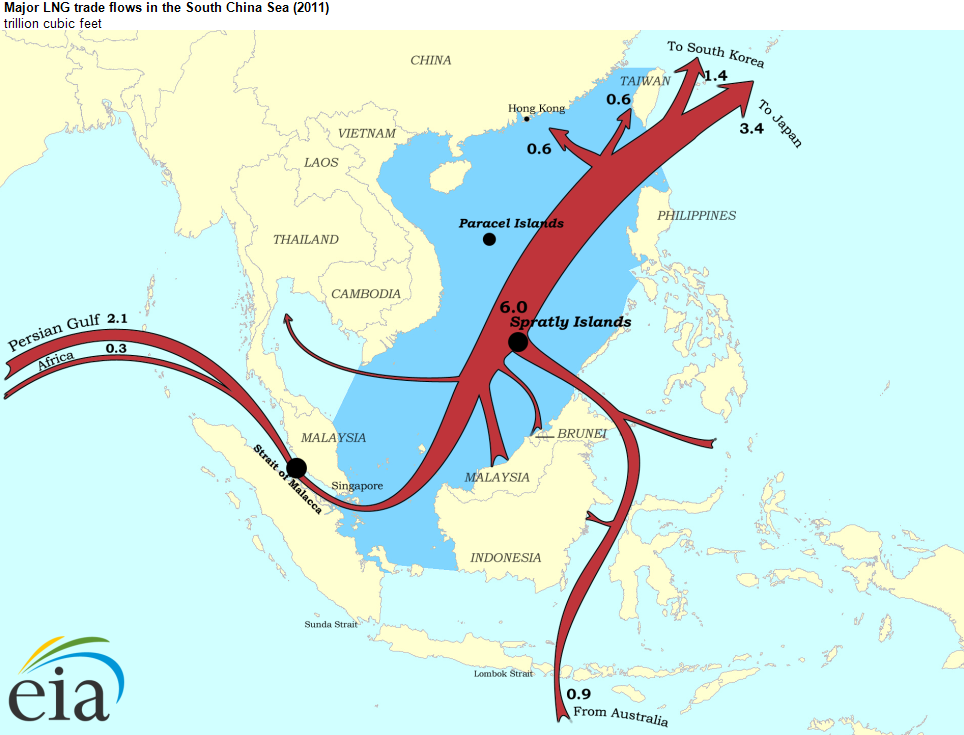

In the past few years, East Africa has rapidly emerged as one of the hottest natural gas plays in the world – and the international interest and investment show no signs of letting up. The offshore region straddling north-east Mozambique and south-east Tanzania, known as the Rovuma Basin, contains, on estimation, over 100 trillion cubic feet of recoverable natural gas, making it one of the largest gas finds in the world. Multinational energy firms have rushed to take advantage of the opportunity. In particular, the US-based energy firm Anadarko and the Italian energy firm Eni hold the two largest offshore investments in north-east Mozambique. Due to the remoteness of the region, the two energy firms have agreed to convert the gas to liquefied natural gas (LNG) onshore in a joint facility for eventual transport via tanker to worldwide markets. The LNG facility is scheduled for operation by 2018 according to company press releases.

The Indian ‘Gulf of Guinea’

The Gulf of Guinea (GoG) in West Africa provides the US and northern Europe with obvious advantages as a source for hydrocarbons: 1) several countries offering favourable terms to private investment 2) short distance to the US and northern Europe compared to Middle East oil; 3) no geographic chokepoints en route. In contrast, Middle East oil has to go through four critical maritime chokepoints (Hormuz, Bab el Mandeb, Suez, and Gibraltar) before reaching the Atlantic. Currently, most of India’s LNG comes from Qatar; thus Mozambique and East Africa could represent India’s equivalent ‘Gulf of Guinea’ – a large natural gas source close to India with no geographic chokepoints, no Middle East political calculus, and with countries open to international investment. Without a doubt, LNG imports will play an increasingly important role in India’s electrical generation mix as India’s growing population and economy demand and expect access to energy. Not surprisingly, Indian oil and gas firms bought significant stakes in Anadarko’s Mozambique holdings. According to ArcticGas.gov (27 May 2014), India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corp (ONGC), India Oil Limited (staterun), and Bharat Petroleum Corp have purchased a combined 30 per cent stake in the Anadarko’s Rovuma fields at a cost of well over $5bn USD.

