By Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson

As it works to improve its maritime militia, Hainan Province is engaged in multiple lines of effort. It confronts many of the same multifarious challenges that other provinces face in constructing their own maritime militia forces. These include strengthening legal frameworks, bolstering incentive structures, constructing infrastructure, and the perennial task of organizing and improving militia training. Hainan thus offers a leading-edge microcosm of the trials and triumphs of Chinese Maritime Militia development, and a bellwether of progress in managing the sprawling effort. Part 1 of this three-part coverage of maritime militia building in Hainan Province surveyed the role of provincial officials and programs, especially at the Provincial Military District (MD) level, as well as their achievements to date; Part 2 now examines in depth the remaining hurdles and bottlenecks that they are grappling with in the process. It will explain specific measures that the Hainan MD is taking to address the abovementioned issues. These include newly promulgated regulations, specific construction projects, breakthroughs in training, increased funding, and examples of the range of direct and indirect benefits maritime militia enjoy through their service.

Challenges in Policy Execution

As explained in Part 1, the Central Military Commission National Defense Mobilization Department (CMC-NDMD) promulgates guidance for nationwide maritime militia work. Provinces, for their part, must flesh out the details in law, plans, and implementation. Numerous reports on the maritime militia by various levels of PLA commands exhort provincial governments to enact more robust laws to help govern the maritime militia. While it is difficult for outsiders to access local laws on the maritime militia, PRC news reports reveal the progress provinces are making in bolstering legal mechanisms for maritime militia mobilization. They often lament the lack of legal basis for fully implementing mobilization work, specifically the lack of legal authority in enforcing and supporting the missions of the maritime militia. One recent report from Zhejiang Province’s Wenzhou City Military Subdistrict (MSD) illuminates these efforts, representing an East China Sea-based case of this broader trend permeating China’s coastal provinces. The Wenzhou MSD struggled to levy fines on maritime militia units that refused to fulfill their duty in training exercises. The abdication of duties by some maritime militiamen triggered an effort by this MSD to evaluate the Wenzhou Court system and the Fisheries Law Enforcement Department, both of which had no legal authority to enact the punishments sought by the Wenzhou MSD.

The MSD therefore established a Maritime Mobilization Office of Legislative Affairs (海上动员法治办公室) to head efforts at drafting local rules and regulations in coordination with the city government. Ensuing maritime militia regulations drawn and passed included “Measures on Maritime Militia Intelligence and Information Incentives” (海上民兵情报信息奖励办法), “Specifications for Maritime Militia Party Organization Construction” (海上民兵党组织建设规范), “Regulations on the Education and Management of Fishing Vessels and Crews on Missions” (任务渔船船员教育管理规定), and other regulations pertaining to the mobilization of reserve forces and requisition of vessels. Troops were reportedly “stunned” when one ship repair yard that refused to cooperate in registering for national defense mobilization was fined and compelled to fulfill its duties. Whereas previous attempts by local military organs to enforce penalties against militiamen abandoning their duties were often described as “loud thunder but little rain,” Wenzhou’s courts now have the teeth to enforce national defense mobilization requisition rules. Additionally, this ordeal shows that military organs have limited legal authority over the militia; and according to Militia Work Regulations (Chapter 8), must rely on local governments or the affiliated enterprise or institution of the perpetrating militia for enforcement. Improved legal measures such as Wenzhou’s allows government and military organs to impose costs for discipline violations in the maritime militia, which directly enhances the maritime militia’s responsiveness and assures their participation in training and missions. The Hainan MD’s leadership has also expressed urgency in strengthening institutional and legal support for its maritime militia development. Specific legal measures appear to be drafted by governments below the provincial level. Like Wenzhou, Sansha City promulgated similar regulations, such as “Measures for the Regular Management of Maritime Militia” and “Rules on the Use of Militia Participating in Maritime Rights Protection and Law Enforcement Actions.”

