By W. Alejandro Sanchez

Argentina has requested that the United Kingdom engage in diplomatic talks regarding control of the Falkland Islands, or Islas Malvinas, depending on which side you support. As the islands will not change hands anytime soon, with London citing a 2013 referendum as proof of the Falklanders’ desire to remain in the UK, the dispute will continue. Nevertheless, in spite of occasional aggressive statements or alarmist media reports from either London or Buenos Aires, it is important to highlight that neither side has significantly increased their defense spending vis-à-vis the islands.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

The War

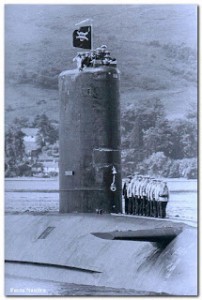

In 1982, Argentina launched an invasion of the islands, as the military government in Buenos Aires wanted to distract the Argentine population from the country’s crumbling economy and unite the citizenry behind the junta. The Falklands War has been extensively analyzed (see such essays as “Delayed Reaction: UK Maritime Expeditionary Capabilities and the Lessons of the Falklands Conflict,” and “Facts Influencing the Defeat of the Argentine Air Power in the Falklands War”) but a word must still be said about the conflict. The war is significant because, as Dr. Ian Speller explains, it “was the first time since 1945 that a major western navy had come under sustained air attack at sea [and] it was the first time that a nuclear-powered hunter killer submarine conducted a successful attack on enemy surface units.”

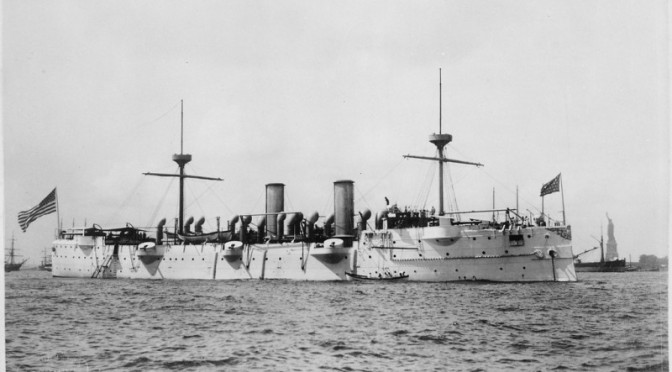

The navies and air forces from both sides were actively engaged in the battle to control the Falklands. As for successful attacks, aircraft from the Argentine Air Force and Navy managed to sink British vessels like the warships HMS Sheffield and HMS Ardent, and the supply ship MV Atlantic Conveyor, among others. Meanwhile, a British nuclear submarine, the HMS Conqueror, sank the Argentine Navy’s flagship, the ARA General Belgrano.

Official Statements

To this day, Argentina continues to claim ownership of the islands. Case in point, now former-President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, declared this past April that she foresaw that one day the islands would be under Argentine control. A month earlier, UK Defence Secretary Michael Fallon announced that “we are going to beef up the defence of Falkland Islands,” the obvious assumption being that the islands need protection from a possible Argentine attack. These statements come to no surprise, as over the past years Buenos Aires and London claim that the “other side” is taking aggressive steps regarding the islands.

The islands, particularly after the war, are a key part of Argentine nationalism, hence it should not be surprising that Argentina’s new head of state, President Mauricio Macri, will give the occasional nationalistic statement over the islands or call for negotiations. Nevertheless he also wants U.S. and European investment to jump start the country’s economy, so he may not be overly aggressive (after his electoral victory in November, Macri and Prime Minister David Cameron held a telephone discussion in which they agreed on forging closer commercial ties). I would argue that nationalistic statements or calls for dialogue with London from Buenos Aires are mostly for internal consumption, as a way for President Macri to show his people that he has not forgotten about the islands. After all, it would be political suicide for any Argentine president to not make the occasional patriotic declaration regarding the Falklands.

Defense Realities

Provocative calls for negotiations aside, the Argentine Navy is in no particular shape to engage in a new conflict over the islands. The Navy’s biggest acquisition in recent years was that of four Russian multipurpose ships (Aviso/Neftegaz-class), which will be utilized for search and rescue operations and scientific projects around the Antarctic. The vessels arrived to the South American nation this past December. Theoretically, the Navy could install weapons systems aboard the vessels, but it is unlikely that this will happen due to budgetary

limitations. Regarding submarines the only new development is that in 2014 the ARA San Juan (a diesel TR-1700-class) was finally returned to the Navy after it underwent repairs that had taken several years to complete.

