1980s Maritime Strategy Series

By Dmitry Filipoff

CIMSEC discussed the 1980s Maritime Strategy with Captain Spencer Johnson (ret.), who was instrumental in assembling the first briefed iteration of the Maritime Strategy in 1982. In this conversation, Capt. Johnson discusses how the strategy had to quickly come together to inform Navy programming, how it was received in its initial briefings by senior leadership, and how the Soviet Union reacted to the Maritime Strategy toward the end of the Cold War.

What was your role in OPNAV when the Maritime Strategy got started?

I went back to OPNAV in January of 1982, on completion of a three-year tour in command of USS Bigelow (DD-942). When I arrived in the Pentagon and checked in, I was told I wasn’t going to 965, I was going back to OP-06, because Vice Admiral Arthur Moreau who was OP-06 at the time had told the bureau that I was coming back to 06. I had had a previous tour at 06 and had a tour on the Joint Staff and Moreau wanted me back in OP-06. So back I went.

I went to OP-603, Strategic Plans. I was there for maybe 3-4 months when I got called up and told by Admiral Moreau himself that he had a new job from me. I was going to be the OP-06 liaison to the programming side of the Navy staff. Irv Blickstein said in his interview there was no connection between plans and policy, and the programming side of the house. But in fact in the spring of 1982 there was a connection, and that connection was me.

I sat in on the deputy program review committee (DPRC) meetings, the two-star level on the programming side of the house. I was liaison to all of the programming side of the house, O-90 and O-9, at that level. I had as a counterpart a captain from intelligence, I believe his name was Alexander, who also was a liaison to the programming side of the house.

This liaison position was something new. It hadn’t existed before. I think I was the first one and who knows, maybe I was the last one. But I was it. I was certainly very grateful because I learned a lot about how the vast bulk of the Navy staff works because they are all basically with their noses down in programs and line items within the Navy budget.

What kind of feedback were you able to give from a strategic sense? What input did a strategy office or a strategy person have in that kind of liaison role?

Well, number one, I wasn’t asked too much. But in OP-06, OP-06B would attend the deputy PRC meetings. Our three-star, Admiral Moreau, would attend the 3-star PRC-level meetings, and I was able to back brief them before they attended those meetings as to what was on the table and what was going to be discussed, and so on. And I sat in a chair behind them when that happened.

How did you initially get started on the first draft of the Maritime Strategy?

In late August or September of 1982, I was the one who received the tasking to produce a maritime strategy. The “snowflake,” we called taskings “snowflakes” because it seemed like they fell out of the sky like flakes of snow, landed on my desk. The reason why was because VCNO Admiral Shear, who wrote the snowflake, said that they wanted a maritime strategy presentation as the kickoff for the POM programming season.

This strategy was to inform the programmers as to what they were spending their money for, so they would have an idea of how the aircraft, submarines, aircraft carriers, destroyers, and so on fit into the big strategic picture. So originally the maritime strategy was not intended to be a tactically executable strategy, it was intended to inform the programming side of the Navy staff as to what they were spending money for. And when it did later become a maritime strategy that was being exercised at sea and so on, that was kind of an offshoot of what originally began as a budgetary strategy.

The snowflake landed on my desk because I was the liaison to the programming side of the house, and if this was to be the kickoff to the programming cycle then I was the guy who was responsible. I spent several days producing three legal pad-sized handwritten outlines of what I thought this ought to look like. And to this I brought several advantages. First, I knew the audience it was going to. Nobody else in OP-06 knew the audience the way I did because I attended the meetings. Secondly, I had had three years on the Joint Staff and I was very familiar with the joint strategic planning system from my seat in the director’s office on the Joint Staff. So I drew up an outline of what I thought this ought to look like for our target audience of programmers.