Significant variation among the economies of each province requires their respective military and civilian authorities to calibrate the incentive structure to motivate their maritime militia units effectively. No single rubric applies, as the Wenzhou MSD discovered when it realized the national standard of fines contained in “Regulations on National Defense Mobilization of Civil Transport Resources” (民用运力国防动员条例) was insufficient to prevent abdication of mobilization duty in economically vibrant Wenzhou. The head of Wenzhou MSD’s Maritime Mobilization Office of Legislative Affairs told reporters in April that compensation for fishing vessel requisition was an example of one area that “requires a great deal of research.” The current standard stipulates that authorities should normally compensate each vessel 10,000 RMB a day, rising to 20,000 RMB a day during the busy fishing season. In Wenzhou’s thriving marine economy, this standard has proven insufficient. The same problem plagued the People’s Armed Forces Department (PAFD) of Yazhou, one of Sanya City’s districts that now host the newly constructed Yazhou Central Fishing Port known to harbor Hainan’s maritime militia forces, as described in the articles on Sanya and Sansha in this series. In addition to hosting Hainan’s maritime militia forces, the Yazhou PAFD has also established its own unit, but experienced difficulties in motivating its unit during the peak period of the fishing season. As Hainan continues to modernize its fishing fleet through vessel upgrades and the replacement of old smaller vessels with larger tonnage fishing vessels, fishing enterprises will attain greater economies of scale. Mitigating lost income due to involvement in maritime militia activities will require increasing compensation.

Parallel efforts to incentivize service help motivate militiamen with financial incentives, including compensation for lost wages, injury, and equipment damage; as well as even reduced insurance costs. A survey conducted by the director of the Sansha Garrison Political Department in 2015 found that 42 percent of Sansha’s maritime militia attached greater importance to “material benefits” than “glory” in their service.

Chinese legislation for the compensation of the military, called the Regulations on Pensions and Preferential Treatments for Servicemen, also applies to the PAP and militia. To further encourage China’s militia to execute their missions, the Ministry of Civil Affairs’ codified the treatment of militia injured, missing, or killed in action in its Measures on the Support and Preferential Treatment of Militia Reserve Personnel Carrying out Diversified Military Missions, effective on 26 September 2014. These measures categorically list the various types of missions and conditions by which the member’s regimental-grade or above PLA commanding unit (county-level PAFDs are regimental-grade units) and the county-level government would determine the status of that member. Missions include supporting the PLA in combat and “participating in maritime rights protection missions.” Militia personnel can be granted the status of “martyr” (烈士), thereby entitling their families to receive money from local governments according to the militia member’s status. For example, survivors of a martyred militia member receive what are known as “Martyr Praise Funds” (褒扬金), equivalent to “30 times the national per capita disposable income.” In addition to “Martyr Praise Funds,” survivors also receive a one-time payment for the member’s “sacrifice in public service” (因公牺牲), equal to 40 months of pay. Under certain circumstances families can also receive annual payments for the militia member’s “sacrifice in public service,” which amounts to a maximum of 21,030 RMB (approximately U.S. $3,235) per the most recent adjustments by the Ministry of Civil Affairs. The military is also allowed to offer other “special payments.”

Militia members are also taken care of and provided for if injured and disabled in the course of their duties. Depending on militia members’ status and the classification of disability they fall under, they (or their families) are granted amounts in accordance with PLA disability compensation under the “Disabled Veterans Special Care Regulations” (伤残军人优抚条例). The standards of compensation are adjusted each year as the national average income changes. According to the most recent national adjustments to the standards of compensation, disabled militia members injured in combat can receive a maximum annual payout of 66,230 RMB (approximately U.S. $10,189) — an extremely generous sum in a fishing village. Major General Wang Wenqing wrote in July 2016 that “we must provide suitable treatment and pensions according to the law for those maritime militia that are injured or sacrificed in the course of their service.” In sum, while a number of regulations already exist to assure militia members their families are taken care of no matter what might happen, authorities continue to optimize incentives for their relatively riskier missions.

