Pitch Your Capability Topic Week

By Tyler Totten

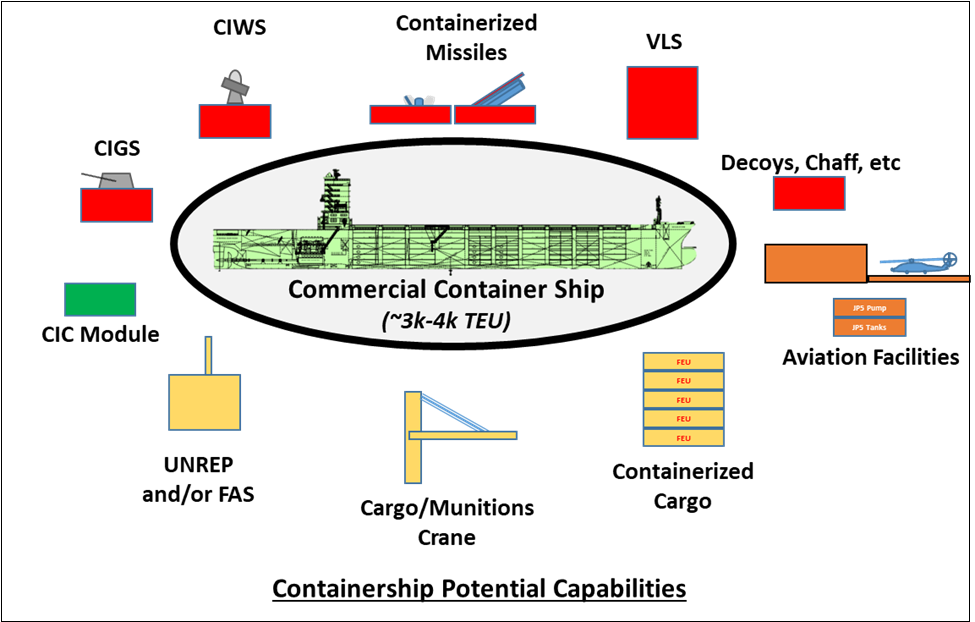

The U.S. Navy should pursue commercial containerships and compatible containerized mission systems. These ships and systems will allow the U.S. Navy to rapidly field new technologies, expand the maritime industrial base, grow the ranks of experienced seafarers, and provide surge capacity in times of national need. Containerships, as well as combination containership/roll-on roll-off vessels (ConRo), would allow the U.S. Navy to affordably procure a large number of hulls compared to typical naval warships, and open options to augment a range of missions. These ships would allow conventional combatants to focus their high-end capabilities on the highest priority missions, while augmenting many of their capabilities with containerized support. Containerships can act as valuable force multipliers and retain a significant amount of modularity in a time when conventional naval force structure is at risk of falling behind the rapidly evolving state of capability.

Containership Capabilities and Modularity

Because even a relatively large mission payload would still be a small fraction of a containership’s capacity, there would be plenty of space for systems that feature typically inefficient form factors. Relieved of the need for the most optimal and efficient space and weight arrangements, there are options for affordability and capability that might otherwise be challenging on a conventional combatant where weight, volume, and complexity are highly constrained and deeply embedded into the hull design.

