Feature Picture: LÉ Samuel Beckett the latest OPV of the Irish Naval Service (Trilogy Corporate Site 2014)

Geographical and Oceanographical Factors

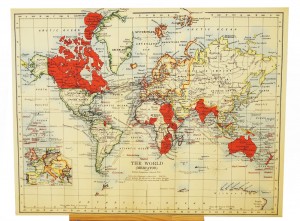

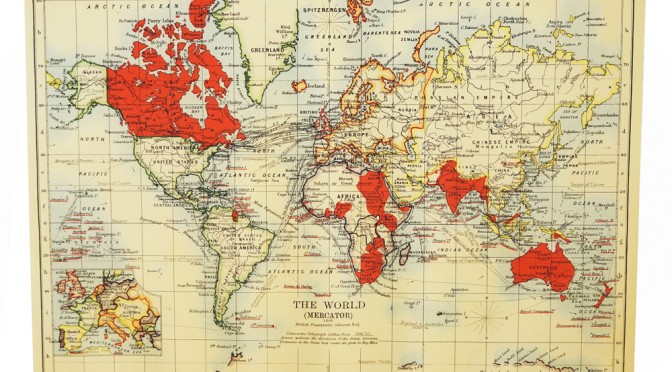

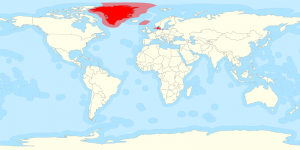

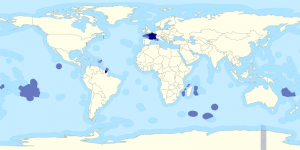

When designing OPVs the core question a nation will need to ask itself is how big in terms of area, where the EEZ is (i.e. Northern waters, or Equatorial waters), how far is it that area from the nation’s bases and how much is the EEZ worth. Vessels which are required to operate in stormy or icy waters (i.e. those operated by Denmark) will need to be as structurally strong and survivable as possible, with a high freeboard to help with large waves, as well as having as much of their equipment internalised as can be, and all equipment that can’t be internalised made easy to clear of ice. In contrast vessels which are to operate in warmer areas (i.e. to an extent France) will need enhanced cooling systems, not only to keep the personnel at a workable temperature, but also the computers and machines. A vessel which could find itself in both situations equally (i.e. those operated by Australia or Britain), will of course need both attributes; it is very difficult to retrofit sufficient cooling into a small ship built to be strong, equally it is very difficult to strength a ship that is not built to be strong. Simply put, a lot of thought needs to be placed at the very beginning of the conception and design process with OPVs as to what is needed, what is wanted and what is best to make sure: because there is not the space available to do much rectifying at a later date.

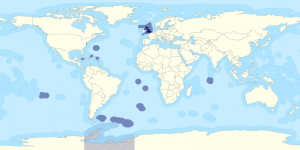

Figure 8. Denmark’s EEZ, total area of 2,551,238km2 encompasses a large area of North Atlantic and the Arctic[i] Figure 8. Denmark’s EEZ, total area of 2,551,238km2 encompasses a large area of North Atlantic and the Arctic[i] |

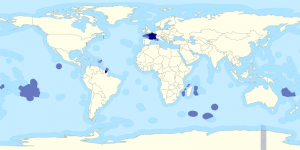

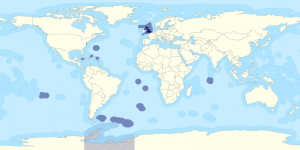

Figure 9. France’s EEZ totals in at 11,035,000km2 and is spread all around the world[ii] Figure 9. France’s EEZ totals in at 11,035,000km2 and is spread all around the world[ii] |

Figure 10. Australia’s EEZ, total area of about 8,505,348km2 that straddles the South Pacific and Indian Oceans, whilst encompassing a large chunk of Antarctica[iii] Figure 10. Australia’s EEZ, total area of about 8,505,348km2 that straddles the South Pacific and Indian Oceans, whilst encompassing a large chunk of Antarctica[iii] |

Supplementary Missions

OPVs, especially those deployed to patrol distant territories or honour commitments to allies, will often be the nation they represent first responders to natural disasters; therefore building a measure of preparation into the design, i.e. storage space for medical supplies, power tools, tents and portable water purification equipment would be of advantage. This is a situation where a nation has the opportunity to engage in a win-win scenario; they help another nation (nations are not altruistic but they do like to look good and earn favours), they get to build a closer relationship with the nation experiencing the disaster and that nation gets some help. Much the same can be said for an OPV’s role in Search and Rescue operations, most nations have some form of lifeboat organisation – whether it is part of the government, independent or a mix differs from nation to nation. OPVs are of course not lifeboats, but if they are present then they can again be crucial first responders, especially in the case of mid-ocean emergencies. There is though a war (or at least combat) orientated mission, which has been highlighted by the events of October 2014 in Sweden; anti-submarine warfare, or ASW[iv].