Sometimes indirect benefits of service are equally valuable. In a dramatic example, executives of the Sanya Fugang Fisheries Company, home to the maritime militia that harassed USNS Impeccable in 2009, were indicted for numerous crimes of bribery in 2015. Yet Haikou Intermediate People’s Court granted them leniency, citing the extensive service by its maritime militia detachment in protecting China’s maritime rights and interests. Numerous articles written by PLA commanders and officers of local commands call for bolstering the incentive structure for the maritime militia. They suggest various means, including rewarding high-performing units and personnel regarding education, civil service examinations, employment, and promotions. In fact, this is already included in some of China’s regulations, such as in the Martyr Praise Regulations, which explains in detail the preferential treatment of martyrs’ families. Children’s education is supported through reductions in tuition and grade requirements. Regarding survivors’ employment, it states that “local government human resources and social security departments will provide preferential employment services for martyr survivors suitable for employment.” These are just a few examples of the many benefits available to address a variety of negative outcomes for maritime militiamen harmed or killed in the course of their service. Nonetheless, the PLA must rely on local governments to deliver such benefits, some of which—in a problem endemic to the lower levels of Chinese bureaucracy—may not always readily provide such support in the way that the regulations’ drafters envision.

Since the militia are included in China’s national budget, provincial governments have to factor militia expenditures into their budgets. Maintaining a “financial reporting relationship,” the MD logistics departments report militia operating expenses and budget requests to the provincial finance departments for approval. Responding to national militia construction guidance and national maritime strategy, Hainan’s government is devoting increased resources to the maritime militia. In 2013, the Hainan Provincial Government allocated 28 million RMB (approx. U.S. $4,069,767) in special funding for province-wide maritime militia construction. This amount was, in principal, to be matched by county governments, suggesting a much greater total allocation. Correspondingly, reports show that Hainan Government’s defense expenditures have grown significantly, from 65 million RMB (approx. U.S. $9,447,674) in 2015 to over 121 million RMB (approx. U.S. $17,587,209) in 2016, an 88.7 percent boost. While specific allocation of this increased spending remains unclear, a portion of it likely went to further supporting maritime militia construction. Maritime militia bring heightened complexity in terms of financial support largely because of the cost burden of their vessels and professions. Operating costs and risk of injury or loss during normal operations is much greater for maritime militia than for land-based militia.

Multiple sources indicate that plans are underway to construct maritime militia bases, yet remain early in their implementation. MD Political Commissar Liu Xin indicated in late 2015 that sites for developing such bases were being selected and under review. MD Commander Zhang Jian suggests resolving the problem of insufficient support for the maritime militia by “integrating comprehensive supply and support bases with the construction of airports, piers, and the expansion of key islands and reefs in remote waters [in the outer reaches of the Near Seas].” The Hainan Government has approved plans granting a portion of land in Wenchang County for a rear logistics area for Sansha City, including port facilities for its newly built maritime militia fleet. The first phase of the Wenchang County project is a pier-side facility, slated to begin construction in 2017. Those same plans name the Yazhou Central Fishing Port as another harbor for the fleet, which was confirmed in photographs of Sansha City’s new maritime militia fleet mooring there. Public housing is also available for fishermen and workers on-site at Sanya’s new fishing port, conceivably a boon to maritime militia force readiness. Other proposals sent up to the provincial government call for government financial support to construct fisheries logistics bases on China’s newly built artificial islands in the Spratlys, citing the achievements of a key maritime militia unit in Sanya City.

Any infrastructure that is built will certainly be dual-use, and there is great demand for improving facilities to support fisheries development in the Spratlys. Public goods and infrastructure to support Hainan’s marine fishing industry, such as port development projects, benefit its maritime militia forces directly. During meetings of the Hainan Provincial Standing Committee in December 2013 and the 10th Plenary Session of Hainan Provincial Defense Mobilization Committee in October 2014, Party Secretary Luo revealed plans to research and prepare dual-use infrastructure for the maritime militia. Hainan Governor Liu Cigui wrote in August 2016 that Sansha City will expand its grassroots governance organizations from the Paracels to the Spratlys, an initiative also confirmed by Sansha City’s leadership. This effort has also resulted in the construction of a PAFD on Fiery Cross Reef; the lack of any permanent civilian population there suggests that the PAFD exists solely to manage maritime militia. Chinese news reports also confirm a maritime militia presence on Mischief Reef.