From my time sitting in on programming meetings at the two-star and above levels, I was pretty well convinced that the programming side of the house didn’t know anything about the strategic planning side of the house. What’s more, they didn’t really care very much because after all strategic planners didn’t command or control any money. On their side of the house, what really counted was money. The deputy DPRC-level meetings were chaired by Rear Admiral Joseph Metcalf. He was quite a character, a very salty dog. He ran these meetings.

When OP-06 was tasked to produce a strategic overview, there were a lot of people around that table, including Metcalf, who thought it couldn’t be done. The Navy had never had a global strategy before. Even in WWII it was not a global strategy, it was theater strategies. This was an effort to produce a global strategy that would inform how the Navy was spending its money in the programming cycle. So there were even bets made that we couldn’t do it.

With the outline in hand, I went to my branch chief in 605 and I said, “Sir, this is bigger than me. We’re going to need some help.” I recommended we go across the hall to 603 and enlist them in the effort. Because when we get down to the actual planned consolidation and execution, that’s not in our shop, that’s in theirs. So we walked across the hall and enlisted the help of 603, and that’s where Stan Weeks was. Roger Barnett, who was a commander at the time, and Stan Weeks essentially shouldered the burden in OP-603, and I produced my end from 605.

Now, we only had about three weeks to do this, which is a pretty fast time. We had to beat the deadline of putting this at the beginning of the next POM cycle. We had a hard deadline. So obviously it was split, with everybody in 605 and 603 making their contributions, and 605 was primarily myself. I started out with an overview of the joint strategic planning system and what the joint strategic operation plan, the JSOP, called for in the event of a war with the Soviet Union. And we went through the three tables of forces in the JSOP, the JIL-READ, and the JEEP. JIL-READ was a joint document that stood for the joint long-range estimate for planning. The JEEP was the joint intelligence estimate for planning. We used those two things for background for what we could expect from the Soviet Union in the maritime sense. And then we’ve laid out what the Joint Staff, what the joint planning system expected from the Navy in the course of a global conflict with the Soviet Union.

Here we began to get into numbers. At the time the JSOP called for three different Navy force levels. One was what we actually had. The second was what we would have at the end of the FYDP, in other words, five years down the road. And the third one was what we actually needed.

We had at that time 12 carrier battle groups. If you go all the way to the end to what we actually required, the number was something like 23 carrier battle groups. It was that sort of thing that I laid out. And believe me, none of the flag officers in the OPNAV staff outside of OP-06 had ever seen any of this. So we were at the Secret level, and we were really laying it out. And then we said, ‘But we don’t have that many carriers.’ We have 12, but one of those was in SLEP, a two-year program that essentially rebuilt the carrier for extended service life.

In drafting the maritime strategy, we said in effect we’re going to have 11 carriers. We assume that within 60 days of the opening of hostilities that we can have all 11 at sea. We have 11 carriers to distribute amongst the theaters for their various needs. Then OP 605 took the strategic plan for each naval commander in each theater and laid it down and with maneuver and whatever, could show each theater command how many forces they would have at any particular point in time, beginning with the two carriers in the Mediterranean doing their business in the Eastern Med with the Russians. The Navy would be sweeping out with carriers from the East Coast and attacking the Russians in the far north in the Atlantic and even as far north as the Russian north. We did the same thing with the Pacific. If we had a carrier in the Indian Ocean he would do his business with the Russians in the Indian Ocean area, then sweep around and join the carriers in the Pacific and then going up to the north Pacific.

At that time the Navy was pushing for 15 carrier battle groups and 600 ships. So we did two excursions here. We did one with the 11 carriers that we had, and we did one with the 15 carriers that were in the FYDP, or what the Navy was building toward. We could demonstrate the difference what the Navy could do with 11 carriers versus 15 carriers.

That basically consisted of what we titled the Maritime Strategy. We titled it “the Maritime Strategy” because we took all elements that would participate in this strategy. It was not just the Navy, we wrapped in the Army, the Air Force, and the Marine Corps. And we didn’t ask them, we didn’t say ‘mother may I do this.’ We didn’t have meetings with the other services, we just didn’t have the time. We took what was in the plans and we wrapped them in, and I was a little permissive and imaginative with some things that weren’t even written in the plans.

