By Austin Hale

The future of naval warfare is increasingly shifting to undersea competition, in both manned and unmanned systems. American seapower has excelled in this domain and holds a competitive edge today beneath the waves. But the U.S. Navy, by a combination of compressed funding and potentially crippling procurement cost increases, may not be well positioned to sustain its mastery of undersea warfare.

Today’s Eroding Competitive Advantage

Near-peer competitors, such as Russia and China, are both committed to improving their undersea capabilities. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) now possesses one of the largest fleets in the world, with more than 300 ships, including five SSNs, four SSBNs, and 53 diesel-powered attack submarines (SS/SSPs).1 Russia has engaged in increasingly hostile naval activity, including targeted provocations and intimidation of NATO partners and allies, and continues procurement of the fast, heavily armed, and deep diving Severodvinsk-class SSN/SSGN.2 Additionally, China’s and Russia’s development of Anti-access/Area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities pose a major threat to the United States’ ability to secure sea control in their respective regions and, in the case of China, threaten critical United States naval facilities in the Western Pacific.3

Furthermore, these challenges come at a time when dwindling numbers and the need to replace aging ships have placed the submarine force under a tremendous amount of pressure to meet its existing obligations to Combatant Commanders (CCDR). In a March 2016 hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee, Admiral John Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations, admitted that the Navy is only ‘‘able to meet about 50 to 60 percent of combatant commander demands right now’’ for attack submarines.4 Admiral Harry Harris Jr. affirmed this fact when he told lawmakers “we have a shortage in submarines. My submarine requirement is not met in PACOM, and I’m just one of many [combatant commanders] that will tell you that.”5

Submarine Force of the Future

In 2014, the Navy updated its 2012 Force Structure Assessment (FSA), concluding that a total battle force structure of 308 ships, including 48 SSNs, 0 SSGNs and 12 SSBNs, would be required to meet the anticipated needs of the Navy in the 2020s. While the projected 2017 submarine force—51 SSNs, 4 SSGNs and 14 SSBNs—currently exceeds the requirements as laid out in the March 2015 308-ship plan, the Navy anticipates a shortfall as Los Angeles-class SSNs are retired at a faster rate than Virginia-class SSNs are procured (See Table 1).6

| Table 1. Projected SSN Shortfall

(As Shown in the Navy’s FY2017 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan) |

|

Fiscal Year |

Annual Procurement Quantity |

Projected Number of SSNs |

SSN Shortfall relative to 48-ship goal |

| FY2017 |

2 |

52 |

|

| FY2018 |

2 |

53 |

|

| FY2019 |

2 |

52 |

|

| FY2020 |

2 |

52 |

|

| FY2021 |

1 |

51 |

|

| FY2022 |

2 |

48 |

|

| FY2023 |

2 |

49 |

|

| FY2024 |

1 |

48 |

|

| FY2025 |

2 |

47 |

1 |

| FY2026 |

1 |

45 |

3 |

| FY2027 |

1 |

44 |

4 |

| FY2028 |

1 |

42 |

6 |

| FY2029 |

1 |

41 |

7 |

| FY2030 |

1 |

42 |

6 |

| FY2031 |

1 |

43 |

5 |

| FY2032 |

1 |

43 |

5 |

| FY2033 |

1 |

44 |

4 |

| FY2034 |

1 |

45 |

3 |

| FY2035 |

1 |

46 |

2 |

| FY2036 |

2 |

47 |

1 |

| FY2037 |

2 |

48 |

|

| FY2038 |

2 |

47 |

1 |

| FY2039 |

2 |

47 |

1 |

| FY2040 |

1 |

47 |

1 |

| FY2041 |

2 |

47 |

1 |

| FY2042 |

1 |

49 |

|

| FY2043 |

2 |

49 |

|

| FY2044 |

1 |

50 |

|

| FY2045 |

2 |

50 |

|

| FY2046 |

1 |

51 |

|

Source: Table adapted from information presented in Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement, Ronald O’Rourke, CRS. May 27, 2016.

