By Peter Layton

When talking about current defence and security matters there seems strong agreement on at least one characteristic: the future is uncertain. Of course that’s true, and many things could potentially happen but, even so, what does this uncertainty mean for Defence?

Defence could choose a single future scenario, press on with it, and hope for the best. A fundamental problem in basing force development on a particular anticipated future is that if those specific circumstances don’t materialize, the force acquired might prove quite ineffective. This happened to Australia in the grim days of 1942. The inter-war emphasis on acquiring warships to be based in Singapore for coalition naval operations (PDF) proved completely inappropriate to the actual circumstances that arose. Precious time and resources were squandered preparing for an eventuality that didn’t happen, while consuming resources that could have created the force structure actually needed.

Defence could choose a single future scenario, press on with it, and hope for the best. A fundamental problem in basing force development on a particular anticipated future is that if those specific circumstances don’t materialize, the force acquired might prove quite ineffective. This happened to Australia in the grim days of 1942. The inter-war emphasis on acquiring warships to be based in Singapore for coalition naval operations (PDF) proved completely inappropriate to the actual circumstances that arose. Precious time and resources were squandered preparing for an eventuality that didn’t happen, while consuming resources that could have created the force structure actually needed.

This force structure dilemma, being ill-prepared for the future that actually occurs, is evident in the varying advice given about the implications of the rise of China. Some recommend building a bigger defence force ‘just in case,’ others opt for going amphibious (and in Japan as well), others say to engage while creating a force structure around hedging, yet others don’t see the need for worrying over a military response at all. These alternative courses reflect real uncertainty amongst professional analysts, defence staffs, foreign affairs specialists, and commentators over whether China’s rise will be peaceful or not—and what the appropriate response is if not. It seems that realists fear that war’s inevitable while liberal thinkers see much value in deep economic integration with the People’s Republic. The real answer is that no one yet knows; there are many possible futures, depending on the choices that China and the rest of us make.