For instance, in the Maritime Strategy we did a lot of offensive minelaying. And the best minelayer we had was a B-52D bomber aircraft because it could carry more mines than any other aircraft we had in the Navy inventory. So we wrote Air Force B-52s into the Maritime Strategy, we wrote the Marines and the Army into securing islands in the Atlantic and elsewhere. The Marines going first, then being relieved by Army forces so the Marines could push on to other things later in the implementation of the strategy.

We didn’t ask them. We just did it. We wrote it in. And we called it a maritime strategy to indicate this was not just the Navy.

We had to do this very quickly. We had almost daily late-afternoon run-throughs and rehearsals with three or four flag officers. And they included OP-60, our immediate boss Rear Admiral Bob Kirksey, his deputy, Commodore Dudley Carlson, and Vice Admiral Art Moreau, who was OP-06. And we would have these rehearsals, these run-throughs, and it was interesting because it wasn’t so much them correcting Stan Weeks and I, it was really us familiarizing them with what was in it. And so they had it down literally by heart. And so we gave the first presentation in October to the DPRC, at the two-star level, chaired by Admiral Metcalf.

Once the presentation was ready, what happened with those first few briefings? How was it received?

Stan Weeks and I had a presentation ready. We each did about half, and it took a little over an hour to make the presentation. But before almost anyone could say anything afterward, Admiral Metcalf picked up the phone at his end of the table, called the CNO’s office, and said “You’ve got to see this right away.”

We were not prepared for that kind of success. Within 48 hours they had convened a PRC meeting, program review committee, and now we are at the three-star level. This time the meeting is attended by the CNO and the Vice Chief, as well as all of his principal three-stars on the OPNAV staff. This is Admiral Watkins, he is the new CNO.

We made the presentation, and at the end of it there weren’t many questions. Admiral Trost, who was O9 at the time, made one correction to one of our slides where I showed the number of VP squadrons in the Navy Reserve and we had dropped a digit, it wasn’t three, it was 13. That was his principal feedback.

It was very interesting. We opined that we could put 11 carriers to sea within the first 60 days of a conflict, everybody except the carrier in SLEP. Admiral Watkins asked Admiral Dutch Schultz, who was OP-05, the head of Navy Air, “Is that true Dutch, could we do 11?” And Vice Admiral Schultz said, “No, Sir.” And Watkins asked, “Well, how many do you think?” And Schultz said, “I think between four and six, maybe.”

Woah, this really got Admiral Watkins’ attention. He asked, “Why is that, Dutch?” “The answer is that we don’t have enough yellow gear,” (the little tractors that pull planes around the flight deck), “we don’t have enough ammunition, and we don’t have enough aviation spare parts to put more than four or five carriers at sea on a wartime footing.”

What the Navy was doing at the time was that they offloaded that stuff and put it on the guy who was about to go. They were crossdecking it. Not just people, but spare parts, gear, and munitions as well. Vice Admiral Dutch Schultz said, “I just don’t have that stuff to put all those carriers to sea and expect them to fight.”

Admiral Watkins at the end of that meeting laid down a number of mandates. Number one, he wanted all of those deficiencies corrected in the budget cycle. He wanted to be able to put all of those carriers to sea with the munitions, the yellow gear, and the aviation spare parts they required.

Number two, he wasn’t going to buy anything in the program that was to be put together that didn’t support this strategy. Now, this posed a logistics problem for us, because we only had two sets of slides and now we had to provide everybody with copies of the briefing so that they could tune their program submissions to what they thought their role was in executing the strategy.

The programmers were very quiet. In terms of feedback, it was mostly Admiral Trost making his comment about the squadrons in the Navy Reserve and some finger pointing about putting those carriers to sea.