As depicted in Table 1, the Navy’s FY2017 30-year SSN procurement plan calls for the procurement of 44 Virginia-class SSNs by FY2046, with production varying from one to two SSNs per fiscal year, at a cost of $2.4 billion each.7 If implemented, the SSN force would drop below the 48-ship requirement beginning in FY2025, reach a minimum of 41 ships in FY2036 and would not meet the 48-ship requirement until FY2041.8

Beginning FY2027, the Navy’s 14 Ohio-class SSBNs are scheduled for retirement at a pace of one ship per year until the class is retired in FY2040. Table 2 shows the Navy’s schedule for the retirement of the Ohio-class SSBNs and the procurement of 12 Columbia-class SSBNs set to begin replacing the Ohio-class in FY2030.9

| Table 2. FY2017 Navy Schedule for Replacing Ohio-class SSBNs |

|

Fiscal Year |

Number of Columbia-class SSBNs procured each year |

Cumulative number of Columbia-class SSBNs in service |

Ohio-class SSBNs in service |

Combined Ohio– and Columbia-class SSBNs in service |

| FY2019 |

|

|

14 |

14 |

| FY2020 |

|

|

14 |

14 |

| FY2021 |

1 |

|

14 |

14 |

| FY2022 |

|

|

14 |

14 |

| FY2023 |

|

|

14 |

14 |

| FY2024 |

1 |

|

14 |

14 |

| FY2025 |

|

|

14 |

14 |

| FY2026 |

1 |

|

14 |

14 |

| FY2027 |

1 |

|

13 |

13 |

| FY2028 |

1 |

|

12 |

12 |

| FY2029 |

1 |

|

11 |

11 |

| FY2030 |

1 |

1 |

10 |

11 |

| FY2031 |

1 |

2 |

9 |

11 |

| FY2032 |

1 |

2 |

8 |

10 |

| FY2033 |

1 |

3 |

7 |

10 |

| FY2034 |

1 |

4 |

6 |

10 |

| FY2035 |

1 |

5 |

5 |

10 |

| FY2036 |

|

6 |

4 |

10 |

| FY2037 |

|

7 |

3 |

10 |

| FY2038 |

|

8 |

2 |

10 |

| FY2039 |

|

9 |

1 |

10 |

| FY2040 |

|

10 |

|

10 |

| FY2041 |

|

11 |

|

11 |

| FY2042 |

|

12 |

|

12 |

Source: Table adapted from Navy Columbia Class (Ohio Replacement) Ballistic Missile Submarine (SSBN[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, Ronald O’Rourke, CRS, October 3, 2016.

As can be seen in Table 2, the proposed Columbia-class program schedule calls for the procurement of the new SSBNs to begin in FY2021, with the last ship being procured in FY2035 with all 12 boats entering into service by FY2042. Under this proposed procurement plan, the Navy’s “boomer” force will drop below the stipulated 12-ship requirement by one or two ships between FY2029 – FY2041.10

Submarines in the 350-Ship Navy

The Navy has recently updated its assessment of the fleet and has proposed a larger 355-ship force.11 The resource implications of building and manning almost 70 more ships beyond today’s fleet is daunting. The underlying strategic rationale for this force and its resource implications have not well-articulated by the new Pentagon leadership or the administration. Of particular note, the force structure assessment calls for 66 SSNs.

The Navy’s new plan is supported by other analysts who have advocated for alternative force structures. According to the Heritage Foundation, the Navy should be composed of 346 ships, with 55 SSNs.12 Another alternative structure, developed by Bryan Clark at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, proposes a fleet architecture “to provide the United States an advantage in great power competition with China and Russia or against capable and strategically located regional powers such as Iran.”13 This proposed architecture calls for a fleet composed of 343 ships, with 66 SSNs. In another proposed alternative, analysts at the Center for a New American Security conclude that a 350-ship navy is “the bare minimum that is actually requires to maintain presence in the 18 maritime regions where the United States has critical national interest” and calls for the enlargement of the Navy’s SSN force to “more than 70” ships.14

It is clear from these studies that conventional wisdom from the naval cognoscenti shows a strong consensus for not only sustaining our submarine force but actually increasing it. It is equally clear that the U.S. Navy’s shipbuilding plan is unlikely to achieve the desired fleet totals and that the plan, in its current state—that is largely based on optimistic cost assessment factors—is unfeasible. The administration may resolve that with an infusion of funding but sustainable support may not be forthcoming from either OMB or the Congress. Moreover, there are plausible factors that could exacerbate the shipbuilding crisis for the Navy that could cripple even today’s nearly anemic plan. This paper explores that scenario.

