By Sally DeBoer

As a part of CIMSEC’s South China Sea topic week and our regular Sea Control Podcast, we bring you a discussion on the UN’s Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling on territorial disputes in the South China Sea with one of the China-watching community’s best known, most respected, and outspoken voices, retired U.S. Navy Captain James Fanell. Captain Fanell and host Sally DeBoer discuss the implications of the ruling, thoughts on Chinese, American, and international reactions to the court’s findings, and possible directions for the U.S. and its allies in the Asia-Pacific going forward. A transcript of the discussion can be found below, as well as a download link of the audio recording. This interview has been edited for clarity.

DOWNLOAD: The PCA Ruling with CAPT James Fanell

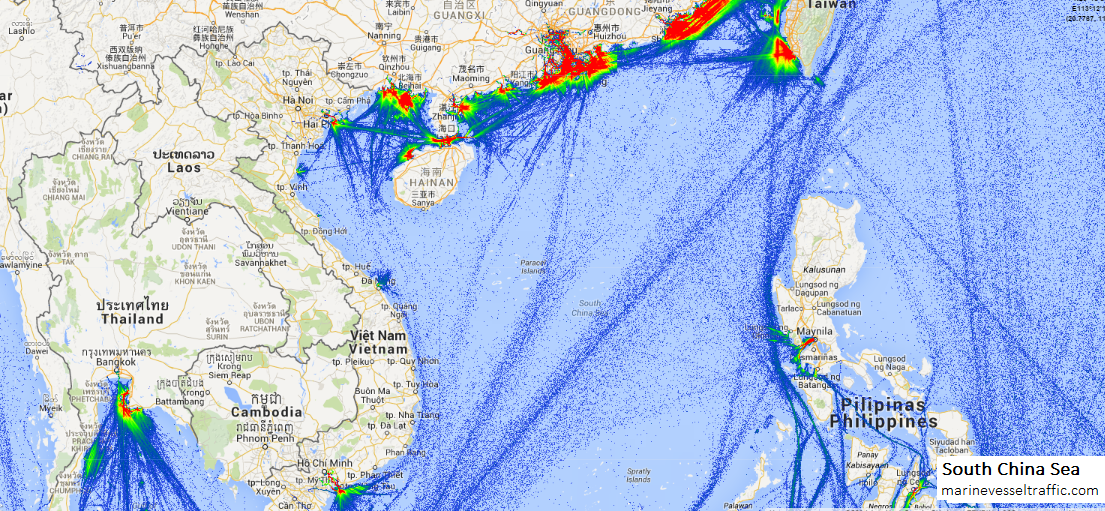

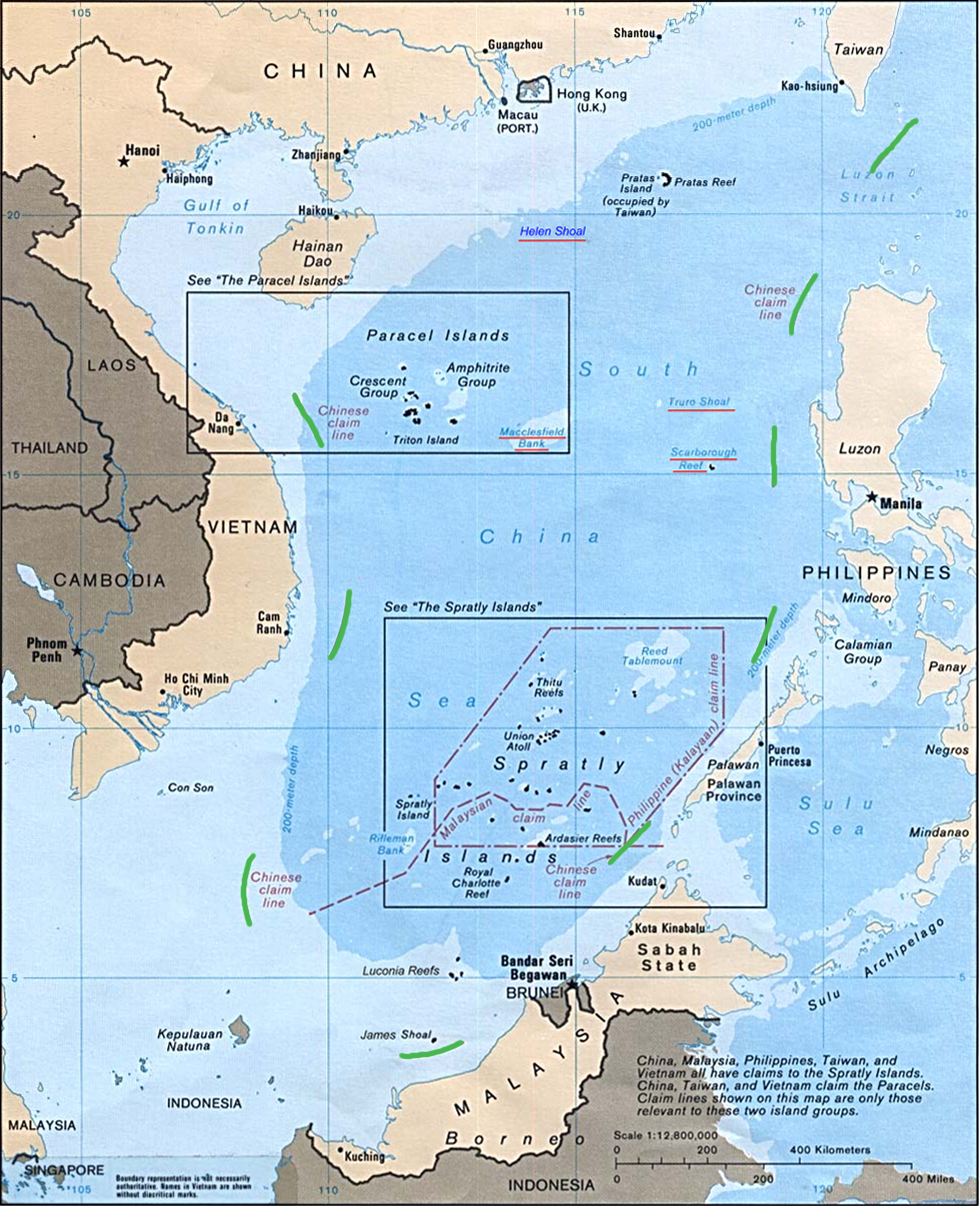

SD: On July 12th, the UN’s Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled on territorial disputes between the PRC and the Philippines in the South China Sea (SCS). The court ruled largely on the side of the Philippines, denying the legitimacy of China’s claims and upholding international law as outlined by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, recognizing territorial seas, but not exclusive economic zones, of several disputed features, including the Spratly Islands. Further, the court found that China violated the Philippines’ sovereignty when they interfered with fishing and petroleum exploration activities in the Philippines exclusive economic zone. The court also upheld the right of both China and the Philippines to conduct