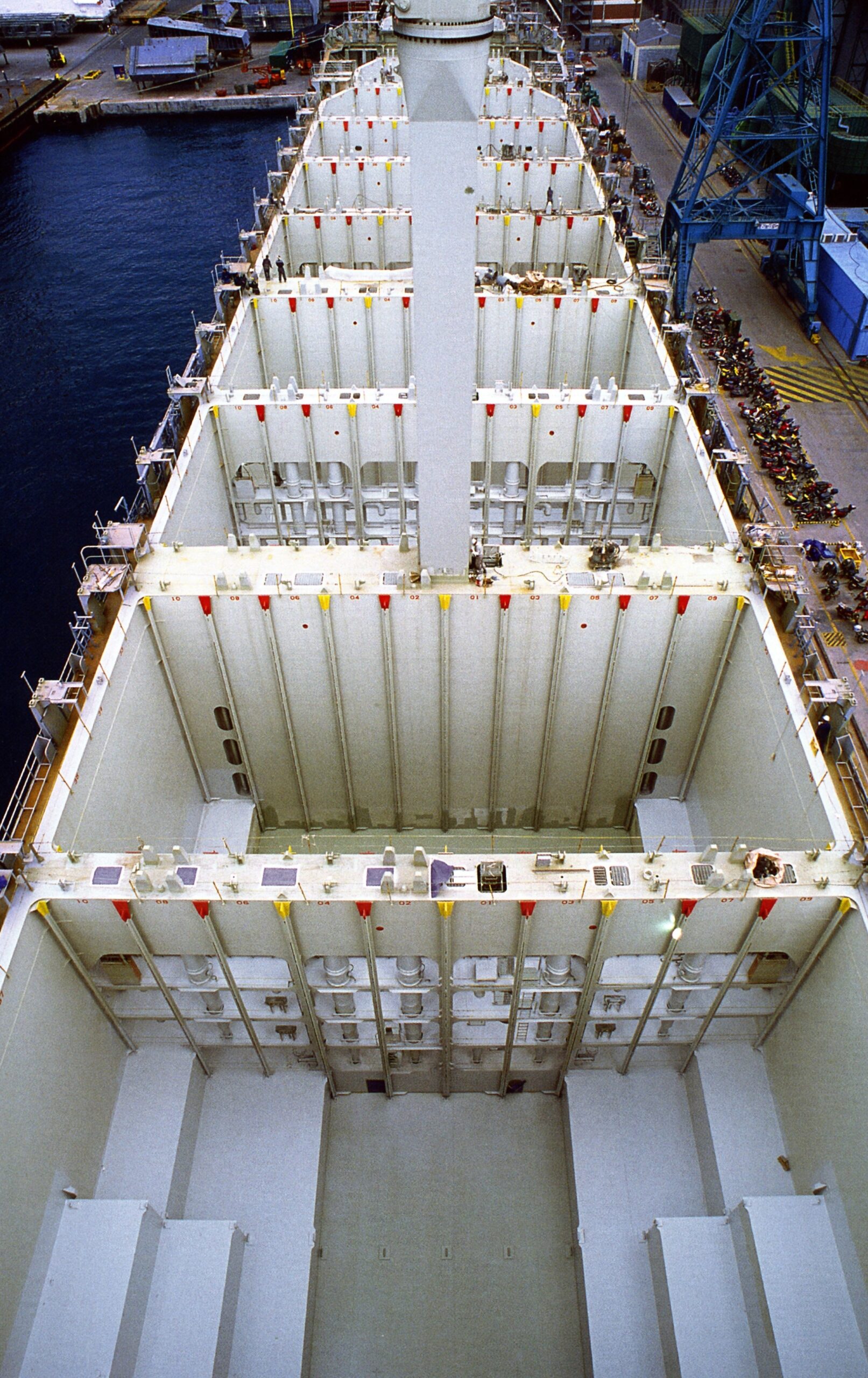

Containerized systems would not necessarily be restricted to a single standard size so long as they utilize standard interfaces. The ability to vary from specific limits and how commercial containerships are not as weight limited as conventional warships are important distinctions from the mission module approach of the Littoral Combat Ships (LCS). With the LCS program, the design was driven in a direction that did not allow for wide variance in module sizes without significant impacts to performance. By comparison, a commercial containership such as the U.S.-built Aloha-class can carry nearly 200, 40-foot containers in a single layer on deck, representing an area equivalent to more than four Independence-class LCS mission bays.1,2 Given deep container holds below deck, additional space between containers, and the ability to stack containers, the actual usable space is even greater.

Utilizing containerships to carry weapons, sensors, and other payloads provides for unique mission capabilities. Drop-in modules with integrated hatch covers could replace the standard container bay covers, and allow containerships to hold MK41 VLS tubes. Deck-mounted launchers for Naval Strike Missiles (NSM), Harpoon, and others could be mounted using standard interfaces. Similarly, SeaRAM, RAM, MK38 25mm guns, minelaying equipment, and other weapons stations could be deployed. And simply offering a large amount of seaborne flattop space could allow for conventional ground systems to be fired from the deck, such as missile artillery systems, Patriot batteries, NMESIS launchers, and the Army’s forthcoming SM-6 and Tomahawk launchers.3,4

Power and cooling would be provided by onboard interfaces, with the aforementioned Aloha class having ~8 MW of installed generation. Further augmentation could be provided on an as-needed basis by containerized generators and cooling units that would be cited near their users. Such units are readily available on the commercial market. Where systems require particular power quality or voltages, specific interface equipment would be incorporated.

