By Lieutenant Judith Hee Rooney, USN

Introduction

As the United States shifts focus from the Global War on Terror to peer competitors, senior naval leaders have increased messaging to the fleet that focuses on preparing for war at sea. Considering this shift, I investigated the state of the warfighter mentality in the Surface Warfare Officer (SWO) community to gauge how the community felt about its own readiness as part of my program at the Naval Postgraduate School. Although the Navy gauges readiness in many ways, my goal was to go directly to the source by interviewing members of the SWO community – while avoiding the constraints and endemic fatigue so common in survey methodology. I used semi-structured interviews to identify attitudes, opinions, and trends related to the warfighter mentality across the ranks of O-2 to O-6. I conducted 23 interviews with volunteer subjects, each lasting one to three hours. Participants in this research study came from different commands and their tactical and operational experiences varied widely.

Given the current maritime stakes, understanding the fleet’s mental, tactical, and realistic state of readiness, and identifying the strengths and weaknesses in how we are preparing our warfighters is of utmost importance and was expressed passionately in every single interview conducted. Seven common themes about the warfighter mentality emerged from these interviews.

What Does the Term “Warfighter” Mean?

The survey participants shared a common framework and understanding of the characteristics of an ideal “warfighter.” Traits such as “tactical proficiency,” “sound and timely decision making,” “calm under pressure,” “physically and mentally fit,” “confident,” “competent,” and “leader” were all used to describe and define a good warfighter. However, my research suggests that the culture of the SWO community works against developing these characteristics more than it develops them. The approach to developing the warfighter mentality in the community was described as overly passive, with little to no direct or active efforts outside of entry-level indoctrination and training. As a result, rather than focusing on warfighter development, interviewees described how a “workaholic” mentality that was prioritized instead. Officers who are afraid to fail or make mistakes, micromanage, are erosively competitive, perpetuate the “zero-defect” mentality, and/or play wardroom politics were identified as the major hinderances to community warfighter development.

Another important indicator of the state of the warfighter mentality is the level of trust that SWOs have for one another. My research suggests that there is much more distrust and cynicism in the lower ranking officers than among senior officers. The majority of junior officers (O-2 to O-4) said that they, if given the option, would only follow about 5-10% of all the SWOs they knew into combat with no reservations. Several of them could only think of one or two officers total, who they would follow without reservation. Trust improved significantly with seniority, especially at the O-6 level, where the majority said that they would follow 60–90% of all the SWOs they knew.

On the other hand, the level of dedication SWOs have to their work was identified as a positive aspect of the community and seen to bolster warfighter development. As one SWO put it, “there is a lot of goodness on the waterfront.” SWOs are dedicated to their work and want to ensure that their ships and sailors succeed. Homing in, exploiting the best parts of the community, and shifting focus to operational readiness, as the system was intended, can create confident, competent, and able crews to deploy and achieve mission success in combat. “SWOs are driven, they are proven, they understand endurance, perseverance. They are multitaskers, they can prioritize. They are leaders.” One O-6 believed that “SWOs are the hardest on SWOs. We are very hard on ourselves. There are a lot of great people in the community. If we took the time to recognize the good work that we do, we’d be a lot better off.”

Difference in Perception of Fleet Ability

My research revealed a positive link between rank and optimism regarding the Navy’s readiness to fight and win a war at sea. Senior officers in the grades of O-5 and O-6 were more optimistic about the fleet’s readiness and had more confidence that their ships, shipmates, and selves would endure combat and be successful. Conversely, junior officers had little faith in the same. At the junior levels, most admitted to not seriously thinking about preparing for a kinetic fight. For example, they reasoned that “the surface fleet had not seen real combat in a very long time,” while others were more worried about the day-to-day functions of their jobs that were unrelated to preparing for the realities of combat. However, several officers displayed a conscious and active interest in developing their warfighter mentality, warrior toughness, capabilities, or edge, attributing it to be a product of an internal drive.

It is important to note that the strongest of these convictions came from SWOs who were originally interested in serving in a different community (particularly the Naval Special Warfare community), had seen or experienced life-threatening situations, or were O-5s. In general, however, SWOs do not believe that the fleet is ready for a kinetic fight at sea. Most believed that, in the event of kinetic action, it would be an occasion to rise to; with some stepping up and leading the charge, some needing leadership and direction, and some being rendered completely useless. “The exception [wouldn’t] be those who are extremely willing, able, and capable. The exception [would] be those who aren’t.” Much of this stemmed from the way SWOs feel they are preparing themselves and being prepared by “Big Navy.” One O-6 stated that “at the O-5/O-6 level, SWOs are working hard to ready their ships and crews for battle. However, we are working under a structure that is not supportive of the end goal.” Most interviewees did not believe they were trained for the realities of combat, whether in tactics, guile, versatile skills, or bloodshed. It should also be noted that very few SWOs have ever seen combat, and even fewer have seen combat at sea.