fishing in and around Scarborough Shoal. China, who has denied and continues to deny the legitimacy of the court’s ruling, publicly stated its intention to both ignore the court’s findings and continue construction of artificial islands. Immediate responses from Chinese media stated that the ruling was an “American-backed farce,” while statements from Chinese officials echo this sentiment and reinforce their commitment to exercising control over their “nine dash line” claims. Clearly there is a great deal to unpack and discuss on this ruling and its implications going forward. Fortunately for us, our guest today is an expert on the matter. Joining us today is retired U.S. Navy Captain James Fanell, former Director of Intelligence and Information Operations for the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet, and founder of Red Star Rising. In the tradition of our Sea Control podcast, we will give Captain Fanell a chance to introduce himself before we get started.

JF: Good Afternoon, Sally, thanks for inviting me to participate in Sea Control and CIMSEC’s valuable efforts to bring information to the general public and raise our consciousness on what’s going on in the maritime domain. I’m pleased to talk about this subject and there’s a lot to cover and I will just say that I am happy to be talking to you from Eastern Switzerland where I’m currently a fellow at the Geneva Center for Security Policy.

SD: I want to begin by characterizing the ruling. Sir, what was your general impression of the courts’ finding? Is the finding more or less sweeping than you had expected – are there any facets of the ruling that surprised you?

