By Elsa B. Kania

As the South China Sea dispute continues to command headlines, such issues as China’s island building, U.S. Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS), and the contested arbitration have received justified attention, but a concurrent trend in the activities of the PLA Navy (PLAN) in the South China Sea also merits closer consideration. Within the past several months, the PLAN’s South Sea Fleet (南海舰队) has engaged in relatively sophisticated anti-submarine warfare (ASW) drills (反潜作战演练). Historically, China has remained relatively weak in ASW and continues “to lack either a robust coastal or deep-water anti-submarine warfare capability,” according to the Department of Defense.1 Despite such persistent shortcomings, the apparent advances in the realism and complexity of these recent drills suggest that the PLAN’s ASW capabilities could be progressing. Given the context, these drills, which were reported upon in detail in official PLA media,2 might also have been intended as a signaling mechanism at a time of heightened regional tension. Presumably, the PLAN is also motivated by concerns about U.S. submarines operating in the region and the submarines procured by multiple Southeast Asian nations, including rival claimant Vietnam.

While China’s ongoing investments in ASW platforms have indicated an increased prioritization of improving its ASW capabilities, the PLAN’s ability to advance in this regard will also be influenced by its level of training and experience.3 Certainly, the levels of stealth and sophistication of current and future U.S. submarines will continue to pose a considerable challenge. Although the PLAN’s ASW capabilities will likely remain limited in the short term, its attempts to realize advances in ASW reflect a new aspect of its efforts to become a maritime power and attempt to achieve “command of the sea” (制海权) within the first island chain.4

Recent PLAN ASW Drills in the South China Sea

Between May 25th and 26th, the PLAN’s South Sea Fleet engaged in ASW drills that involved a confrontation between Red and Blue Forces that continued “successively for twenty-four hours uninterrupted.”5 After entering the South China Sea through the Bashi Channel, within the Luzon Strait between Taiwan and the Philippines, the far sea training formation involved initiated the drill “under actual combat conditions.”6 The Red Force involved four surface warships, two Type 052D guided-missile destroyers (Hefei and Guangzhou), a Type 052C destroyer (Lanzhou), and a Type 054A guided-missile frigate (Yulin), as well as three unspecified anti-submarine helicopters, against a Blue Force with an unknown number of submarines.

Since anti-submarine operations have reportedly become a “key emphasis” (重点) for the South Sea Fleet, this constituted an attempt to design a more advanced, realistic drill for ASW operations.7 It was characterized as “really rare” given the large size of the search area (1,000 square nautical miles); the multiple forms of anti-submarine forces included; the multiple ASW methods used, including five kinds of sonar; the employment of a greater number of anti-submarine attack weapons including anti-submarine rockets, depth charges, and torpedoes, and finally the length of the drill, which occurred for 24 hours continuously.8 That these aspects of the drill were considered so notable implies that prior drills were appreciably less sophisticated.

Although the drill seemed somewhat more advanced than previous such exercises, PLA media commentary also highlighted the existing shortcomings in the PLAN’s ASW capabilities that the drill was intended to mitigate. According to one PLAN officer who had participated, difficulties included the command and control over and coordination among the forces involved. He also highlighted that the two forces had not established a set program or plan prior to the drill – implying that past drills had been organized around more of a “script” (脚本).9 This lack of a script enabled the whole process to “break through into actual combat confrontation” and “explore anti-submarine methods and approaches.”10 In particular, this realistic training was intended to address certain “important difficulties,” including coordination between ships and aircraft, coordination of firepower, and information-sharing.11 For instance, a Blue Force submarine engaged in evasive measures, such that the Red Force had to cooperate closely and engage in real-time information sharing to locate it again and enable the launching of “precision strikes” against it.12

Although it is difficult to compare this ASW drill to previous iterations qualitatively or quantitatively – given the limitations of available information and uncertainties about the consistency of open-source reporting on such training – a review of prior accounts of the PLAN’s ASW exercises suggests that these drills have advanced considerably within the past several years. There seemingly has been a shift in the PLAN’s ASW training, starting from relatively routine exercises held only annually in the South China Sea, towards these more advanced exercises. In this regard, the South Sea Fleet’s engagement in this ASW drill at a time of heightened tension in the South China Sea not only might have been intended to serve as a signaling mechanism, but also may have reflected a longer-term trend toward advances in the PLAN’s ASW training. In the past several years, the PLAN’s ASW drills in the South China Sea have included the following:

- September 2013: In accordance with the PLAN’s annual training plan, the East Sea Fleet held training exercises in the South China Sea that involved unspecified “new type” submarines, with collaboration between anti-submarine ships and anti-submarine helicopters, which reportedly “effectively increased ASW capability under informationized conditions.”13

- September 2014: In accordance with the PLAN’s annual training plan, the East Sea Fleet held training exercises in the South China Sea in which there was an emphasis on “testing and exploring anti-submarine tactics.”14

- May 2015: The Sino-Russian “Joint Sea” exercise incorporated an ASW component.15

- November 2015: The North Sea, South Sea, and East Sea Fleets all engaged in live-fire “confrontation drills” in the South China Sea, involving Blue and Red Forces, which emphasized “information systems of systems ASW capability.”16, 17

- January 2016: PLAN exercises with the Pakistan Navy incorporated ASW for the first time.18

- May 2016: A sophisticated, realistic drill involving the South Sea Fleet occurred in the South China Sea, as described in detail above.19

- July 2016: The PLAN’s extensive exercises in the South China Sea, which involved all three fleets, also included an ASW component.20, 21

While the list above is probably not comprehensive, this sequence seems to illustrate a potential shift in the pattern of the PLAN’s ASW training – or, at least, in official PLA media reporting on these drills. From late 2015 to the present, the reported drills have not occurred in accordance with the prior training schedule and have often involved the South Sea Fleet or multiple fleets. Perhaps this change indicates a shift in focus towards advancing the operational ASW capabilities of the South Sea Fleet in particular. As this timeframe has aligned with heightened regional tensions, the organization of such drills and the reporting on them could have indicated an increased degree of discomfort with the potential intensification of U.S. submarine activity in the South China Sea and also the ongoing procurement of Kilo-class submarines by rival claimant Vietnam, which received its fifth of six submarines in February 2016.22, 23 Eventually, this focus on realistic, unscripted ASW drills could enable the PLAN to progress in capitalizing upon the more advanced ASW platforms that have been concurrently introduced.

Ongoing Investments to Overcome Traditional Weaknesses in ASW

Although the PLAN’s ASW capabilities have historically been lacking, the increased frequency and sophistication of ASW drills have corresponded with investments in and the commissioning of new ASW platforms within the past several years. The PLAN previously had only the Ka-28 and the Z-9C as ASW helicopters, but has introduced the more sophisticated Changhe Z-18F ASW variant.24 Notably, the Y-8FQ Gaoxin-6, an anti-submarine patrol aircraft reportedly analogous to the P-3C, which has a lengthy magnetic anomaly detector, was introduced into the PLAN in 2015.25 Although it was not reported to have participated in recent exercises, the Gaoxin-6 could critically contribute to China’s future ASW capabilities. In June 2016, the PLAN’s South Sea Fleet also commissioned the Type 056A corvette Qujing, the tenth such vessel assigned to it, which reportedly has “good stealth performance” and has been upgraded with a towed array sonar for ASW.26, 27 As of 2016, a total of twenty-six Type 056 corvettes are in service throughout the PLAN, and there might eventually be sixty or more, likely including quite a few of this ASW variant.27

Beyond these existing platforms, the PLAN has been investing in multiple aspects of its ASW capability that could have significant long-term dividends. According to one assessment, the construction of a helicopter base on reclaimed land on Duncan Island in the Paracels could constitute a component of a future network of helicopter bases that would enable the PLA’s ASW helicopters to operate more effectively in those contested waters.29 The PLA’s existing and future aircraft carriers could launch multiple anti-submarine aircraft, and less-authoritative Chinese media sources have emphasized the expected efficacy of a future Chinese carrier strike group in ASW.30, 31 Concurrently, China has been establishing an underwater system of ocean floor acoustic arrays in the near seas, referred to as the “Underwater Great Wall Project” by the China State Shipbuilding Corporation responsible for its construction.32, 33 In addition, the PLAN clearly recognizes the relevance of unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) in ASW. For instance, PLA academics from China’s National Defense University characterize “unmanned operations at sea” as among today’s “important development trends.”34 There are multiple Chinese USVs and UUVs under development,34 and PLA-affiliated individuals and institutes have evidently engaged in extensive research on the topic.36