The next thing Admiral Trost said was, “I want this sent to the War College and I want it wargamed. I want it exercised in our active fleet exercises, and I want it updated and reviewed every year.” So those were immediate outcomes from the first time the CNO saw the briefing.

The next time, and this went in rather rapid order, soon after the PRC meeting there was a quarterly meeting of the fleet commanders-in-chiefs. Admiral Watkins took this to the fleet CINCs meeting. The presentation was given by Admiral Moreau, OP-06. The feedback from that meeting was that the fleet CINCs were all delighted with this because they saw their own fleet theater plans mirrored. We didn’t change their plans, all we did was essentially say, “This is the sequence in which they will be executed, and with what forces.”

It got a big upcheck from the fleet CINCs, which I think made the CNO feel a lot better about its viability in terms of becoming a strategy, a tactical-strategic strategy, as well as a programming tool.

The next major briefing was given to SECNAV. Again Admiral Moreau was the presenter. I’m sure the CNO and VCNO and a number of the 3-stars were there when that happened. John Lehman immediately saw this as the rationale for his 600-ship Navy. He ordered, among other things, that all captains and admirals in the Pentagon who are going to make any kind of an appearance before Congress had to see this strategy. Lehman wanted all these people, if you were going to Congress, he wanted you familiar with this, because he was going to go to Congress with it, and he did. So now we presented it in iterations of one or two sessions in the Army auditorium of the fifth floor of the Pentagon.

The next significant presentation we did was we briefed the Strategic Studies Group of the Chief of Staff of the Air Force. Recall that we had written the Air Force into the strategy, and this was us telling them how we had done that. They were delighted. The Air Force was now given a maritime role, which they really hadn’t been pushing before but they had it now.

Then the presentation was given to the Secretary of Defense, Mr. Weinberger, in the Tank. I believe Vice Admiral Moreau was the briefer. We were told move it fast, keep it moving, because Mr. Weinberger is known to drop off to sleep in some of these kinds of meetings. So we kept it fast, kept it moving, and at the end of the presentation when all was said and done, Mr. Weinberger walked out and put his arm around the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Vessey. And he said, “When can I see the Army and the Air Force one?” That turned up the heat on what the Army and the Air Force had been working on for years, called AirLand Battle. And that became the Army and the Air Force concept, which the maritime strategy helped provoke.

The briefing was well-received by all its audiences. The reason why I say that is that this was the first time many of them became privy to what was happening in the plans and policy side of the house. They were being read in on the Navy’s core planning projects. So it was well-received.

Without asking the other services, we brought them in at the beginning. For all of them, it meant a new mission to accomplish or an old mission to accomplish. Major General Tom Morgan out of the Marine Corps Commandant’s staff, he attended every briefing we gave because General Morgan learned a lot from it and took that back to the Marine Corps and learned how the Marine Corps was going to be supported by this Maritime Strategy.

I know that General Morgan and the Commandant were really right on board with this because again we used Marine Corps forces to secure necessary islands that we needed to use for island hopping and other things in the conduct of war in the Atlantic and the Pacific. The Marines were happy that they were being utilized in this manner. On the Atlantic side the Marines were training to go to Norway. We also used the Marines initially to secure basic islands that we had to have like Iceland and Greenland to keep the GIUK gap closed. We put submarines up beyond the gap to attack Russian submarines and even bases up around the northern cape there. In the end the carriers go through the GIUK cap and attack Russia. Not nuclear necessarily, but they attack Russia. The strategy was kind of all-encompassing. I never got the sense the Marines were antithetical to the strategy.