Potential Problems

In pursuing its proposed SSN and SSBN procurement plan, the Navy faces a number of potential problems. One major concern is the anticipated cost of the Columbia-class program and its potential impact on other Navy shipbuilding and procurement programs. According to the Navy’s 2014 estimate, the cost of the lead ship is approximately $14.5 billion in constant TY dollars, with the average cost of ships 2-12 at $9.8 billion in constant TY dollars.15 Measured in constant FY17 dollars, the total cost for the program will be over $100B.16 Given the Navy’s FY2017 budget, Navy officials have been consistently concerned that procurement of the Columbia-class will adversely affect other Navy programs. As Admiral Jon Greenert, then Chief of Naval Operations, testified to a House subcommittee on February 26, 2015:

“In the long term beyond 2020, I am increasingly concerned about our ability to fund the Ohio Replacement ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) program—our highest priority program—within our current and projected resources. The Navy cannot procure the Ohio Replacement in the 2020s within historical shipbuilding funding levels without severely impacting other Navy programs.”17

However, given the current budget constraints under the Budget Control Act of 2011, as amended, and the Navy’s current share of the overall Department of Defense budget—nearly 28 percent in FY2017— it is unlikely that the Navy will receive the robust funding it needs from both its Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy (SCN) account and the National Sea-Based Deterrent Fund (NSBDF).18

As a critical program for the nation due to its status within the strategic deterrence force and the Navy’s designated top priority, the Columbia-class program will be fully funded and any resulting pressures on SCN account will be borne by other Navy programs.19 In testimony delivered to the House Armed Service Committee on February 25, 2015, Navy officials testified that:

“Absent a significant increase to the SCN [Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy] appropriation [i.e., the Navy’s shipbuilding account], OR SSBN construction will seriously impair construction of virtually all other ships in the battle force: attack submarines, destroyers, and amphibious warfare ships.”20

Any negative impact on the construction of other ships will commensurately impact the shipbuilding industrial base, reducing economies of scale, causing shipbuilding cost to “spiral unfavorably.”21 Thus, the Navy clearly recognizes that its current shipbuilding plan is highly risky and cannot be reasonably executed without additional funding.

Even with additional funding, it is entirely possible that the funds would be used to properly fund the shipbuilding account or meet unplanned cost growth. Historically, the Navy has systematically underestimated the cost of procuring new ships and the accuracy of the Navy’s estimated procurement cost for the Columbia-class ship is soft at best. In an October 2015 report by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), it was estimated that the Navy’s FY2016 30-year Shipbuilding Plan underestimated the cost of Virginia-class SSNs by around three percent and the cost of the Columbia-class ships by as much as 22 percent.22 Historical underestimation of shipbuilding cost led CBO to estimate that the lead Columbia-class SSBN would cost 13.2 billion in FY2015 dollars, with boats 2 through 12 costing $6.8 billion in FY2015 dollars, an average of $7.1 billion per ship.23 This cost growth would consume more of the Navy’s constrained shipbuilding and procurement accounts, and either stretch out the program (increasing total costs) or more likely, divert funds from Virginia-class production.

