This is an article in our first “Non Navies” Series.

Background

Fisheries crime is a major and increasingly significant threat not only to the security of the maritime environment but also to the sustainability of marine living resources. In a study conducted by the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) on transnational criminal activities in the fishing industry, it was highlighted that:

- Fishers trafficked for the purpose of forced labour on board fishing vessels are severely abused;

- There is frequency of child trafficking in the fishing industry;

- Transnational organised criminal groups are engaged in marine living resource crimes in relation to high value, low volume species such as abalone;

- Some transnational fishing operators launder illegally caught fish through transhipments at sea and fraudulent catch documentation;

- Fishing licensing and control system is vulnerable to corruption;

- Fishing vessels are used for the purpose of smuggling of migrants, illicit traffic in drugs (primarily cocaine), illicit traffic in weapons, and acts of terrorism; and

- Fishers are often recruited by organised criminal groups due to their skills and knowledge of the sea and are seldom masterminds behind organised criminal activities involving the fishing industry or fishing vessels.[1]

Some of the specific incidents of transnational crime in fisheries include the hijacking of the MV Kuber for the purpose of transporting terrorists and arms into Mumbai; hijacking of fishing vessels and involvement of fishers in piracy attacks in the western Indian ocean;[2] smuggling of weapons into off the coast of the Red Sea; human trafficking for the purpose of forced labour in Thailand fishing industry; and the illegal capture and trade of high value species by criminal syndicates in Australia and South Africa.[3]

Factors that make the fishing industry susceptible to transnational organised crime include the global reach of fishing vessels, ineffective monitoring of fishing vessels, lack of transparency on the identity of beneficial owners of vessels, continuous decline of global stocks, poor socio-economic conditions of fishers and fishing communities, lack of effective flag and port State jurisdiction, corruption, and inadequate international regulation on the safety of fishing vessels and working conditions of fishers.[4] Although fisheries crime is a burgeoning problem globally, its extent is difficult to determine with accuracy due to the elusive nature of illicit activities.

What is Fisheries Crime?

There is currently no legal definition of fisheries crime, fisheries-related transnational crime, or transnational crime in fisheries. To begin with, the scope and nature of IUU fishing as set out in the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter, and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing (IPOA-IUU) does not cover fisheries crime. The definition of illegal fishing in various domestic legislation also shares the same limitation.

The relationship between illegal fishing (and broadly illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing or IUU fishing) and transnational crime was first raised at the 9th meeting of the United Nations Open-ended Informal Consultative Process on Oceans and the Law of the Sea (UNICPOLOS) and at the meeting of the Conference of Parties to the UN Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime in 2008.[5] There were divergent views at these meetings on the potential link between illegal fishing and organised crime and it was decided that further studies are required before such connection may be established.[6] In 2010 the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 64/72 on sustainable fisheries where it noted concerns “about possible connections between international organized crime and illegal fishing in certain regions of the world…bearing in mind the distinct legal regimes and remedies under international law applicable to illegal fishing and international organized crime.[7] Succeeding UN General Assembly resolutions on Oceans and the Law of the Sea, as well as those on Sustainable Fisheries recognised the same conceptual correlation between illegal fishing and international organised crime but have yet to provide guidance on what their legal characterisation is.

The careful treatment of these two separate but related issues in international discussions is somehow justifiable. Apart from the lack of adequate studies on the subject, addressing transnational crime in fisheries is also muddled by jurisdictional issues. Illegal fishing is primarily a fisheries management issue addressed under the auspices of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) while transnational crime is dealt within the mandate of the UNODC. At the domestic level, addressing transnational crime in fisheries may involve a number of institutions such as our fisheries, customs, immigration, defence (navy), coastguard, and the police authorities. One can ask the question as to whose responsibility it is to respond to an incident involving cocaine trafficked by a fishing vessel? Is fishing vessel control still the issue here, or is this mainly a security threat? Is there sufficient relationship between resource sustainability and maritime security?

Now let us try to understand the complexity in finding the legal link between illegal fishing and transnational crime.

Is fisheries crime a transnational crime? Although the scope of the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime (UNTOC) does not include fisheries-related crime, the international agreement defines the transnational element of organised crime which may also be applied to fisheries. Art 3(2) of the Vienna Convention provides that a crime is transnational in nature if: it is committed in more than one State; it is committed in one State but a substantial part of its preparation, planning, direction or control takes place in another State; it is committed in one State but involves an organized criminal group that engages in criminal activities in more than one State; or it is committed in one State but has substantial effects in another State.[8] Examples of transnational crime include drug trafficking, trafficking in persons, including women and children, terrorism, internet-based criminal activities, money laundering, and corruption. Similar to these examples, the transnational element of fisheries crime may in the same vein make it a ‘serious crime’ within the same definition in Article 3(1). The definition of ‘organised criminal group’ under the Vienna Convention may also be used as a guide to generally characterise the operations of those involved in fisheries crime.