As for the Air Force, which was a critical factor in Argentina’s victories at sea during the Falklands War, just this past November it decommissioned its aging Mirage warplane fleet. The problem is that the Air Force does not have a new warplane to replace the Mirage. Over the past years there were rumors that Buenos Aires would acquire Russian Sukhoi warplanes (hence the need for London to “beef up” the defense of the islands) but this deal never materialized. Similarly, a recent deal for Israeli Kfir warplanes has been put on hold. For the time being, Argentina will have to rely on trainers, such as the Pampa III, and various, also aging, aircraft to protect its airspace.

The Air Force’s situation is so dismal that during the December 2015 inauguration ceremony of President Macri, Argentina requested that Uruguay have three of its own Cessna Dragonfly planes on alert, ready to support Buenos Aires if some crisis occurred. While this request speaks well of Argentina-Uruguay defense relations, it highlights that the Argentine military is hardly in any shape to attempt a renewed operation to take over the Falklands.

As for the UK Navy, the big news is that it is constructing two new carriers, one of which, the HMS Queen Elizabeth, should be operational by 2020. The new vessels are part of a push for greater defense spending by London. Just this past December, Secretary Fallon declared that “we have said we will maintain a minimum fleet of 19 destroyers and frigates, but as the older frigates are retired we also hope to add a lighter frigate between the offshore patrol vessel and Type 26 and to build more of those as well.” Additionally, the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy will benefit from having the new F-35 warplanes in their inventory, as “the Lightning II will be the backbone of Britain’s future carrier operations.” (Of course, how long it will take for the F-35 to be delivered is another question).

Regarding the Falklands themselves, the Royal Navy maintains the HMS Clyde stationed there as part of its South Atlantic Patrol program (in November 2015, the HMS Clyde assisted in rescuing tourists trapped in a sinking cruise ship close to the Falklands). Additionally, the British daily Express reported that this past April British troops carried out exercises in the Falklands which simulated an invasion of the islands. As for new equipment, the only major ongoing acquisition program seems to be additional Giraffe AMB radars, manufactured by Saab.

One could argue that the British military is suffering from exhaustion due to the multiple operations it carries out around the world, from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to security operations in the Mediterranean and the Horn of Africa. Just this past December, the destroyer HMS Defender was deployed to the Mediterranean to support the French carrier Charles de Gaulle. Given its multiple ongoing operations, it’s difficult to say how long it would take London to organize a new expeditionary force that would be sent to the Falklands, should another conflict occur. (Daniel Gibran’s The Falklands War, 1998, provides a great summary of the logistical success of deploying over 50 warships, over 50 support vessels, aircraft, troops, ammo and other supplies to the South Atlantic – p. 80-83).