Every SWO interviewed experienced at least one mishap or near-mishap while serving on a ship; most of them being near-miss, close quarters situations due to negligence, complacency, training deficiencies, or confusion. While some SWOs expressed that they remained calm and controlled throughout their situations, others admitted to feeling flustered or panicked alongside their watch teams, some instances to include the CO or XO. Several officers also expressed that the pressure of performing sometimes led to putting the ship and crew in precarious situations, even when it was not mission critical or time sensitive.

Not All SWOs Are Created Equal

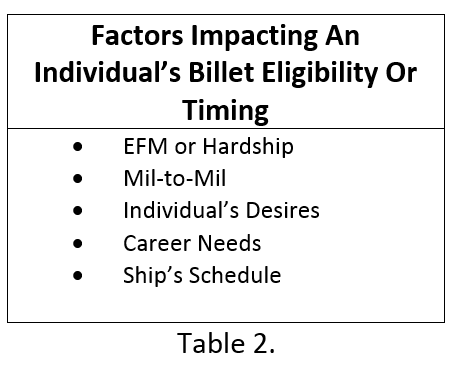

The professional development of SWOs seems to largely depend on a few random factors. A lack of mentorship was identified as one of the biggest challenges they face, as it seems to be dependent on being in the “right place” at the “right time.” Mentorship was also described to have to be individually sought out up and down the chain of command, suggesting that commands do little to foster mentor-mentee relationships.

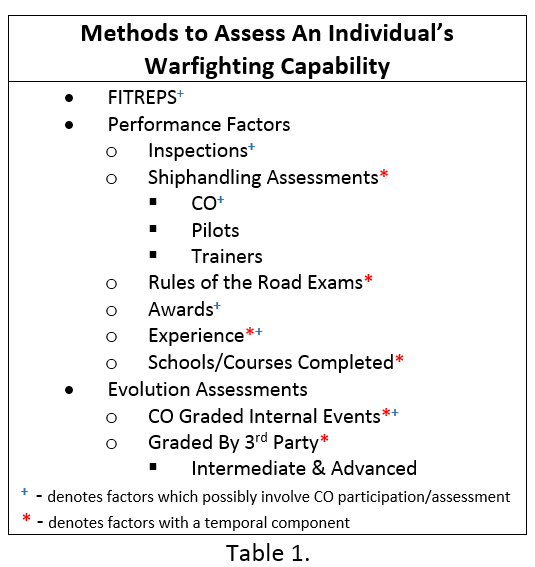

Another major challenge identified was the varied standards of qualifications. According to interviewees, there is no real standardization when it comes to training or major qualifications, such as OOD, SWO, EOOW, or TAO. While the PQS system exists, the rigor and standards of qualifications are set at the command level, meaning that the quality of qualifications and professional development are fully dependent on the standards set by the ship’s CO. As a result, officers are developing differently across the fleet, sometimes even within the same wardrooms. Several interviewees expressed concern about “give me” qualifications awarded by their previous COs despite them not being proficient, capable, or knowledgeable enough to “sit the seat.” This approach to professional development helped to “degrad[e] warfighting because it makes being a SWO mean less.”

Lastly, onboard training and drills were seen to differ by experience and priorities. Some interviewees described trainings and drills to be taken seriously and felt that they were effective. However, the majority had contrary views on how their ships conducted trainings and drills, even if that meant sending ships on deployment ill prepared after cutting corners. In their experiences, training and drills were done more so to be able to say a requirement was met (e.g., “check in the box”) rather than to prepare crews for operational employment; some went as far as to describe them as “rehearsals” for inspections and assessments. Most training scenarios were described to be “unrealistic, poorly constructed, and a series of people going through the motions.” One officer believed that “people don’t take it seriously because they don’t truly think that something like this is going to happen.” Another stated that “it’s better to be a warrior in a garden than a gardener in a war, and right now, we are just a bunch of gardeners.”