Implementing joint military-law enforcement-civilian defense in border and coastal areas likewise requires manned militia outposts to boost security in remote areas. The new construction and reactivation of numerous militia outposts to monitor Hainan’s coast and Chinese-occupied features in the South China Sea was proposed by the director of the Hainan MD’s Training Office Jiang Yongjun. Jiang observes that “maritime defense” (海防) today encompasses a much broader scope and is more demanding than in the past in terms of functions, domains (sea, air, cyber, etc.), and content. This requires outposts at sea and on islands and reefs to serve as additional layers of surveillance and intelligence networks to increase strategic and operational depth. One identified outpost is operated by the Lingshui Autonomous County Coastal Defense Militia, located on Hainan’s Southeast coast on Niuling Mountain. The Lingshui outpost is stated to have developed beyond just a passive watch post into one that provides “active early warning,” thanks to its radar station manned by trained PLA veterans. Recording and identifying vessels transiting an area of 6,600 square nautical miles, they regularly update the Lingshui County PAFD concerning this marine traffic. Substantial reclamation and construction on Tree Island and Drummond Island in the Paracels has yielded two new “informatized militia outposts.” Other reports indicate three more outposts under construction: on Antelope Reef, Observation Bank, and Yagong Island.

Training

Training of the militia is conducted according to outlines drafted by the PLA General Staff Department, now a responsibility of the CMC-NDMD. The latest is the Outline for Militia Military Training and Evaluation implemented on 22 May 2007. This was the first militia training outline to stipulate specific training requirements for militia units that specialized in supporting non-army PLA services, such as militia units that train with and support specific PLAN units. Militia training focuses primarily on preparing militia cadres, emergency response militia, and specialized technical militia. Militia cadres, the leaders of militia units and full-time civilians engaged in militia work at the grassroots PAFDs, must not only be knowledgeable about their own training, but also possess the skills to train the personnel in their respective units. Additionally, China’s Militia Work Regulations states that the PLA services and academies should assist the MDs in militia training.

Training is conducted at militia training bases established by county and city PAFDs, or in capable enterprises if the county lacks a militia training base. One of Major General Wang Wenqing’s solutions for resolving training issues was to increase maritime militia use of training bases. Efforts were already underway in Hainan to provide maritime militia with facilities and bases for training. Discussions were held during a military affairs meeting held in September 2012 by Party Secretary Luo Baoming on the topic of “maritime militia building and construction of a provincial comprehensive militia training base.” While the location of the base remains unclear, it may have been established in 2013 in Qiongshan District, Haikou Municipality. Operated by the Hainan MD Training Battalion, this training base held its first week-long training session for 172 maritime militia cadres in June that year. These cadres will return to their units across Hainan to conduct the grassroots training of the bulk of maritime militia personnel. Additionally, news reports indicate that elements of the Sansha Maritime Militia were sent to a militia training base in “northern Hainan,” suggesting that they too received training from this location.

More stringent training standards are also being applied, alongside increased recruiting of technical and professional personnel and veterans into the maritime militia force. One report concerning a unit from a district of Hainan’s capital, Haikou City, explained that some specialized maritime militia personnel became seasick in rough weather due to their lack of experience operating at sea, reflecting greater involvement of professionals from technical institutes and academies in maritime militia operations. To break in the more white-collar maritime militia personnel, this district’s PAFD held most of its training activities at sea. In another instance, members of the Lingshui County Maritime Militia complained about their evaluation scores after their PAFD increased standards and difficulty during training exercises in 2016. To rectify previous discipline violations, the Lingshui PAFD Political Commissar has reportedly dismissed under-performing cadres and personnel and has increased training standards to reflect real combat requirements. He even personally led at-sea training of the Lingshui Maritime Militia in the Paracels and Spratlys for months on end. Diligent PAFD leaders and cadres are critical to ensuring higher quality training standards more aligned with mission operational requirements, thereby increasing maritime militia capabilities and discipline.