Conclusion

Although the operational potential associated with such investments might require years to be actualized, China could eventually become a significant ASW force in the South China Sea and beyond. While the PLAN’s ability to engage effectively in ASW will likely remain limited by persistent shortcomings and its relative lack of experience for the short term, it is nonetheless notable that the PLAN has evidently decided to compete in an area of traditional U.S. advantage, which had previously seemed to be a lower priority for it. These apparent advances in its ASW drills and increased investment in a variety of ASW platforms could allow the PLAN to become an inconvenience and eventually an impediment to the ability of other regional players, and perhaps even U.S. submarines, to operate unchallenged in the South China Sea. Thus far, the PLAN appears to be focusing primarily on near seas ASW, especially with the “Underwater Great Wall,” and this concern regarding defense within the first island chain could reflect a reaction to the intensified U.S. focus on submarines as a tool to counter China’s A2/AD capabilities.37

This undersea dimension of strategic competition will likely continue to be a priority for the U.S. and China alike, and the South China Sea will remain of unique strategic importance. Notably, the majority of China’s submarines, including its SSBNs, is based on Hainan Island and would probably transit to the Pacific through the South China Sea.38 While the prevailing “undersea balance” seems unlikely to change significantly in the near future,39 the PLAN’s undersea warfare capabilities could advance more rapidly than anticipated across multiple dimensions. For instance, by one assessment, China’s new Type 093B SSN could be stealthier than expected.40 Looking forward, the traditional dynamics could also be appreciably altered by technological change. In particular, the U.S. and China’s parallel advances in unmanned systems, which will likely play a significant role in future undersea warfare, could accelerate competition in this domain. While visiting the USS John C. Stennis in the South China Sea, Secretary of Defense Carter alluded to the Pentagon’s investment in “new undersea drones in multiple sizes and diverse payloads that can, importantly, operate in shallow water, where manned submarines cannot,” which could become operational within the next several years.41 The PLAN’s USVs and UUVs might not be far behind. Although the PLAN may prove unable to overcome the U.S. Navy’s undersea dominance beyond the first island chain, the South China Sea itself could become a zone of “contested command” and frequent undersea friction in the years to come.42

Elsa Kania is a recent graduate of Harvard College and currently works as an analyst at Long Term Strategy Group.

Endnotes

1. Department of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2016,” April 26, 2016, http://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2016 China Military Power Report.pdf. For prior assessments of China’s relative weaknesses and gradual advances in anti-submarine warfare, see, for instance: Stratfor, “China: Closing the Gap in Anti-Submarine Warfare,” July 20, 2015.

2. See the PLA articles referenced later in the article, including: Li Youtao [黎友陶] and Dong Zhaohui [董兆辉], “The South Sea Fleet Organized Anti-Submarine Operations Drills [Which] Continued for 24 Hours Without Interruption” [南海舰队组织反潜作战演练连续24小时不间断].

3. For reflection on the importance of training and experience in ASW, see, for instance: Lt. Cmdr. Jeff W. Benson, USN, “A New Era in Anti-Submarine Warfare,” U.S. Naval Institute, August 27, 2014, https://news.usni.org/2014/08/27/opinion-new-era-anti-submarine-warfare.

4. The objective of becoming a “maritime power” was also articulated in China’s latest defense white paper. See: Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China[中华人民共和国国防部], “China’s Military Strategy” [中国的军事战略],” May 26, 2015.

5. Li Youtao [黎友陶] and Dong Zhaohui [董兆辉], “The South Sea Fleet Organized Anti-Submarine Operations Drills [Which] Continued for 24 Hours Without Interruption” [南海舰队组织反潜作战演练连续24小时不间断], China Military Online, May 26, 2016, http://www.81.cn/jwgz/2016-05/26/content_7073486.htm.

6. Ibid.

7. “The Strongest Lineup! The South Sea Fleet’s Five Large Primary Warships Through Day and Night [Engaged in] Joint Anti-Submarine [Operations]” [最强阵容!南海舰队五大主力战舰跨昼夜联合反潜], PLA Daily, May 27, 2016, http://news.xinhuanet.com/mil/2016-05/27/c_129019813.htm.

8. Li Youtao [黎友陶] and Dong Zhaohui [董兆辉], “The South Sea Fleet Organized Anti-Submarine Operations Drills [Which] Continued for 24 Hours Without Interruption” [南海舰队组织反潜作战演练连续24小时不间断], China Military Online, May 26, 2016, http://www.81.cn/jwgz/2016-05/26/content_7073486.htm.