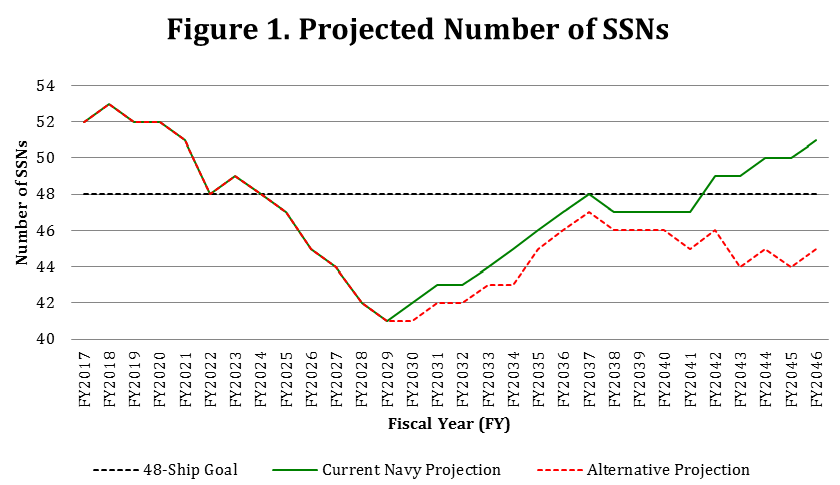

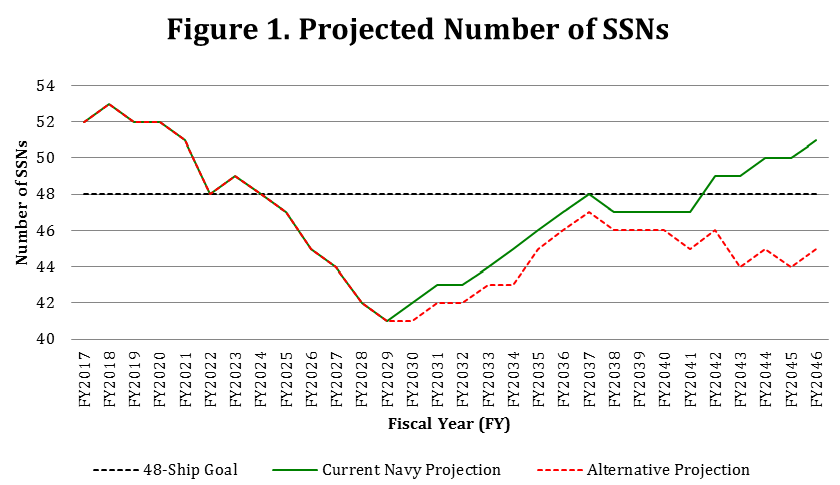

Given how the Navy has increased its requirement for ships and submarines while underestimating the cost of programs, it is very possible that the Navy will be able to afford to procure only one SSN per year after FY2023. The implications of this scenario are profound for undersea dominance (see Table 3). Without substantial increases in the Navy’s shipbuilding accounts or successful acquisition management of the predicted costs of the Columbia-class SSBN program, it is likely that the SSN shortfall will be more severe and lengthier than depicted.

| Table 3. Adjusted Projected SSN Shortfall

(Adjusted by reducing the total SSN procurement from 2 to 1 in FY2025 and FY2036-FY2039 and FY2041) |

|

Fiscal Year |

Annual Procurement Quantity |

Projected Number of SSNs |

SSN Shortfall relative to 48-ship goal |

| FY2017 |

2 |

52 |

|

| FY2018 |

2 |

53 |

|

| FY2019 |

2 |

52 |

|

| FY2020 |

2 |

52 |

|

| FY2021 |

1 |

51 |

|

| FY2022 |

2 |

48 |

|

| FY2023 |

2 |

49 |

|

| FY2024 |

1 |

48 |

|

| FY2025 |

1 |

47 |

1 |

| FY2026 |

1 |

45 |

3 |

| FY2027 |

1 |

44 |

4 |

| FY2028 |

1 |

42 |

6 |

| FY2029 |

1 |

41 |

7 |

| FY2030 |

1 |

41 |

7 |

| FY2031 |

1 |

42 |

6 |

| FY2032 |

1 |

42 |

6 |

| FY2033 |

1 |

43 |

5 |

| FY2034 |

1 |

43 |

4 |

| FY2035 |

1 |

45 |

3 |

| FY2036 |

1 |

46 |

2 |

| FY2037 |

1 |

47 |

1 |

| FY2038 |

1 |

46 |

2 |

| FY2039 |

1 |

46 |

2 |

| FY2040 |

1 |

46 |

2 |

| FY2041 |

1 |

45 |

3 |

| FY2042 |

1 |

46 |

2 |

| FY2043 |

2 |

44 |

4 |

| FY2044 |

1 |

45 |

3 |

| FY2045 |

2 |

44 |

4 |

| FY2046 |

1 |

45 |

3 |

Source: Table adapted from information presented in Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement, Ronald O’Rourke, CRS, May 27, 2016.

As can be seen in Table 3, if procurement of Virginia-class SSNs is reduced from two to one per FY in FY2025, FY2036-FY2039 and FY2041, the shortfall of SSNs will continue beyond FY2046. Furthermore, by FY2046 the Navy will have six less SSNs than predicted in its 30-year Shipbuilding Plan and be three SSNs short of its 48-ship goal (See Figure 1).

