By Dirk Steffen

Many suspected it as the intensity of pirate attacks off the Niger Delta increased inexorably in the course of April, with 15 attacks between 1 and 21 April 2016. There is a contest going on between those termed by the authorities as “sea criminals” and the Nigerian Navy, which is tasked to suppress them.

Situation

After a period of détente following the Nigerian general elections in April 2015, the Niger Delta is once again stirring. Former militants had made their support of the new President Muhammadu Buhari (elected in April 2015) conditional on the continued payment of “amnesty stipends” and retention of inflated security contracts. Predictably, in the face of drastically reduced oil revenue, President Buhari’s only choice was to reduce those payments, make the remainder more accountable, and let the security contracts worth hundreds of millions expire. Additionally, he went after those godfathers who had systematically abused the amnesty under the previous presidency.

The issue of a court order against the figurehead ex-militant leader Tompolo (formerly the leader of the Niger Delta insurgency in the western Niger Delta) has further stoked the flames of discontent. While Tompolo remains a fugitive, new groups and former followers vie for preeminence in replacing him within his many criminal schemes and networks, using his persecution by the government as a justifying argument.

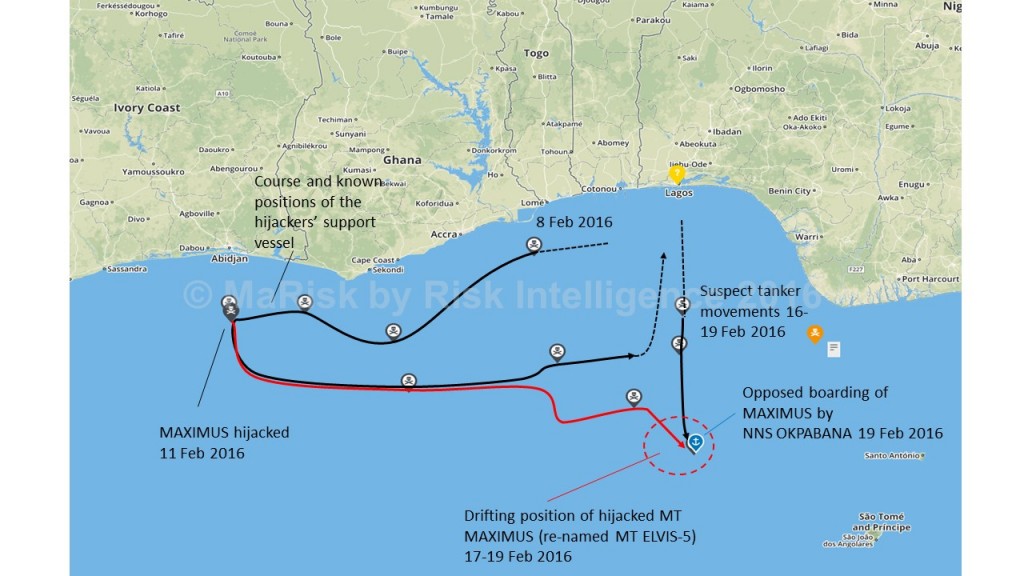

As attacks against shipping and pipelines increased in 2016, with 40 vessels attacked 74 individuals kidnapped off Nigeria alone this year as of 21 April 2016, the Nigerian Navy sprung into action. Sorties in response to attacks as well as the successful tracking and boarding of the hijacked tanker MAXIMUS (11-19 February) suggested that the Nigerian Navy was prepared to take up the challenge. Having demonstrated its effectiveness against the pirate modus operandi of hijacking product tankers in order to steal the cargo, the Nigerian Navy inadvertently redirected criminal energies to a more opportunistic and less predictable sea crime: kidnapping for ransom. This form of crime was traditionally (between 2006 and 2010) much practiced by smaller militant groups with less resources and without sponsors or patrons necessary for the more sophisticated and operationally vulnerable hijackings. Now it appears it has become a free-for-all for seaborne criminals in the Niger Delta. After a wave of inshore kidnappings in January 2016, attacks offshore the Niger Delta out to 120 nm increased throughout February and March. Virtually all of these were carried out by only speed boats without mother ship support and seem to have reached a temporary climax in April.

Challenge and Response

On 15 April 2016 the Nigerian Navy responded by launching Operation Tsare Teku (Haussa for “Protection of the Sea”) with a force consisting of NNS OKPABANA, NNS KYANWA, NNS SAGBAMA and NNS ANDONI as well as 3 other ships held in reserve. The Joint Task Force in the Niger Delta had previously banned 200 hp outboard engines – the propulsion of choice for the heavy speed boats of Niger Delta-based pirates and militants, and on 19 April the Navy impounded 26 boats equipped with such engines in Warri. On 22 April the Navy re-iterated the ban of 200 hp engines.