The February 2017 news clip below shows Lingshui County Maritime Militia training, led by Political Commissar Xing Jincheng (who holds the rank of Colonel), including at-sea training and the inside of their outpost on Niuling Mountain.

PAFDs strive to hold maritime militia meetings and training sessions during the offseason to avoid imposing economic losses on maritime militia members, as holding up a vessel at pier-side can cost its owner tens of thousands of RMB in forgone fishing income. They must also account for the training schedules of active duty units in order to coordinate militia training with the PLA. The Hainan MD leadership describes maritime militia training with the following formulation: “fishing and training while at sea, concentrated training in rotations while in harbor, selected opportunities for joint training, regular three-lines joint training, and intensified assault training when on the brink of war” (出海边鱼边训、在港集中轮训、择机拉动合训、定期三线联训、临战突击强训). Commander Zhang specifies that the MD system leads basic training on land, while special training at sea is facilitated by the PLAN and China Coast Guard (CCG). Limitations in available data make it difficult to ascertain the true extent to which the PLAN or CCG trains the maritime militia. For example, an older report from the 2007 Sanya City Yearbook states the Yulin Naval Base worked with the PLA Garrison in Sanya City to train over 1,178 militia members in two years, yet lacks details regarding the content of the training.

Militia units or personnel with more specialized training requirements may be sent to receive further training from the MSD, MD, or active duty troops stationed in the province. Units with a greater demand for technical specialization or coordination with PLA services can obtain assistance from the MD to make arrangements for such training. As reported by the South Sea Fleet Headquarters Military Affairs Department, PLAN active duty units coordinate with MSDs and PAFDs to train maritime militia “specialized naval militia detachments” (海军民兵专业分队). While militia training requirements are outlined at the national level, the specific arrangements at the local levels are suitably tailored to ensure militia units receive the training they need and the PLA has an operationally effective militia force at its disposal.

Training in Joint Military-Law Enforcement-Civilian (Jun-jing-min) Defense

Efforts to incorporate maritime militia forces from the Hainan MD into large scale joint military-law enforcement-civilian defense exercises are reflected in the following recent exercises:

- August 2014: A water garrison district (水警区) of the PLAN South Sea Fleet (SSF) organized a military-law enforcement-militia joint exercise in the Gulf of Tonkin involving various naval ships and aircraft, PLA Air Force (PLAAF) elements, law enforcement cutters, and maritime militia. The live-fire exercise simulated joint escort for a convoy of transport ships as well as the defense of a security zone set up around a drilling platform. The numerous threats presented included enemy ship ambushes and approaching fishing vessels and frogmen.

- November 2014: The Hainan MD organized a military-law enforcement-militia joint exercise at an undisclosed location in Hainan involving “tens of thousands” of personnel across multiple bureaucracies. The theme of this exercise was to prevent the landing of enemy agents by using People’s Armed Police forces at their landing site and CCG ships and maritime militia fishing vessels to repel the enemy landing force. This exercise was designed primarily to practice coordinating various forces under a joint command system and involving local military and civilian leaders directly in the command of local forces, rather than passing them off to the military.

- July 2016: A PLAN SSF Base organized an exercise for defense of “an important location” (要地防御实兵对抗演习). This included anti-air defense forces, shore-based missiles, fighter aircraft, submarines, mine warfare, special forces, local security forces, and both land-based militia as well as maritime militia. Some of the maritime militia involved are identified as belonging to a unit in Sanya City’s Tianya District, suggesting that the exercise was organized by the Yulin Navy Base in Sanya City.

- August 2016: A naval district of the PLAN SSF organized another iteration of the same type of joint exercise held in August 2014, again focused on escort and defense of an oil rig in the Gulf of Tonkin. Asserting that joint defense command and coordination methods are improving, this exercise displayed greater intensity than the 2014 exercise. Intensified contested conditions, mine warfare, and submarine warfare were introduced, attempting to improve and expand joint operations in the South China Sea. All services were involved, including even PLAAF H-6 Bombers, which flew overhead.

