This article originally featured on the Jamestown Foundation’s China Watch. You can view it in its original format here.

Earlier this month, Caixin reported on another round of Chinese military promotions, highlighting the youth and operational experience of the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) newly minted generals (Caixin, August 12). Moreover, in roughly two years, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will hold its 19th Party Congress, a critical time to enact important military and civilian leadership changes. One change that is all but certain to occur as the PLA continues to promote a new generation of leaders is the appointment of a new PLA Navy (PLAN) commander. While rumors swirled in the Hong Kong press before the 18th Party Congress in 2012 that long-tenured PLAN Commander Admiral Wu Shengli might retire or be appointed Defense Minister, neither of those scenarios occurred (China Leadership Monitor [CLM], January 14, 2013). Instead, Admiral Wu remained PLAN Commander, becoming the oldest member of the Central Military Commission and one of the longest tenured commanders in China’s naval history. [1]

With no more than two years left before his likely retirement, it seems appropriate to begin looking back on the career of one of the PLAN’s most influential and successful commanders. This article attempts to begin that process. The challenges Wu faced and overcame in his early career provide insights into his leadership as PLAN commander. Additionally, Wu’s career has spanned the largest and fastest buildup in the PLAN’s history. Examining the Chinese Navy’s greatest accomplishments under his tenure may therefore help point toward future directions the PLAN could take under the possible candidates to succeed him in the post-Wu era.

A Product of China’s Revolutions

Admiral Wu’s early life and military career reflects some of the most tumultuous periods in modern Chinese history–the war of resistance against the Japanese, the Chinese civil war and establishment of the People’s Republic, and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Born in August 1945, Wu was raised in Zhejiang Province as a well-known “princeling” (太子)–the son of the famous Wu Xian, a Red Army political commissar during the Anti-Japanese war and the Chinese Civil War. Indeed, Wu is purported to have been given the name shengli (“victory” 胜利) in commemoration of the victory over Japan (Office of Naval Intelligence, 2015). After the wars, the elder Wu held important political positions, to include mayor of Hangzhou and vice governor of Zhejiang. Although Wu was raised by his father in Zhejiang, his family’s ancestral home is in Wuqiao County, Hebei Province, about 200 miles south of Beijing. [2]

Wu joined the PLA in August 1964, and began studying at the PLA Surveying and Mapping College in Xi’an, earning a degree in oceanography in 1968 (Guoqing, February 1, 2012). His timing was fortuitous, as his affiliation with the PLA likely helped shield him as the Cultural Revolution decimated Chinese social, government and Party institutions in what amounted to a low-intensity civil war. Over 12 million of Wu’s generation, including current senior PLAN officers, were forced to work on rural communes as part of China’s “sent down youth” movement. [3] As a member of one of the only institutions left standing, however, Wu was saved from this fate by joining the PLA. However, given what we know about the Cultural Revolution’s impact on the nation’s academic institutions, the quality of training he received in Xi’an was highly questionable, and Wu would not receive formal training again until 1972, when he attended the captain’s course at the Dalian Naval Vessel Academy. [4]

After Xi’an, Wu’s early career was spent gaining experience as a surface warfare officer in the East and South Sea Fleets in the 1970s and 1980s, serving as both commander of the East Sea Fleet’s (ESF) 6th Destroyer Flotilla and as deputy chief of staff for the Shanghai Naval Base. The fact that future President Jiang Zemin was serving as Shanghai Party secretary at this time has led some PLA-watchers to speculate that Wu may have cultivated ties with Jiang. [5]

Yet Wu and his colleagues lacked combat experience. The closest that Wu is known to have come to combat was as the commander of the ESF’s 6th Destroyer Flotilla, when he had authority over the FrigateYingtan (CNS 531), one of the vessels which took part in the 1988 Johnson South Reef skirmish with Vietnam. [6]

In 1992, Wu became chief of staff of the ESF’s Fujian Support Base. This was soon followed by an appointment as commandant of the Dalian Naval Vessel Academy, a highly influential post, which allowed him to affect the direction of training for future PLAN officers. Wu returned to the ESF as a deputy commander in 1998. He was appointed South Sea Fleet (SSF) commander in 2002, and promoted to vice admiral in 2003. In 2004, he became one of the few naval officers to serve as a deputy chief of the PLA General Staff, a position equivalent to a commander of one of China’s seven Military Regions and the second-highest-ranking operational officer in the PLA Navy (Center for China Studies [Taiwan], June 5).

Shepherding the PLAN’s Transition

Wu’s background, family connections and professional experiences made him a strong candidate for top leadership roles. Thus, when cancer forced Admiral Zhang Dingfa into retirement in 2006, Wu was promoted to PLAN Commander just as the navy was on the cusp of an organizational transformation. In 2004, Hu Jintao gave his landmark address on the PLA’s “New Historic Missions,” which declared that China’s interests abroad were expanding, and that the PLA had an important role to play in defending those interests (Xinhua, June 19, 2006).