Not to be outdone, the China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) bought into Eni’s Mozambique lease to the tune of $4.2bn USD for a 28 per cent stake, making the Mozambique play “China’s biggest ever investment in overseas natural gas fields” according to the Financial Times (14 March 2013). Japan and South Korea, both looking globally for alternative sources of LNG, have also invested with both Anadarko and Eni’s holdings; the Japanese energy company Mitsui now holds a 25 per cent stake in Anadarko’s concession and Korean Gas Corp (Kogas) holds a 10% stake in Eni’s concession. Additionally, European Union (EU) tensions with Russia make gas from Mozambique and Tanzania more attractive to the EU members as they attempt to diversify sources away from Putin’s Russia.

To add to the equation, western Madagascar potentially holds billions of barrels of heavy oil onshore and natural gas offshore. As reported by Reuters (07 Nov 2013), ExxonMobil, Total, BG International, and a host of international oil and gas majors have returned to Madagascar to pick up where exploration efforts (both onshore and offshore) left off before the 2009 coup. If exploration yields commercially viable oil and gas, Madagascar might become a hydrocarbon production powerhouse in its own right.

Undoubtedly, critical energy maritime traffic in and around the Mozambique Channel will increase significantly as East Africa transforms itself into a hydrocarbon hub over the next decade. However, the logistics, infrastructure, port facilities, lodging, and support vessels must be created from scratch to support the development. For instance, Anadarko and Eni currently operate two large drill ships in the Mozambique Channel, but security has to be provided by private security companies using their own platform supply vessels (PSV), due to inadequate maritime security capability from area navies, especially in the remote Rovuma offshore region.

Furthermore, the local populace will have to be incorporated into the picture. Populations in the areas around the Rovuma Basin in Mozambique and Tanzania are largely marginalised Muslim communities. Protests and civil unrest in Mtwara in southern Tanzania erupted in 2013 when the country announced a multi-billion USD deal with a Chinese firm to build a gas pipeline from the south to the northern port of Dar es Salaam. As Robert Ahearne states in Think Africa Press (31 May 2013), the chronic grievances in these marginalised areas could become acute as foreign investment pours in and locals see no improvement their lot. The emergence in the mid-2000s of the infamous Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) in Nigeria, which posed a serious threat to Nigeria’s oil revenues because of MEND’s sabotage, piracy, and kidnapping of oil workers, serves as a stark warning. While the Mozambique Channel might not descend into a MEND-style armed insurgency, one cannot rule out an increase in piracy, kidnapping, and harassment as energy production related vessels, workers, and infrastructure flood into an area with a disaffected, impoverished population.

The Comoros Islands pose a similar challenge, with an impoverished Sunni Muslim population of over 700,000 inhabiting a strategic location at the northern mouth of the Mozambique Channel. A prudent course of action would be to engage with moderate Islamic groups and leaders to prevent radical voices from influencing Comorans. Appropriate levels of international and regional engagement with Comoros to enhance maritime security and co-operation should be considered.

Maritime Security

In 2010, during the height of the Somali piracy scourge, the Mozambique Channel experienced several piratical events including the hijacking of an Indian merchant vessel. Despite this, Mozambique can still only occasionally field one vessel capable of patrolling the channel. Madagascar’s navy, emerging from years of government neglect (and virtual isolation from security co-operation with international navies) after the 2009 coup, has even less capability with a few older patrol vessels of questionable value. Comoros has an advanced US-donated patrol vessel, but the high cost of operations and maintenance severely restricts its use. Additionally, these navies and coastguards do not have the fuel and operations and maintenance budgets required to conduct regular patrols of their economic exclusion zones (EEZs).