JF: The ruling itself is a resounding repudiation of China’s actions, statements, and posture over the last five years in the Asia-Pacific region. The court went much farther than I think anyone predicted in the academic or intelligence communities that I’m associated with. I think the court surprised many people by pointing out the things you described in your opening, which is to say they ruled on whether or not a feature is entitled to an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) or a territorial sea. [The ruling] raised the bar on what constitutes an island with respect to Itu Aba. Previously, many had thought that the requirements, based on a general reading of UNCLOS, would suggest that if [a party] could provide habitability from a land feature to include it’s own water sources, that would somehow guarantee an EEZ. The Court raised that bar and said, no, it has to be more than just water to be life sustaining, it has to demonstrate habitability and the ability to sustain life – in that case the court looked back and said there was nothing on Itu Aba that would suggest that. That’s caused a bit of a development between Taiwan and China.

But besides that one point, I think the larger issue is that there was nothing here for China. They had nothing to hang their hat on, there’s nothing for them to go forward with and from that standpoint, it is going to be very difficult for them in terms of saving face. But from an international law perspective and what most of the world accepts – China’s actions in the SCS were unilateral, aggressive, and threatening to their neighbors. This ruling states that this behavior is not correct and that this is not an accepted way to act in the international community.

SD: So definitely a precedent setting ruling then. You talk about China’s ability to save face. Let’s talk about the Chinese response to the issue. It is an understatement to say they have not taken the ruling well. Before we talk about their international response, I would like to briefly discuss China’s internal reaction to the ruling. In 2017, the PRC’s 19th party congress will occur and there is significant potential for change in the Politburo. How much of Xi Jinping’s response to the ruling is for domestic consumption and to maintain credibility and consistency with his domestic audience?

JF: I think that based on the research from Red Star Rising and open-source scouring of Chinese media and press reporting in English and Chinese, what we’re seeing is that China has presented a unified response across the domestic and world audience that says they refuse to accept this. You mentioned that they used the term ‘farce,’ just about every Chinese response to this ruling has used the word farce. The main Chinese press organs all have special web pages devoted to this SCS arbitration…“the farce should end.”

There’s no question that the party has set a pretty strict line on responding to this. The senior leaders of China, [up to and] including President Xi Jinping and Admiral Wu Shengli have said they’re not going to accept this and that China won’t abide by this ruling. What’s more worrisome is that they’ve said that they’re going to – if pushed, if challenged – respond in kind. So I think that’s the great concern for the international community – just how far will China go to disregard this ruling and will they use physical force, physical violence, to maintain their, if you will, physical possession of these disputed areas? They say they won’t do that, they say they are peace loving and they won’t inhibit anyone’s freedom of navigation, but in the same speeches they tell us that they’re going to not accept outside influence from non-parties of the region and that they’re not going to accept having their sovereignty violated. So that’s the concern that people have now.

SD: In your opinion, is this response to serve a larger Chinese narrative that the region is peaceful and that the U.S. is interjecting in affairs where it doesn’t belong?

JF: That’s exactly what they’ve said. They’ve characterized the U.S. as being the offending party. In fact, just today there was an article in one of the press organs that stated that just the presence of the United States is offensive and causes problems. Not just that [the U.S.] does FONOPS, but just [their] very presence has been a destabilizing factor. So the narrative over the last five years from China has changed [from having] said we’re not trying to displace the U.S., to this argument that the US’ very presence is causing the turmoil…they need to get out of here, it’s not China that is the problem. Which is in complete contradiction of what this impartial, unbiased tribunal out of the Hague handed down two weeks ago. As you can imagine, the Chinese press has gone after the Hague’s ruling, first to discredit them by saying they are not part of the UN, and now they’re going after one of the senior members of the tribunal, saying that he is a biased Japanese national and therefore was only implementing the desires of [Japanese] Prime Minister Abe. So their attack on this ruling is across the board and across all facets of conversation and ideological perspectives. They are 100 percent going after this thing, and I think that’s an indicator of what they’re actually going to do in the physical domain in the lead up to the party congress that you mentioned.

SD: This week, the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Richardson visited China and had a discussion with the PLAN’s leader, Admiral Wu Shengli, where he was roundly assured that Chinese construction in the Spratly Islands would “never stop.” What do you make of this directness, and what can the United States do to reinforce the courts’ rulings?

JF: Admiral Richardson’s visit has caused some level of controversy in the U.S. regarding the timing of this visit. He accompanied NSA (national security adviser) Rice to China – and the issue was – what kind of message was he taking and what kind of message did he receive? As you mentioned, the message he received was very clear and unambiguous from Admiral Wu. [He said] we reject the findings of this court, it has no legitimacy, it has no authority, and these are our sovereign territories…it’s been that way since ancient times, and it will be at our place and choosing to declare an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ), it will be in our time and choosing when to place military equipment on these islands, and we will do that in response to the challenges that we get from the Philippines, Japan, or the U.S. So, Admiral Richardson, in many respects, was given a lecture by Admiral Wu.