Figure 11. HDMS Ejnar Mikkelsen a Knud Rasmussen class OPV of the Danish Navy[v] Figure 11. HDMS Ejnar Mikkelsen a Knud Rasmussen class OPV of the Danish Navy[v] |

Now it is reasonable to pose the question ‘how useful could a vessel without a sonar (with the exception of the Danish Knud Rasmussen class[vi] which take advantage of stanflex technology[vii] to acquire one) or torpedoes be to an ASW operation, after all it isn’t a frigate?’ In fact OPVs, even those being proposed in this paper are not even corvettes (being closest in armament to a gunboats), do have something to offer ASW operations, especially those with the ability to support helicopters and operate UAVs. Helicopters have become the cornerstone of ASW operations; whilst Long Range Maritime Patrol Aircraft and ships with towed sonar arrays are very capable assets which really do make a difference: a legacy of the Cold War has been an almost dominance of helicopters in the practice of ASW[viii]. Helicopters of course make use of sonar buoys and dipping sonar to locate enemy submarines, such equipment could also be transferred in time to suitably capable UAVs – some of which are already in operation[ix]. This is in many ways an argument for building in flexible spaces into ship designs, as the one thing that can’t be easily added into a ship is space, yet it is space which serves best to future proof it.

It’s not only ships though that need to be future proofed, so do crews and commanders. Small ships, like OPVs, offer almost unique opportunities for navies to test out commanders at junior ranks with a fair amount of responsibility; at a far lower risk than if the achieve higher rank and untested make their mistakes when in command of far more expensive vessels. Furthermore, a naval commander will often find themselves acting in a diplomatic capacity[x] a fact which has been highlighted by Julian Corbett as well as other authors[xi] throughout the years. Therefore Command of an OPV, especially when despatched to the edges of an EEZ or to patrol distant territories will provide young officers a plethora of opportunities to develop their skills and gain vital experience in this role. The reason that OPVs are unique in this regard is because the other small vessel type, the mine countermeasure vessel (MCMV), is becoming more and more specialised – even as the equipment becomes more containerised and dependent upon unmanned vehicles (although divers retain a vital role in the work); meaning that command of such vessels acting in that role itself requires more and more specialised knowledge.

Possible Missions

“The unassailable political lessons of the Falklands are that disregarding a threat does not make it disappear”

James Cable[xii]

The same can be said for ships, and most definitely for OPVs – disregarding, or down playing the likelihood of circumstances that will require their capabilities doesn’t mean it won’t happen. Even in this work, there are possible missions which OPVs could be used for, beyond those it has discussed. For example, with a suitable CIWS, and dual-purpose deck gun these vessels could make a very much needed war time point defence assets for MCMVs, auxiliaries, ships taken up from trade[xiii] and amphibious ships (including landing craft). In a time of shrinking forces, these are not frigate or destroyer replacements, but they would be able to help; they are able to be the ‘quantity’. Which leads to another scenario for the future. That OPVs cease to exist as they are now, and that nations begin to pursue something more similar to where the Danish model has already gone.

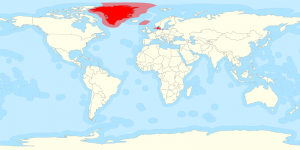

Under this scenario the future is a ship of ~2400tons, with a range of 6-7,000nmi, and which in its basic OPV form is armed with probably either a 57mm or 76mm deck gun[xiv], a CIWS and two single 20mm or 30mm mounts, would carry a rotary UAV and have the ability to deploy and recover boats from a ramp. However, by making use of a system similar to that of the Stanflex modular system, can be quickly modified with additional modules[xv] to make it an MCMV, Oceanography vessel or Point Defence ship (with addition of self-sufficient surface to air missiles which don’t require specialist radar, like the C-Dome is reported to be[xvi]) as required by operation. Although to maintain those skills and to meet ongoing operational commitments some vessels would have to be virtually permanently tasked as the former two; with other ships taking over as required by maintenance. This is because as said above the work of MCMV vessels is particularly specialised, and requires a lot of practice to keep at the level it’s required for war time. Oceanography is of course and ongoing commitment, requiring its own cadre of specialised staff, and equipment, which are easier to leave in place as long as possible so they can ‘bed down’. This all though is not to mean that there are not significant requirements for British Patrol vessels, as Figure 12 (below) highlights; the British EEZ is very expansive.

Figure 12. Britain’s EEZ incorporates an area over 6,805,586km2, and whilst world encompassing is concentrated in the Atlantic[xvii] Figure 12. Britain’s EEZ incorporates an area over 6,805,586km2, and whilst world encompassing is concentrated in the Atlantic[xvii] |

In the case of the Royal Navy which is currently upgrading its forces to seven River Class OPV’s, operates eight each of the Hunt and Sandown class MCMVs, two Echo Class multi-purpose survey vessels, representing a force of twenty-five ships. Now if all those ships were of the same design, then instead of it being seven OPVs, sixteen MCMVs and two survey vessels, it would be a pool of twenty five vessels (with operational cost savings from streamlining training and maintenance that could be twenty-eight, or even more should Britain continue its focus on reserves and decide to give the Royal Naval Reserve proper ships again[xviii]) that could be orientated as required by circumstance.

Now this is nothing new, the RN’s MCMVs already often do secondary duty as OPVs, and in fact the scenario outlined is to an extent (common hulls), what the Mine Countermeasures, Hydrography and Patrol Vessel (MCHPV) program envisaged[xix]. Unfortunately, and despite the publication of the Black Swan sloop Concept[xx], when the opportunity came to order three more ships for the OPV role – it was not this program which was sourced, but the existing River Class[xxi], suggesting that it has at least been put back if not having been sacrificed for the time being on the altar of the Type 26 Frigate. What is worse is actually the base design of the River class, with its proven track record, adaptability and RN operational experience, would actually (on the face of it) make the perfect base pattern for the MCHPV to be built from. Britain though would not be the only nation which could benefit from such a design, so could other nations such as Japan, South Africa, India, Australia and Canada.