Typically the channel’s navies stay in port unless there is a distress call or search and rescue (SAR) emergency. The basic calculus is, if the vessels are not underway, then they are not burning fuel or incurring damage. This is a budget-driven decision, not a strategic assessment of the multitude of threats to maritime security and economy in the channel including illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing and illicit trafficking of drugs, people, etc. Last year, however, Mozambique offered a bond for a tuna fishing venture that garnered $80m USD investment due to the high returns, and a French shipyard has been contracted to deliver $300m USD-worth of patrol vessels to be run by private companies to protect this tuna fleet – whether this tuna fleet and associated security vessels materialise remains to be seen (The Economist, 23 November 2013).

Equally limited in the Mozambique Channel is maritime domain awareness (MDA). No Mozambique Channel country uses maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) to monitor the channel regularly. The region also has few automated identification system (AIS) monitoring locations and/or coastal radars. While AIS antennas and systems have recently been installed in Mozambique by the US, the ability to keep them operational (electricity, internet connectivity, maintenance, manning) remains a challenge. French Mayotte offers some MDA capabilities, but the lack of incentive and mechanisms to share the information creates impediments to developing a common, channel-wide MDA picture, leaving MDA severely limited outside of satellite AIS reporting, with patrolling capabilities of regional naval forces sporadic at best. As in the past, regional and international partners have had to step in to ensure the security of the Mozambique Channel.

The Regional Response

While the Somali piracy threat has diminished, the structures put in place during the crisis remain. One of the most important maritime security initiatives is the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) 2009 Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCoC). The DCoC links countries from Egypt to South Africa in an attempt to build regional support structures to improve maritime security through training, information sharing, formalised collaboration, and MDA initiatives (material, exercises, and operations). Despite DCoC’s efforts to build capability, the reality is that the member states’ capabilities to meet its goals remains questionable, especially in the Mozambique Channel, as discussed above.

In 2012, South Africa stepped into the maritime security void with Operation Copper. It signed an agreement with Mozambique and Tanzania for the South African Navy to conduct permanent counter-piracy patrols in the Mozambique Channel and in Tanzanian waters. South Africa also stationed MPA in northern Mozambique to assist with airborne reconnaissance and targeting for the SA Navy frigates and offshore patrol vessels (OPV). In 2013 Tanzania withdrew from the agreement, but the SA Navy deployments continue on a bilateral basis with Mozambique (DefenceWeb, 20 March 2014). Without question, the SA Navy is the most capable force in southern Africa, and its presence in the Mozambique Channel offers a modicum of stability and security. However, South African politicians and observers have begun to question the necessity of continuing Operation Copper in the absence of a clear Somali piracy threat, because of the cost and the need for Mozambique to contribute a legitimate force of their own, (DefenceWeb, 05 March 2014). Should the SA Navy decide to stop Operation Copper, the Mozambique Channel would face serious maritime security and MDA issues – just as the region looks likely to become an offshore energy production and exporting hub.

International Maritime Security Efforts

US and European navies have played a minor role compared with South Africa. The US sponsors the Africa Partnership Station (APS) programme that features ship visits, training, and annual exercises for Mozambique in particular. APS increased US engagement with the region, and the US has used its foreign military financing budget to buy limited equipment (patrol boats, AIS, etc) and training for regional navies. European Union navies also pass through the channel to conduct training, ship visits, and exercises. Most notably, considering Italy’s energy company Eni’s investments in Mozambique, Italy deployed an entire aircraft carrier naval group to Mozambique for two months in early 2014, and signed an agreement with Mozambique to train and operate with the small Mozambique Navy (DefenceWeb 10 February 2014). These arrangements may well continue as Eni’s offshore natural gas field and LNG export facilities come online over the next five years. Meanwhile, through its Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) efforts, France is looking to strengthen co-operation with Comoros, Madagascar, Seychelles, Mayotte, Reunion, and Mauritius on maritime issues included illegal fishing, environmental degradation, etc. Finally, the EU has also recently agreed to restart engagement with Madagascar following the successful election.