We can talk about that at another time, but the simplistic answer is that it appears the Chinese were able to spin this visit, which was surely prearranged while knowing the date the ruling would be released, and use that to their advantage to portray to the people of China that the U.S. kowtowing to the leaders of Beijing saying ‘hey, we’re in charge despite any piece of paper…possession is nine tenths of the law and we own and physically control it all.’

What will be interesting to see is what will come out of the dialogue between the CNO and Admiral Wu regarding the specific issue of Scarborough Reef. Admiral Richardson made some statements back in March that China was preparing to build up Scarborough Reef just like it had done in the southern Spratly Islands. The question is whether or not China will use this ruling as justification for going ahead and reclaiming land around Scarborough and building another base, another naval installation…not sure it will be a Naval Air Station as Hainan Island is fairly close. If they do they’ll have control of the northern approaches to the SCS just like they have physical control and possession of the southern approaches to the SCS. This is the concern, and I don’t speak for the CNO, but I feel disappointed and ashamed that he had to take that kind of public treatment when we knew that the Chinese were going to reject the ruling in the first place.

SD: So they’re sending an unambiguous message in terms of their statement, but they’re also sending a physical message. Earlier this week there was the H-6K over flight of Scarborough Shoal. What do you make of that, and what do you make of the exercises around Hainan Island that were likely planned before this ruling, where China announced they would be “closing off” a part of the SCS which is not in line with any legal precedent.

JF: Some Chinese experts commented in the press that this is the first time that we’ve publicly provided these pictures [of the bomber overflight]. Some were implying that this was the first time an H-6K had directly overflown Scarborough Reef, some made the point that the plane was vectored and pointing toward Manila, implying that it could be used to do more damage than maybe some would consider. In that same vein, some mentioned Chinese planes can now reach everywhere in the SCS and that China can control an ADIZ. This is an allusion to the fact that they declared an ADIZ in the East China Sea and haven’t been able to effectively control that given the amount of commercial air traffic there and the international community’s ire [should the Chinese] try to implement something that restrictive. It may be different in the South, and they may be practicing ‘salami slicing’ where they may just be slicing the slices very thinly to get to the point where they can implement the ADIZ. We should expect more flights of this nature, including flights down to the three new naval air stations.

Regarding the SCS exercise closure areas, I don’t know if those were timed ahead of time. One can imagine they were planned ahead of time knowing the ruling was going to come out sometime this summer, and that the PLAN had been prepared to conduct an exercise and were waiting for the timing to be right. I don’t know that for a fact, but I am just going off your assumption that it may have been already planned. The fact of the matter is they used the exercise to heighten and emphasize their displeasure at this ruling. I think that’s the real key, which is to say that it’s not just words and rhetoric, but it is actual physical movement of naval forces and other forces into the region or around the region in a show of force to the United States and the rest of the world.

The intention is to say, “not only are we (China) saying we don’t agree, but we will physically not agree with this ruling.” I think that’s the real question about how the United States should respond. I would submit that we need to sustain our commitment to the presence that we have demonstrated this year such as the dual carrier ops, the continued Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS), the continued presence that we’ve displayed over 7 decades needs to sustain itself, and we need not fear that there will be conflict started because we’re down in the same water space. I don’t believe that the PRC, at this time, are ready to start a shooting war. They’re pretty upset, they may get very close, but they recognize they have too much to gamble, too much to lose, both internally and externally, for their dream of restoration and rejuvenation. I think you saw that even recently with some of the press reporting that the Chinese press is clamping down on internal protesters [sending the message that] patriotism is good, we understand why you’re upset because this ruling is abhorrent to us, but you don’t have to demonstrate your patriotism by protesting in front of a Kentucky Fried Chicken outlet.

SD: That was an interesting choice! Going on that same theme, you’ve talked about how the U.S. can counter this escalation or perceived escalation. Are continued FONOPS something you’d like to see there as well?

