The following is a submission from guest author Eric Gomez for CIMSEC’s Distributed Lethality week.

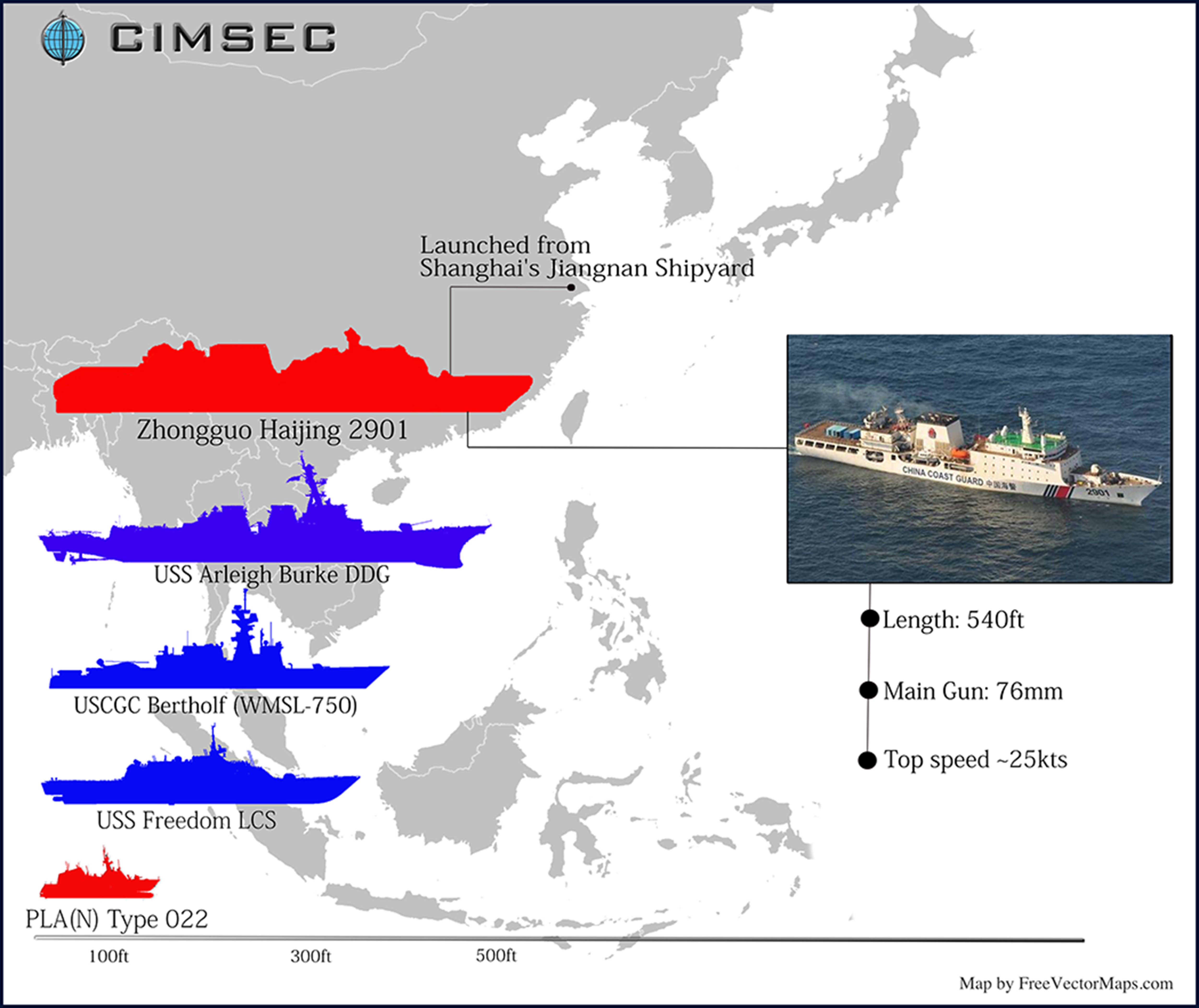

The distributed lethality concept that was unveiled in Proceedings at the start of this year represents a new way of using naval forces against an adversary attempting to deny the U.S. Navy access to a combat area. Simply put, distributed lethality calls for creating hunter-killer surface action groups (SAG) consisting of a handful of surface combatants that conduct offensive anti-submarine and anti-surface operations.