All those nations are nations which are building themselves up in the maritime sense, they have to really, as the world has got more complex and sources of danger have diversified the necessity to protect what is theirs has grown. For the Japanese who have a strong escort force they would be most likely less interested in the point-defence adaptability, but considering their ‘peacetime’ problems of East China Sea EEZ patrol and probable war time issues with mines an adaptable force could prove a very workable and cost effective solution. For Australia and Canada with such vast areas to cover in such hostile seas then the more OPVs the better, more importantly with their relatively small force sizes, some second tier fighting ships might well be an attractive foundation on which to grow operational capabilities. India which has for a long time prided itself on being the strongest Asian naval power, is now facing challenges and a future where there are now easy strategic choices or even black & white decisions – making procurement of a flexible asset of the form of OPV/specialist duty vessel a more practical methodology of future proofing.

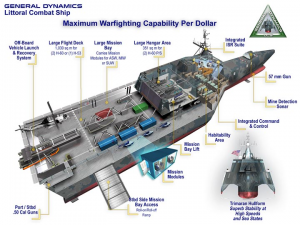

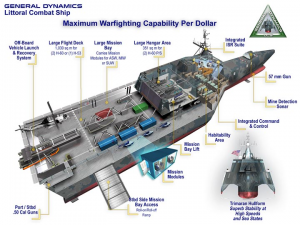

This is though beginning to sound similar to a ship design which has dominated American procurement discussion in recent years, the Littoral Combat Ship or LCS[xxii]. This was billed as the go everywhere, do everything low level combatant. Which has become its millstone, because it was supposed to be a jack of all trades it is good at none. Everything was designed from scratch, tailor made to fit this new class of warship. Unfortunately that design included a fixation on stealth, primarily because of the ‘Littoral’, meaning close to shore, in its name. The important difference between the LCS, OPVs and even what is being proposed is that the latter two vessel types are not supposed to do everything. The whole way through this work a constant refrain has been, ‘not a frigate’; OPVs do not need to be stealthy to the extent of the LCS, they do no need multiple hangars or even custom equipment – because that level of equipment is not needed by their mission set. Everything that an OPV needs, even the adaptable ship proposed in this section, is procurable ‘off the shelf’ – theoretically offering governments the opportunity to keep very tight control of the costs because they are known in advance. Even with all its capability the LCS has because of its failure to be able to do everything, had its procurement cut short and the USN are now looking for a frigate. One of the options for which is actually an upgraded version of the Coast Guards National Security Cutter[xxiii].

Figure 13. the Austral’s Independence class LCS, the second of the two designs, its trimaran hull form and distinctive menacing stealth design has already made it a feature of cinema, but also make it cost wise firmly in the frigate classification, despite its limited weaponry[xxiv]. Figure 13. the Austral’s Independence class LCS, the second of the two designs, its trimaran hull form and distinctive menacing stealth design has already made it a feature of cinema, but also make it cost wise firmly in the frigate classification, despite its limited weaponry[xxiv]. |

Figure 14. Russian Steregushchiy class corvette[xxv], the Russian equivalent of the LCS, it bristles with weapons and is not really adaptable: these vessels (like the Chinese Type 056) are most definitely small warships rather than a patrol vessel. Figure 14. Russian Steregushchiy class corvette[xxv], the Russian equivalent of the LCS, it bristles with weapons and is not really adaptable: these vessels (like the Chinese Type 056) are most definitely small warships rather than a patrol vessel. |

Conclusion

“…the greatest value of the Navy will be found in events that fail to occur because of its influence”

Prof. Colin Gray[xxvi]

As has hopefully been shown these words of Prof Gray could be the watchwords for OPVs. Whether in terms of design or employment, the mission of such a vessel is to prevent events from happening through their own presence, and through the influence that being present gives a nation.

At the beginning of this work a very simple question was asked, ‘What do OPVs need to be able to do, to do what they do?’, the answer unfortunately is not so simple. The first part of the question though that needs to be answered is actually the second. This is because what a ship does is ultimately the crucial overarching idea which must dictate their design. In theory the OPVs overarching design idea is to be able to maintain their nation’s EEZ through patrolling, and maximise their nation’s security in general through presence. The trouble is that, whilst put like that it sounds like a two plus two sum scenario, the reality as has been discussed is far more complex. There are reasons that the Nigerian OPV version of the Chinese corvette displaces 300tons more; to start with it is operating primarily in the South Atlantic rather than the more gentle waters of the Pacific, beyond this is the fact that whereas the corvettes can call in support of larger ships – the Nigerian navy hasn’t yet reached that point. This serves as an example as to why it’s so difficult to compare one nations OPV to another’s, as every nation has unique needs, and an its own global perspective which will impact upon what they think they need, therefore what they build.