Implications and Mitigation Discussion

The first implication of this scenario is the need for senior Navy leaders to gain approval and the requisite funding for their Force Structure Assessment from the new Administration and Congress. The second implication is the need to prioritize available SCN funding for Virginia-class attack boats to ensure that the potential “crash dive” scenario does not come about.

That said, we still foresee a drop in capacity in the near to mid-term that will increase operational risks. To mitigate the impact of the major shortage of SSNs would have on the Navy’s undersea forces, it is recommended that the Navy continue to explore and expand its use of unmanned undersea vehicles (UUVs). As advancements in technology continue to improve the undersea surveillance and monitoring capacity of long-loiter unmanned systems, unmanned undersea operations will be the next frontier in naval warfare.24 As Bryan Clark notes:

“With computer processing power continuing to rapidly increase and become more portable, dramatic breakthroughs are imminent in undersea sensing, communications, and networking. Advancements are also underway in power generation and storage that could yield significant increases in the endurance, speed, and capability of unmanned vehicles and systems. These improvements would compel a comprehensive reevaluation of long-held assumptions about the operational and tactical employment of undersea capabilities, as well as the future design of undersea systems.”25

As the seabed grows in economic and military importance, UUVs can act “as force multipliers and risk reduction agents for the Navy” and work autonomously or in conjunction with manned systems conducting a wide range of missions.26

UUVs can be used to monitor United States and allied seabed systems and survey, and if necessary attack, adversary’s seabed systems. Furthermore, UUVs can provide access to areas that are too hazardous or too time consuming to reach with manned platforms. With this enhanced access, UUVs could act as long-term ISR platforms and provide real-time, over-the-horizon targeting information for manned vessels.27 Likewise, large-scale UUVs could also be used to conduct intelligence gathering missions because of their ability to carry a lot of advanced sensors at a fraction of the cost of the Virginia-class SSN. The Navy is pursuing extra-large unmanned undersea vehicles with this in mind.28 Allowing UUVs to conduct such missions not only unburdens the SSN fleet, but also minimizes the risks to the multi-billion dollar Virginia-class SSNs and their crews.

Furthermore, UUVs have the capacity to conduct routine yet important and repetitive missions that may not require the attention of multi-million dollar manned vessels. For example, UUVs could be used to maintain and observe valuable undersea infrastructure—such as the U.S. undersea cables that carry the bulk of the world’s Internet data.

Another important capability of UUVs is their potential to provide the Navy with an option for non-lethal sea control. As pointed out in the most recent Navy Unmanned Undersea Vehicle (UUV) Master Plan, “current undersea capabilities limit options for undersea engagement of undersea and surface targets to either observation/reporting or complete destruction.”29 Non-lethal options provided by UUVs could be used in situations short of war and support de-escalation during times of heightened tension.30

Adding to the potential efficacy of UUVs is their ability to be deployed and recovered stealthily from submarines. Beginning with Block V Virginia-class SSNs—procurement set to begin in 2019—the Navy plans to build its SSNs with an additional mid-body section, known as the Virginia Payload Module (VPM). Nearly 70 feet in length and containing 4 large-diameter, vertical launch tubes, the VPM increases the amount of Tomahawk cruise missiles or other payloads that the Virginia-class can carry from 37 to about 65—more than tripling the offensive capability of each ship.31 In addition to increasing the storage capacity for missiles, the VPM also has the ability to store and launch Large UUVs up to 80-inches in diameter.32 Not only does this capability allow UUVs to deploy significantly closer to enemy territory and military infrastructure, but also greatly increases the range at which submarines can track adversary’s vessels. As Rear Adm. Barry Bruner, then chief of the Undersea Warfare Division (N97) stated in reference to UUVs, “it sure beats the heck out of looking out of a periscope at a range of maybe 10,000 to 15,000 yards on a good day… Now you’re talking 20 to 40 miles.”33