Within hours a group called the Niger Delta Avengers (NDA) responded to these actions. The NDA had already claimed responsibility for the hijacking of the tanker LEON DIAS on 29-31 January and the subsequent kidnapping of 5 crew members. They also claimed responsibility for a number of attacks on pipelines including the Forcados export pipeline in February 2016. In a statement issued on 22 April they finally threw down the gauntlet:

“We are hereby calling on the Nigerian Navy to desist from such unlawful acts and recede the call for the ban on 200HP outboard engines as refusal to heed this warning of ours will spun us to declare a war on the Nigerian Naval Force. This war will aide us achieve nothing but expose the Nigerian Navy to the biggest embarrassment in the history of the force. It is also a promise from us that we shall make the waterways unsafe for any vessel or petroleum tanker if you fails to listen to our warning and still go about harassing and killing our people in the guise of escorting vessels along the Niger Delta creeks.”

The NDA are most likely a “mouthpiece” for a yet unorganised number of armed groups in the Niger Delta, but that makes them no less of a concern. Like the Movement of the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) they may quickly turn into a rally point in case of an exaggerated military backlash. This presents the Nigerian Navy with a conundrum: while the suppression of acts of piracy falls squarely into the Navy’s remit, they have in fact inherited a legacy problem for which they are not well prepared.

Capabilities and limitations of the Nigerian Navy

The focus of Nigerian Navy operations since 2006 has been the fight against insurgents (between 2006 and 2009) and against illegal bunkering on the creeks and rivers of the Niger Delta. The Navy forms part of the inter-agency Joint Task Force who currently prosecute a riverine campaign called Pulo Shield in the Niger Delta. For reasons of prestige, both the Navy and the Nigerian Maritime Safety Agency (NIMASA) have long downplayed or denied the threat of piracy in Nigerian waters, engaging in semantic games that re-defined piracy (legally correct, but misleading) as “armed robbery” inside territorial waters or as “community issues.” At international and regional conferences, the previous Director General of NIMASA, Patrick Ziakede Akpolobokemi (now indicted for fraud along with his associate Tompolo), routinely grandstanded about Gulf of Guinea piracy without even uttering the word “Nigeria.”

The result is a Nigerian Navy that is geared towards riverine law enforcement operations, but that lacks a credible coastal enforcement capability in spite of recent acquisitions of four Offshore Patrol Vessels in 2015 (NNS OKPABANA, NNS CENTENARY, NNS SAGBAMA, NNS PROSPERITY) and measurable increases in tactical proficiency. The Achilles heel is the lack of true Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA), insufficiently networked assets and ineffective command centers. The territorial organization into Western, Central and Easten Naval Command is suitable for riverine operations, but less so for the centralized approach required for MDA and counterpiracy.

The Nigerian Navy is also heavy on shore-side organisztion, draining resources away from the fleet. Many small and medium-sized Nigerian Navy patrol boats are idle due to lack of spares, crews, and fuel. An investigation has been launched into the Navy’s past lopsided procurement practices, but in the current situation, this only adds insult to injury. From a material point of view, the Nigerian Navy’s situation has been dire for a long time. In August 2015 the new Chief of Naval Staff Vice-Admiral Ibok-Ete Ekwe Ibas conceded that “the Nigerian Navy [… ] is unable to fulfill its constitutional obligation of defending and protecting the country’s territorial waters because more than half its fleet is broken down.”

A more or less permanent presence at sea by the Nigerian Navy is provided only by those patrol boats providing oil field security – contracted to private companies, but manned mostly by Nigerian Navy personnel. Under a Memorandum of Understanding between these security companies and the Navy, the patrol boats should remain available for “national security” purposes and share MDA information with the Navy. Contracted escort vessels have been detached from their commercial duties in the past to intervene in ongoing pirate attacks, but the reality is this arrangement deprives the Nigerian Navy of operational reserves and flexibility – such as would be necessary for an operation like Tsare Teku.

Operation Tsare Teku

Of the four vessels now assigned to Tsare Teku only OKPABANA and SAGBAMA can provide meaningful surveillance and pursuit capabilities. KYANWA is an elderly buoy tender (ex-USCGC SEDGE, WLB-402 – laid down in 1943) with a top speed of 12 knots and ANDONI is a locally built patrol boat with only standard sensors and a top speed of 21 knots. Only OKPABANA has a helicopter flight deck, but no organic helicopter. As in the MAXIMUS case, the Nigerian Navy would rely on the two Air Force ATR-42 Maritime Patrol and Reconnaissance Aircraft for aerial reconnaissance. However, both aircraft are stationed in the north of Nigeria where they take part in the campaign against Boko Haram.