This complexity then feeds into the first part of the question, for if a vessel is conceived to carry out a primarily fishery protection role then it’s armament beyond machine guns becomes rather unnecessary; if however it is likely to be facing off with other nations warships – then perhaps it needs to be more corvette/small frigate, less OPV. The trick for any nation will be in getting the balance right, because getting it wrong will be far more expensive in lives and treasure. To get it right though then a nation must first properly gauge the threat that its ships will likely face, and just as importantly what level of support they are likely to receive – for a ship that will be on its own and only receive support under the best of circumstance must by necessity be more self-sufficient than one for which possibly overwhelming firepower, medical support or stores are just a beep away.

OPV are because of all this a very revealing class of vessel to watch, by this it’s meant that a nation’s choices will demonstrate much about what their intentions are. The longer the endurance of an OPV the more a nation would seem to be intent on achieving constant presence within their EEZ. This though is not answering the question, the answer to the question is that once a nation has decided what it needs to do, and what it wants to do then it must equip its OPVs accordingly; but they can’t go too far wrong if that OPV is equipped with UAVs, a decent deck gun, a CIWS, the appropriate sensors and possibly most importantly the ability to rapidly deploy and recover boats. Everything beyond that is up to the nation involved.

Dr. Alexander Clarke is our friend from the Phoenix Think Tank in the United Kingdom and host of the East-Atlantic edition of Sea Control.

———————————————————————————-

[i] (Wikipedia 2014, Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) 2009)

[ii] (Wikipedia 2014, Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) 2009)

[iii] (Wikipedia 2014, Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) 2009)

[iv] (Marzal 2014)

[v] (www.prismdefence.com 2010)

[vi] (CASR 2008, naval-technology.com 2014)

[vii] (Seaforces.org 2014) – this is a brilliant system which allows for a whole range of mission modules to be changed in and out re-rolling a ship in a matter of hours; advantages of this system include reducing maintenance & upgrade costs – by being able to carry out the work inside at a pace dictated by the work, not by the need to get the ship back to sea. The problem with it are that whilst it is really a better version of ‘fitted for not with’ (a famous phrase attached to many RN vessels), as the ships can be fitted very quickly, a small ship will always be restricted to being a general specialist rather a general purpose ship. That though is really not that big a bug to bear.

[viii] (Holmes 2014, USN 2014)

[ix] (Clarke, August 2013 Notes: Possibilities of Future RN AEW 2013, Clarke, August 2013 Notes: UAVs = Cruise Missiles = UAVs… what does the future look like for Navies? 2013)

[x] (Clarke, August 2013 Thoughts: Naval Diplomacy – from the Amerigo Vespucci to a Royal Yacht 2013)

[xi] (J. S. Corbett 1911, Lord Chatfield 1942, Cable, Gunboat Diplomacy 1919-1979, Political Applications of Limited Naval Force 1981, Mahan 1987)

[xii] (Cable, Britain’s Naval Future 1983, xiii-xiv)

[xiii] Which have been a part of warfare forever, and have been a core part of war time planning for many years – as best displayed in the work the USN did on War Plan Orange (Miller 1991, 86-99)

[xiv] In the case of the UK which seems to have enforced a no new gun policy, then there would seem to be a perfect opportunity for some inter-service collaboration, the new army 40mm gun would seem ripe for a sea going conversion, and whilst not being much better than the 30mm option, it would provide a better than nothing increase whilst not requiring a new gun.

[xv] Optimum number would probably be two – four, depending upon whether the CIWS and Deck Gun were also modular installations or were traditionally emplaced.

[xvi] (Eshel 2014)

[xvii] (Wikipedia 2014, Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) 2009)

[xviii] Yes this may look a little ‘pie in the sky’ in the light of recent decisions, but considering even a cursory glance at what this force is required to do includes:

- Provide presence/maritime security patrols in the Caribbean, Gibraltar and the Falklands; the only one that a standing OPV presence is maintained at the moment is the Falkland’s, with the Caribbean being covered by a Bay class auxiliary, and Gibraltar having something only when it’s passing through.

- Fishery Protection/Counter Terrorism patrol of the UK; the OPVs are constant alert for this, whilst Scotland maintains its own Fishery Protection vessels, they don’t do counter terrorism.

- MCMV patrols in the Middle East, Faslane for the Strategic Deterrent, Portsmouth for the Carriers and Plymouth for the Amphibious Task Group; possibly the most overworked vessels in the fleet, with

- Survey Ships are often either doing or doing the equivalent of around the world voyages in order to maintain up-to-date maps of the oceans beneath the waves to support ASW and submarine operations.

When that is considered, alongside the fact that many of these commitments requiring multiple ships, it could make anyone wonder how the RN manages it with a force of just 25 vessels – which are not ‘interchangeable’ as those proposed would be.

[xix] (naval-technology.com 2012)

[xx] (Ministry of Defence 2012)

[xxi] (Navy News 2014)

[xxii] (Defence Industry Daily Staff 2014)

[xxiii] (Axe 2014)

[xxiv] (Defence Industry Daily Staff 2014)

[xxv] (naval-technology.com 2014)

[xxvi] (Royal Navy 2014)

Bibliography

Agencies. 2014. “’Unrealistic’ for Turkey to send ground troops to Syria.” The Telegraph. 09 October. Accessed November 16, 2014. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/islamic-state/11151562/Unrealistic-for-Turkey-to-send-ground-troops-to-Syria.html.

Anzalone, Joseph. 2010. “The Virtue of a Proportional Response: The United States Stance Against the Convention on Cluster Munitions.” Pace International Law Review 22 (1): 183-211. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1028&context=pilr.

