By CAPT Chris Rawley and LCDR Cedric Patmon

Technology adoption moves in fits and starts. The developing world cannot be forced into accepting new technology, but it can be enabled, and often in a surprising manner. A recent example is the leap in communications technology. During the 20th Century most of the world developed a robust network of terrestrial-based telecommunications based primarily on the ubiquitous land-line telephone system. Without this infrastructure in place Sub-Saharan African countries were largely left behind at the start of the information revolution. But at the turn of the new century something interesting happened. Rather than retroactively building an archaic phone system Africans embraced mobile phone technology. From 1999 through 2004 the number of mobile subscribers in Africa eclipsed those of other continents, increasing at a rate of 58 percent annually. Asia, the second fastest area of saturation, grew at only 34 percent during that time. The explosive growth of mobile phones and more recently smart phones across practically every African city and village has liberated economies and facilitated the free flow of information. This technology also enabled Africans to lead the world in mobile money payment solutions, bypassing increasingly obsolete banking systems.

Today, Africans have another opportunity to leap ahead in technology to protect one of their most important areas of commerce – their coastal seas. Africa’s maritime economy is absolutely critical to the continent’s growth and prosperity during the next few decades. On the edge of the Eastern Atlantic the Gulf of Guinea is bordered by eight West African nations, and is an extremely important economic driver. More than 450 million Africans derive commercial benefit from this body of water. The region contains 50.4 billion barrels of proven petroleum reserves and has produced up to 5.5 million barrels of oil per day. Additionally, over 90 percent of foreign imports and exports cross the Gulf of Guinea making it the region’s key connector to the global economy.

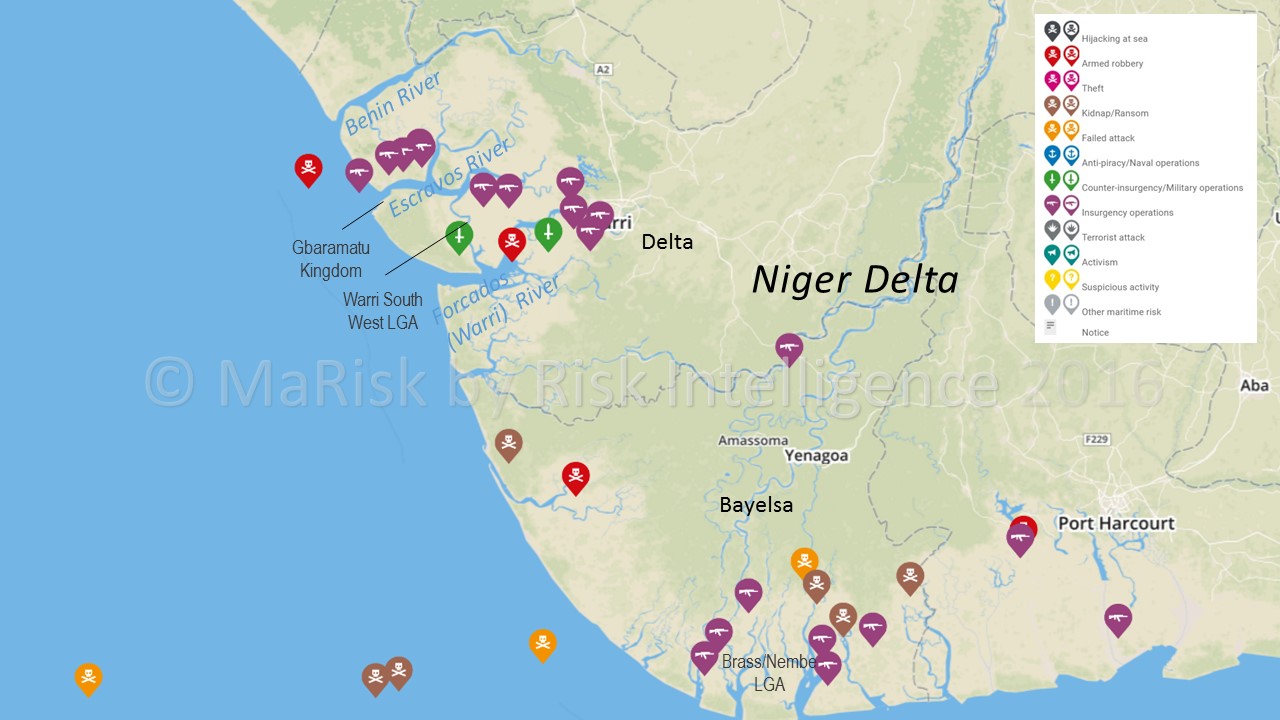

Favorable demographics and industrious populations put coastal Africans in a position to prosper, but an increase in illegal fishing activities and piracy since the early 2000s has severely impeded this potential. The growth in acts of piracy and armed robbery at sea in the Gulf of Guinea from 2000 onward points to the challenges faced by West African states.

According to Quartz Africa, illegal fishing activities in the region have a negative economic impact of $2-3 billion annually. “Fish stocks are not restricted to national boundaries, and that is why the solutions to end the overfishing of West Africa’s waters can only come from joint efforts between the countries of the region,” Ahmed Diame, Greenpeace’s Africa Oceans campaigner, said in a statement. Marine pollution, human, and narcotics trafficking are also major issues facing the region.

