How should we scope and understand the dynamic processes behind innovation, in order to better set ourselves up for success? Stealing from John Boyd’s formulation of “people, ideas, and hardware”, let’s add some more nuance, and consider a simple and universal model of change in social systems. We’ll start by artificially separating the world into three basic categories: groups (bureaucracy, incentives, processes, etc), ideas (doctrine, concepts, narratives, etc) and tools (tech, infrastructure, etc), and simulate them evolving and interacting with each other on a left to right timeline.

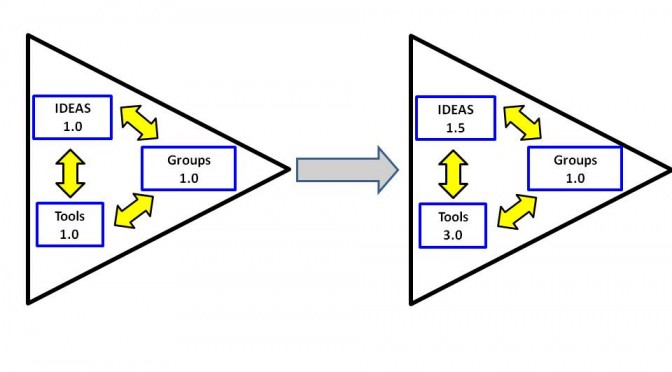

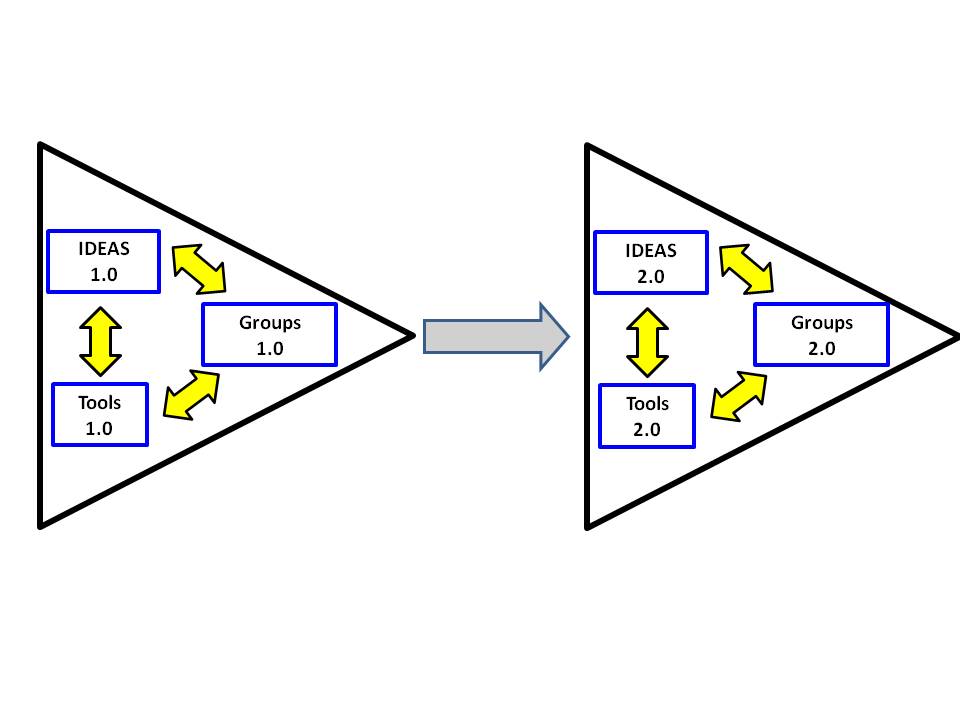

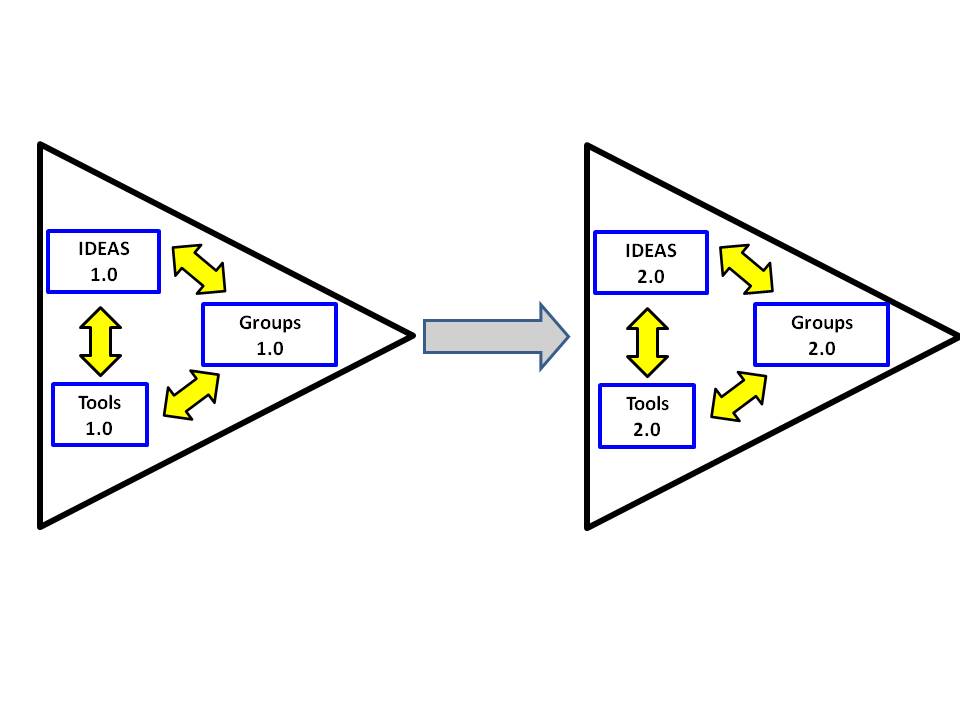

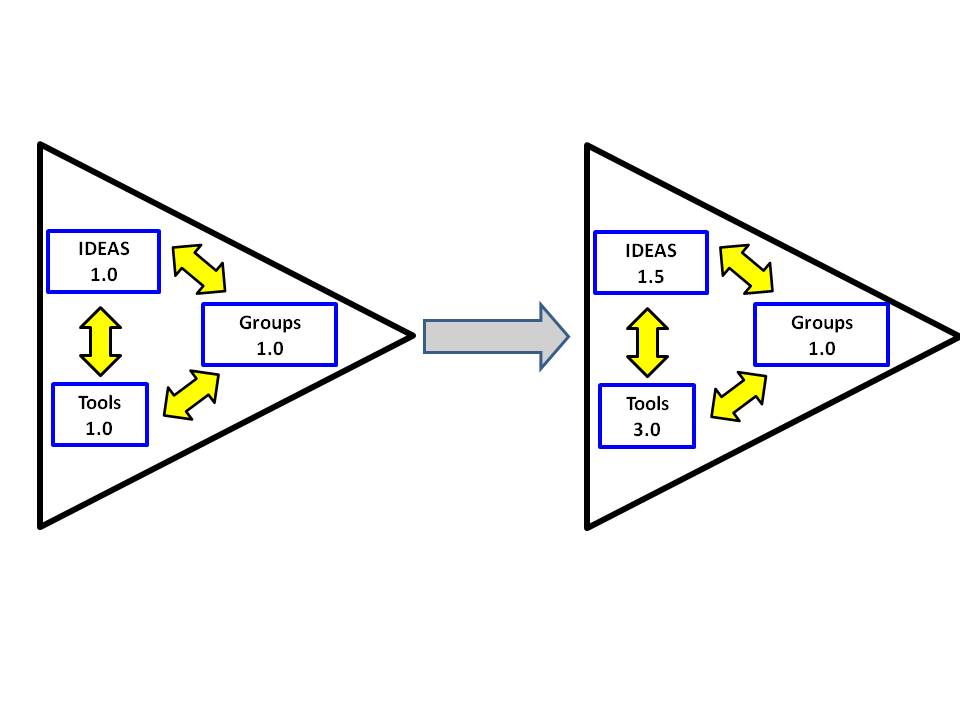

Figure 1. A General Model of Change and Innovation

Successful Innovation springs from the mutual evolution of ideas, groups, and tools, with each influencing the adaptation of the others in no particular order or precedence, but rather by building upon each other iteratively and simultaneously. Let’s look at each component in detail:

IDEAS – Ideas are both the reason groups are formed, and are the genesis of our tools. If the nature of warfare is constant, as most modern strategists advocate, it is because the basic ideas inherent to human nature (including many tacit ones) have stayed constant over the millennia. Ideas set the context for what we do with our tools, and drives the formation and modification of our groups.

TOOLS – Even as the nature of war stays constant, its character is constantly changing mostly due to advances in these. Tools are born from ideas, but they also make new ideas and group social structures possible.

GROUPS – Groups define how we blend both ideas and tools in order to cooperate and adapt to the environment collectively. The way groups are structured through norms, rules, and bureaucracy determines how easily some ideas and tools develop and flourish, and can alternately decide which ones attenuate or disappear. Groups effectively act as the “throttles” of human societal evolution through the predictability and synergy that they make possible by focusing the efforts of many individuals towards common purposes. They also provoke conflict when the identities and aspirations of separate groups come in conflict with one another in ways that cannot be reconciled through compromise or toleration.

Engineering Innovation – How Strategic Agility is Created

We create strategic agility when we actively invest in improvements in all three of the areas mentioned above, and look for new possibilities in each specific area that will help us to release the full potential of the others. We also achieve agility by exploring multiple alternatives in each area, creating the adaptive variety needed to respond to emerging challenges that we won’t be able to fully anticipate. Then when the future presents itself, we have invested in the ideas, groups, and tools we need to cope. To innovate successfully, you have to innovate in all three areas, not just the most familiar or tangible ones.

But there’s a catch…

What we imagine happens – We like to think that there’s a smooth interchange between innovations in the three areas, that Moore’s law will grant us continuous returns in speed and power, that progress will continue upwards on a steady slope, and that the exchange between the three areas will keep pace with each other.

What really happens – In truth, we often see advances in one area without a commensurate advance in the others, creating imbalances that often lead to unpredictable and undesirable results. In many ways we’ve designed “Tools 3.0”, but are still stuck with the old ways of thinking, and the old bureaucratic structures.

We will talk about how and why this happens this week on DEF and the Bridge, and what we can do to maintain a healthy balance between innovations in all three areas.

Conclusion

Innovation is optional, but change is not. As Williamson Murray admonishes us in Adaptation in War (With Fear of Change):

It is clear that we live in an era of increasingly rapid technological change. The historical lesson is equally clear: US military forces are going to have to place increasing emphasis on realistic innovation in peacetime and swift adaptation in combat. This will require leaders who understand war and its reality as well as the implications of technological change. Imagination and intellectual qualities will be as important as the specific technical and tactical details of war making. The great challenge here is how to inculcate those qualities widely in the officer corps.

We’ll use our examination of the three components of the innovation model to help determine what those qualities are, and how we can promote them within our own organizations, even as junior members in the corporate process.

Bottom line: Those who fail to innovate will be left in the dust kicked up by those who do. It’s our duty to be successful innovators – and advocates for the constructs and concepts that lead to successful innovation in groups – lest we forfeit the legacy of freedom and self-determination that those who came before us fought, bled, and died for. You can’t just choose your favorite part of the model and expect that your problems will be solved – if you’re not innovating in all three areas simultaneously, you’re setting yourself up for even more unpredictability, unanticipated systemic consequences and vulnerabilities, expensive projects with little return on investment, and an increased possibility of a catastrophic failure in some situations.

Next in the series: We’ll continue with a deep dive into each component of the model, starting with Ideas.