A Modest Proposal to Help this Generation’s “Boat People”

By John T. Kuehn

First, this article may be too late. What do I mean? I mean that we—as in the global community and the United States in particular—may be too far behind the power curve to do something meaningful about helping the refugees fleeing across the sea from the Syrian Civil War-Islamic Thirty Year’s War raging in the Middle East. This is my way of saying I wish I had written this about six months ago when the problem was manifest to all. So why write at all? Something might be STILL done with forward deployed naval forces of the United States today, perhaps with like-minded maritime allies to help the unfortunate masses of humanity fleeing their homelands from a particularly cruel conflict. Even if it is too late for current policy, the trend of “boat people” fleeing war to a better life elsewhere has many precedents in history, especially the last one hundred years and it will most certainly occur again. This means that ringing the clarion now might contribute to effective humanitarian policy action in the future. So it is worth a try.

First, let us briefly review some relevant history on these sorts of refugee crises as they pertain to migration in unseaworthy craft in search of a better life on distant shores. Case one takes us back to 1975 and the late 1970s when the United States’ lost war in Vietnam resulted in the flight of the boat people of South Vietnam (and Cambodia, too) from the proletarian utopias established by the new Vietnamese government in Hanoi and the Khmer Rouge. The United States was caught napping somewhat on this one, too, but before long had started making efforts with naval assets based in the Western Pacific to help with this crisis. However, years later a particularly unfortunate incident occurred in the 1980s wherein the captain of a U.S. warship (the USS Dubuque) failed to render proper assistance to fleeing “boat people” who later survived to present evidence against him. We will return to this issue since it is a feature of the law of the sea that mariners must render aid to people in danger on the high seas. More recently Americans saw the flight of people from both Cuba and Haiti to the United States in the 1990s, fleeing various natural and man-made disasters in the Caribbean.

Why should the United States use its assets, especially its Navy, to help these people? There are three principle reasons: moral obligation, humanitarian, and practical. The practical value for the United States involves two factors, leadership and what, for lack of a better term, might be called “good press.” If the U.S. is to be a leader it must take the lead in areas where it claims an interest. By getting more involved and working with other states of the region while at the same time committing actual naval forces to help, we build partnerships, lead, and help. It is a win-win-win result.

From a moral standpoint we owe it to these people. Here is the causal logic—when the U.S.-led coalition invaded Iraq all those years ago we removed the government in power and destabilized the region. From that context Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) developed. During the final years in Iraq we estimated we had pretty much solved the problem of AQI, but instead it had simply transformed itself into the current Islamic State (ISIS). At the same time Syria fell into civil war, a conflict not unrelated to our actions in Iraq and has been further de-stabilized, especially since 2013, by an increasingly powerful and dangerous ISIS. The upshot is that some, not all, of these refugees can be traced to American policy choices, so there exists something of a moral obligation to help with the result of our, for lack of a better word, blundering in the Middle East.

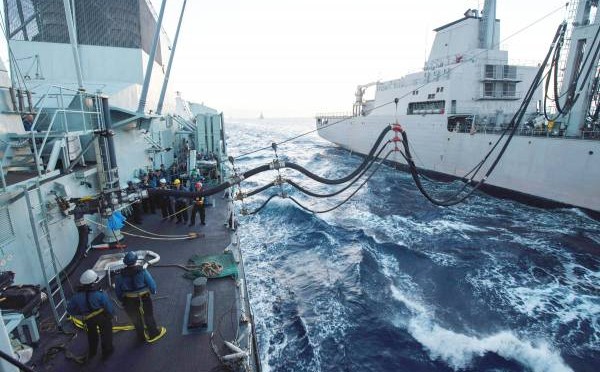

Finally, we get back to the purely humanitarian reasons—the salvation of (mostly) innocent human life. Obviously things are being done, but there is little reason to allow people to helplessly drown or die of exposure at sea on un-seaworthy craft. They already think they can make it and so the arguments that they would not flee if they did not think someone would help are not only ill-informed, they are morally wrongheaded. In fact, the United States by simply having ships in the Eastern Mediterranean is obligated to “render assistance” should it run across people in distress on the high seas. Simply stationing ships on patrol in that area will naturally result in a requirement to render assistance because we certainly do not want any more Dubuques like we had in the South China Sea after the Vietnam War had ended.

As with any use of American taxpayer-funded projects, use of U.S. Navy assets must be judicious. Also, we must coordinate with partners and allies in the region, but rendering assistance on the high seas is part of international law and a moral imperative, more than one might think given our distance from the Eastern Mediterranean. However, if the United States is to use its Navy as the “sysadmin” of the global maritime regime, as Captain Peter Haynes discusses in his recent book on the “new maritime strategy,” then this sort of action and use of naval power is part of the responsibility that the mantle of maritime leadership confers. Or perhaps we no longer aspire to lead in this domain? I think not.

Dr. John T. Kuehn is the General William Stofft Chair for Historical Research at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College CGSC). He retired from the U.S. Navy 2004 at the rank of commander after 23 years of service as a naval flight officer flying both land-based and carrier-based aircraft. He has taught a variety of subjects, including military history, at CGSC since 2000. He authored Agents of Innovation (2008), A Military History of Japan: From the Age of the Samurai to the 21st Century (2014), and co-authored Eyewitness Pacific Theater (2008) with D.M. Giangreco as well as numerous articles and editorials and was awarded a Moncado Prize from the Society for Military History in 2011. His latest book, due out from Praeger just in time for the 200th Anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo is Napoleonic Warfare: The Operational Art of the Great Campaigns.

The views are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.