Due to the economic impact of illicit activities in and around West Africa a Summit of the Gulf of Guinea heads of state and government was held in 2013 in Yaoundé, Cameroon. This resulted in the adoption of the Yaoundé Declaration on Gulf of Guinea Security. Two key resolutions contained in the Declaration were the creation of an inter-regional Coordination Centre on Maritime Safety and Security for Central and West Africa, headquartered in Yaoundé, and the implementation of a new Code of Conduct Concerning the Prevention and Repression of Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships, and Illegal Maritime Activities in West and Central Africa. Adoption of this agreement has laid the foundation for critical information sharing and resource cooperation that can be used to combat piracy, illegal fishing, and other illicit activities in the Gulf of Guinea.

Though the Code of Conduct established an architecture for maritime security in the region, without enforcement on the water, diplomatic efforts are largely impotent. Key to enforcement is the ability to identify, track, and prosecute nefarious actors on the high seas and in coastal areas. So-called maritime domain awareness is gradually improving in the area, but current options for maritime surveillance are limited. The largest local navies have offshore patrol vessels capable of multi-day over-the-horizon operations, but even these vessels have limited enforcement capacity. Patrol vessels face maintenance issues and fuel scarcity. Shore-based radar systems at best reach out 30 or 40 nautical miles, but are plagued by power and maintenance issues. Moreover, a shore-based radar, even with signals correlated from vessels transmitting on the Automatic Identification System, only provides knowledge that a contact is afloat, not necessarily any evidence to illicit actions.

Latin American navies face similar maritime challenges to those in Africa and have learned that airborne surveillance is simply the best way to locate, track, identify, and classify surface maritime targets involved in illicit or illegal activity. A retired senior naval officer from the region related a study in the Caribbean narcotics transit zone to one of the authors that compared different surveillance mechanisms for the 11,000 square nautical mile area. The probability of detecting a surface target within six hours rose from only five percent with a surface asset to 95 percent when maritime patrol aircraft were included. Only a handful of coastal African countries have fixed-wing maritime patrol aircraft and helicopters, but these aircraft face similar issues to surface assets with fuel costs and mechanical readiness resulting in limited flight time on station.

Drone Solutions to African Maritime Insecurity

Unmanned aerial systems (UAS), or drones, as they are known colloquially, provide a way for African navies and coast guards to greatly enhance maritime security in a relatively inexpensive manner, similar to the ways mobile telephony revolutionized communications on the continent. Similar to the evolution of computing power outlined by Moore’s law tactical UAS are rapidly growing in capabilities while decreasing in cost. Improvements in sensors, endurance, and payload are advancing quickly. For any solution, acquisition cost, maintainability, and infrastructure required are key factors to be considered. The cost per flying hour of most UAS is negligible compared to their manned counterparts. Today’s fixed and rotary-wing systems, whether specifically designed for military use or for commercial applications, can be adapted for surveillance in a maritime environment without much additional cost.

Because each country has unique requirements and budgets no single UAS solution is appropriate. Maritime drones can be based ashore or on coastal patrol vessels. One viable option for countries with limited resources involves services contracted by Western Partners, a model which has already been proven in the region for other applications. Alternatively, the Yaoundé Code of Conduct provides a framework for a possible shared model. This agreement can provide the timely sharing of critical information ascertained by maritime surveillance and reconnaissance systems to aid in the enforcement of the maritime laws and agreements in the region. Contractor-operated drones could be allocated across countries by leadership in the five Zones delineated by the Code. Multinational cooperation on maritime security has already been tested in the annual Obangame Express exercise and during real-world counterpiracy operations. Understanding that not all countries have the investment capability to purchase their own stand-alone systems, consideration could be given to sharing the initial investment costs between countries. The logistics of system placement and asset availability would have to be determined by the participating countries themselves but the benefit of such a program would positively impact the entire region economically, enhance interoperability, and assist in regional stability.

Drones are already being operated across Africa by Africans. Zambia recently purchased Hermes 450 unmanned aerial vehicles for counter-poaching operations. There are also African unmanned systems flying surveillance missions over areas plagued by violent extremists groups. UAS are even being used to transport blood and medical supplies across the continent’s vast rural landscapes. Shifting these assets over water is a natural progression. One concern about using UAS is airspace deconfliction. However, this problem is minimized because there is little to no civil aviation in most parts of Africa. Additionally, most maritime UAS would be flying primarily at low altitudes over water from coastal bases.

Conclusion

The leap-ahead capabilities that unmanned surveillance aircraft could provide to coastal security around Africa are clearly evident. African navies with adequate resources should make acquisition of unmanned air systems a priority. Likewise, western foreign military assistance programs should focus on providing contracted or organic unmanned aircraft capabilities.

Captain Rawley, a surface warfare officer, and Lieutenant Commander Patmon, a naval aviator, are assigned to the U.S. Navy’s Sixth Fleet’s Maritime Partnership Program detachment responsible for helping West African countries enhance their maritime security. The opinions in this article are those of the authors alone and do not officially represent the U.S. Navy or any other organization

Featured Image: GULF OF GUINEA (March 26, 2018) A visit board search and seizure team member from the Ghanaian special boat service communicates with his team during a search aboard a target vessel during exercise Obangame Express 2018, March 26. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Theron J. Godbold/Released)