By Sally DeBoer

Navarro, Peter. Crouching Tiger: What China’s Militarism Means for the World. New York: Prometheus Books, 2015, 335pp. $19.95.

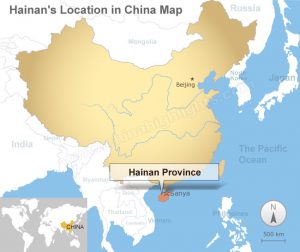

Those focused on the realm of maritime security have watched China’s actions in the East and South China Seas with some combination of fascination and trepidation over the past several years. From land reclamation efforts on Johnson South Reef to “cabbage” strategy successes around Scarborough Shoal, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has repeatedly defied convention, their neighbors’ sovereignty, and yes, international law in their expansive effort to exercise control over the seas about the first and second island chains under the guise of historical righteousness. The impending arbitration ruling from the United Nations has tensions in the region at a fever pitch. Questions abound: Will China declare an ADIZ in the South China Sea, as they did in the East China Sea in November of 2013? Will a ruling in the Philippines’ favor spur China to double down on its expansion activity and militarism? Will there be war with China, and what might such a conflict look like? It is this last question, an overarching theme in any discussion of China’s militarization and the international community’s efforts to reckon with it, that author Peter Navarro seeks to address in his book Crouching Tiger: What China’s Militarism Means for the World.

Navarro, a bestselling author and professor at the University of California Irvine’s Merge School of Business, takes a holistic and comprehensive approach to answering the question of whether or not a war with China will occur and, in the event of war, what form such a conflict might take. Perhaps most importantly, Navarro also details pathways to avoid conflict through means of diplomacy and deterrence. Navarro’s prose is engaging and moves at a rapid pace. Styled as a “geopolitical detective story,” Crouching Tiger’s text is widely accessible and consistently clear, making an issue that is opaque to most readers digestible. Each chapter begins with a multiple-choice question about the subject matter, which readers (detectives, as the book calls them) themselves are equipped to answer by its conclusion. The direct tone of the book should not be confused for simplicity, however. Navarro does not shy away from detail, addressing the complexity of great power politics head-on. Navarro’s argument is strengthened by the opinions and research of some of the world’s foremost scholars on geopolitics and China, with statements from the likes of the University of Chicago’s John Mearsheimer and the U.S. Naval War College’s Toshi Yoshihara woven throughout the text. Though short, Crouching Tiger is indeed quite dense, providing a truly sweeping account of the subject matter.

Crouching Tiger begins by setting the stage for the discussion, succinctly but completely outlining the schools of thought on great power politics, the history of China’s interactions with both the United States and the global system at large, and assessing the capabilities of the Chinese military. Navarro deftly characterizes China’s rapid military build-up in their quest for regional hegemony, covering topics from the DF-21 “carrier killer,” to China’s “Underground Great Wall” and truly staggering nuclear stockpile (this will come up again later.) Further, Crouching Tiger addresses China’s Anti-satellite (ASAT) capabilities (demonstrated famously with the destruction of the PRC’s own FY1-C weather satellite in 2007), which leave the United States’ overhead constellations, on which it has become militarily, economically, and comprehensively dependent, at risk.

Moving quickly, Navarro then delves into possible “triggers, trip wires, and flash points” that could ignite a conflict between China, the U.S., and their various allies and defense treaty cosigners. Some of these triggers will be familiar to readers who keep an eye on the news in the South China Sea, while others, such as China’s territorial disputes with India and their possible implications for coming periods of water scarcity, are less well known. In the third section of the book, Surveying the Battlefield, Navarro provides a synopsis of U.S. vulnerabilities and strategies with regard to a notional conflict. Crouching Tiger’s final sections discuss possible “pathways to peace.” In a particularly effective section, Navarro gleefully dismantles the arguments for U.S. isolationism (which seem to grow louder by the day), peace through economic engagement (which provided no guarantee of peace in World War One), and traditional nuclear deterrence a-la USSR-U.S. Cold War relations. Crouching Tiger concludes with Navarro’s own strategies to avoid conflict and ensure peace.

If Navarro can be criticized for anything, it is that Crouching Tiger lands a little on the alarmist side. But perhaps in a nation that has tolerated the squeeze of sequestration, watched its military readiness decline as the U.S. Navy rides out the last of its Reagan-era investments, and where more than one politician on either side of the aisle has promoted isolationism (either directly or by reduced investment in defense) as a sound fiscal and geopolitical policy, a little alarmism may not be a bad thing. Indeed, if Navarro’s goal in publishing Crouching Tiger is to provide a wake up call to his readers about the stark realities and implications of U.S. policy, investment, and presence in the Asia-Pacific, he has done so with considerable aplomb. The text is not lengthy; some scholars of the Asia-Pacific may find that some of Navarro’s arguments lack some context. Despite this, a broad audience will find much to consider in the pages of Crouching Tiger. As such, this book comes highly recommended to readers from the most accomplished geopolitical scholars to high-level policymakers and diplomats. I will add my voice to this chorus.

Note: There is an accompanying film series for Crouching Tiger. Find more details at Crouching Tiger’s website.

Sally DeBoer is the Book Review Coordinator for CIMSEC. She can be reached at books@cimsec.org.