Is fisheries crime an organised crime? Organised crime is defined as “a continuing criminal enterprise that rationally works to profit from illicit activities that are often in great public demand. Its continuing existence is maintained through the use of force, threats, monopoly control, and/or corruption of public officials.”[9] This definition covers some of the examples we mentioned earlier such as trafficking in people in the fishing industry. It may also be emphasised that within the context of organised crime, activities are not limited to those involving criminal syndicates,[10] and therefore may encompass elements of corruption particularly in fishing vessel licensing.

Is fisheries crime a crime against nature or environmental crime? Although numerous studies have been conducted on the role of criminal law in addressing resource and environmental related offences,[11] the classification of illegal fishing, and broadly IUU fishing, as an environmental crime has not been uniformly and clearly established in international law unlike illegal logging, illegal traffic in wildlife, and illicit traffic in hazardous waste.[12] Existing literature defines transnational environmental crime, or sometimes referred to as eco-crime, as certain behaviour regarded as harmful or potentially harmful to the environment. In fisheries this largely includes illegal capture and trade of high value species involving organised criminal groups[13] and depending on the criteria set on what constitutes environmental crime, such characterisation may not necessarily include some of the examples of fisheries crime we highlighted above.

The argument that fisheries crime is both a transnational organised crime and environmental crime highlight the need for a thorough understanding of the nexus between fisheries and environmental law and transnational criminal law. Strengthening domestic legislation is therefore a key step in addressing this problem. This may include a clear identification of what activities may constitute fisheries crime, integrating provisions against criminal acts within fisheries legislation, and/or amending crimes-related legislation to link illegal fishing to transnational crime, and hence making it a predicate offence to money laundering.

Recognising issues in defining the scope of fisheries crime, a number of states in Australia have amended their legislation to include provisions on “trafficking in fish”. For example the New South Wales Fisheries Management Act (1994) provides for indictable species and quantity of fish which is currently limited to 50 abalones (Haliotis rubra) and 20 eastern rock lobsters (Jasus verreauxi). Trafficking in fish under this provision is punishable by a minimum of 10 years imprisonment. This legislation also provides that a court may also impose an additional penalty for the offence of up to ten times the market value of the fish as determined by a number of factors including the price and weight of the fish.[14] Changes to legislation have resulted in increased monitoring of the sale and transport of abalone and eastern rock lobster and successful prosecution of offenders.

Global Cooperation in Monitoring, Control, Surveillance and Enforcement to Combat Fisheries Crime

While the main issue for academics is finding the legal definition and scope of fisheries crime, our navies, coastguards, police, and other enforcement officers understand that the absence of such should not deter States from preventing and eliminating problem. Global and regional cooperation to combat fisheries crime is crucial to effectively deal with the transnational aspect of these illicit activities. Apart from discussions at the UN, a concrete and practical example of a global initiative to detect, suppress and combat fisheries crime is INTERPOL’s Project Scale which was launched in 2013. The objectives of Project Scale include raising awareness regarding fisheries crime and its consequences; establishing National Environment Security Task Forces to ensure cooperation between national and international agencies; assessing the needs of vulnerable member countries to effectively combat fisheries crimes; a and conducting operations to suppress crime, disrupt trafficking routes, and ensure the enforcement of national legislation. A Fisheries Crime Working Group was established under this initiative to develop the capacity, capability and cooperation of member countries to effective address fisheries crime. The Fisheries Crime Working Group also aims to facilitate the exchange of information, intelligence, and technical expertise between countries for the purpose of fisheries law enforcement. To date a number of countries have cooperated within the INTERPOL network and have called upon the international organisation to issue Purple Notices to illegal fishing vessels. INTERPOL’s Purple Notices are used to seek or provide information on the modus operandi, objects, devices and methods used by criminals.

The Code of Conduct Concerning the Repression of Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships and Illicit Maritime Activity in West and Central Africa adopted by 25 West and Central African countries in 2013 is a novel example of regional cooperation that recognises IUU fishing as a “transnational organised crime in the maritime domain” together with other well-established transnational criminal activities. Although the Code of Conduct does not provide specific characterisation of IUU fishing activities that may constitute transnational criminal acts, it provides a strong framework for cooperation to share and report incidents, interdict vessels engaged in IUU activities, apprehend and prosecute persons engaged in such illicit activities; and facilitate proper care, treatment and repatriation of fishermen and other personnel subject to transnational crime. The Code of Conduct also incorporates elements of the Djibouti Code of Conduct in the western Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Aden, as well as the Memorandum of Understanding on the integrated coastguard function network in west and central Africa developed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the Maritime Organization of West and Central Africa (MOWCA).

Strengthening Regional Cooperation

While multilateral cooperation to combat fisheries crime is still in its infancy, there are existing regional mechanisms that may be used to help to address the problem. Even though regional fisheries bodies do not have jurisdiction against fisheries crime, some of its measures may be used to promote awareness and identify specific fishing activities and vessels that may be used to perpetrate transnational crime. Flag State and port State measures may be used to investigate and take action against potential involvement of organised criminal groups in fishing activities while trade-related measures may be utilised to monitor the transit and prohibit the importation and exportation of fisheries products involved in such illicit activities. With more than 40 regional fisheries bodies established in the world’s oceans, sharing vessel and incident information with and through INTERPOL may be the most effective way to combat fisheries crime. Channels of cooperation may also be established between regional fisheries bodies and financial task forces established to combat money laundering and terrorism financing. There are currently anti-money laundering task forces established in the Asia Pacific, Caribbean, Europe, South America, Middle East, North Africa, West Africa, and Southern Africa that can enter into information exchange arrangements with relevant regional fisheries bodies and may also serve as conduits of information to the INTERPOL Fisheries Working Group and relevant work of the UNODC.