When questioned why the fleet’s approach to training lacked focus, interviewees across the board believed that there were too many aspects of the job that took away or distracted from effective warfighter development. Administrative requirements, a “zero-defect” mentality, flaws in the maintenance system, unforgiving ship schedules, and deployment rotations were just a few examples. The combination of these distractions was seen to result in ships and crews deploying without the necessary skills to win in a kinetic fight. Many SWOs, including ship captains, expressed that ships are being sent out “administratively ready” but that deployments were the ideal time to conduct actual “effective and realistic training” as there is no pressure from outside entities or competing priorities. Conceptually, however, the ship and crew should already be at their peak capability prior to going on deployment.

SWOs across the board would like to see better and more effective training onboard ships at all stages of the training cycle. They recognized deficiencies the system and believed that improvements in training would make the biggest difference in proper system execution and warfighter mentality development. They believed that the structure of the cycle, the “crawl, walk, run” approach to surface warfare, had a lot of potential to be effective and made sense. However, the execution of this system was widely criticized. SWOs want to see changes to reflect and support realistic, relevant, and serious training met with a motivated and bought-in crew. Departing from the “check in the box” approach could be the most influential shift for warfighter development in the fleet

The Ethics of Readiness

Several officers shared that they, or others close to them, acted unethically in response to external pressures when reporting readiness levels. Even for major certifications like COMPTUEX, both assessors and participants alike described that certain parts of scenarios were sometimes modified to give ships the “green light to deploy.” Due to the overwhelming and compressed training cycle, constant turnover, and undermanned crews, ships are being forced to complete integral training and development at faster rates, making it difficult for SWOs to manage every program simultaneously successfully and effectively. Additionally, the “get it done attitude” was described to be detrimental because “it doesn’t seem like ‘Big Navy’ cares about how we get it done. They just want it done and a green spreadsheet…this leads to people cutting corners and presenting a false state of readiness to higher ups just to make them happy and to make themselves look like good leaders.”

Interviewees expressed a sense that there was very little room to fail without creating more pain and suffering for the crew; some ships were unable to send their sailors home before deploying for seven to nine months as a result from failure. Therefore, meeting requirements, keeping up with the ship’s operational tempo, and doing it all “in the green” were all sources of stress felt by SWOs, contributing to the “zero-defect” mentality, and, in some cases, unethical behavior.

SWOs Endure Extreme Stress About the Same Things

SWOs across ranks believe that their job-induced stress comes from the same things. Almost every interviewee expressed that they put an immense amount of pressure on themselves to succeed. As many SWOs are described to have “type-A” personalities, having control over their work is comforting. Throughout the interviews, officers often referred to “the grind never stops” mentality and the perpetuated “get it done” attitude. These mindsets have existed in the SWO community through decades of experience, budget cuts, optimization plans, support for landlocked wars, maintenance backlogs, etc. They feel that this pressure, in addition to the tight deployment work up schedule, creates “high stakes” for ship captains and their crews to complete evolutions, drills, assessments, and certifications without fail. Many SWOs feel like they are constantly “burning the candle at both ends.”

Fear of failure seems to contribute to the risk averse culture in the SWO community, which was highlighted as an aspect that degrades the community overall. SWOs expressed a fear of making mistakes as they believed it would negatively affect their career projection. Whether it was a junior officer with aspirations of commanding a warship, a department head close to retirement, or a ship captain eyeing major command or a star, they believe that one mistake or a single bad fitness report could derail their entire careers. According to the officers interviewed, this fear results in the timidity, hesitancy, and micromanagement seen across the community. Not only did they feel that their careers were on the line by their own actions, decisions, and judgments, but by those of their subordinates as well. This kind of pressure was seen to keep SWOs on edge, toxically competitive, and risk averse. While taking the slow, smooth, methodical, and careful approach to operations have kept most SWOs out of shallow waters, it has also left many wondering if they would be able to exercise the grit, toughness, and quick thinking required in times of extremis and threat.

Attraction to the SWO Community

The majority of SWOs interviewed did not originally want to be SWOs, although there were a few distinguishable factors about being a SWO most believed to be favorable. Because SWOs start their service obligation almost immediately, they “hit the fleet” faster than any other community. Unlike pilots, submariners, special warfare operators, and Marines, who go through lengthy training pipelines before entering the fleet, the SWO community traditionally sends their officers straight to ships to begin on-the-job training. Almost every interviewee liked the idea of getting to the fleet sooner. Whether they wanted to start repaying their service obligation right away, set the conditions to laterally transfer to a different community, or bypass lengthy and rigorous training commands, the notion of apprenticing in a job coupled with working with sailors was appreciated by all. Being given the opportunity to lead sailors sooner was particularly appealing and there was a significant theme of servant leadership across ranks. Specifically, a common motivation within the SWO community is to serve and work for the betterment of their subordinates, even when times are tough. This approach to leadership is extremely apparent at the junior officer level.