9. Ibid.

10. “The Strongest Lineup! The South Sea Fleet’s Five Large Primary Warships Through Day and Night [Engaged in] Joint Anti-Submarine [Operations]” [最强阵容!南海舰队五大主力战舰跨昼夜联合反潜], PLA Daily, May 27, 2016, http://news.xinhuanet.com/mil/2016-05/27/c_129019813.htm.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. “The East Sea Fleet’s South [China] Sea Drills Life-Fire Multiple New-Type War Mines, Successfully Destroying the Targets” [东海舰队南海演练实射多枚新型战雷成功摧毁目标], PLA Daily, September 26, 2013, http://mil.cnr.cn/jstp/201309/t20130926_513692312.html.

14. “The Navy’s East [China] Sea Fleet Organized Live-Fire Drills Under Complicated Acoustic Conditions” [海军东海舰队组织复杂水声环境下战雷实射演练], PLA Daily, September 26, 2014, http://news.xinhuanet.com/photo/2014-09/27/c_127040400.htm.

15. “China-Russia Drill Joint Anti-Submarine [Exercise]” [中俄演练联合反潜], Xinhua, August 26, 2015, http://military.people.com.cn/n/2015/0826/c1011-27518230.html.

16. “Chinese navy conducts anti-submarine confrontation drill in South China Sea,” CCTV, November 20, 2015, http://220.181.168.86/NewJsp/news.jsp?fileId=327578.

17. The Navy Held Submarine-Aircraft Confrontation Drills in a Certain Maritime Space in the South China Sea” [海军在南海某海域举行潜舰机实兵对抗演练], China Youth Daily, November 21, 2015, http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2015-11-20/doc-ifxkwaxv2563788.shtml.

18. Koh Swee Lean Collin, “China and Pakistan Join Forces Under the Sea,” National Interest, January 7, 2016, http://nationalinterest.org/feature/china-pakistan-join-forces-under-the-sea-14829

19. Li Youtao [黎友陶] and Dong Zhaohui [董兆辉], “The South Sea Fleet Organized Anti-Submarine Operations Drills [Which] Continued for 24 Hours Without Interruption” [南海舰队组织反潜作战演练连续24小时不间断], China Military Online, May 26, 2016, http://www.81.cn/jwgz/2016-05/26/content_7073486.htm.

20. “The Three Large Fleets’ Realistic Confrontation,” [三大舰队实兵对抗], China Navy Online, July 14, 2016, http://jz.chinamil.com.cn/n2014/tp/content_7154202.htm.

21. Ibid.

22. “The Fifth Russian-Made Kilo Submarine [Has Been] Consigned to Vietnam” [第五艘俄制基洛级潜艇“托运”到越南], Xinhua, March 3, 2016, http://youth.chinamil.com.cn/view/2016-03/03/content_6907855.htm.

23. Minnie Chan, “China and US in silent fight for supremacy beneath waves of South China Sea,” South China Morning Post, July 8, 2016, http://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/1985071/china-and-us-silent-fight-supremacy-beneath-waves-south.

24.“The Z-18 Anti-Submarine Helicopter [Has Been] Fitted With a New Radar [That] Can Attack Air-Independent Propulsion Submarines” [直18反潜直升机配新雷达 可攻击AIP潜艇], Sina, April 30, 2014, http://mil.news.sina.com.cn/2014-04-30/1712776972.html.

25.“Expert: “Gaoxin-6” improves China’s anti-submarine capability greatly,” China Military Online, July 10, 2015, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/Opinion/2015-07/10/content_4594293.htm.

26. “China commissions new missile frigate Qujing,” China Military Online, June 12, 2016, http://english.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/china-military-news/2016-06/12/content_7096962.htm.

27. “A New-Type Corvette Has Been Officially Delivered to the Navy” [新型护卫舰正式交付海军],Ministry of National Defense Website, February 26, 2013, http://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2013-02/26/content_2340335.htm.

28. Department of Defense, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2016,” April 26, 2016, http://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2016 China Military Power Report.pdf.

29. Victor Robert Lee, “Satellite Images: China Manufactures Land at New Sites in the Paracel Islands,” The Diplomat, February 13, 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2016/02/satellite-images-china-manufactures-land-at-new-sites-in-the-paracel-islands/.

30. “The PLA Is Building an Effective Weapon in the South [China] Sea’s Seabed Against the American Military’s Submarines” [解放军针对美军潜艇在南海海底打造利器], Sina, June 18, 2016, http://mil.news.sina.com.cn/jssd/2016-06-18/doc-ifxtfrrc3844240.shtml.

31. “Our Aircraft Carrier Fitted with an Anti-Submarine Weapon [Will] Make American and Japanese Submarines Not Rashly Dare To Draw Near” [我航母配一反潜利器 使美日潜艇不敢轻易靠近], Sina, June 29, 2016, http://mil.news.sina.com.cn/jssd/2016-06-29/doc-ifxtsatm0986174.shtml.