The Air Force bought into this because of their B-52s. Within four or five weeks of producing and briefing the strategy we devised several MOUs, a couple of which I helped write, which gave the Air Force the Harpoon missile, which they added to their B-52s and maritime surveillance aircraft. So they now had an anti-ship punch they could use. Initially I was kind of against giving them Harpoon because every one you gave them was one we didn’t have, and I was told, “Don’t worry, the ones we gave the Air Force were the ones Iran bought before the revolution.” We gave the Air Force this maritime role, and they were delighted. I can’t think of anybody that was opposed to or anti this Maritime Strategy.

If we had not written the other services into it, it would just be a Navy strategy and viewed as a Navy push for budget dollars. But since we wrote everybody else in, I mean we put everybody that had a maritime impact into the strategy. Nobody to my knowledge was left out, even though we didn’t ask them. If we said it was a pure Navy strategy, they would just close the door on us.

Did the Army have some issues with it at this point?

If they did, I didn’t hear about it. We used the Army and the National Guard in occupying Atlantic islands and other islands. We had these islands initially taken and occupied by Marines and then relieved by Army. Places like Iceland, Azores, other places. It was Marines first and then Army coming in behind them.

The Army liked it because we were still protecting from Soviet interference with the convoys to Europe, which were crucial to the execution of the European campaign. They were rapidly convoyed to Europe and the U.S. Navy in the Maritime Strategy was still removing the threat to those convoys that were so important to the execution of the European campaign. And the Army in those days was almost totally focused on central Europe.

How was this Maritime Strategy different than the Swing Strategy?

What was different about the Maritime Strategy was that we simultaneously executed strategy on a global basis. Before that it might have been this theater and then that theater in some form and sequence. But here we simultaneously executed operations in all the theaters.

When we did the Joint Strategic Operation Plan in the Joint Staff, the most contentious annex to the JSOP was Annex K. Annex K allocated strategic lift, both airborne and maritime. It told theater commanders what they were going to get and when they were going to get it. That was contentious. When you added it all up it was about 300 percent more than what we actually had available to use. Annex K had essentially divided it out sequentially rather than simultaneously.

How did you continue to work on the strategy as an assistant to SECNAV Lehman?

After the Maritime Strategy went down, it was not too long after that I got a phone call on a Friday afternoon from my detailer. He said, “Pack up your briefcase and move up to SECNAV’s office, you’re now working for John Lehman.” For the next two years before I went back to sea again I worked in the Office of Program Appraisal (OPA), but I was a special assistant to John Lehman, with the title of “Special Assistant for Policy Implementation,” which was made up.

I essentially wrote a lot of his Congressional testimony. Much of it revolved around the 600-ship Navy and the Maritime Strategy. I also helped with his annual statement before the various committees on the Navy and I wrapped in what the Navy had done in the past year in those statements.

Did you see much conversation and inputs being shared between the programmers and the strategists? Is there an ideal way this relationship should work, any lessons for today?

My guess is they don’t talk much to each other today (but I’ve been retired 30 years). I know in the years when the Maritime Strategy was alive and well, it was still the kickoff presentation for the programmers. It’s probably not the same today because when the Soviets went away and our major adversary disappeared, and the Maritime Strategy became something else, it just may have fallen off the plate. I don’t know. But I will say, when we gave this for the first time, we were really telling something to the admirals and the senior officers on the programming side of the house. It was opening their eyes to something they’ve never seen or heard before.

From the OP-06 point of view, it may not have even been a need-to-know. All these plans were SECRET or above, and they were not planning in the strategic sense, they were procuring the equipment with which to carry out the plans.

In putting together a strategy for the programmers, I assumed they knew nothing. I was pretty well correct in that. Fleet commanders-in-chief, they are planners in their own right for their particular theater. They are familiar with this to a degree. The programmers on the OPNAV staff were not, they knew nothing about any of this.

I had to start with that front part which I guess you could call a tutorial, to bring them into the broader picture. At one of our late afternoon rehearsals very early on, Commodore Carlson suggested that we drop the tutorial to shorten the briefing a bit. But Admiral Kirksey told him no, and that it is critical toward understanding the whole thing. Carlson probably suggested that because he knew this stuff, but nobody on the programming side of the house knew any of that.