This new direction provided the PLAN with a substantially increased role in the implementation of China’s national security and military engagement policy. For Admiral Wu and his contemporaries, this challenge was exacerbated by years of isolation from the international naval community, which, along with the domestic effects of the Cultural Revolution, led to a dramatic erosion of professional and technical skills, as well as a severe decline in human capital and basic quality of life within China’s navy. [7] Indeed, Admiral Wu seems to have personally taken an interest in improving the quality of life of China’s sailors. Wu’s writings include details about the difficult and backwards conditions onboard PLAN ships earlier in his career, noting how PLAN sailors routinely “would go into port but not go ashore, eat while squatting on deck, hold meetings on folding stools and sleep on metal siding.” [8]

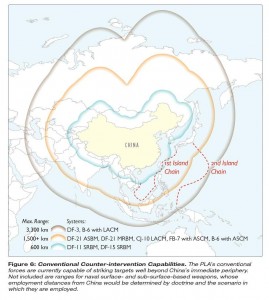

This makes Admiral Wu’s success in overseeing the PLAN’s transformation all the more compelling. While he and members of his cohort were responsible for overseeing a rapidly transforming navy, complete with formally trained officer candidates, they themselves had only limited formal training. Though tasked with preparing the PLAN to conduct blue water operations, the navy Wu Shengli had joined was still overwhelmingly a coastal defense force. Despite these challenges, within a few years of assuming command, the PLAN would be conducting anti-piracy escort operations in the Gulf of Aden, evacuating Chinese citizens far from China’s borders, (first in Libya in 2011 and later in Yeman in 2015), and participating in progressively more complex multinational maritime exercises, including the U.S.-led Rim of the Pacific exercise in 2014 (RIMPAC-14) (China Brief, April 3; China Brief, May 1; Also see “Six Years at Sea… And Counting”).

Viewed in this context, what Wu and his contemporaries have accomplished in transforming the PLAN has been even more remarkable. The PLAN Commander and his staff must have truly been followed Deng Xiaoping’s aphorism to “cross the river by feeling the stones,” in part learning as they went about modernizing the PLAN and partly relying on younger, more technically trained PLAN officers–individuals who constitute the next generation of PLAN leadership. The history of China’s naval transformation in the 2000s has yet to be written, but understanding how Admiral Wu and his advisors managed this will be fascinating reading when the details come to light.

Improving USN-PLAN Relations

Navies often play the lead role in a country’s foreign military relations, and after having spent almost a decade developing the personnel relationships and diplomatic acumen that facilitates international engagement, Admiral Wu has in many ways become the face of the PLA abroad. Nowhere is this influence more apparent than in the PLAN’s growing engagement with the United States Navy (USN). Throughout this time, Admiral Wu has been a constant presence, meeting with each of the past three U.S. Navy Chief of Naval Operations (CNO). In 2014 alone, CNO Greenert met with Wu on four separate occasions, the most of any foreign navy leader (USN, September 8, 2014).

Like any PLA officer with whom the U.S. Navy interacts, Admiral Wu’s talking points have been carefully selected and vetted by the Party. His statements in official settings reflect what the Party views as primary objectives for the military-to-military exchange. However, Wu’s long years of experience appears to have helped create a degree of stability in the U.S.-China navy-to-navy relationship not seen in the past. The two navies have worked together in multiple settings, including in the Gulf of Aden and in Hawaii at RIMPAC-14. They have conducted reciprocal port visits in Zhanjiang, San Diego and Hawaii, established the Code of Conduct for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES) through cooperation in the Western Pacific Navy Symposium (WPNS) and continue to move forward on additional confidence building measures (Xinhuanet, April 23, 2014; Xinhuanet, December 14, 2014).

At the same time that the PLAN appears to have pushed its relationship with the U.S. Navy to new heights, the PLAN continues to play a vital role asserting China’s interests closer to home. For Admiral Wu, this ability to do both simultaneously reflects an adept and skillful use of maritime diplomacy. As China continues this assertive behavior however, this skillful balancing act may become increasingly difficult to maintain. Moreover, as Wu Shengli moves closer to retirement, his experience in helping manage this tension will surely be missed.