In additional to weapon systems, any components that were built with compatible interfaces could be fielded. An obvious option would be sensors such as mobile radars or containerized versions of shipboard systems. With the large holds available and the typically sizeable tankage capacity of commercial containerships, underway replenishment gear could also be carried and the ships could augment the existing logistics force ships. There would also be potential to procure geared containerships, such as those with their own cranes, to allow for self-unloading, or facilitate the containership as an at-sea transfer point for other ships in permissive seas. These cranes could be designed-but-not-fitted in a practice already utilized in the commercial industry to allow conversion between ungeared and geared containerships. Those cranes, or other mission loadout cranes, could provide for VLS and other resupply not possible with the present Combat Logistics Force. For any ConRo ships purchased, these could augment the existing Roll-on/Roll-off (RoRo) ships in DOD inventory. This would potentially include making use of existing cargos and capabilities of those ships such as the Modular Causeway System (MCS) for establishing links to the beach in areas without developed port facilities.

Another usage would be as motherships for manned and unmanned aviation and small boats, with aircraft-rated containers allowing for the deployment of a large number of small UAVs or rotary aviation. Given the hundreds of tons of containers routinely loaded onto container hatch covers, this would not be a challenging design. The interior holds would provide further space for fuel while munitions, spares, and workshops could be provided on the deck. For larger unmanned assets, such as LUSV and MUSV, these ships could serve as at-sea service stations and as command nodes in certain areas.

Containerships could also make major contributions toward deception and challenging adversary decision-making. The usage of chaff, flares, decoy dispensers, and radar reflectors could be utilized to not only reduce the likelihood of a hit, but to also confuse opposing scouting efforts and complicate the battlespace with more signatures. Conventional warships typically field relatively few decoy dispensers, and a single containership deploying numerous decoys could make a major difference in shaping the electromagnetic footprint of a force on a theater-wide level. Furthermore, the suspected presence of these ships and their significant modularity could force adversaries to dedicate greater time to scouting and analysis in an attempt to understand the capability and operational roles of the containerships.

Survivability

Aside from the modules, the platforms would not be designed to military standards given how the added costs and complexity would negatively impact affordability. Containerships would not offer a highly survivable asset and would not be one-for-one replacements for conventional combatants. They would not be suitable for independent operations in high-threat environments and would not be able to keep up with carrier groups executing fast transits. They would not be suitable for surface action groups and formations that prioritized sustained speed, including actions deep within hostile Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2AD) zones. These should be acceptable tradeoffs for these ships given their cost and roles.

Instead, these ships would be used in concert with conventional combatants, often in rear areas, or in ways to minimize their likelihood of being engaged. More risky missions could be undertaken when required and may even be desirable in situations where other slower or vulnerable ships were included in the formation. This could include some U.S. and allied amphibious forces, auxiliaries, and even tankers and supply ships operating in support of particular operations. These ships could also provide support to forces operating in adjacent higher-threat areas, where those forces could provide targeting to containerships to leverage their magazine depth and long-range fires.

The ship would not be expected to fight through a hit, particularly against purpose-built anti-ship missiles or torpedoes. However, the containership’s sheer mass would provide a degree of resilience even without shock grade systems and conventional warship damage control capability. This would particularly be true if the hold space without mission equipment was filled with empty containers. The sheer size of the ship would on its own likely provide a degree of resilience, especially against smaller warheads such as the YJ-83 or similar weapons. These small warheads have proven to be relatively effective in achieving mission kills against small combatants, but multiple hits are likely required against larger ships. The flexible configuration of containerships will challenge the ability of advanced missiles to employ aimpoint selection capability to maximize lethal effect, which is much easier against conventional warships with the unchanging locations of their critical spaces, such as magazines and launch cells. Even if a mission kill is suffered, the prevention of total ship loss may allow for undamaged modular combat systems to be salvaged and retrieved. Equivalent systems may have otherwise been lost on conventional warships, whose combat systems are deeply integrated into their hulls.

Weapons targeted at naval formations featuring these containerships may be drawn toward the larger vessels, which enhances the survivability of the conventional warships that would suffer greater casualties and losses of capability from taking hits. Containership crew safety could be increased by utilizing armored command modules that serve as protected locations to command the ship. Containerships could feature multiple command modules to offer redundancy and resilience. Armored crew modules would not work for every mission set, such as flight operations where deck crews would be needed at times, but would allow for a degree of safety during an attack.

Procurement

The U.S. shipbuilding industrial base has shrunk greatly since its peak in World War II. The remaining yards have operated in a constrained environment for years but still produce ships for the Jones Act market, even if they do not have the ability to compete with the likes of South Korea, Japan, or China on total tonnage. While their costs are greater than foreign yards, a U.S.-built containership is still considerably more affordable than military ships.