Axe, David. 2014. “One of These Mean Little Ships Could Be the Navy’s New Frigate; Pentagon wants a tougher warship to replace the Littoral Combat Ship.” War Is Boring. 24 February. Accessed November 17, 2014. https://medium.com/war-is-boring/one-of-these-mean-little-ships-could-be-the-navys-new-frigate-ebf51ce106fe.

Babij, Orest. 2009. “The Royal Navy and Defence of the Empire 1928-34.” In Far-Flung Lines; Studies in Imperial Defence in Honour of Donald Mackenzie Schurman, edited by Keith Neilson and Greg Kennedy, 171-189. London: Routledge.

Bacon, Reginald, and F E McMurtrie. 1940. Modern Naval Strategy. London: Frederick Muller.

Bannister, Sam. 2014. “Portsmouth ship HMS Dragon now tracks Russian Navy task group.” The News. 08 May. Accessed November 12, 2014. http://www.portsmouth.co.uk/news/defence/portsmouth-ship-hms-dragon-now-tracks-russian-navy-task-group-1-6047308.

BBC. 2014. “Canberra monitoring Russian warships ‘nearing Australia’.” BBC News – Australia. 13 November. Accessed November 14, 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-australia-30032466.

—. 2009. “China hits out at US on navy row.” BBC News. 10 March. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/7934138.stm.

—. 2014. “China ‘spy ship’ at US-led navy exercise off Hawaii.” BBC News China. 21 July. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-28400745.

—. 2014. “Q&A: South China Sea dispute.” BBC News ASIA. 8 May. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-13748349.

Beaumont, Peter. 2014. “How effective is Isis compared with the Iraqi army and Kurdish peshmerga?” The Guardian. 12 June. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/12/how-battle-ready-isis-iraqi-army-peshmerga.

Beehner, Lionel. 2006. “Israel and the Doctrine of Proportionality.” Council on Foreign Relations. 13 July. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.cfr.org/israel/israel-doctrine-proportionality/p11115.

Boeing. 2014. “ScanEagle.” Boeing; Defense, Space & Security . Accessed November 05, 2014. http://www.boeing.com/boeing/defense-space/military/scaneagle/.

Cable, James. 1983. Britain’s Naval Future. London: Macmillan Press.

—. 1981. Gunboat Diplomacy 1919-1979, Political Applications of Limited Naval Force. London: Macmillan, Studies in International Security.

CASR. 2008. “An Overview of Current, On-Going Danish Naval projects 2005-2009.” CASR. May. Accessed November 05, 2014. http://www.casr.ca/id-danish-naval-projects-rasmussen.htm.

Chinese Military Review. 2013. “Multiple Chinese Type 056 Light Corvette @ Naval Base .” Chinese Military Review. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://chinesemilitaryreview.blogspot.co.uk/2013/07/multiple-chinese-type-056-light.html.

Clapp, Michael, and Ewen Southby-Tailyour. 1997. Amphibious Assault Falklands, The Battle of San Carlos Water. London: Orion Books.

Clarke, Alexander. 2013. “August 2013 Notes: Possibilities of Future RN AEW.” Naval Requirements. 01 September. Accessed November 05, 2014. http://amphibiousnecessity.blogspot.co.uk/2013/09/august-2013-notes-possibilities-of_1.html.

—. 2013. “August 2013 Notes: UAVs = Cruise Missiles = UAVs… what does the future look like for Navies?” Naval Requirements. 01 September. Accessed November 05, 2014. http://amphibiousnecessity.blogspot.co.uk/2013/09/august-2013-notes-uavs-cruise-missiles.html.

—. 2013. “August 2013 Thoughts: Naval Diplomacy – from the Amerigo Vespucci to a Royal Yacht .” Naval Requirements . 01 September. Accessed November 05, 2014. http://amphibiousnecessity.blogspot.co.uk/2013/09/august-2013-thoughts-naval-diplomacy.html.

—. 2009. “Carriers; Fully Loaded – Admiral Kuznetsov.” Naval Requirements . 20 February. Accessed November 12, 2014. http://amphibiousnecessity.blogspot.co.uk/2009/02/carriers-fully-loaded-admiral-kuznetsov.html.

—. 2013. “October 2013 Thoughts (Extended Thoughts): Time to Think Globally .” Naval Requirements. 02 November. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://amphibiousnecessity.blogspot.co.uk/2013/11/october-2013-thoughts-extended-thoughts.html.

Comcercial Crime Services. 2014. “IMB Piracy & Armed Robbery Map 2014.” ICC Commercial Crime Services. Accessed November 03, 2014. https://www.icc-ccs.org/piracy-reporting-centre/live-piracy-map.

Corbett, Julian S. 1911. Some Principles of Maritime Strategy. Uckfield: The Naval & Military Press Ltd.

Corbett, Julian S. 2005.b. England in the Seven Years War. Vol. II. II vols. London: Elibron CLassics.

—. 2005.a. England in the Seven Years War. Vol. I. II vols. London: Elibron Classics.

Corbett, Julian S., and H. J. Edwards, . 1914. The Cambridge Naval and Military Series. London: Cambridge University Press.

Corcoran, Kieran. 2014. “Royal Navy frigate forced to intercept two Russian military landing craft as they steamed up English Channel.” MailOnline. 26 June. Accessed November 12, 2014. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2670417/Royal-Navy-patrol-ship-forced-intercept-two-Russian-military-landing-craft-steamed-English-Channel.html.