In the Western Pacific, the greatest challenges to the U.S. Navy’s surface fleet are the air, naval, and missile forces of the People’s Republic of China, which are supported by a growing array of surveillance and reconnaissance systems. However, China’s ability to track and target American surface ships is still relatively weak and could be the “Achilles’ heel” of China’s anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) strategy. Distributed lethality seeks to exploit this surveillance weakness by putting more targets into a combat area, making tracking and targeting a more complex problem.

If implemented as intended, distributed lethality will likely succeed at making it difficult for the Chinese military to target U.S. Navy surface ships that are underway. However, the ports and base facilities in the region that the Navy depends on to keep it surface forces in the fight would be at risk. For example, the naval base at Yokosuka, Japan, the only base west of Hawaii that can repair aircraft carriers, lies within the range of Chinese land-based missiles. Bases that are protected by distance from Chinese attack, such as Guam, are too far away to play a major role in the distributed lethality concept that calls for fast tempo offensive operations.

In order for distributed lethality to work, the U.S. Navy and government must start reaching out to Western Pacific partners to expand American access to naval bases and port facilities. Realistically, “expanded access” would probably look like the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement with the Philippines, or the stationing of Littoral Combat Ships in Singapore. These are not full-fledged U.S. bases, but there is an expanding American military presence that should include more of the surface combatants that are the lynchpin of distributed lethality. The best way to implement the distributed lethality concept in the Western Pacific is through distributed basing, expanding the number of facilities where U.S. surface combatants can be based.

Distributed basing gives strategic heft to the distributed lethality concept in two ways. First, distributed basing increases the credibility of American extended deterrence in the Western Pacific by creating more “tripwires” similar to the token American forces stationed in Berlin during the Cold War. Second, distributed basing raises the costs of Chinese attacks by placing U.S. surface combatants alongside the military equipment of host countries. If the Chinese military wants to inflict a crippling first strike on U.S. Navy surface combatants in port, it will risk destroying the equipment and killing the personnel of another country’s military. This would likely draw that country into military conflict with China, thereby raising the economic, political, and military costs of the Chinese decision to strike.

However, no military decision comes without negative consequences, and it is important to consider the costs or pitfalls of distributed basing. Bases and other facilities will have to be able to withstand attacks. There has been much discussion about hardening U.S. Air Force bases against Chinese missile attacks. Similar hardening efforts or installing the Aegis Ashore missile defense system would be two examples of American efforts to keep a

distributed surface combatant force alive in the opening stages of a conflict. Fully implementing such base defenses will take time and resources, both of which might be in short supply. This could create a “window of opportunity” for Chinese military action in which the distributed lethality concept will be less effective as bases and facilities are upgraded.

Additionally, there is no guarantee that other states will allow the U.S. to implement distributed basing. Even in Japan, a U.S. treaty ally, there is considerable popular opposition to the basing of American forces. An increasingly threatening China could provide a compelling rationale for allowing American warships to be put back into bases and ports, but distributed basing is by no means a political slam dunk.

The distributed lethality concept does provide a new and potentially effective way for the U.S. Navy to respond to A2/AD threats, but more work needs to be done on the logistical side. In order for distributed lethality to be most effective, U.S. surface combatants should be distributed at more locations throughout the Western Pacific. This would enable them to get to their combat areas faster and would present more targets for the Chinese to engage in the early stages of an armed conflict. However, expanding access and distributing surface combatants across more facilities in the Western Pacific will not be easy tasks. Having the U.S. Navy spread across more facilities will not be beneficial unless those facilities can be adequately defended. Bringing many facilities up to an acceptable standard of protection will require an investment of time and resources that create a “window of opportunity” for Chinese action.

Having the distributed lethality concept is a good start because it shows the Navy is thinking creatively about new ways to counter the A2/AD strategy. However, more thinking and writing on the logistics aspect of distributed lethality needs to be done in order for distributed lethality to reach its full potential.

Eric Gomez is an independent analyst and recent Master’s graduate of the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University. He is working to develop expertise in regional security issues and U.S. military strategy in East Asia, with a focus on China. Eric can be reached at [email protected].