The Chinese Navy in the Post-Wu Era

While PLA decision making has become more transparent, opaque factors, including personal connections, family relationships and ever present corruption, make predicting who Wu’s successor will be impossible. That however, has never stopped China analysts from putting forth possible candidates for future promotion. With that in mind, the following three officers have been discussed at length as possible candidates to replace Admiral Wu:

Admiral Sun Jianguo: As the PLA’s deputy chief of staff in charge of intelligence, Admiral Sun is the second highest-ranking operational officer in the PLA, a position that Admiral Wu once held before becoming PLAN Commander. [9] Unlike Wu, Admiral Sun’s experience has largely been as a submariner, and he has captained both conventional and nuclear submarines, including those involved in espionage missions in the Taiwan Strait. [10] However, as a contemporary of Wu’s (Sun was born in 1952 and joined the PLA in 1968), he would be 65 by the 19th Party Congress, and thus would likely serve only an abbreviated tenure as PLAN commander.

Vice-Admiral Tian Zhong: A less likely but interesting alternative choice is Tian Zhong, who earlier this year was transferred from his former position as North Sea Fleet commander to deputy PLAN Commander, a position that provides him a seat on the PLAN Party Standing Committee. Relatively young at 59, Tian’s has moved through the ranks at a rapid pace. In 2007, he was promoted to NSF Commander after serving only a year as NSF chief of staff (Center for China Studies, August 3). Perhaps more tellingly, Tian was the youngest and lowest-ranking PLAN officer to serve on the CCP Party Central Committee. While still a fleet commander, Tian served on this elite organization alongside PLAN Commander Wu Shengli, PLAN Political Commissar Liu Xiaojiang and Admiral Sun Jianguo (Xinhua, November 14, 2012).

Vice-Admiral Jiang Weilie: Like Tian Zhong, former SSF commander, Jiang Weilie also became a PLAN commander in 2015. Jiang appears to be something of a technocrat, having served in the PLAN Equipment Department in 2010. [11] This is a highly unusual career move–few operational officers spend time in technical departments, a separate career track. [12] While in this department, Jiang was tasked with overhauling the PLAN’s equipment acquisition systems, after which he was rewarded with a fleet command. As the PLAN seeks to replace Wu’s international engagement experience, it should be noted that Jiang has also had multiple engagements with his U.S. Navy counterparts, most recently traveling to Hawaii in 2014 to serve as China’s VIP during its first-ever participation in RIMPAC-14 (Phoenix Online, July 22, 2014).

Conclusion

Whoever is selected as Admiral Wu’s replacement will be taking charge of a dramatically different force than the one Wu Shengli took command of in 2006. Thanks in part to his leadership, China’s navy today is far more capable, active and engaged with the rest of the world. It is staffed by more professional and formally trained personnel than at any time in China’s recent history, and enjoys a stable and robust working relationship with the USN and other international navies in large part due to his years of experience in maritime diplomacy and careful cultivation of relationships.

Notes

1. Although former PLAN Commander Xiao Jingguan nominally served as PLAN Commander for almost 30 years from 1950 to 1979, he was effectively sidelined during much of this time as a result of factual political infighting during the Cultural Revolution.

2. Jeffrey Becker et al., Behind the Periscope: Leadership in China’s Navy (Alexandria, VA: The CNA Corporation, 2013), p. 136

3. This includes for example current North Sea Fleet Commander Admiral Yuan Yubai. Before joining the PLAN in 1976, Admiral Yuan spent two years as a full-time member of his “Basic Line Education Work Team,” in Gongan County, Hubei Province. “Work Teams” were ad-hoc organizations invested with local authority during the Cultural Revolution. Jeffrey Becker et al., Behind the Periscope: Leadership in China’s Navy, p.183.

4. Cheng Li, “Wu Shengli – China’s Top Future Leaders to Watch,” Brookings, accessed March 18, 2015.

5. Ibid.

6. Yang Zhongmei, China’s Coming War: The Rise of China’s New Militarism (中國即將開戰: 中國新軍國主義崛起) (Taipei: Time Culture Press, 2013), p. 210–211

7. Admiral Liu Huaqing’s biography provides some exceptionally painful examples of just how far the PLAN had fallen immediately following the Cultural Revolution. See Liu Huaqing, Memoirs of Liu Huaqing, (刘华请回忆录), (Beijing: PLA Press, 2004), pp. 417-432.

8. Wu Shengli, “Beginning to Bid Farewell to Sleeping and Eating Aboard the Ship in Port: The Lifestyle Revolution for Chinese Sailors,” PLA Life (Jiefangjun Shenghuo; 解放军生活), no. 9 (2010).

9. Jeffrey Becker et al., Behind the Periscope: Leadership in China’s Navy, p. 173.

10. Shih Min, “Hu Jintao Actively Props up ’Princeling Army,” Chien Shao, April 1, 2006, no. 182.

11. Ma Haoliang, “High-Ranking Officer Adjustments in the Navy with a Focus on Having a Technologically Strong Military (海軍將領調整 凸顯科技強軍),” Ta Kung Pao, February 9, 2011

12. Kenneth Allen and Morgan Clemens, The Recruitment, Education, and Training of PLA Navy Personnel(China Maritime Studies Institute, 2014).