Council on Foreign Relations. 2013. “The Global Regime for Terrorism .” Council on Foreign Relations. 19 June. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.cfr.org/terrorism/global-regime-terrorism/p25729.

Dean, Sarah, Sally Lee, and Freya Noble. 2014. “Showdown in the Coral Sea as navy sends THIRD warship to intercept Russian fleet – while Abbott peels off for breakfast with British PM David Cameron in Sydney ahead of G20 summit.” Mail Online. 14 November. Accessed November 14, 2014. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2833179/US-kept-close-watch-Russian-navy-fleet-heading-Australian-waters-believed-acting-orders-spy-leaders-G20-summit.html.

Dearden, Lizzie. 2014. “Russian sends warships towards Australia as Putin prepares to attend Brisbane G20 summit.” The Independent. 12 November. Accessed November 14, 2014. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/australasia/russian-warships-heading-for-australia-as-putin-prepares-to-attend-brisbane-g20-summit-9855308.html.

Defence Industry Daily Staff. 2014. “LCS: The USA’s Littoral Combat Ships.” Defence Industry Daily. 20 October. Accessed November 15, 2014. http://www.defenseindustrydaily.com/the-usas-new-littoral-combat-ships-updated-01343/.

defenceweb. 2014. “China launches first Nigerian offshore patrol vessel .” DefenceWeb. 30 January. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=33409:china-launches-first-nigerian-offshore-patrol-vessel&catid=51:Sea&Itemid=106.

Defense Industry Daily. 2014. “From Dolphins to Destroyers: The ScanEagle UAV.” Defense Industry Daily. 29 September. Accessed November 05, 2014. http://www.defenseindustrydaily.com/from-dolphins-to-destroyers-the-scaneagle-uav-04933/.

Dingli, Shen, Elizabeth Economy, Richard Haass, Joshua Kurlzntzick, Sheila A. Smith, and Simon Tay. 2013. “China’s Maritime Disputes.” Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.cfr.org/asia-and-pacific/chinas-maritime-disputes/p31345#!/?cid=otr-marketing_use-china_sea_InfoGuide.

Drury, Ian. 2010. “Flashpoint in The Falklands: Argentine anger as British oil rig moves in today and MoD beefs up our forces.” Mail Online. 20 February. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1251901/Falkland-Islands-oil-row-Argentina-warns-UK-complacency.html.

Eshel, Tamir. 2014. “Rafael extends Iron Dome C-RAM to the naval domain.” Defence Update. 26 October. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://defense-update.com/20141026_c-dome.html#.VFgQyWdyaM9.

European Defence Agency. 2014. “European Defence Agency .” European maritime surveillance network reaches operational status. 27 October. Accessed November 03, 2014. https://www.eda.europa.eu/info-hub/news/article/2014/10/27/european-maritime-surveillance-network-reaches-operational-status.

“Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ).” Sea Around Us Project; The Pew Charitable Trusts. Accessed November 04, 2014. http://www.seaaroundus.org/eez/.

Farmer, Ben. 2014. “Russian aircraft carrier sails into English Channel.” TheTelegraph. 08 May. Accessed November 12, 2014. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/10816463/Russian-aircraft-carrier-sails-into-English-Channel.html.

Ferris, John Robert. 1989. Men, Money and Diplomacy; the evolution of British strategic foreign policy, 1919-1926. New York: Cornell University Press.

Field, Andrew. 2004. Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919-1939; planning for war against japan. London: Frank Cass.

Friedman, Norman. 1988. British Carrier Aviation. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Gardner, David. 2011. “Brazil sides with Argentina against Britain as Falklands warship is turned away from Rio.” Mail Online. 11 January. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1346094/Brazil-sides-Argentina-Britain-Falklands-warship-turned-away-Rio.html.

Gorshkov, Sergey Georgiyevich. 1980. The Sea Power of the State. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Halliday, Josh. 2014. “Argentina ‘will seek to punish’ firms that drill for Falklands oil.” the guardian. 12 January. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/12/argentina-falklands-oil-international-courts.

Heydarian, Richard Javad. 2014. “The Great South China Sea Clash: China vs. Vietnam.” The National Interest. 12 August. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://nationalinterest.org/feature/the-great-south-china-sea-clash-china-vs-vietnam-11058.

Holmes, James R. 2014. “Relearning Anti-Submarine Warfare.” The Diplomat. 30 October. Accessed November 16, 2014. http://thediplomat.com/2014/10/relearning-anti-submarine-warfare/.

Horrell, Drew F.T. 1991. “Telepossession Is Nine-Tenths of the Law: The Emerging Industry of Deep Ocean Discovery.” Pace International Law Review 3 (1): 309-362. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1022&context=pilr.

Hosford, Zachary M., and Ely Ratner. 2013. “The Challenge of Chinese Revisionism: The Expanding Role of China’s Non-Military Maritime Vessels.” Center for New American Security. 1 February. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.cnas.org/files/documents/flashpoints/CNAS_Bulletin_HosfordRatner_ChineseRevisionism.pdf.

Insitu. 2013. “ScanEagle System.” Insitu. Accessed November 05, 2014. http://www.insitu.com/systems/scaneagle.