Two of these joint training events were organized by the PLAN South Sea Fleet and appear modeled on the May 2014 HYSY-981 oil rig incident. Active involvement of maritime militia alongside some of China’s most advanced platforms—in exercises that simulate recent events that brought the PRC and Vietnam to the brink of conflict—reflects serious approaches to integrating the maritime militia into the nation’s joint maritime forces.

Conclusion: Making Patriotism Pay

Part 1 illustrated how developments in national militia construction guidelines were adopted by China’s key maritime frontier province and how Hainan’s leadership envisions the operational use of its maritime militia. This article, Part 2 in a three-article series evaluating Hainan Province’s overall development of its maritime militia, has introduced some of the major impediments that could hinder the successful construction and use of maritime militia forces in China.The Hainan MD is actively addressing these challenges to ensure its maritime militia is effectively incentivized even in the event of individual members’ injury or death in the line of duty, receives sufficient training both independently and with active duty forces, and has access to civil-military dual-use infrastructure that will give these forces a solid foundation from which to launch required missions. The economic benefits from port infrastructure developments in Hainan will directly improve the commercial underpinnings of its maritime militia. A growing network of militia outposts is improving the militia’s abilities to monitor nearby waters. PAFDs are moving in-step with Sansha City’s effort to expand grassroots governance structures throughout Chinese-occupied features in the Paracels and Spratlys, thereby providing a PLA presence for on-the-ground militia management. Advanced training practices at bases and with active duty forces are incorporating Hainan’s maritime militia into its joint military-law enforcement-civilian defense planning. Challenges may become increasingly acute as its maritime militia forces grow in technical sophistication and require more intense or tailored training, likely placing a heavier burden on the Hainan MD. Any ambitious use of the maritime militia must be supported with the right mix of incentives, a continual focal point in the militia work of local civilian and military authorities that is slowly becoming more regulated. With the overall national guidelines for militia work and specific measures to see its implementation having been examined, the next and final installment in this series will present some of the results of these efforts as well as discuss other potential factors driving maritime militia building. It will also raise additional considerations for assessing China’s Maritime Militia more broadly.

Conor Kennedy is a research associate in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. He received his MA at the Johns Hopkins University – Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies.

Dr. Andrew S. Erickson is a Professor of Strategy in, and a core founding member of, the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. He serves on the Naval War College Review’s Editorial Board. He is an Associate in Research at Harvard University’s John King Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies and an expert contributor to the Wall Street Journal’s China Real Time Report. In 2013, while deployed in the Pacific as a Regional Security Education Program scholar aboard USS Nimitz, he delivered twenty-five hours of presentations. Erickson is the author of Chinese Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile Development (Jamestown Foundation, 2013). He received his Ph.D. from Princeton University. Erickson blogs at www.andrewerickson.com and www.chinasignpost.com. The views expressed here are Erickson’s alone and do not represent the policies or estimates of the U.S. Navy or any other organization of the U.S. government.

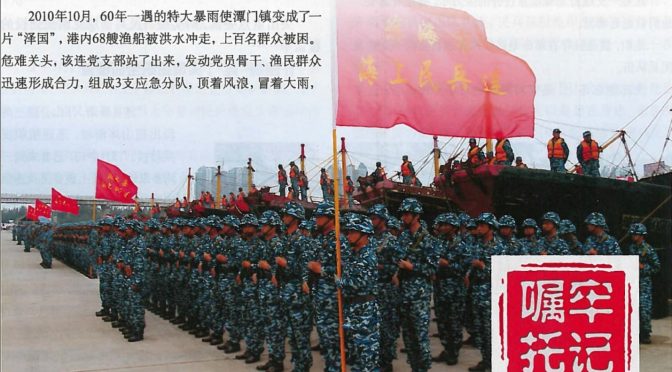

Featured Image: Image of the Tanmen Maritime Militia Company in the July 2016 edition of China’s Militia.