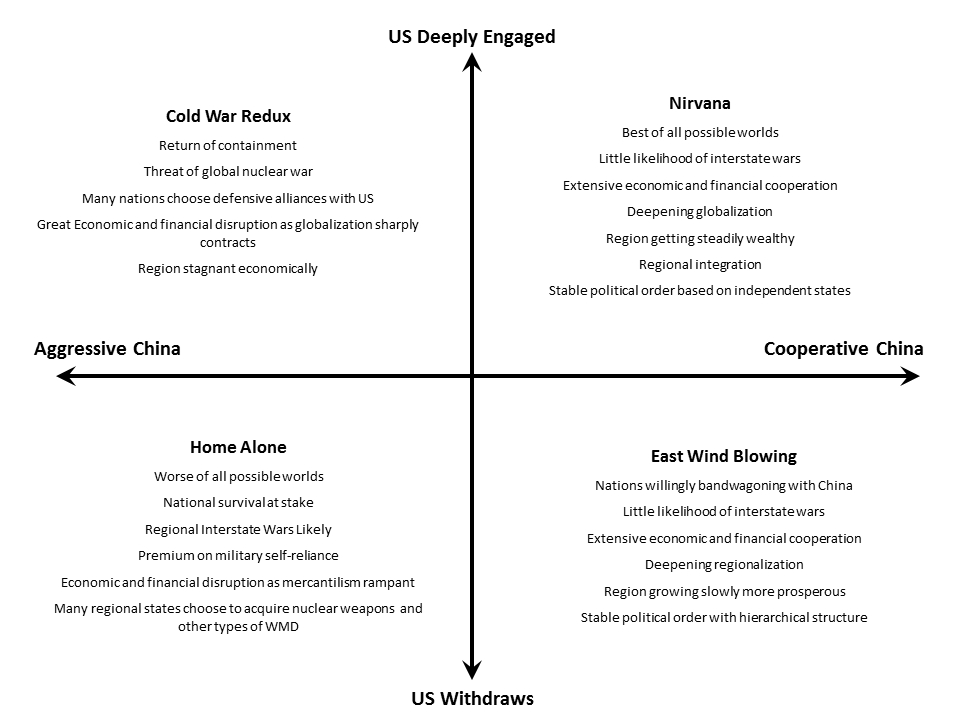

One way of thinking about this is to accept this uncertainty and survey the space of possibilities (with credit to LTG Noboru Yamaguchi for pointing this out). To take extreme positions, China will become either a peaceful great power cooperating with all or a revisionist great power aggressively remaking Asia. In either circumstance the role of the United States will be highly influential in determining what Australia and many others will do. America could remain deeply engaged in the Asian region and be strongly intent on shaping the regional order. Conversely, it might retire from the field of play and focus its efforts elsewhere. What do these four alternative futures look like for us? Maybe like this (click to enlarge):

Seen this way, most futures seem OK. Three range from the really good ‘Nirvana’ to the ‘we’ve done this before and survived’ Cold War Redux. The Home Alone future is, however, a really bad one. Should we then accept this worst-case analysis and structure our defence force for it? If we did, then surely the worst that could happen is that Australia will be unnecessarily poorer than it should be? Not quite. The danger of going that route is that others might follow—they might think we know something they don’t or that we harbour aggressive intentions ourselves. For example, developing a nuclear capability would certainly draw attention.

How about force structuring around the competition-heavy Cold War Redux possibility? Such a force would be in case an aggressive China arose and the U.S. embraced a new containment strategy that we’d become a part of. If we really thought such a future was likely, then extensive trade with the ‘enemy’ would be most unwise as this would simply be supporting a hostile military build-up—a notion that might have historical resonance as well. Sharply constraining trade though would inflict some real economic damage on us as we missed out on much of the financial gains from China’s rise. Worse, it might also set off a security dilemma in which China sees the west bulking up its power projection and containment capabilities and talks itself into a major arms expansion. We need to be careful that we don’t inadvertently create the future we fear.

Should we then hope for the best and force structure for the better alternatives? This though runs significant risks if the future turns dark, as it did with the Japanese attacks in late 1942.

A potential answer lies in adopting a robust force-development strategy that aims to meet the different challenges of the four possible worlds, identified with all their differences, albeit set against the constraints of limited resources. Such a strategy doesn’t presuppose an ability to identify the most, or indeed the least, likely outcomes. Instead, it seeks to build a force structure that resembles a market, with a range of capabilities that covers a broad array of possibilities and evolves over time, with some succeeding and some failing. In this approach, a robust strategy isn’t an ‘optimum’ strategy, this being inherently impossible in an uncertain environment (except in retrospect). Instead, it tries to meet strategic needs within a limited resource base by being designed to evolve over time as strategic circumstances change.

There are of course some problems with this approach. It needs some real intellectual thought—always a scarce commodity—and it isn’t ‘set and forget’. The external environment needs continuous monitoring so that the force structure can be steadily tweaked as the actual future progressively arrives.

There are of course some problems with this approach. It needs some real intellectual thought—always a scarce commodity—and it isn’t ‘set and forget’. The external environment needs continuous monitoring so that the force structure can be steadily tweaked as the actual future progressively arrives.

The value of the approach lies in realising that the future could be good or downright terrible, but that we might be able to tilt the probabilities towards the better futures. In using our instruments of national power and in building a force structure we can act to nudge the future in the direction we prefer. With an understanding of what might happen, we’re better able to work towards achieving such an outcome.

With such an optimistic thought comes a word of warning. While this focus has been on China, security even in the Nirvana future might well include dealing with tyrannical regimes, failing states, transnational terrorism and civil wars. There’ll be a need for effective and efficient armed forces in whichever alternative future arrives, it’s just their shape that will differ—and whether we’re prepared or not.

Peter Layton is undertaking a research PhD in grand strategy at UNSW, and has been an associate professor of national security strategy at the US National Defense University.

This post first appeared at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (APSI)’s blog The Strategist.