Keiler, Jonathan F. 2009. “The End of Proportionality.” The US Army War College Quarterly Parameters, 53-64. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/parameters/Articles/09spring/keiler.pdf.

LaGrone, Sam. 2014. “Australian MoD: Russian Surface Group Operating Near Northern Border.” USNI News. 12 November. Accessed November 14, 2014. http://news.usni.org/2014/11/12/australian-mod-russian-surface-group-operating-near-northern-border?utm_source=USNI+News&utm_campaign=c0ba89d6d6-USNI_NEWS_DAILY&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_0dd4a1450b-c0ba89d6d6-230392337&mc_cid=c0ba89d6d6&mc_eid=bc692ba7a.

—. 2014. “China Sends Uninvited Spy Ship to RIMPAC.” USNI News. 03 November. Accessed July 18, 2014. http://news.usni.org/2014/07/18/china-sends-uninvited-spy-ship-rimpac.

—. 2014. “Egyptian Patrol Craft Attacked by Ships with Possible Ties to Terrorist Arms Trade.” USNI News. 13 November. Accessed November 14, 2014. http://news.usni.org/2014/11/13/egyptian-patrol-craft-attacked-ships-possible-ties-terrorist-arms-trade?utm_source=USNI+News&utm_campaign=c0ba89d6d6-USNI_NEWS_DAILY&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_0dd4a1450b-c0ba89d6d6-230392337&mc_cid=c0ba89d6d6&mc_eid=bc692.

Larken, Jeremy, Michael Clapp, Alexander Clarke, Julian Thompson, and John Waters. 2010. “Phoenix Think Tank.” The Framework for an objective comprehensive Strategic Defence Review. June. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.phoenixthinktank.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/34-Defence-Version-21-final.pdf.

Lord Chatfield. 1942. The Navy and Defence; The Autobiography of Admiral of the Fleet Lord Chatfield. London: William Heinemann ltd.

MacErlean, Fergal. 2014. “Argentina planning to HIJACK Brit oil rigs in Falklands to halt drilling projects.” Express. 01 June. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.express.co.uk/news/world/479521/Argentina-Oil-Rig-Hijack-President-Cristina-Fernandez-de-Kirchner.

Mahan, A.T. 1987. The Influence of Sea Power Upon History 1660-1783. 5th Edition. New York: Dover Publications Inc.

Marshall, Andrew. 1993. “What happened to the peace dividend?: The end of the Cold War cost thousands of jobs. Andrew Marshall looks at how the world squandered an opportunity.” The Independent. 03 January. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/what-happened-to-the-peace-dividend-the-end-of-the-cold-war-cost-thousands-of-jobs-andrew-marshall-looks-at-how-the-world-squandered-an-opportunity-1476221.html.

Marzal, Andrew. 2014. “Sweden submarine hunt as it happened.” The Telegraph. 20 October. Accessed November 16, 2014. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/sweden/11174169/Sweden-submarine-hunt-as-it-happened.html.

Masi, Alessandria. 2014. “Does the US Need Ground Forces To Fight ISIS in Iraq, Syria? The Impact of Airstrikes Vs. Combat Troops.” International Business Times. 17 September. Accessed November 16, 2014. http://www.ibtimes.com/does-us-need-ground-forces-fight-isis-iraq-syria-impact-airstrikes-vs-combat-troops-1690915.

Menon, Raja. 1998. Maritime Strategy and Continental Wars. Abingdon: Frank Cass Publishers.

Miller, Edward S. 1991. War Plan Orange; The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897-1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Ministry of Defence. 2012. “Joint Concept Note 1/12: Future ‘Black Swan’ Class Sloop-of-War: A Group System.” Gov.uk. 04 May. Accessed November 03, 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/joint-concept-note-1-12-future-black-swan-class-sloop-of-war-a-group-system.

naval-technology.com. 2014. “Knud Rasmussen-Class Ocean Patrol Vessels, Denmark.” naval-technology.com. Accessed November 05, 2014. http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/knud-rasmussen-class/.

—. 2014. “Project 20380 Steregushchy Class Corvettes, Russia .” naval-technology.com. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/steregushchy-class/steregushchy-class1.html.

—. 2014. “Queen Elizabeth Class (CVF), United Kingdom.” naval-technology.com. Accessed November 05, 2014. http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/cvf/.

—. 2012. “Shaping a new breed of mine countermeasure vessels.” naval-technology.com. 13 April. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.naval-technology.com/features/featureshaping-a-new-breed-of-mine-countermeasure-vessels/.

—. 2014. “Type 45 Daring Class Destroyer, United Kingdom.” naval-technology.com. Accessed November 12, 2014. http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/horizon/.

Navy News. 2014. “Work on three new patrol ships to begin in October.” Navy News. 12 August. Accessed November 02, 2014. https://navynews.co.uk/archive/news/item/11085.

navyrecognition.com. 2013. “Holland class Offshore Patrol Vessel (OPV) – Royal Netherlands Navy.” Navy Recognition . 21 August. Accessed November 16, 2014. http://www.navyrecognition.com/index.php/component/content/article/156-royal-netherlands-navy-patrol-vessels/1205-holland-class-offshore-patrol-vessel-opv-p840-hnlms-zeeland-p841-friesland-p842-groningen-p843-royal-netherlands-navy-dutch-koninklijke-marin.