As the legal definition of fisheries crime is explored and the appropriate legal framework developed, there are more practical measures which can be adopted by States to combat the problem. These measures draw upon existing mechanisms and network of cooperation between States in order facilitate intelligence gathering and sharing of information and encourage inter-agency and cross institutional collaboration between relevant organisations in order to address an emerging maritime security issue.

[1] See UN Office of Drugs and Crime, Transnational Organized Crime in the Fishing Industry: Focus on Trafficking in Persons, Smuggling of Migrants, Illicit Drug Trafficking (UNODC: 2010), pp 1-3.

[2] United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, The Globalization of Crime: A Transnational Organized Crime Threat Assessment (UNODC: 2010) p 196.

[3] Gavin Hayman and Duncan Brack, International Environmental Crime: The Nature and Control of Environmental Black Markets, (London: Royal Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2002), at 7; See for example, Katherine M Anderson and Rob McCusker, ‘Crime in the Australian Fishing Industry: Key Issues,’ Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No 227 (Canberra: Institute of Criminology, 2005).

[4] Ibid., p. 3.

[5] United Nations, Conference of Parties to the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime, Report of the Conference of Parties to the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime on its Fourth Session, Vienna, 8-17 October 2008, CTOC/COP/2008/19, 1 December 2008, para. 210.

[6] United Nations General Assembly, Sixty-third session, Item 73(a) of the provisional agenda, Oceans and the law of the sea, Report on the works of the United Nations and the Law of the Sea at its Ninth Meeting, A/63/174, 25 July 2008, paras. 71 and 73.

[7] United Nations, Sustainable Fisheries, including through the 1995 Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks and Related Instrument, UNGA Resolution 63/112, 05 December 2008, para. 59.

[8]Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, opened for signature 15 November 2000, 40 ILM 335 (2001); UN Doc. A/55/383 at 25 (2000); UN Doc. A/RES/55/25 at 4 (2001), (entered into force 29 September 003), art 3(2).

[9] Jay S Albanese, Organized Crime in our Times (Newark: LexisNexis, 2007), p. 4

[10]Ibid, p. 5.

[11] A number of institutions have conducted studies on the protection of the environment by means of criminal law such as the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), the United Nations Asia and Far East Institute of Crime Prevention and Treatment of Offenders (UNAFEI), Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Criminal Law, Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC), and International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy. See United Nations, Economic and Social Council, Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, Report on the first session, 21-30 April 1992, Economic and Social Council Official Records 1992 Supplement No 10, E/1992/30, E/CN.15/1992/7, para. IV(1)(a).

[12] Environmental Investigation Agency, Environmental Crime: A Threat to Our Future (London: Emmerson Press, 2008).

[13]Donald R Liddick, Crimes Against Nature: Illegal Industries and the Global Environment (Sante Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2011), pp. 72-93.

[14] Australia, Fisheries Management Act 1994 (NSW), sec. 21C.

Dr Mary Ann Palma-Robles is a Visiting Senior Fellow at the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS), University of Wollongong, Australia. Apart from fisheries crime, her most recent research also focuses on trade measures to combat IUU fishing, fishing vessel and naval vessel encounters in disputed territories, and labour conditions in fisheries.

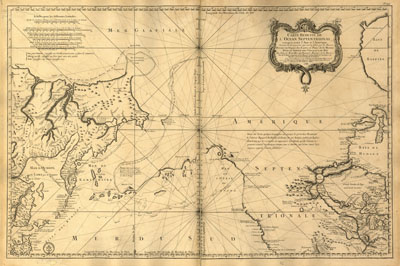

If you were aware of the grounding of the British fleet, and the deaths of over 2000 sailors, off the Isles of Scilly, west of Cornwall, in October 1707, then you are either the rare supercentenarian or you are a maritime history geek such as myself. All of this begs the question, why is this date in maritime history so important?

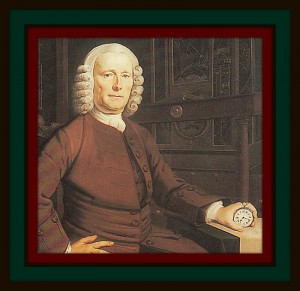

If you were aware of the grounding of the British fleet, and the deaths of over 2000 sailors, off the Isles of Scilly, west of Cornwall, in October 1707, then you are either the rare supercentenarian or you are a maritime history geek such as myself. All of this begs the question, why is this date in maritime history so important? second voyage (1772-1774). The Captain was so impressed with the chronometer that he was able to accurately chart the South Sea Islands. He eventually took the chronometer on his third and final voyage.

second voyage (1772-1774). The Captain was so impressed with the chronometer that he was able to accurately chart the South Sea Islands. He eventually took the chronometer on his third and final voyage.