Three more vessels are slated to join the operation: NNS CENTENARY, NNS BURUTU and NNS ZARIA. Of those three only the recently acquired CENTENARY has a helicopter flight deck and an above average command and communications suite. BURUTU and ZARIA are both Singapore-built fast patrol craft that are suitable for EEZ patrolling and would be a valuable addition as fast responders – provided they join the effort.

Effectively, thus, the current offshore surveillance and deterrence element of Tsare Teku relies almost entirely on NNS OKPABANA, a former US Coast Guard HAMILTON-class cutter (ex-USCGC GALLATIN, WHEC-721) that has been in near constant use responding to incidents since January and taking part in the AFRICOM exercise OBANGAME EXPRESS/SAHARAN EXPRESS 2016 as one of the mainstays of the Nigerian Navy. The 48-year old vessel is now increasingly struggling with mechanical problems.

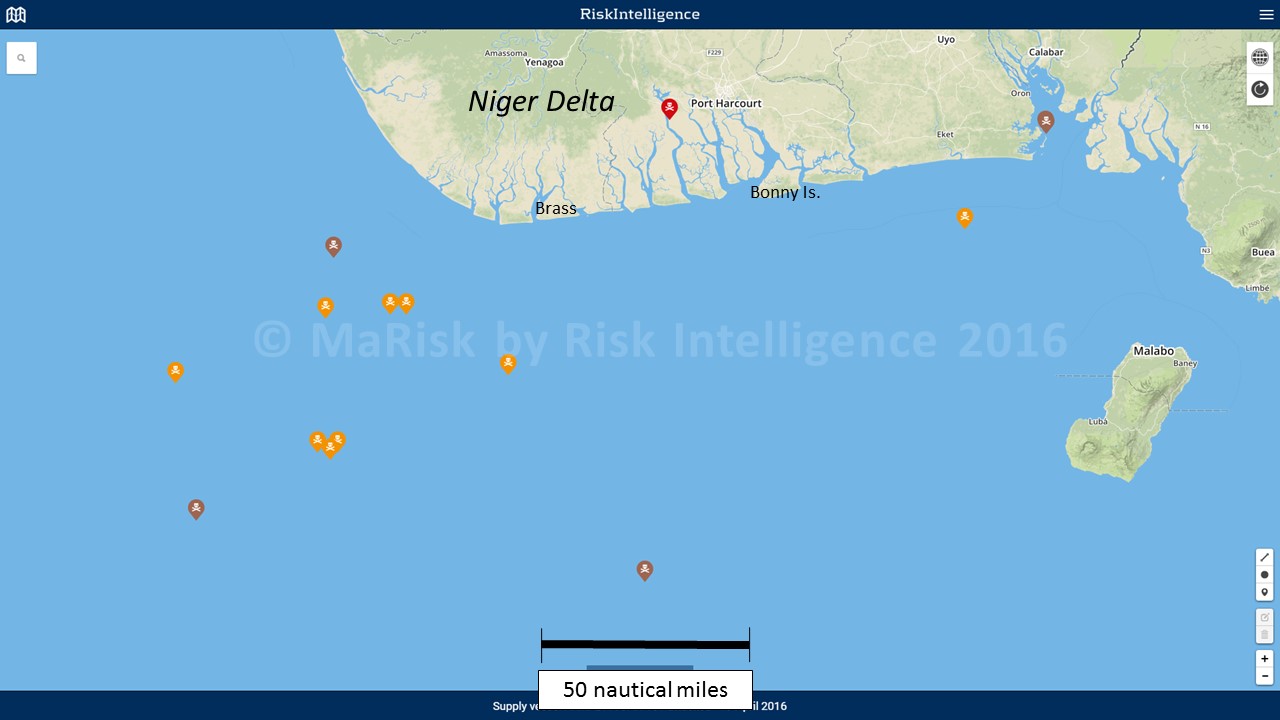

Wisely, the Nigerian Navy has therefore geographically limited the objective of Tsare Teku to what Ibas identified as the two major “hot spots” of pirate activity: the sea area off Brass (located on the southwestern tip of the Niger Delta in Bayelsa state) and off Bonny (the entrance to the sea ports of Onne and Port Harcourt in Rivers state on the south coast of the Niger Delta). While the Bonny area will be relatively easy to secure due to the converging traffic and proximity of pirate attacks to the Bonny River Fairway Buoy, pirate attacks off Bayelsa have been more dispersed and out to 120 nautical miles from the coast – often at night. This will present a challenge and attacks on Chevron’s Agbami oil field on 7 and 10 April show that the criminals have little respect for a weak naval presence. On 7 April, two tankers waiting to load at the terminal were attacked. NNS OKPABANA responded and was in the field on 7/8 April. However, just 2 days later, pirates attacked another tanker in the same location. Ultimately, it fell to the field security vessel to provide a timely response.