Neilson, Keith, and Greg Kennedy, . 2009. Far Flung Lines; Studies in Imperial Defence in Honour of Donald Mackenzie Schurman. Abingdon: Routledge & Co.

Palmer, Geoffrey, Alvaro Uribe, Joseph Ciechanover Itzhar, and Suleyman Ozdem Sanberk. 2011. “Report of the Secretary-General’s Panel of Inquiry on the 31 May 2010 Flotilla Incident.” UN.org. September. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/middle_east/Gaza_Flotilla_Panel_Report.pdf.

Paul Bremer III, L, and Maurice Sonnenberg. n.d. “Countering The Changing Threat of International Terrorism.” Federation of American Scientists . Accessed November 03, 2014. http://fas.org/irp/threat/commission.html.

Pearlman, Jonathan, and Tom Parfitt. 2014. “Russia sends warships north of Australia in ‘puerile’ display.” The Telegraph. 13 November. Accessed November 14, 2014. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/australiaandthepacific/australia/11227868/Russia-sends-warships-north-of-Australia-in-puerile-display.html.

Rahmat, Ridzwan, and James Hardy. 2014. “PLAN commissions first ASW variant Type 056 corvette.” IHS Jane’s 360. 10 November. Accessed November 16, 2014. http://www.janes.com/article/45600/plan-commissions-first-asw-variant-type-056-corvette.

Royal Navy. 2014. “Atlantic Patrol Tasking South.” Royal Navy. 04 September. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/news-and-latest-activity/operations/south-atlantic/atlantic-patrol-tasking-south.

—. 2014. “HMS Clyde.” Royal Navy. 21 October. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/clyde.

—. 2014. “Royal Navy sails to meet Russian Task Group .” Royal Navy. 08 May. Accessed November 12, 2014. http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/news-and-latest-activity/news/2014/may/08/140508-russian-task-group.

—. 2014. “THE ROYAL NAVY: DEPLOYED FORWARD – OPERATING GLOBALLY, FACT SHEET 1.” Royal Navy. March. Accessed November 12, 2014. http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/About-the-Royal-Navy/~/media/Files/Navy-PDFs/About-the-Royal-Navy/Current%20RN%20Operations.pdf.

Russian Times. 2013. “Argentina cries foul on Falklands oil drilling, threatens 15-year sentences.” Russian Times. 29 November. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://rt.com/news/falkland-oil-drilling-prison-480/.

Seaforces.org. 2014. “Surface Vessel Weapon System; Stanflex Modules.” Seaforces-online, Naval Information. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.seaforces.org/wpnsys/SURFACE/STANFLEX-modules.htm.

Shanker, Thom. 2009. “China harassed U.S. ship, Pentagon says.” The New York Times. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/10/world/americas/10iht-10military.20713498.html.

Smith, Sheila A. 2012. “Japan and the East China Sea Dispute.” Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.cfr.org/japan/japan-east-china-sea-dispute/p28795.

Spelman, Elizabeth. 2013. “The Legality of the Israeli Naval Blockade of the Gaza Strip.” Web Journal of Current Legal Issues. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://webjcli.org/article/view/207/277.

The National Archives. 2014. “The Cabinet Papers 1915-1984.” The National Archives . Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/cabinetpapers/themes/cod-wars.htm.

TheGuardian. 2014. “Beijing removes South China Sea oil rig.” TheGuardian . 16 July. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/16/beijing-removes-south-china-sea-oil-rig.

Tien, Chen-Ya. 1992. Chinese Military Theory, Ancient and Modern. London : Mosaic Press.

Tiezzi, Shannon. 2014. “So China Moved Its Oil Rig. What Now?” The Diplomat . 17 July. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://thediplomat.com/2014/07/so-china-moved-its-oil-rig-what-now/.

Tovey, Alan. 2014. “Boost for defence industry as Navy gets second aircraft carrier.” The Telegraph. 05 September. Accessed November 05, 2014. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/industry/defence/11078025/Britains-largest-warship-nears-completion.html.

Trilogy Corporate Site . 2014. “trilogy network-centric communications.” New Irish OPV commissioned. May. Accessed October 29, 2014. http://www.trilogyus.com/news/news14_irish_opv_update.php.

Tyson, Ann Scott. 2009. “Navy Sends Destroyer to Protect Surveillance Ship After Incident in South China Sea.” The Washington Post. 13 March. Accessed November 03, 2014. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/03/12/AR2009031203264.html.

United States Government Work. 2012. “USCGC Waesche transits the Java Sea during formation exercises.” Coast Guard. 06 June. Accessed November 03, 2014. https://www.flickr.com/photos/coast_guard/7657054940/in/photostream/.

USN. 2014. “Task Force ASW: Anti-Submarine Warfare, Concept of Operations for the 21st century .” America’s Navy. Accessed November 16, 2014. http://www.navy.mil/navydata/policy/asw/asw-conops.pdf.

Wikipedia. 2014. “Exclusive Economic Zone.” Wikipedia. 28 October. Accessed November 04, 2014. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exclusive_economic_zone.

Woodward, Sandy, and Patrick Robisnon. 2003. One Hundred Days, The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander. London: Harper Collins.

www.prismdefence.com. 2010. “Lynx Helicopter Operating Limit Development .” YouTube. 09 December. Accessed November 03, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bC2XIGMI2kM.