JF: I think we need to do that, I think there’s been a lot written about that in the last week or so. Bonnie Glaser has written about that. I actually agree with her position that we should do [FONOPS] but not announce them or provide advanced warning. I disagree with her when she said [the U.S.] shouldn’t tell people what we’ve done. I think there is a process to report these out post-facto, post-event, to say “here’s what we’ve done this year and here’s the legal reasons why.” I think that’s important, but to advertise them ahead of time, to put our sailors in harms way, I think is not very smart.

I think we should not just [conduct] the FONOPS, which typically are a single ship or aircraft, but [consider] doing more naval exercises in the region unilaterally, but also bilaterally and multilaterally. I think the more we demonstrate that these are waters that anyone can work in and that China is going to have a tough time covering exercises down in the SCS and ECS.

One example is ANNUALEX with the JMSDF. We should be [conducting] ANNUALEX west of Okinawa to send this message to the Chinese: if you really want to prevent people from exercising their militaries all over the first island chain, then you’re going to be stretched very thin. Some would say, maybe the Chinese can match us ship for ship, and maybe they can against the U.S. 7th fleet today. But they cannot [do so] against the allied naval forces of the region and that’s the real strong position there. If we take that, we will demonstrate to China that they need to change their behaviors.

SD: Going back to your point about FONOPS and pre-announcing them, I think the point has been made that the announcement itself implies some sort of wrongdoing. If we truly believe that its freedom of navigation and that these are international waters then there should be no need to announce. Is that what you are saying?

JF: Yeah, I think it’s daily business, just going about daily operations. If [warships] happen to sail through some place that is disputed, then they do that or they don’t do that, but they don’t have to make a big deal out of it. And I would say that there’s a nuance here. You don’t have to make a big deal out of it not because you’re concerned that China is going to get upset, and granted I don’t think we should go out of our way to antagonize China, but we should not limit our actions because we’re always concerned about that, which seems to be what we normally do. I think we don’t advertise for the security and safety of the sailors who are now going to be put in a position where someone knows they’re coming and may set up an ambush or a set of circumstances that could cause someone to lose their life. That’s really why I don’t think we should pre-announce the FONOPS.

SD: Its not hard to imagine a scenario where, intentional or not, something could happen. Accidents happen at sea, especially when ships are getting close, so that could be escalatory. Your point is very well taken.

JF: I think that the position here is nuanced, because there’s many inside the “China-watching” community that are suggesting we don’t want to embarrass or upset or provoke China. That seems to be our constant concern before acting in our national security interest. The U.S. seems to be more concerned about not upsetting [China] because there’s this belief that if we do, then our national security will be worse off.

I don’t think the evidence supports that logic over the last decade, but that still seems to be the predominant mindset, which is “provoking China makes things worse.” Instead of saying that China is the [party providing the provocation] and changing the status quo, not following their own declared and signed declarations like the ASEAN code of conduct from 2002, or even their signature on UNCLOS. The court of arbitration was very clear in its message, ‘you signed into this, China, you agreed to follow these rules and now you don’t want to.’ I think that’s the issue, and not so much that the U.S. is somehow parachuted into the SCS in the last two years and caused everyone to get upset. We’ve been there a long time, and we’ve given everybody a great opportunity to raise their standard of living across Asia, including China. We need to reject this notion that we’re the problem, and we need to start identifying that China is the problem. If we cant do that, they’re going to continue to take advantage of this [narrative].

SD: It was reported that China approached the Philippines for bilateral talks with the condition that both parties agreed to disregard the UN Court’s ruling. The Chinese did not even want to broach the subject at said talks and the Philippines declined to talk with these conditions. Is this an attempt by China to save face and does this indicate to you that there’s a politically acceptable way for an agreement on the outside of this ruling?

JF: It was informative to see the Philippines’ response under the new Duterte administration. There was some concern in certain circles in China and outside about [what] Duterte’s approach to China [would be]. Now on this first overture by the PRC, it is clear that the Philippines are not going to accept this kind of [off the table negotiation.] They won’t set aside the ruling and say that’s not valid.

This represents a classic Chinese approach. I live up here in the Alps and I see a lot of these granite rocks, and sometimes the rocks crumble off the face and crash down. They do that because every winter, water comes in and finds the smallest crevice, freezes, and expands. It does that over time and then finally the rock cracks and gives way. The Chinese approach to diplomacy is like this, find the smallest little crack, the smallest little diplomatic nuance or change in language, and try to break someone off from their core interest, and if you accept that you’ll be separated from your strategic national objective.