The two-ship Aloha class was ordered from Philly Shipyard (formerly the Aker Philadelphia Shipyard) for $418 million in 2013 (around $512m in 2022 dollars), representing a unit cost of around $250 million. Matson paid a similar amount for their two Kanaloa-class ConRo ships from General Dynamics NASSCO, which entered service starting in 2020.5 If purchased in sufficient numbers, a containership or ConRo unit cost could be even less. Matson placed a 2022 order for three additional Aloha-class ships for $1 billion, an average unit price of about $333 million.6 By comparison, the FY10 LCS block buy featured a unit cost of about $440 million (or $590 in 2022 dollars).7 FFG 62 frigates are expected to cost about $1.1 billion per ship, LPD 17 Flight II ships are estimated at about $1.9 billion, and T-AO 205 oilers at about $680 million.8, 9, 10

Procurement of these containerships would not necessarily be intended as an alternative to current planned battle force procurements. Resource balancing will inevitably require budgetary trades as any Navy acquisition dollars spent on containerships would invariably impact potential spending on additional combatants. That said, there are industrial base limitations and only so many destroyers, frigates, and amphibious ships can be ordered per year on a sustained basis in the near-term.11

Containerships could be procured outside the traditional warship shipbuilding industrial base and offer opportunities. Adding containership production would be more affordable and adds production in currently underutilized domestic shipyards. Philly Shipyard’s only current government shipbuilding project is the replacement maritime academy training ships, National Security Multi-Mission Vessels (NSMV), via Tote Services.12 The first two vessels are being procured for about $315 million. Smaller shipbuilders that would struggle to produce a conventional warship would potentially be competitive for containerships contracts. Furthermore, mission packages could be competitively awarded separately from containership procurement.

If about $500 million per year was made available on a sustained basis, the Navy could likely order two containerships annually, not accounting for lead ship, mission module, and initial program stand-up costs. Since the program would utilize a relatively simple commercial design and leverage industry standards, the design would not require commonality when built at multiple yards. Of course, components such as main engines and generators would be advantageous to be common across all purchases. Study and analysis would be required to identify if the cost to acquire a common design can be offset by commonality savings.

Assuming a procurement rate of two ships per year, the Navy could have operational ships within five years from first delivery. The Navy could additionally purchase or lease used containerships to begin experimentation immediately while standing up the program. A steady ship order volume would also provide for improved stability of the commercial industrial base, lower unit costs, and potentially stimulate additional orders as costs decrease and expertise improves. Further positive impacts to the overall shipbuilding industrial base, to include military production, may also result from increased supplier stability and demand. Derivative hulls could also be explored as the basis for other auxiliary ships.

As the Navy grows its containership inventory and develops experience, many non-military containerships could be leveraged for operations and provide a vital source of surge capacity if needed. This could include wartime purchases of idle containerships and using already built mission systems.

As capabilities are upgraded, exchanged for new systems, or made obsolete, they would not require taking the ship itself out of service. A 30-year-old MK41 VLS or a 10-year-old radar might not be advisable to transfer and permanently install in a newer combatant with its full service life still ahead of it. The short-term nature of installing modular systems onto containerships would allow maximum service life to be extracted from the modular systems irrespective of the hulls they are installed on.

Personnel Configurations

The operating profile for these containerships could broadly follow several approaches: Navy-operated with uniformed sailors, Military Sealift Command (MSC) contract mariners, and through a ship-as-a-reservist approach. Balancing these approaches would require experimentation of how to best integrate them into the force.

The first approach would be the same as with current auxiliaries. The ships would be operated by the government and move government cargos. They may or may not carry weapons or sensors in this role, but could be loaded with such systems when desired for operations or exercises. When carrying weapon systems, Navy crews come aboard to operate. This approach would allow more permanent ship changes, including installing sensitive C4I systems, as the ships could remain under constant direct government control.

An alternative approach would be to employ a ship-as-a-reservist role where the containerships would be U.S.-flagged and operated commercially. The operating company could receive these ships at a discount in exchange for an agreement that they be provided in the event of national need and for a set number of regular training and experimentation periods. There may be value in Congressional action to approve a special approach under the Federal Ship Financing Program (Title XI) or through a new bill to reflect the outlined operational approaches.13 This would differ from typical subsidized purchases in that the ships would be expected to be used by the Navy on a semi-regular basis for exercises and other operations. In this approach, the shipping company would be responsible for most of the normal operating costs, while having benefited from a greatly reduced capital investment. The Navy would carry some or all of the cost of acquiring the ship and may award a fee to the operating company for use of the ship during the agreed upon periods each year to offset the lost revenue. Notionally, if the ship was activated for a few months every year or two, the Navy would be able to utilize these ships for various operations at a minimal cost compared with traditional auxiliaries.