You had said that nobody had tried to do this before, this kind of strategy.

As far as I know, something like this had never been done before. Even in WWII, you had the Atlantic, the Pacific, the South Pacific strategies and force allocations, there was no, as far as I can tell, global plan, in Admiral King’s office or anywhere else for the conduct of WWII.

The Maritime Strategy was a global concept of operations that had to be broken down in a further amount of detail by the fleet commanders and the theater commanders. It wasn’t the end all. It was the big picture, if you will.

Before we actually did this, people like Admiral Metcalf were betting that we couldn’t do it. Maybe they thought it was just too big for anyone to wrap their arms around it, I’m not sure. In meshing those theater plans together, that’s where OP 603 really made a major contribution because they were the guys that did it.

How did the Soviets react to the Maritime Strategy?

For a period of years, the Russians watched us exercise the Maritime Strategy at sea, and in 1986 they saw the unclass version in Proceedings. We learned later after the Iron Curtain fell that they believed everything we said we could do in that Maritime Strategy, because it was being practiced.

Admiral Crowe, who was the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, made a trip to Russia. He was a guest of his counterpart in Moscow. The Russians then later came to the U.S., including Crowe’s counterpart, Marshall Akhromeyev. When the Russians came to this country, Crowe took them to an aircraft carrier in the Virginia Capes and they were aboard for the day and watched air operations. They found themselves pretty amazed to be onboard an aircraft carrier, which sparked some more conversations. They believed we could do it.