In this case, they suggested they could work with the Philippines, as long as they said the ruling was invalid and they’re not going to accept it. Maybe the Philippines will, and maybe they wont, but right now they’ve said no. I think it should be informative to people to watch how the Chinese approach these things. That’s the soft sell. There’s the hard sell, which is the bomber overflight, the declaration of SCS exercise areas, there’s the speech that Admiral Wu gave to Admiral Richardson, and then there’ll be this behind-closed-doors deal making.

SD: How much of the Philippines’ calculus on rejecting these talks has to do with the fact that they tried that angle with China over Scarborough Shoal in 2012 and were betrayed? China did not uphold their side of the deal.

JF: I think that’s an excellent point, and now some would say “how much does the new administration know about what happened in 2012?” I think most people in the Philippines do know that they were hoodwinked by the Chinese in that agreement. Their fingers are still numb from being burned before. So they’re less likely to buy into something like this. But, China is very persuasive in their soft power attempts and so things like business opportunities for Philippines in China and visa versa. These will all be brought up in closed door sessions, away from the media, and there’ll be extreme pressure exerted on this administration to dismiss this ruling and “go from there.” But you can go back to 2002 and say the same thing, China told everyone they agreed that no one should change the status quo in the SCS, and then they did over the next 14 years. China has a track record of saying one thing and doing something else. I think the more people are exposed to this through bad experiences ,the less inclined they are to buy into it again.

SD: So, if that “soft sell” is rejected, how do you see the Chinese responding? How will they amend their strategy, this two-pronged approach of soft and hard sell, if nobody’s buying anymore? What’s next for China?

JF: As I mentioned earlier, possession is nine tenths of the law. They’re betting that no one is going to launch a major naval operation or invasion of these islands to kick them out based on the PCA’s ruling. I don’t think anyone on the planet is planning to do that or would want to do that. I think China knows that. So the reality is, what do we do from here? Where do we go from here? Is there a way to stop China’s expansionism? Well, Scarborough Shoal will be that test. They’ve built up most of the islands that they want in the Spratlys, Second Thomas Shoal is another one, there’s the grounded LST Sierra Madre they could try to physically take, so the Philippines and our allies need to watch for that.

China’s already been vociferous over the last 5-6 years; since 1999 they’re been very upset about this. Now, with the ruling out, they may use this as one of those areas to seize in the middle of the night. [China could] come in with a bunch of warships in the cover of darkness against a poor indications and warnings network. We need to watch Second Thomas Shoal, we need to watch Reed Bank, [there are places] that China could just move in and begin dredging. Scarborough, clearly, is a place where the Chinese already have a toe hold, they have a section of it, so it would be easy for them to try to do something. The U.S., Philippines, and other allies in the region have to ask themselves what they’re going to do to physically prevent China from doing this. Taking back Mischief Reef, Fiery Cross, Subi Reef, or Caurteron Reef is going to be hard and nobody really wants to do that. Those may be gone forever.

The other areas I just mentioned are areas where [the U.S. and its allies] can go on a routine basis and show continuous presence, which is going to require more than the 60/40 split from the U.S. Navy. It is going to require more assets, it may require our Coast Guard, it may require other nations’ Coast Guards to be physically present and prevent China from [taking ownership of these features]. That would be the strongest signal we could send, and it would require not just ships, but subs and also aircraft, and reconnaissance flights with fighter escorts. This would get across to China that they really crossed a line without publicizing red lines, and without getting into that geopolitical mess, just a physical presence. I think what we’ve seen with the [USS] Stennis Strike Group’s operations are a nod to that, but now it’s got to be more than just high profile exercises and dual carrier ops. It has to be a commitment to a daily presence. Otherwise, China knows they will be there daily, having increased their presence in the SCS by my own estimates at last tenfold. They have a lot of platforms from the Coast Guard and Navy that are in and around those waters 24/7/365. If we really want to stop them from expanding, we’re going to have to be there and match them hull for hull in some sense.

SD: Understood. I want to wrap up with this question on how the disparity between the Chinese response to this ruling and the American public’s response could not be more disparate. Having a presence there will cost money and will take increased investment and a larger navy. How can we as navalists, or China watchers, communicate to the larger American public the importance of this issue?