Outlook

Attacks have abated since 21 April, but the cyclical, or surge-like, nature of attacks is typical for Niger Delta offshore violence. A number of hostages have been released over the past few days and more will be freed in the near future. All other things remaining equal, once the funds generated from the ransoms have been distributed and loyalties assured, a resumption of attacks should be expected.

In the short term all the Nigerian Navy will be able to provide is a sticking plaster. Just like in Somalia, the problem will not be resolved at sea. However, unlike Somalia, Nigeria actually has the sovereign power (and increasing political will, it seems) to address both the symptoms and the causes on shore. The control of inshore waterways and community engagement will form a part of the ongoing operation Tsare Teku. However, its success will also depend on the Nigerian Navy getting its own house in order. Ibas pointed out in 2015 “that most of the operations designed to eradicate the oil bunkering syndicates operating in the country’s waters were still achieving limited success because some navy officers and other security personnel were involved in the illegal activities.”

From an operational point of view, the best course of action for the Nigerian Navy in the short term (apart from a joint effort ashore) would be to fold the contracted field security and patrol vessels into a comprehensive scheme for merchant vessel protection, rather than allowing a large number of these vessels to be absorbed into one-on-one escort/security missions or “waiting for business.” This would not necessarily clash with commercial interests of oil companies operating convoys to and from their offshore installations. The idea here could be to coordinate and promulgate convoy schedules and open them for general shipping (much like the “national” convoys in the Gulf of Aden became open to ships flying all flags), thus maximizing the efficiency of existing operational naval vessels. Corridors could be extended in some cases or linked using other Nigerian Navy vessels or by sharing contracted patrol boats. This would have the added benefit of enabling the contracted patrol boats to pursue and apprehend attackers under the Nigerian Navy’s Rules of Engagement rather than having to remain purely defensive in accordance with the more restrictive Standard Operating Procedures of private security companies, which only allow a defensive posture.

Searching, sweeping, and deterrence patrols are likely to produce minimal results given the fleeting nature of the threat, the size of sea area, and the complexity of the Niger Delta coastline. Instead, the most valuable assets – like OKPABANA, CENTENARY, and the Sea Eagle fast patrol craft should be held in readiness as fast response assets. The low number and limited response radius of the vessels (for as long as the OPVs do not routinely operate helicopters on their missions) would probably not make it efficient to use them “on station” in the transit corridors in the way this was done in the Gulf of Aden. Continuous sea time would also aggravate the already precarious maintenance issues of some vessels.

In summary: the Nigerian Navy will be on the defensive in the short term for whatever comes at it from the creeks of the Niger Delta. This is not as ignominious as it sounds since command of the sea (however limited in geographic scope) is by definition a defensive strategic objective. Initially however, the Nigerian Navy will also contend with serious constraints ranging from a lack of awareness of what plays out in Nigerian waters outside the coverage of coastal radar stations and the Automated Identification System (AIS), as well as insufficient assets (or readiness of those assets) to effectively police the offshore littoral. The Nigerian Navy, even if it wishes to engage the merchant marine – as recently suggested by Vice-Admiral Ibas, will not initially benefit from the support of the merchant marine. Past experiences of naval officers’ connivance with criminals, corruption, extortion, and bullying at the hands of the Nigerian Navy have undermined industry’s trust in the Nigerian Navy. It will take time and fence-mending to reassure the international shipping community so that they will provide the indispensable data the Nigerian Navy would need in order to maintain MDA and effectively co-ordinate shipping in a piracy-threat area. Until then, operations like Tsare Teku will be largely symbolic. It may make life a little more complicated for the pirates, but not unduly so in the foreseeable future.

Dirk Steffen is a Commander (senior grade) in the German Naval Reserve with 12 years of active service between 1988 and 2000. He took part in the African Partnership Station exercises OBANGAME EXPRESS 2014, 2015 and 2016 at sea and ashore for the boarding-team training and as a Liaison Naval Officer on the exercise staff. He is normally Director Maritime Security at Risk Intelligence (Denmark) when not on loan to the German Navy. He has been covering the Gulf of Guinea as a consultant and analyst since 2004. The opinions expressed in this article are his alone, and do not represent those of any German military or governmental institutions.

Featured Image: NNS KYANWA alongside NNS THUNDER at Apapa Naval base (Lagos) in 2014. Photo: Dirk Steffen