32. Richard D. Fisher, “China proposes ‘Underwater Great Wall’ that could erode US, Russian submarine advantages,” IHS Jane’s Defence Weekly, May 17, 2016, http://www.janes.com/article/60388/china-proposes-underwater-great-wall-that-could-erode-us-russian-submarine-advantages.

33. See also: Lyle Goldstein and Shannon Knight, “Wired for Sound in the ‘Near Seas,’” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, April 2014, http://www.theguardian.pe.ca/media-ugc/items/2014-04-28-11-39-30-Goldstein&Knight%20-%20Wired%20for%20Sound%20in%20the%20Near%20Seas%20-%20Apr14.pdf.

34. Li Daguang [李大光] and Chan Jiang [姜灿], “Unmanned Surface Vehicles Have Become a Cutting-Edge Weapon for Future Maritime Warfare,” [无人艇成未来海上新锐武器], PLA Daily, February 12, 2014, http://military.china.com.cn/2014-02/12/content_31445672.htm.

35. Jeffrey Lin and P.W. Singer, “The Great Underwater Wall of Robots,” Eastern Arsenal, June 22, 2016, http://www.popsci.com/great-underwater-wall-robots-chinese-exhibit-shows-off-sea-drones.

36. For instance, Jiao Anlong [焦安龙],“An Exploration of Unmanned Anti-Submarine Warfare Platforms Under Informationized Conditions” [信息化条件下无人反潜作战平台探析], Science and Technology Horizons, (33), pp. 403-404, http://www.cqvip.com/qk/70356a/201333/48101887.html.

37. See, for instance: Megan Eckstein, “CNO Richardson: Navy Needs Distributed Force Of Networked Ships, Subs To Counter A2/AD Threat,” USNI News, March 11, 2016, https://news.usni.org/2016/03/11/cno-richardson-navy-needs-distributed-force-of-networked-ships-subs-to-counter-a2ad-threat.

38. For recent commentary on the topic, see, for instance: Minnie Chan, “South China Sea air strips’ main role is ‘to defend Hainan nuclear submarine base,’” South China Morning Post, July 23, 2016, http://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacydefence/article/1993754/southchinaseaairstripsmainroledefendhainan.

39. For a more detailed consideration of the undersea balance, see: Owen Cote, “Assessing the Undersea Balance Between the U.S. and China,” SSP Working Paper, February 2011.

40. Dave Majumdar, “Why the US Navy Should Fear China’s New 093B Nuclear Attack Submarine,” National Interest, June 27, 2016, http://nationalinterest.org/blog/thebuzz/whytheusnavyshouldfearchinasnew093bnuclearattack16741 .

41. Geoff Dyer, “U.S. to sail submarine drones in South China Sea,” Financial Times, April 18, http://www.cnbc.com/2016/04/18/us-to-sail-submarine-drones-in-south-china-sea.html.

42. This term is taken from: Bernard Brodie, A Layman’s Guide to Naval Strategy, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.: 1942.

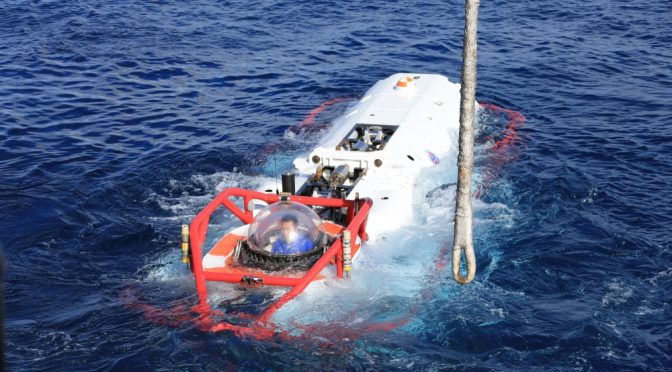

Featured Image: PACIFIC OCEAN (July 13, 2016) A sailor from the Chinese navy submarine rescue ship Changdao (867) sits in an LR-7 submersible undersea rescue vehicle off the coast of Hawaii following a successful mating evolution between the LR-7 and a U.S. faux-NATO rescue seat laid by USNS Safeguard (T-ARS-50), during Rim of the Pacific 2016. The evolution was the final event and practical portion of a multinational submarine rescue exercise between seven countries. (Chinese navy photo by Kaiqiang Li)