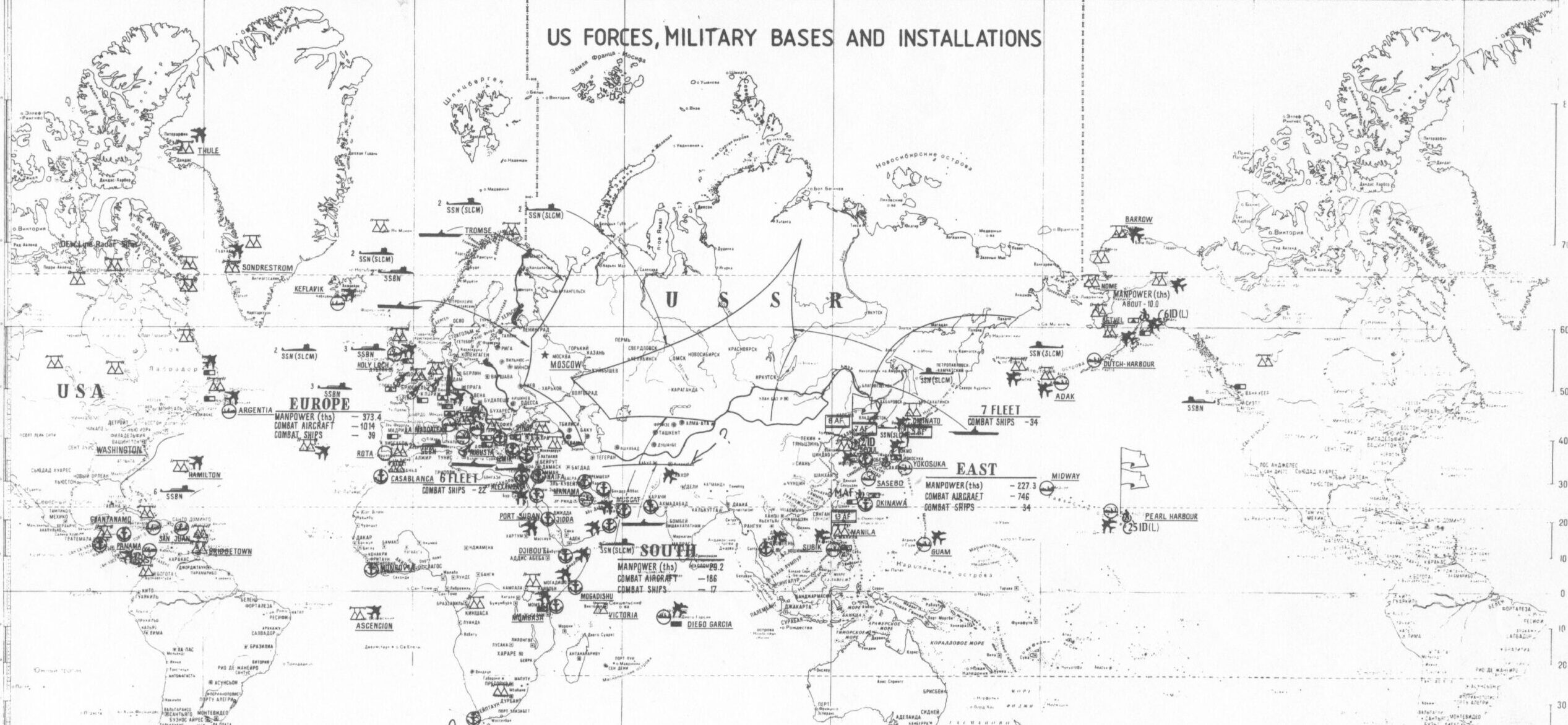

There was a map that Admiral Crowe and others were shown when they visited Moscow. It showed how the Soviets were ringed by the American Navy.

Over the years, up through 1988-1989, our exercises became more expansive. In the Pacific we had combined exercises with the First and the Seventh Fleets, with carriers joining to simulate attacks on Vladivostok and elsewhere. The exercises were becoming larger and more extensive.

The important thing was that the Russians believed it all, that we could do it. The Maritime Strategy in a way acted as a deterrent. That was perhaps the principal, ultimate outcome.

What are the challenges in replicating a similar strategy for today?

We have a different strategic environment today than we did in 1982. We had one major maritime adversary and that was the Soviet Union, and they went away in 1989. Navy maritime strategy then went through a number of fluctuations, such as From the Sea and the focus on littoral warfare and so on.

If you wanted to replicate it today you would have to take in more than one major maritime threat. Today we’ve got Russia and China. You have to reproduce something similar, but now you’re dealing with two major competitors. That makes it more difficult.

I know the Navy is in trouble today with the Congress because the Navy today can’t really explain what it needs and how it is going to use it. We are almost back where we were in 1982, when the Navy had to pull it together.

Captain Spencer Johnson graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1963 and served as a Surface Warfare Officer for 30 years, retiring in 1993. He has served on three destroyers, held command of a destroyer, and commanded a destroyer squadron. He served five tours in the Pentagon, including three tours in OP-06 (Plans and Policy). He has served as executive assistant in OP-06, as special assistant for three years to the director of the Joint Staff, and as special assistant to Secretary of the Navy John Lehman. He holds degrees from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. He concluded his uniformed service as Chairman of the Department of Strategy and Operations at the National War College.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at Content@cimsec.org.

Featured Image: November 1, 1987 – An aerial view of Battle Group Echo in formation. The ships are, from the left, top to bottom, row 1: USNS HASSAYAMPA (T-AO-145), USS LEFTWICH (DD-984), USS HOEL (DDG-13); row 2: USS KANSAS CITY (AOR-3), USS BUNKER HILL (CG-52), USS ROBERT E. PEARY (FF-1073); row 3: USS LONG BEACH (CGN-9), USS RANGER (CV-61), USS MISSOURI (BB-63); row 4: USS WICHITA (AOR-1), USS GRIDLEY (CG-21), USS CURTS (FFG-38); row 5: USS SHASTA (AE-33), USS JOHN YOUNG (DD-973) and USS BUCHANAN (DDG-14). (Photo by PH3 Wimmer via the U.S. National Archives)