JF: You’re exactly right. It will take a larger navy. I think that’s a topic of discussion [for] one of the parties in this upcoming election cycle. What’s the size of our navy and is it big enough to do the kinds of things we need it to do? There’s arguments on both sides that there’s not enough money to procure this, and even if we had the money, it would take years to get. That’s a difficult issue. But we need to address [the need for a larger Navy] in a dialogue with the American people. As I mentioned before, it’s the responsibility of senior naval leadership to articulate this message to our senior policymakers, and to make it something that gets articulated to the American people. When I talked to a naval officer a week ago, after the ruling had come out, the response I got was ‘hey, these are just a bunch of rocks, and they have no bearing on U.S. National Security.’ That really troubles me.

In the 1980s, when Secretary of the Navy Lehman helped create the maritime strategy, there was no question about our national objective of making sure that the spread of communism didn’t go worldwide. There was no question that the U.S. Navy was a key part of that national objective. We need to have naval leaders explain to the American public and policy makers from both parties that the reason we need this large Navy is because if China can control the SCS and can control who can come in and out, (even though they’ve denied that they will do that, we do have knowledge that they may have plans to do that), this will adversely affect our national interests, the interests of all the countries in the region, and the global economy. We need to have leaders that are going to be more forceful in articulating this requirement. The pivot, the re-balance, is one step. The 60/40 split that [the U.S.] announced for our Navy is good, some of the new capabilities that we’re bringing out there like the P-8, Virginia-class submarines, and Zumwalt-class destroyers, are all good uses of our bully pulpit with the resources that we have.

But I’m concerned when I see things like our State Department giving an anemic response the day after the PCA ruling. [The statement] basically equivocated and said that China and the Philippines are co-equals in the ruling and they both need to pay attention to it. We had a chance, in that small window, to come out and endorse international law, this ruling, and [state] that we will back it up with not only our own physical forces but those of our allies. This would build on cooperation of nations to suppress China’s unilateral aggressive behavior; we missed that opportunity. I’m still waiting from the State Department’s detailed analysis of the ruling. It’s now been well over a week and a half, and we still don’t have that, yet, very smart people like Jerome Cohen have already come out with a detailed analysis of the court’s 500 plus page ruling and given it an endorsement. I think this is the kind of comprehensive national power that China applies to a problem that we seem to be lacking. I think we need to come together on this. Otherwise we risk our ability to say that Freedom of Navigation is around the world.

SD: There’s a fundamental misunderstanding, coming back to your “bunch of rocks” quote, where the U.S. Navy has been the arbiter of the freedom of the global commons for a long time now, and it has fostered a system that has allowed people to raise their standard of living and a successful global system that is unprecedented. Perhaps people don’t appreciate the U.S. Navy’s role in that.

JF: If you believe that, and not everyone does, but if the people within the [U.S. Navy and U.S. policy making bodies], can’t get unified on that belief, then we’re going to fail in articulating that to the American public. Especially in times when we’re in crisis in other areas of maritime endeavors, like Russia and what’s going on in the Mediterranean, Syria, Iran, and the threats that they’re making to naval forces in the Persian Gulf. These [issues] are not just isolated to the East Asian arena. This is a global issue. We’ve been a global navy. People say we can’t be the world’s cop, okay got it, maybe not in different land areas, but we have been committed to being the ‘world’s cop’ in the maritime domain.

If we’re not going to do that, let’s have a discussion about that as a nation and let’s save billions of dollars and cut back, bring the 7th fleet back to Hawaii or San Diego, quit building Ford-class nuclear aircraft carriers, SSBN(X), etc. There are a lot of things that are implied in this idea of standing down from being a global navy. We are being challenged right now in East Asia. It is not just in the SCS, but the ECS as well, and Japan will be one of the next points of attack for the Chinese based on how they do in this SCS scenario.

SD: It has been an honor to speak with you today, Sir. I’m sure that there will be a lot more to discuss on this topic in the future, and I hope you will join us again. If our readers want to subscribe to Red Star Rising, and I recommend they do, how can they do so?

JF: Interested readers can subscribe to Red Star Rising by contacting me at kimo.fanell@gmail.com.

Captain James Fanell, USN (Ret.) is currently serving as a fellow at the Geneva Center for Security Policy. He previously served as Director of Intelligence and Information Operations for the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet.

Sally DeBoer is the President of CIMSEC, and also serves as CIMSEC’s Book Review Coordinator. Contact her at President@cimsec.org.