Conclusion

As Russia and China continue to improve their undersea capabilities, the competitive advantage long enjoyed by the United States in undersea warfare will continue to diminish. This challenge to U.S. naval hegemony comes at a time when the Navy’s fleet of SSNs is struggling to meet existing obligations to Combatant Commanders around the globe, and is set to suffer a shortfall in the number of available attack submarines in the near future. Exacerbating the expected shortfall is the strategic necessity of building the Columbia-class SSBN; a program that is likely to exceed its predicted cost. The new administration may provide very significant increases to the Pentagon’s coffers that could offset much of the concerns raised in this article, but probably not all of them. To mitigate the impact of the SSN shortage it is imperative that the Navy focus on submarine production and move more aggressively into the development and procurement of advanced UUVs. As so eloquently put forth by Dr. T. X. Hammes, it is time for the United States to embrace the small, many and smart over the few and exquisite.34

Austin Hale is currently working as a research intern at the National Defense University’s Center for Strategic Research and is a student at George Washington University. Special thanks to Dr. F. G. Hoffman for guidance and editorial assistance on this project.

References

1. Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2016,” Washington, DC (April 2016): 25-26, http://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2016%20China%20Military%20Power%20Report.pdf

2. Kathleen Hicks, Andrew Metrick, Lisa Sawyer Samp and Kathleen Weinberger, “Undersea Warfare in Northern Europe,” Washington, DC: Center for Security and International Studies (July 2016): 7, https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/160721_Hicks_UnderseaWarfare_Web.pdf; Dave Majumdar, “Russia’s Next Super Submarine Is Almost Ready for War,” The National Interest, March 27, 2016, http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/russias-next-super-submarine-almost-ready-war-15610?page=show.

3. Dmitri Trenin, “The Revival of the Russian Military,” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2016, 23–29, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2016-04-18/revival-russian-military; Office of Naval Intelligence, “The Russian Navy: A Historic Transition,” Washington DC (December 2015), http://www.oni.navy.mil/Portals/12/Intel%20agencies/russia/Russia%202015print.pdf?ver=2015-12-14-082038-923; Stephen Frühling and Guillaume Lasconjarias, “NATO, A2AD, and the Kaliningrad Challenge,” Survival, Vol. 58, no. 2 (March 2016), 95–116; Sydney J. Freedberg Jr “Russians In Syria Building A2/AD ‘Bubble’ Over Region: Breedlove,” BreakingDefense,” September 28, 2015, accessed at http://breakingdefense.com/2015/09/russians-in-syria-building-a2ad-bubble-over-region-breedlove/; Guillaume Lasconjarias and Alessandro Marrone, “How to Respond to Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD)? Towards a NATO Counter-A2AD Strategy,” Rome: NATO Defense College, Conference Report No. 01/16, February 2015; Mikkel Vedbey Rasmussen, “A2/AD Strategy for Deterring Russia in the Baltics,” in Baltic Sea Security, ed. Ann-Sofie Dahl (Centre for Military Studies, University of Copenhagen, 2015), 37-39, http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/publikationer/2015/Baltic_Sea_Security__final_report_in_English.pdf; Major Christopher J. McCarthy, “Anti-Access/Area Denial: The Evolution of Modern Warfare,” Lucent: A journal of National Security Studies, 2010, 3, https://www.usnwc.edu/Lucent/OpenPdf.aspx?id=95.

4. Dave Majumdar, : The U.S. Navy’s Master Plan to Rebuild Its Sub Fleet,” The National Interest, March 16, 2016, http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/the-us-navys-master-plan-rebuild-its-sub-fleet-15515.

5. Franz Stefan-Gady, “US Admiral: ‘China Seeks Hegemony in East Asia,’” The Diplomat, February 25, 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2016/02/us-admiral-china-seeks-hegemony-in-east-asia/.

6. Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress,” 9; Congressional Budget Office, “The U.S. Military’s Force Structure: A Primer,” 59 and 117.

7. Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress,”10.

8. Ibid., 10.

9. O’Rourke, “Navy Columbia Class, Background and Issues for Congress,” 7.

10. Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Columbia Class (Ohio Replacement) Ballistic Missile Submarine (SSBN[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress,” 7.

11. The executive summary can be found at https://news.usni.org/2016/12/16/document-summary-navys-new-force-structure-assessment. For some criticism see Bryan McGrath, “Quick Review of the Navy’s New Force Structure Assessment,” War on the Rocks, December 16, 2016.

12. “U.S. Navy,” 2017 Index of U.S. Military Strength, The Heritage Foundation, available at http://index.heritage.org/military/2017/assessments/us-military-power/u-s-navy/.