US and European navies have played a minor role compared with South Africa. The US sponsors the Africa Partnership Station (APS) programme that features ship visits, training, and annual exercises for Mozambique in particular. APS increased US engagement with the region, and the US has used its foreign military financing budget to buy limited equipment (patrol boats, AIS, etc) and training for regional navies. European Union navies also pass through the channel to conduct training, ship visits, and exercises. Most notably, considering Italy’s energy company Eni’s investments in Mozambique, Italy deployed an entire aircraft carrier naval group to Mozambique for two months in early 2014, and signed an agreement with Mozambique to train and operate with the small Mozambique Navy (DefenceWeb 10 February 2014). These arrangements may well continue as Eni’s offshore natural gas field and LNG export facilities come online over the next five years. Meanwhile, through its Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) efforts, France is looking to strengthen co-operation with Comoros, Madagascar, Seychelles, Mayotte, Reunion, and Mauritius on maritime issues included illegal fishing, environmental degradation, etc. Finally, the EU has also recently agreed to restart engagement with Madagascar following the successful election.

However, one must not forget that the future of the Mozambique Channel will be influenced by Asian countries’ need for resources. The Indian Navy signed a maritime security co-operation agreement with Mozambique in 2012 and opened a ‘listening post’ in Madagascar in 2007 (Asia Times Online, 02 August 2007. See also David Brewster in The Interpreter, 12 July 2012 for India’s broader strategic interests). The Chinese People’s Liberation Army – Navy (PLA-N) has conducted a few port calls in Mozambique, but one can expect greater involvement of the PLA-N in years to come as CNPC’s investments in Mozambique and resources deals with Madagascar move forward. Whether Indian and Chinese security and economic interests can co-exist here will be an interesting ongoing measure of their relative power and influence in the Indian Ocean.

International security co-operation in the Mozambique Channel should also focus on humanitarian assistance/ disaster response (HA/DR). The channel receives regular tropical cyclones, inflicting massive damage and flooding. These pose several maritime issues: 1) environmental response (especially when, as the offshore oil and gas industries increase, so too does the channel’s exposure to damage and spills caused by weather or man-made disasters); 2) SAR – without capabilities to conduct SAR channel-wide, ships in distress will have to hope for merchant vessel or foreign navy aid in extremis; 3) disaster response – should a disaster occur, international navies might be called upon to bring relief.

The historical precedent for international involvement in the Mozambique Channel is clear, and the issues that first confounded the Portuguese, British, and French still largely remain. A proactive international approach to building regional capacity seems warranted in light of the channel’s growth in offshore energy trade, traffic, and infrastructure in the coming years.

Final Thoughts

As long as the Suez Canal remains open and operational, the Mozambique Channel will remain a relative afterthought in global maritime security conversations. Yet the channel looks certain to regain some of its historical significance as a key trade link as the hydrocarbon boom increases maritime traffic volume and value in the channel. Indian, East Asian, and European countries will all come to depend on a steady flow of LNG from and through this chokepoint. Issues ranging from piracy, HA/DR, and illegal fishing will challenge maritime security in the channel for the foreseeable future. Security will have to be underwritten by regional and international partners until the governments in Mozambique, Madagascar, and Comoros make funding viable and operational navies and coastguards a budgetary priority. In the meantime, a better understanding of the maritime history of the region, its importance to future energy markets, and its current security challenges merits focused attention from the international maritime community. Attention, and a few prayers that the Suez stays open.

Louis P. Bergeron serves in the U.S. Navy Reserve and works in his civilian career as a strategy consultant in the national security sector. He obtained a M.A. in Security Studies from Georgetown University in 2011.