Crewing these ships under the ship-as-a-reservist method could be handled several ways. One such method that may entice additional mariners and address a mariner shortfall would be to create a special reservist force. During normal times, these crew would operate the containerships in commercial service. When activated, some of the crew would also be activated as reservists. As part of this special service, they could be excluded from regular reservist status and only serve aboard the containerships. The option to allow them to focus on operating these ships without committing to the full scope of naval reservist status could be useful for recruitment and retainment. Specialists for sensor, weapon, and other modular systems would likely still be required, but this approach could provide crew fully qualified on shipboard systems without an extensive Navy training pipeline. The crewing approach would be evaluated and adapted to optimize it with additional operational experience and force structure integration as needed.

Conclusion

The Navy should add capacity, capability, and improved flexibility by pursuing containerships. They would provide direct mission support, combat logistics support, and more rapid testing of new systems and technologies. Given the nature of these ships, striking an appropriate balance of capability without concentrating too much valuable hardware on a single ship would be important to identify through analysis and wargaming. But these ships would certainly add hulls in an accelerated timescale while improving U.S. domestic shipbuilding capacity, compared to ramping up conventional warship production within the tight limits of the industrial base. Pursuing containerships would leverage underutilized capacity at a fraction of typical combatant costs and deliver a unique capability on a timescale unmatched by most other options.

Tyler Totten is a naval engineer supporting Navy ship programs including EPF, LCS, and DDG(X), with a deep interest in international and specifically maritime security. He is also an amatuer science fiction writer published on Kindle. He holds a B.S from Webb Institute in Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering. He can be found on Twitter at @AzureSentry.

References

1. Aloha Class 3,600 TEU CV-LNG Ready. (2015, November 25). Retrieved from Philly Shipyard: https://www.phillyshipyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/3600_TEU_data_sheet.pdf

2. Independence class Littoral Combat Ship – LCS. (2022). Retrieved from seaforces.org: https://www.seaforces.org/usnships/lcs/Independence-class.htm.

3. Martin, L. (2022, December 5). Retrieved from Lockheed Martin: https://news.lockheedmartin.com/2022-12-2-Lockheed-Martin-Delivers-Mid-Range-Capability-Weapon-System-to-the-United-States-Army.

4. Fabey, M., & Roque, A. (2022, April 20). Retrieved from Janes: https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/pentagon-budget-2023-usmc-sees-nmesis-as-marquee-system-for-new-approach.

5. Schuler, M. (2020, January 06). Matson Takes Delivery of First Kanaloa-Class ConRo. Retrieved from gCaptain: https://gcaptain.com/matson-takes-delivery-of-first-kanaloa-class-con-ro/.

6. Matson. (2022, November 02). Matson to Add Three LNG-Powered Aloha Class Containerships. Retrieved from PR Newswire: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/matson-to-add-three-lng-powered-aloha-class-containerships-301666764.html#:~:text=The%20854%2Dfoot%20Aloha%20Class,hallmark%20%E2%80%93%20timely%20delivery%20of%20goods.

7. USN. (2011, January 05). Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) contract award announced. Retrieved from The Flagship: https://www.militarynews.com/norfolk-navy-flagship/news/top_stories/littoral-combat-ship-lcs-contract-award-announced/article_a3609a94-d562-54cd-b6fc-a31601cbf785.html.

8. O’Rourke, R. (2022). Navy Constellation (FFG-62) Class Frigate Program. Washington DC: Congressional Research Service.

9. (O’Rourke, Navy LPD-17 Flight II and LHA Amphibious Ship Programs: Background and Issues for Congress, 2022.

10. (O’Rourke, Navy John Lewis (TAO-205) Class Oiler Shipbuilding Program: Background and Issues for Congress, 2022)

11. Shelbourne, M., & LaGrone, S. (2023, January 10). CNO Gilday to Shipbuilders: ‘Pick Up the Pace’. Retrieved from USNI News: https://news.usni.org/2023/01/10/cno-gilday-to-shipbuilders-pick-up-the-pace.

12. Philly Shipyard. (2022). Government Projects – National Security Multi-Mission Vessel (NSMV). Retrieved from https://www.phillyshipyard.com/government-projects/.

13. US DOT Maritime Administration. (2022, June 23). Federal Ship Financing Progrm Title XI). Retrieved from Maritime Administration: https://www.maritime.dot.gov/grants/title-xi/federal-ship-financing-program-title-xi.

Featured Image: An A13-class container ship. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)