Mental Fitness is a Priority, Physical Fitness is Not

Physical fitness was seen to be one of the easiest things to ignore when other requirements emerged. Other aspects of the job were often seen to prioritize above physical health, although most officers interviewed believed it to be an integral aspect of warfighting. Not only does physical fitness give one the strength and stamina to run up and down ladder wells, drag shipmates to safety, hold one’s breath under water, fight fires, or stand a watch at General Quarters for hours on end, it also gives you mental clarity, a relief in stressful times, and an opportunity to push yourself past your comfort zone. Yet, outside of “PRT season” when the Navy conducts physical fitness assessments, physical fitness is not a priority for SWOs. One officer stated that “the state of the fleet in physical fitness shows how much we prioritize the warfare part of surface warfare.” However, some commands were described to have tried to prioritize physical fitness when they could. Those command were subsequently described to have had leadership who were physically fit themselves and who prioritized physical fitness on a personal level.

Conversely, mental fitness was seen to have made strides. The stigma associated with seeking help for mental health has lessened in recent years. With that, the message of taking care of yourself, along with the availability of programs and resources, have become more prevalent. Mental health was generally taken seriously at all levels of the chain of command. However, the attention on mental fitness was believed to be very reactionary. Interviewees believed that there was little to no emphasis put on preventative maintenance or proactively developing mental toughness, fitness, or health. Actively working on mental toughness and cognitive development was identified as another way to bolster the warfighter mentality.

Conclusion

My research indicated that the SWO community could benefit from putting more emphasis on actively developing the warfighter mentality among both junior and senior officers. In my thesis, I make several recommendations for how the community can do this. One of them is to publish doctrine that includes SWO warfighter behavioral and cognitive characteristics. Neither I, nor anyone I interviewed, could recall or locate official Navy doctrine, publication, or manual that explicitly describes the values and characteristics of a warfighter as it pertains to the SWO community, nor how to nurture and develop them.

It is important to standardize the vision for who the Navy wants the average SWO to be as far as leadership and warfighting. Publishing and disseminating the key warfighting tenants that the community values can help directing SWOs in the same direction and focusing commanders and wardrooms in cultivating the SWO warfighter as well as the warfighter mentality as the community intends. Another recommendation is to standardize the qualification process in the SWO community. This would ensure that each SWO is being trained and assessed by the same rigorous standards across the fleet at all levels. While on the job training is an integral part of experience and practical knowledge, the difference in the quality of training throughout the fleet was apparent, particularly when considering one’s duty stations, coasts, or countries.

The SWO community has historically been seen as a “catch all” community as it seemingly does not require great skill or aptitude to join the community. There does not seem to be as much prestige or allure in comparison to other communities. Those who fail out of other programs like flight school or nuclear school end up redesignating as SWOs, creating the perception of “those who can’t… become SWOs.” As much as the Navy has tried to revitalize the community’s reputation, it is not as desirable as other communities with higher standards. Creating a rigorous training pipeline to include shipboard watch station qualifications would not only help rehabilitate the community’s reputation, but it would also raise the baseline level of knowledge of the SWO community, delivering ready and capable officers who are ready to contribute to the team the moment they step on their ships.

The divide between the perception and the assessment of readiness amongst the different ranks of the SWO community is particularly interesting as they all serve in the same Navy, on the same ships, and, when the time comes, will inevitably go into battle together. The mentality of wanting to do good work, doing it right the first time, every time, and having high expectations speaks highly to the thoroughness and dedication of SWOs in general. These are qualities, if shaped and aimed in the right direction, can do more help than harm in the community. Focusing on operational development, quality training, and incorporating the “why” in everything that they do can bring SWOs that much closer to the fight and ultimately closer to triumphantly demonstrating naval superiority against any threat across the globe.

LT Judith Hee Rooney is a Human Resources officer currently serving as the Enlisted Programs Officer for Naval Talent Acquisitions Group New England. Previously, LT Rooney served as a SWO onboard USS KEARSARGE (LHD-3) as the Damage Control Division Officer and the Internal Communications Officer and onboard USS WINSTON S. CHURCHILL (DDG-81) as the Assistant Chief Engineer. She got her Master of Science in Manpower Systems Analysis from the Naval Postgraduate School where she won the Surface Navy Association’s Award for Excellence in Surface Warfare Research for her thesis: The State of the Warfighter Mentality in the SWO Community.

Featured Image: The U.S. Navy Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS John Finn (DDG-113) arrives at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii (USA), on 10 July 2017, in preparation for its commissioning ceremony. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)