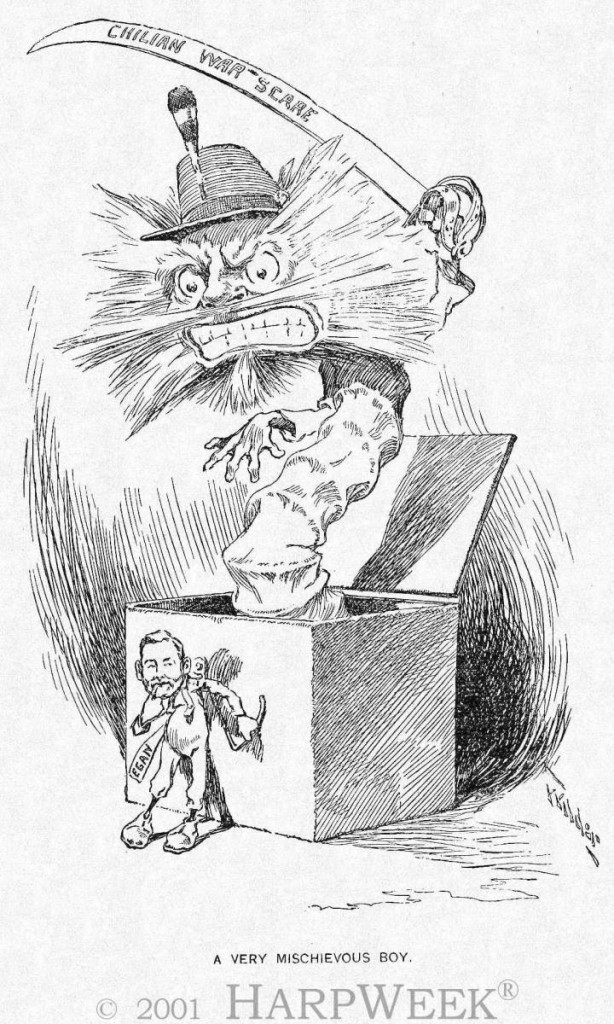

Conspiracy Theories/Exaggerations

Finally, a word must be said about accusations originating in both London and Buenos Aires concerning the other’s intentions regarding the Falklands. As previously mentioned, while there has not been another war over the islands since the early 1980s, just about every year there are accusations that either the Argentine or British government are behaving in an aggressive manner. For example, in 2012 Argentina accused the UK of “militarizing” the South Atlantic. Moreover, the Argentine media widely reproduced the March 2015 comments by Secretary Fallon about “beefing up” of the defenses in the Falklands. In particular the Argentine media quoted and discussed a March 23, 2015, report by the British tabloid The Sun that London feared an imminent attack by Argentina, with Russian support. At the time, the ongoing theory in the British media was that, due to the close relations between Moscow and Buenos Aires (largely due to the friendship between President Vladimir Putin with then-President Kirchner), Russia would somehow support Argentina’s military in the islands.

Final Thoughts

As a reminder, Argentina did not purchase the Russian or Israeli planes while, apart from one military exercise and new radars, the British have yet to significantly beef up their security of the islands. Thus, I would argue that currently the possibility of a renewed war remains extremely low, particularly now that the new Argentine President Macri is actually trying to approach the West (meaning the U.S. and Europe) for investment in order to improve the country’s economy. The British government seems to have a similar assessment of the situation as the Strategic Defense and Security Review 2015 explains that “we judge the risk of a military attack [against the Falklands] to be low, but we will retain a deterrence posture, with sufficient military forces in the region, including Royal Navy warships, Army units and RAF Typhoon aircraft.”

The information presented in this analysis argues that in spite of the occasional alarmist report, neither side has actually carried out major military-related initiatives that could be labeled as aggressive. Argentina has not acquired significant military equipment aside from four Russian research vessels and its repaired old submarine, while the UK, apart from one military exercise, does not seem to have sent additional troops or vessels to the islands. While diplomatic tensions will remain for the immediate future, as Buenos Aires will not give up its claim to the islands and London will not negotiate their fate, hopefully we will not witness another war over the Falklands. Then again, as Gibran states “predicting state behavior is not an exact science, especially in conflict situations. The assumption of a rational behavior on the part of a country, however desirable this idea may appear, is not a given state of affairs” (The Falklands War, p. 89).

As a corollary to this analysis, in early January the oil and gas company Rockhopper announced that it had discovered oil in its Isobel Deep well in the Falklands. The potential of big oil reserves is another reason for Argentina’s claim on the islands, and the recent discovery will give new impetus for calling for negotiations. If nothing else, we can be thankful that both militaries, particularly their navies, are hardly in a position to participate in another war just yet.

W. Alejandro Sanchez is a researcher who focuses on geopolitics, military and cyber security issues in the Western Hemisphere. His research interests include inter-state tensions, narco-insurgent movements and drug cartels, arms sales, the development of Latin American military industries, UN peacekeeping operations, as well as the rising use of drones in Latin America. The views presented in this essay are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any institutions with which the author is associated. Follow him on Twitter @W_Alex_Sanchez

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

![9 July 2015 Seizure of Narco Submarine U.S. Coast Guard Image from Video [FOR PUBLIC RELEASE] U.S. Agencies Stop Semi-Submersible, Seize 12,000 Pounds of Cocaine 94th Airlift Wing, U.S. Coast Guard Pacific Area. DVIDS/DMA, 19 July 2015.](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/sub2.jpg)