13. Bryan Clark, email on Alternative Future Fleet Architecture Study, 16 Jan. 2017.

14. Jerry Hendrix, “12 Carriers and 350 Ships: A Strategic Path Forward from President Elect Donald Trump,” The National Interest, November 14, 2016, http://nationalinterest.org/feature/12-carriers-350-ships-strategic-path-forward-president-elect-18395.

15. Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Columbia Class (Ohio Replacement) Ballistic Missile Submarine (SSBN[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress,” 10-12.

16. Sydney J. Freedberg, Jr., “Columbia Costs, Is it $100B or $128B?,” BreakingDefense, Jan. 9, 2017, http://breakingdefense.com/2017/01/columbia-costs-is-it-100b-or-128b-well-yes-read-the-adb-memo/

17. Statement of Admiral Jonathan Greenert, U.S. Navy Chief of Naval Operations, Before the House Subcommittee on Defense, Committee on Appropriations on FY2016 Department of Navy Posture (26 February 2015): 7, accessed at http://www.navy.mil/cno/docs/150303%20_CNO_Posture.pdf.

18. Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Force Structure: A Bigger Fleet? Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service (November 2016): 7, available at https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/weapons/R44635.pdf; Sam LaGrone, “FY 2017 Budget: Tight Navy Budget in Line With Pentagon Drive for High End Warfighting Power But Brings Increased Risk,” USNI News, February 29, 2016, https://news.usni.org/2016/02/09/fy-2017-budget-tighter-navy-budget-in-line-with-pentagon-drive-for-more-high-end-warfighting-power.

19. Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Columbia Class (Ohio Replacement) Ballistic Missile Submarine (SSBN[X]) Program: Background and Issues for Congress,” 25.

20. Ibid., 25.

21. Ibid., 25.

22. Congressional Budget Office, “An Analysis of the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2016 Shipbuilding Plan,” Washington, DC (October 2015): Appendix B, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/reports/50926-Shipbuilding-2.pdf

23. Ibid., 25.

24. For a forecast in this area, see Bryan Clark, “The Emerging Era in Undersea Warfare,” Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (September 2016), 8–16 available at http://csbaonline.org/research/publications/undersea-warfare/publication; Christian Davenport, “The New Frontier for Drone Warfare: Under the Oceans,” The Washington Post, November 25, 2016, A16.

25. Bryan Clark, et al. “Alternative Future Fleet Architecture Study,” 16.

26. Department of the Navy, “The Navy Unmanned Undersea Vehicle (UUV) Master Plan,” (November 9, 2004): xvii, http://www.navy.mil/navydata/technology/uuvmp.pdf; Department of the Navy, Report to Congress: Autonomous Undersea Vehicle Requirements for 2025 (February 2016): 3, available at https://news.usni.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/18Feb16-Report-to-Congress-Autonomous-Undersea-Vehicle-Requirement-for-2025.pdf#viewer.action=download.

27. Report to Congress: Autonomous Undersea Vehicle Requirements for 2025 (February 2016): 8.

28. Valerie Insinna, “Navy About to Kick Off Extra Large UUV Competition,” Defense News, January 10, 2017.

29. Report to Congress: Autonomous Undersea Vehicle Requirements for 2025 (February 2016): 5.

30. Ibid., 5.

31. O’Rourke, “Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class: Background and Issues for Congress,” 7.

32. Dave Majumdar, “Russia vs. America: The Race for Underwater Spy Drones,” The National Interest, January, 21 2016, http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/america-vs-russia-the-race-underwater-spy-drones-14981.

33. Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “Run Silent, Go Deep: Drone-Launching Subs To Be Navy’s ‘Wide Receivers,” Breaking Defense, October 26, 2012, http://breakingdefense.com/2012/10/run-silent-go-deep-drone-launching-subs-to-be-navys-wide-rec/.

34. T.X. Hammes, “The Future of Ware: Small, Many, Smart vs. Few & Exquisite?,” War on the Rocks, July 16, 2014, http://warontherocks.com/2014/07/the-future-of-warfare-small-many-smart-vs-few-exquisite/

Featured Image: Electric Boat workers prepare submarine Illinois for rollout on July 24, 2015. (Photo: General Dynamics Electric Boat)