CIMSEC is committed to keeping our content FREE FOREVER. Please consider donating to our annual campaign now so we can continue to provide free content.

By LTJG Kyle Cregge, USN

In response to the four recent mishaps, the U.S. Navy Surface Force is going through a cultural shift in training, safety, and mission execution. The new direction is healthy, necessary, and welcomed in the wake of the tragedies. Admiral Davidson’s “Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents” examines a myriad of different aspects of readiness in the Surface Force and the recommendations are far-reaching. There will likely be more training and scrutiny added to officer pipelines and ship certifications, some of which will come from the newly-created Naval Surface Group Western Pacific.

Included in the review were the subjects of Human Systems Integration (HSI) and Human Factors Engineering (HFE), in which the Review Team Members describe how “Navy ships are equipped with a navigation ‘system-of-systems,’” and that “The large number of different bridge system configurations, with increasingly complex and ship-specific guidance on how to make them work together, increases the burden on ships in achieving technical and operational proficiency.” I had the same experience – one where an Officer of the Deck (OOD) was challenged to monitor up to five different consoles with assistance from six different watchstanders while maintaining safety of navigation and executing the plan of the day. Thankfully, the recommendations in the Comprehensive Review address these difficulties, and five specifically address the immediate, unique needs of OODs:

- 3.2 Accelerate plans to replace aging military surface search RADARs and electronic navigation systems.

- 3.3 Improve stand-alone commercial RADAR and situational awareness piloting equipment through rapid fleet acquisition for safe navigation.

- 3.4 Perform a baseline review of all inspection, certification, assessment and assist visit requirements to ensure and reinforce unit readiness, unit self-sufficiency, and a culture of improvement.

- 3.8 As an immediate aid to navigation, update AIS laptops or equip ships with hand-held electronic tools such as portable pilot units with independent ECDIS and AIS.

- 3.13 Develop standards for including human performance factors in reliability predictions for equipment modernization that increases automation.

One solution to the recommendations would be the addition of Automated Celestial Navigation (CELNAV) systems which could provide additional navigation support to Bridge watchstanders. Specifically, the systems could continuously fix the ship’s position in both day and night with as good, if not better, accuracy provided by sights and calculations using a computer, without the risk of human error or GPS spoofing. An automated celestial navigation system could either feed directly into the ship’s Inertial Navigation System (INS) or feed into a display in the pilothouse (with which a Navigator could verify the accuracy of active GPS inputs within a specified tolerance), both of which would provide redundancy to existing navigation systems. Automatic CELNAV systems are already used in the military, could be applied to surface ships rapidly, and could serve as a redundant, automated, and immediate aid to navigation against the potential threat of GPS signal disruption.

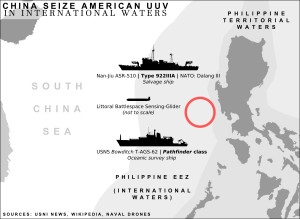

The Review Team’s recommendation to accelerate replacement of aging radars is a primary focus to support OODs, but given the capabilities of peer competitors against our GPS, rapid investment in shipboard CELNAV systems would be a worthwhile secondary objective. There is significant evidence of Russia testing a GPS spoofing capability in the Black Sea in June of this year, when more than twenty merchant ships’ Automated Identification Systems (AIS) were receiving locations placing them 25 nautical miles inland of Russia, near Gelendyhik Airport, rather than in the north-eastern portion of the Black Sea. Further, China maintains plans to actively combat the use of the Global Hawk UAV, to include, “electronic jamming of onboard spy equipment and aircraft-to-satellite signals used to remotely pilot the drones, [and] electronic disruption of GPS signals used for navigation.” At the outbreak of broader conflict one can imagine a far greater and more extensive denial effort for surface forces.

Due to potential threats, there are built-in securities for military GPS receivers to combat disruption threats. These include the Selective Availability Anti-Spoofing Module (SAASM) and expected upgrades for GPS Block III, to include more secure signal coding, with a scheduled inaugural launch in Spring 2018. Automated CELNAV can actively compliment both security mechanisms by providing redundancy against a technical failure or a cyber-attack and before the remaining GPS Block III satellites are brought online.

From a training perspective, the U.S. Navy reinstituted celestial navigation instruction for midshipmen in 2016 and quartermasters and junior officers in 2011 throughout their pipelines. The officers and quartermasters are trained to use the computer-based program STELLA (System To Estimate Latitude and Longitude Astronomically), developed by George Kaplan of the U.S. Naval Observatory in the 1990s. While the use of the program has sped the process of sightings to fixes from nearly an hour down to minutes, there is still a delay and the potential for human error. Automated CELNAV systems can provide both an extra layer of shipboard security against the potential threat of GPS disruption and assist in fixing the ship’s position continuously and as accurately as human navigators. Both arguments support increased readiness in the surface force and make ships more self-sufficient in the event of potential GPS disruption.

In 1999 George Kaplan argued that independent alternatives to GPS were necessary and required and that the hardware to implement these alternatives was readily available. Potential Automated CELNAV systems that could be configured for surface ships are already used in both the Navy and the Air Force. Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs), SR-71 Blackbird, RC-135, and the B-2 Bomber each use systems like the NAS-26, an astro-inertial system initially developed in the 1950s by Northrop for the Snark long-range cruise missile. Similar systems have previously been proposed for the Surface Forces. Cosmo Gator, an automated celestial navigation system, was submitted by LT William Hughes, then-Navigator of USS Benfold (DDG 65). This system would update the ship’s Inertial Navigation System (INS) with the calculated celestial position to provide essential navigation data for the rest of the combat system. OPNAV N4 funded LT Hughes’ proposal in March 2016 following the Innovation Jam event onboard USS Essex (LHD 2). Rapidly acquiring any of these various Automated CELNAV options supports the same piloting and situational awareness recommendations as an integrated bridge RADAR suite. The Navy can continue to cultivate a culture of improvement and further equip ships through the acquisition of more immediate aids to navigation like CELNAV systems.

Conclusion

As a result of the Comprehensive Review and associated ship investigations, the Surface Force is looking at innovative solutions to ensure that tragedies aren’t repeated. While the Navy strives to build a culture of improvement and to implement the CNO’s “High-Velocity Learning” concept continually, we must seek answers not only to the problems we face today but the threats we face tomorrow. The threats from peer competitors are defined and growing, but the options to provide greater shipboard redundancy are already created. In the same context that the Surface Force will endeavor to improve human systems integration for our bridge teams, we also should pursue Automated Celestial Navigation systems to make sure those same teams are never in doubt as to where they are in the first place.

Lieutenant (junior grade) Kyle Cregge is a U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer. He served on a destroyer and is a prospective Cruiser Division Officer. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or Department of Defense.

Featured Image: PHILIPPINE SEA (Sept. 3, 2016) Midshipman 2nd Class Benjamin Sam, a student at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, fixes the ship’s position using a sextant aboard the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Benfold (DDG 65). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Deven Leigh Ellis/Released)